Crickets as pets

Keeping crickets as pets emerged in China in early antiquity. Initially, crickets were kept for their "songs" (stridulation). In the early 12th century the Chinese people began holding cricket fights.[note 1] Throughout the Imperial era the Chinese also kept pet cicadas and grasshoppers, but crickets were the favorites in the Forbidden City and with the commoners alike. The art of selecting and breeding the finest fighting crickets was perfected during the Qing dynasty and remained a monopoly of the imperial court until the beginning of the 19th century.

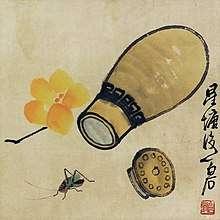

The Imperial patronage promoted the art of making elaborate cricket containers and individual cricket homes. Traditional Chinese cricket homes come in three distinct shapes: wooden cages, ceramic jars, and gourds. Cages are used primarily for trapping and transportation. Gourds and ceramic jars are used as permanent cricket homes in winter and summer, respectively. They are treated with special mortar to enhance the apparent loudness and tone of a cricket's song. The imperial gardeners grew custom-shaped molded gourds tailored to each species of cricket. Their trade secrets were lost during the Chinese Civil War and the Cultural Revolution, but crickets remain a favorite pet of the Chinese to the present day. The Japanese pet cricket culture, which emerged at least a thousand years ago, has practically vanished during the 20th century.

Chinese cricket culture and cricket-related business is highly seasonal. Trapping crickets in the fields peaks in August and extends into September. The crickets soon end up at the markets of Shanghai and other major cities. Cricket fighting season extends until the end of autumn, overlapping with the Mid-Autumn Festival and the National Day. Chinese breeders are striving to make cricket fighting a year-round pastime, but the seasonal tradition prevails.

Modern Western sources recommend keeping pet crickets in transparent jars or small terrariums providing at least two inches of soil for burrowing and containing egg-crate shells or similar objects for shelter.[1] A cricket's life span is short: Development from an egg to imago takes from one to two months. The imago then lives for around one month. Cricket hobbyists have to frequently replace aging insects with younger ones which are either specifically bred for cricket fighting or caught in the wild. This makes crickets less appealing as pets in Western countries. The speed of growth, coupled with the ease of breeding and raising larvae, makes industrial-grown crickets a preferred and inexpensive food source for pet birds, reptiles, and spiders.

Cricket biology

pennsylvanicus

True crickets are insects of the Gryllidae, a cosmopolitan family of around 100 genera comprising some 800 species, belonging to the order Orthoptera.[2] Crickets, like other Orthoptera (grasshoppers and katydids), are capable of producing high-pitched sound by stridulation. Crickets differ from other Orthoptera in four aspects: Crickets possess three-segmented tarsi and long antennae; their tympanum is located at the base of the front tibia; and the females have long, slender ovipositors.[3]

The life cycle of a cricket usually spans no more than three months. The larvae of the field cricket hatch from eggs in 7–8 days, while those of Acheta domesticus develop in 11–12 days. Development of the larvae in a controlled, warm (30 °C (86 °F)) farm environment takes four to five weeks for all cultivated species.[4] After the fourth or fifth larval instar the wingless larvae moult into the winged imago which lives for around one month.[5] Crickets are omnivorous, opportunistic scavengers. They feed on decaying vegetable matter and fruit, and attack weaker insects or their larvae.[note 2]

A male cricket "sings" by raising his wing covers (tegmina) above the body and rubbing their bases against each other. The wing covers of a mature male cricket have protruding, irregularly shaped veins.[6] The scraper of the left wing cover rubs against the file of the right wing, producing a high-pitched chirp.[7] Crickets are much smaller than the sound wavelengths that they emit, which makes them inefficient transducers, but they overcome this disadvantage by using external natural resonators. Ground-dwelling field crickets use their funnel-shaped burrow entrances as acoustic horns; Oecanthus burmeisteri attach themselves to leaves which serve as soundboards and increase sound volume by 15 to 47 times.[8] Chinese handlers increase the apparent loudness of their captive crickets by waxing the insects' tympanum with a mixture of cypress or lacebark pine tree sap and cinnabar. A legend says that this treatment was discovered in the day of the Qing Dynasty, when the Emperor's cricket, held in a cage suspended from a pine tree, was observed to develop an "unusually beautiful voice" after accidentally dipping its wings in tree sap.[9]

Entomologists from Ivan Regen onward have agreed that the principal purpose of a male cricket's "song" is to attract females for mating.[10] Berthold Laufer and Frank Lutz recognized the fact but noted that it was not clear why males do it continuously throughout most of their adult lives, when actual mating doesn't take much time.[11] More is known about the attractive mechanism of a cricket's song. Scientists exposed cricket females to synthesized "cricket songs", carefully varying different acoustic parameters, and measured the degree of females' response to different sounds. They found that although each species has its own optimal mating call, the repetition rate of chirp "syllables" was the single most important parameter.[12] A male's singing skills do not guarantee him instant success: other, silent, males may be waiting nearby to intercept the females he attracts.[13] Other males may be attracted by the song and rush to the singer just as females do. When another cricket confronts a singing male, the two insects determine each other's sex by touching their antennae. If it turns out that both crickets are male, the contact leads to a fight.[14][note 3] Crickets, and Orthoptera in general, are model organisms for the study of male-male aggression, although females can also be aggressive.[15] According to Judge and Bonanno, the shape and size of male crickets' heads are a direct result of selection through male-male fights.[16]

The fact that only males sing, and only males fight, means that females have little value as pets apart from breeding. Chinese keepers feed young home-bred females to birds as soon as crickets display sexual dimorphism.[17] There is one notable exception: males of Homoeogryllus japonicus (suzumushi or jin zhong) sing only in the presence of females, so some females are spared to provide company to the males.[17]

Pet crickets in China

History

The singing cricket became a domestic pet in early antiquity.[18] The ancestors of modern Chinese people possessed a unique attitude towards small creatures, which is preserved in present-day culture of flower, bird, fish, insect.[note 4] Other cultures studied and conquered big game: large animals, birds, and fishes. The Chinese, according to Laufer, were more interested in insects than in all other wildlife. Insects, rather than mammals or birds, became symbols of bravery (mantis) or resurrection (cicada), and became a precious economic asset (silkworm).[19]

Between 500 and 200 B.C. the Chinese compiled Erya, a universal encyclopedia which prominently featured insects.[20] The Affairs of the period Tsin-Tao (742–756) mention that "whenever the autumnal season arrives, the ladies of the palace catch crickets in small golden cages ... and during the night hearken to the voices of the insects. This custom was imitated by all the people."[21] The oldest artifact identified as a cricket home was discovered in a tomb dated 960 A.D.[22] The Field Museum of Natural History owned a 12th-century scroll painted by Su Han-Chen depicting children playing with crickets. By this time, as evidenced in the painting, the Chinese had already developed the art of making clay cricket homes, the skills of careful handling of the insects, and the practice of tickling to stimulate them.[23] The first reliable accounts of cricket fights date back to the 12th century (Song dynasty) but there is also a theory tracing cricket fights to the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (8th century).[24]

Singing and fighting crickets were the favorite pets of the Emperors of China. The noble pastime attracted the educated class, resulting in a wealth of medieval treatises on keeping crickets. The oldest one, The Book of Crickets (Tsu chi king), was written by Kia Se-Tao in the first half of the 13th century. It was followed by the Ming period books by Chou Li-Tsin and Liu Tong and early Qing period books by Fang Hu and Chen Hao-Tse.[25] According to Yutaka Suga, cricket fighting was also popular among the commoners of Beijing and they, rather than the nobles, were "the driving force behind the amusement" during the Qing period.[24] The court, in turn, forced the commoners to collect and pay their dues in fine fighting crickets, as was retold by Pu Songling in A Cricket Boy (early 18th century). In this story, which is set in the reign of the Xuande Emperor, an unfortunate peasant was given the impossible task of finding the strongest prize-fighting cricket. His cricket miraculously defeated all Emperor's insects; the ending reveals that the champion was mysteriously guided by the spirit of his own unconscious child.[26]

One aspect of cricket-keeping, that of growing molded, custom-shaped gourds destined to become cricket homes, was an exclusive monopoly of the Forbidden City. The royal gardeners would place the ovary of an emerging Lagenaria fruit inside an earthen mould, forcing the fruit to take up the desired shape. The oldest surviving molded gourd, Hasshin Hyōko dated 1238, is preserved in Hōryū-ji temple in Japan. The art reached its peak in the 18th century, when the gardeners implemented reusable carved wood and disposable clay molds. The shapes of the gourds were tailored to different species of cricket: larger gourds for larger species, long-bottle gourds for the species known for long hops, and so on. Immature fruit easily reproduces the artwork carved into the mold, but also easily picks up any natural or man-made impurities. The finest craftsmen exploited, rather than concealed, these blemishes. Molded gourds were a symbol of the highest social standing. The ones held by Chinese royalty depicted in medieval portraits were actually prized cricket containers.[27] The Yongzheng Emperor held a gourd in his hand even when he was sleeping, the Qianlong Emperor maintained a private molded gourd garden. In the 1800s the Jiaqing Emperor lifted the monopoly on molded gourds, but they remained expensive even for the upper classes.[28]

At the end of the Imperial era Empress Dowager Cixi revitalized cricket fighting by staging contests between cricket breeders.[29] A cricket of her successor, the infant Emperor Puyi, became a plot device in Bernardo Bertolucci's film The Last Emperor (1987). Bertolucci presented the cricket's container as a magic black box that opens up the memories of Puyi. According to Bruce Sklarew, the cricket, mysteriously emerging from the box, carries at least three meanings: it is the metaphor of Puyi himself, it is the metaphor of his wisdom acquired through suffering, and a symbol of the ultimate freedom that comes with death.[30]

The ancient secrets of cricket handling and cricket-related crafts, only some of which were recorded on paper, were largely lost during the Chinese Civil War. From 1949 to 1976[31] the Communist regime suppressed cricket keeping, which was deemed an unacceptable distraction and a symbol of the past. Cricket trade was banned altogether in the 1950s, but continued secretly even on the People's Square of Shanghai.[32] A dozen illegal markets emerged in the 1980s, and in 1987 the government formally allowed trading crickets on the Liuhe Road. By 1993 there were five legal markets,[32] and in the 21st century Shanghai has over 20 cricket markets.

Trapping

The short life span of a cricket necessitates frequent replacement of aging insects. The crickets sold in present-day China are usually caught in the wild in remote provinces. Earlier, most crickets sold in major cities were caught in the nearby countryside, but in the 21st century a local catch, or dichong, is extremely rare.[33] The majority of crickets sold in Shanghai in the 1990s and the 2000s came from rural Ningjin County in Shandong, where cricket hunting became a second job for local peasants.[34] Practically all people of Ningjin—men and women of all ages—engage in the cricket business.[33] A peasant usually makes around 70 yuan per night, and 2000 yuan per season.[35] A very good season can bring a family over 10,000 yuan ($1,210).[36]

Cricket catching extends over August and September. Crickets are most active between midnight and dawn.[24] They are agile creatures, and when distressed they quickly hide into burrows or improvised shelter, or hop and even fly away.[37] Typical Chinese crickets hide underground,[note 5] so the catcher's first task is to either force or lure the insect out of its hideout. Trappers from the North of China use lighted candles to lure insects into their traps. Trappers from the South use iron cage-like lanterns or fire baskets to carry smoldering charcoal which forces insects to flee from the smoke. Other ways of forcing the insect out involve flooding their burrows or setting up juicy fruit baits.[38] The Ningjin trappers use a simple tool, similar to an ice pick, for digging earth and poking under stones.[39]

The trapper who has located a cricket must catch and contain the insect without causing it any injuries. Present-day trappers use zhao, a soft catching net on a wire frame, to contain the cricket on the ground. The captured crickets are then placed into a clay pot and stay there until being sold; they are fed a few boiled rice grains per day.[40] Earlier, the Chinese used cage-like traps made of bamboo or ivory rods.[38] Pavel Piassetsky, who visited Beijing in the 1880s, described a different technique. The Beijing people used two kind of tools: a bell-like bowl with a hole in its bottom, and a tube several inches long. When a cricket was forced to leave its hideout, the trapper would quickly cover it with the bell. When the trapped cricket emerged from the hole, the trapper would present the tube, and the cricket would eagerly hide inside it. The plugged tube then became a convenient cricket cage.[41]

Logistics

In his 1927 book, Laufer described seven species of crickets kept by the people of Beijing; Oecanthus rufescens and Homeogryllys japonicus were the favorites based on their "singing" rather than fighting qualities.[42] The most common species sold by Chinese traders in the 21st century are Anaxipha pallidula, Homeoxipha lycoides, Gryllus bimaculatus.[43] Velarifictorus micado from Shandong is especially prized.[44] Ningjin peasants collect only the Velarifictorus species and discard the abundant Teleogryllus emma and Loxoblemmus doenitzii, which are not used in cricket fighting.[45] Peasants usually cannot even remotely estimate the probable market value of the catch. At best, they can sort crickets by size; their objective is to sell the catch to the wholesalers as soon as possible.[46] They offload their catch at the local roadside markets (daji) in the early morning, immediately after the night shift. They frequently overstate their selling skills: many crickets remain unsold and are discarded.[35]

The trade is driven by urban consumers.[32] As recently as 1991, from 300,000 to 400,000 people of Shanghai engaged in cricket fighting, with around 100,000 crickets fighting every day of the August–September season.[31] Dealers from a large city normally control cricket haunts within 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) of their base.[32] The dealers and aficionados from Shanghai arrive in Ningjin in groups and lodge in the villages. Unlike the peasants, they are skilled in quick evaluation of the insects and have a stronger hand in bargaining.[47] They have complex systems of ranking crickets in up to 140 grades (pinzhong).[48] They quickly get what they came for and return to their home cities. The markets that normally sell bonsai and goldfish are suddenly overwhelmed with a mass of cricket buyers and sellers.[32] Shanghai is a clear leader but the same activity takes place in all major cities.[32] Local authorities encourage the trade and organize seasonal cricket fairs.[49]

Fighting and gambling

Cricket fighting is a seasonal sport, "an autumn pastime" (qiu xing) that relies on the supply of wild-caught insects.[44] Young crickets must mature before fighting; thus the high season begins near the autumn equinox.[50] Crickets are placed in individual clay homes sprinkled with herbal medicines, bathed in licorice infusion every three to five days and fed according to each owner's secret recipes.[51] The traditional diet of captive crickets, described by Laufer, consisted of seasonal green vegetables in the summer and masticated chestnuts and yellow beans in winter. The Southern Chinese also fed their crickets chopped fish, insects and honey. Fighting crickets were given a special treatment of rice, lotus seeds, and mosquitoes, and an undisclosed herbal stimulant.[52]

The owners closely watch the cricket's behavior for signs of discomfort, and adjust the diet to bring the fighters into shape.[53] The crickets are mated with females before the fight, as the Chinese believe that, unlike other beings, male crickets become more aggressive after having sex.[50] In Laufer's time the fighters were sorted in three weight classes; present-day Shanghai aficionados have a system of nine classes from 0.51 to 0.74 grams. Both sides in a fight should belong to the same class, thus before the fight the crickets are weighed on high-precision scales (huang). The units of cricket weight, zun and dian, are not used anywhere else.[54]

The fights are held outdoors[55] in an oval ring (douzha),[54] which was traditionally a flat clay pot but is more commonly a plastic container today. Crickets are stimulated with a tickler (cao) made of a rat's whisker hairs (Beijing style) or of fresh grass strands (Shanghai style).[56] The handler tickles the cricket's head, then the abdomen, and finally the hind legs.[57] Each fight consists of three or five bouts; the winner must score in two of three or three of five bouts. A bout is stopped when the triumphant winner extends his wings as a sign of victory, or when his opponent flees from the action.[58] Laufer wrote that the fights of his time usually ended in the death of one of the crickets: The winners physically beheaded their opponents.[57] Present-day fights may look vicious but are not lethal; the loser is always allowed to flee from the winner.[44]

A winning cricket progresses from fight to fight to the rank of "the General". Laufer wrote that the people of Whampoa buried their dead fighting champions in tiny silver coffins. According to a local tradition, a proper burial of a "general" ensures a good catch of wild crickets.[59] Live champion fighters sell for hundreds, rarely thousands of U.S. dollars.[44] The highest price for a single cricket was recorded in 1999 at 100,000 yuan ($12,000).[36] The lowest price, of around 1 yuan, is for the mute and shy females that still have some value as consorts to the fighting males. The cheapest males sell for five yuan.[36]

Betting on cricket fights is outlawed throughout the PRC but widespread on the streets. In 2004 Shanghai police reported that it had raided 17,478 gambling places involving around 57,000 people. One such place specializing in cricket fights was located in an old factory building and had around 200 patrons, men in their forties and fifties, when the police arrived.[60] Bets at this place started at 5,000 yuan ($600).[60] According to an anonymous source of China Daily, secretive and elusive "luxury games" take place not in Shanghai but in the outlying provinces.[36] Official attitudes about fighting vary from region to region: Hong Kong banned fights altogether; Hangzhou regulates it as a professional sport.[44]

Cricket homes

Male crickets, whether held for fighting or for singing, always live in solitary individual homes or containers. Laufer in his 1927 book wrote that Chinese people sometimes hoarded hundreds of singing crickets, with dedicated cricket rooms filled with many rows of cricket homes. Such houses were filled with "a deafening noise which a Chinese is able to stand for any length of time".[61] Present-day cricket containers take three different shapes: cages are used for trapping and transportation, ceramic jars or pots are used in the summer and autumn, and in the winter the surviving crickets are moved into gourds.[62]

Wooden cages made of tiny rods and planks were once the most common type of insect house. The people of Shanghai and Hangzhou areas still use stool-shaped cages for keeping captive grasshoppers. Elsewhere, cages were historically used for keeping captive cicadas. They were suspended outdoors, at the eaves of the houses and from tree branches. Their use declined when the Chinese concentrated on keeping crickets. Small cages are still used for transporting crickets. Some are curved to follow the shape of a human body; crickets need warmth and prefer to be kept close to the body. The cage is placed in a tao, a kind of protective silk bag, and is ideally carried in the pocket of a shirt.[63] A special type of funnel-shaped wire mesh cage is used to temporarily contain the cricket while its main home is being cleaned.[6]

Ceramic jars or pots with flat lids, introduced in the Ming period, are the preferred type of container for keeping the cricket in summer. Some jars are shaped as a gourd but most are cylindrical. Thick clay walls effectively shield the cricket from excessive heat. Ceramic pots are used for raising cricket larvae until the insect matures to the point when it can be safely transported in a cage or a gourd. The bottom of the jar is filled with a mortar made of clay, lime, and sand. It is levelled at a slant angle of about thirty degrees, smoothed, and dried into a shiny solid mass. In addition to shaping the cricket's habitat, it also defines the acoustic properties of a cricket house. Inside, the jar may contain a cricket "bed" or "sleeping box" (lingfan) made of clay, wood, or ivory, and miniature porcelain "dishes".[64]

Pet crickets spend winters in a different type of container made of a gourd (the hard-shelled fruit of Lagenaria vulgaris). The bottoms of the gourds are filled with lime mortar. The carved lids can be made of jade, coconut shell, sandalwood and ivory; the most common motif employs an ornament of gourd vines, flowers, and fruits. The thickness of the lid and the configuration of vents in it are tailored to enhance the tone of a cricket's song.[65] The ancient art of growing molded gourds was lost during the Cultural Revolution, when the old pastime was deemed inappropriate for Red China. 20th-century cricket enthusiasts like Wang Shixiang had to carve their gourds themselves.[66] Contemporary cricket gourds have carved, rather than naturally molded, surfaces. Molded gourds are being slowly re-introduced since the 1990s by enthusiasts like Zhang Cairi.[67]

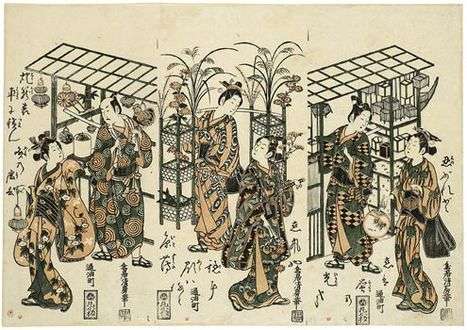

Pet crickets in Japan

The two species most esteemed in Japan, according to Huber et al., are the Homoeogryllus japonicus (bell cricket, suzumushi) and the Xenogryllus marmoratus (pine cricket, matsumushi).[68][note 6] Lafcadio Hearn in his 1898 book named the third species, kirigirisu (Gampsocleis mikado).[69] The Japanese identified and described the most musical cricket haunts centuries ago, long before they began keeping them at home.[70] According to Hearn, the Japanese esteemed crickets far higher than the cicadas, which were considered "vulgar chatterers" and were never caged.[71]

The first poetic description of matsumushi is credited to Ki no Tsurayuki (905 A.D.).[72] Suzumushi is featured in an eponymous chapter of The Tale of Genji (1000–1008 A.D.) which, according to Hearn, is the oldest Japanese account of an insect hunt.[73] Crickets and katydids (mushi) were the staple symbols of autumn in haiku poetry.[74] The Western culture, unlike its Japanese counterpart, regards crickets as symbols of summer. American film producers routinely insert clips of cricket sounds to tell the audience that the action takes place in summer.[75]

Cricket trade emerged as a full-time occupation in the 17th century.[74] The poet Takarai Kikaku complained that he could not find any mushiya (cricket dealers) in the city of Edo; according to Hearn this meant that he expected to find such dealers there.[76] Tokyo lagged behind other cities; regular trade there emerged only at the end of the 18th century.[77] A food vendor named Chuzo, who collected crickets for fun, suddenly discovered considerable demand for them among his neighbors and started trading in wild crickets.[78] One of his customers, Kiriyama, succeeded in breeding three species of crickets. He partnered with Chuzo in the business, which was "profitable beyond expectations".[79] Chuzo was flooded with orders and switched exclusively to wholesale operations, supplying crickets to street dealers and collecting royalties from cage makers.[80] During the Bunsei period the government contained competition between cricket dealers by limiting them to thirty-six, in a guild known as Ōyama-Ko (after Mount Ōyama) or, alternatively, the Yedo Insect Company.[81] At the end of the 19th century cricket trade was dominated by two houses: Kawasumo Kanesaburo and his network supplied wild-caught insects, and the Yumoto house specialized in breeding crickets off-season. They dealt in twelve species of wild-caught and nine species of artificially-bred crickets.[82]

This tradition, which peaked in the 19th century, is now largely gone but crickets are still sold at pet shops.[68] A large colony of suzumushi crickets thrives at the altar of the Suzumushi Temple in Kyoto. These crickets have no particular religious significance; they are retained as a tourist attraction.[74]

Pet crickets in the West

European naturalists studied crickets since the 18th century. William Gould described feeding ant nymphs to a captive mole cricket for several months.[83] The European approach to cricket breeding has been popularized by Jean-Henri Fabre. Fabre wrote that breeding "demands no particular preparations. A little patience is enough."[84] According to Fabre, home breeding may start as early as April or May with the capture of a couple of field crickets. They are placed in a flower pot with "a layer of beaten earth" inside, and a tightly fitting lid. Fed only with lettuce, Fabre's cricket couple laid five to six hundred eggs, and practically all of them hatched.[85]

Crickets are a common subject of children's books on nature and advice on keeping pet crickets are plentiful. An ideal home habitat for a cricket is a large transparent jar or a small terrarium with at least two inches of damp soil on the bottom. There must be plenty of shelter where the crickets can hide; children's books and industrial breeders recommend egg-crate shells. The top of the terrarium must be tightly covered with a lid or nylon mesh.[86]

Drinking water is supplied by offering crickets a wet sponge or spraying their container, but never directly: crickets easily drown even in small dishes of water. Crickets feed on all kinds of fresh fruit and greens;[1] industrial breeders also feed bulk quantities of dry fish food – Daphnia and Gammarus.[86] Contrary to the Eastern approach of keeping males in solitary cells, keeping males together is acceptable: According to Amato, protein-rich diet reduces the males' drive to fight.[87]

Industrial cricket farming

Chinese breeders of the 21st century strive to extend the fighting season to the whole year. They advertise farm-bred "designer bugs" as super-fighters and agree that their technology is "completely counter to the natural process". However, they refuse to use hormones or the practice of arming crickets with steel implants.[44] As of 2003, these farm-bred crickets retailed for only around $1.50 a head, ten times lower than average wild-caught Shandong cricket.[44] Breeding is a risky business: Chinese cricket farms are regularly wiped out by an unknown disease.[44] Fungal diseases are manageable,[88] but crickets have no defenses against cricket paralysis virus (CrPV), which almost certainly kills the entire population. The virus was first isolated in Australia around 1970. The worst outbreak in Europe occurred in 2002. The cosmopolitan virus is carried by a multitude of invertebrate hosts, including drosophilae and honey bees, which are not affected by the disease.[89][note 7]

Almost all crickets farmed in the United States are Acheta domesticus.[74] The American cricket industry does not disclose its earnings; in 1989 Huber et al. estimated it at $3,000,000 annually.[74] Most of these crickets were not pets, but fish bait and animal food. The largest shipment, of 445 metric tons, was reported by Purina Mills in 1985.[74] A decade later individual cricket farms like the Bassett Cricket Ranch in Visalia, California easily surpassed the million-dollar mark. By 1998 Bassett shipped two million crickets a week.[90] The Fluker Cricket Farm in Louisiana exceeded $5,000,000 in annual sales in 2001[91] and became a staple subject of American business school textbooks.[note 8]

The zoos of the Old World breed Acheta domesticus, Gryllus bimaculatus, and Gryllus assimilis. Their cricket farms usually rotate four generation ("four crates") of insects. One generation or one physical crate is used for mating and incubation of eggs, which takes from seven to twelve days. One male usually mates to three or four females. Females are discarded (and fed to zoo animals) immediately after laying the eggs: their life span is too short to give them a second chance. Three other generations, spaced by the same seven to twelve days, are for raising the larvae, which takes 4–5 weeks. Thus the zoos restock their live food supply practically every week.[92]

British zoos breed crickets in deliberate attempts to restore the nearly extinct wild populations. In the late 1980s the British population of Gryllus campestris shrunk to a single colony of around 100 individual insects. In 1991 the species became the subject of the national Species Recovery Program. Each year, three pairs of subadult crickets were caught in the wild and bred in a controlled lab environment to preserve the gene pool of the mother colony. The London Zoo raised 17,000 crickets; the field biologists laid down seven new cricket colonies, four of which survived into the 21st century. The program became a model for similar efforts in other countries.[93] In the same period the London Zoo bred the more demanding wart-biter (Decticus verrucivorus), also resulting in the establishment of persistent colonies in the wild.[88]

Notes

- Yutaka Suga, p. 79, discusses another theory dating cricket fights to the 8th century. However, the earliest reliable evidence is dated 12th century.

- Levchenko, p. 125, warns against uncontrolled feeding of crickets to spiders immediately before and during moulting. A cricket will eagerly attack a much larger but defenseless moulting spider.

- This is a simplified model of Teleogryllus commodus behaviour. Huber et al., pp. 48–54, discuss various other means of sexual recognition in different species.

- See Suga, pp. 77–78, for a review of the evolution of flower, bird, fish, insect culture.

- Burrowing crickets use funnel-shaped entrances to their nests as natural resonators to amplify their songs. A singing cricket literally faces its own burrow and can instantly hide underground. – Huber et al., p. 44.

- Contemporary English translators renders suzumushi as bell cricket, matsumushi as pine cricket – see translator's notes to The Tale of Genji, pp. 445 and 1135.

- Honey bees suffer from two related but different viruses – acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV) and chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), discovered in 1863. – Christian and Scotti, p. 310.

- The Fluker case studies are discussed in Steven P. Robbins (2001). Organizational Behavior. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-189095-6.; Garnter and Bellamy (2009). Enterprise. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-324-13085-6; Thill and Bovee (1999). Excellence in business communication. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-781501-8 etc.

References

- Amato, pp. 43–44.

- Gordh et al., p. 415.

- John L. Foltz (1998). "ENY 3005 Family Identification: Orthoptera: Gryllidae" Archived 2010-02-01 at the Wayback Machine. University of Florida. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Kompantseva et al., p. 103.

- Laufer, p.4; Ryan et al., p. 4.

- Laufer, p. 16; Ryan et al., p. 34.

- Thomas J. Walker, (1999). "House cricket – Acheta domesticus". University of Florida. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Turner, pp. 161, 165–166, 171.

- Laufer, pp. 16–17; Ryan et al., pp. 22, 34.

- Huber et al., p. 44.

- Laufer, pp. 3–4; Ryan et al., pp. 3–4. Huber et al., pp. 44–46, explain that different species "sing" in different periods of the day or night, for no longer than three hours continuously.

- Huber et al., pp. 55–56.

- Huber et al., p. 46, describe this behaviour in Gryllus integer.

- Huber et al., p. 45.

- Judge and Bonanno, p. 1.

- Judge and Bonanno, pp. 1, 7.

- Laufer, pp. 4–5; Ryan et al., p. 5.

- Heiser, p. 136.

- Laufer, pp. 5–6; Ryan et al., p. 9.

- Laufer, p.6; Ryan et al., p.9.

- Laufer, p. 10. See also "Fighting won't bug these crickets". China Daily, 2003-09-10. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Ryan et al., p. 7.

- Laufer, p. 10.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 79.

- Laufer, p. 6; Ryan et al., p. 11. Note that the spelling of Chinese names in Laufer's 1927 book, reproduced as-is by Ryan, may differ from modern English renditions.

- Laufer, pp. 22–26; source text: Yuan, pp. 89–90.

- Welch, p. 95.

- Ryan et al., p. 30; Finch and Zhang, pp. 13–15, 21.

- Cheng Angi (2009). "Empty nest". China Daily. 2009-12-26. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Sklarew, pp. 101–102.

- Jin and Yen, p. 211.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 85.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 80.

- Yutaka Suga, pp. 79–80.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 83.

- "Fighting won't bug these crickets". China Daily, 2003-09-10. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Huber, p. 39.

- Laufer, pp. 12–13; Ryan et al., p. 23.

- Yutaka Suga, pp. 81–82.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 81.

- Piassetsky, p. 100.

- Laufer, pp. 10–12.

- Xiao Changyan (2006). "Just cricket". China Daily. 2006-08-11. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- James T. Areddy (2003). "In Shanghai, the Autumn Game Just Isn't Cricket Anymore". The Wall Street Journal. December 2, 2009.

- Yutaga Suga, p. 82.

- Yutaga Suga, pp. 82,83,85.

- Yutaka Suga, pp. 84–86.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 86.

- "China cricket culture festival begins Sept 9". China Daily, August 8, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 89.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 88.

- Laufer, p. 15.

- Laufer, p. 18; Ryan et al., p. 36.

- Laufer, p. 19; Yutaka Suga, p. 90.

- Ryan et al., p. 36.

- Laufer, p. 16; Ryan et al., p. 34; Yutaka Suga, p. 91.

- Laufer, p. 19.

- Yutaka Suga, p. 91.

- Laufer, pp. 20–21; Ryan et al., p. 39.

- Cao Li (2006). "Cricket gambling den busted in Shanghai". China Daily. 2004-11-16. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- Laufer, p. 13; Ryan et al., p. 27.

- Laufer, p. 14.

- Ryan et al., pp. 23–26.

- Laufer, p. 14; Ryan et al., pp. 27–28; Yutaka Suga, pp. 87–88.

- Laufer, pp. 14–15; Ryan, pp. 21, 30.

- Barrass, p. 158.

- Ryan et al., p. 30; Finch and Zhang, pp. 15, 1.

- Huber et al., p. 40.

- Hearn, pp. 46, 48.

- Hearn, pp. 46–47.

- Hearn, p. 42.

- Hearn, p. 61.

- Hearn, p. 44.

- Huber et al., p. 41.

- Huber, p. 42.

- Hearn, p. 46.

- Hearn, p. 48.

- Hearn, p. 49.

- Hearn, p. 50.

- Hearn, p. 51.

- Hearn, pp. 53–54.

- Hearn, p. 55-56.

- Rennie, p. 242.

- Fabre, p. 132.

- Fabre, pp. 132–134.

- Amato, pp. 43–44; Kompantseva, pp. 102–105.

- Amato, p. 44.

- Pearce-Kelly et al., p. 63.

- Jan et al., p. 285; Christian and Scotti, pp. 305–308.

- Menzel and d'Aluisio, p. 181.

- Scarborough and Zimmerer, p. 5.

- Kompantseva et al., pp. 102–105.

- Pearce-Kelly et al, p. 62.

Sources

- Amato, Carol A. (2002). Backyard Pets: Activities for Exploring Wildlife Close to Home. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-41693-2.

- Barrass, Gordon S. (2002). The Art of Calligraphy in Modern China. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23451-0.

- Christian, Peter D. and Scotti, Paul D. (1998). Picornalike Viruses of Insects, in: Miller, Lois K. et al. (1998). The Insect Virus. Springer. ISBN 0-306-45881-0.

- Fabre, Jean-Henri (1943 ed.). Social Life in the Insect World. Pelican books. Reprint: ISBN 978-1-60303-488-3.

- Finch, Betty and Zhang, Guojun (2006). The Immortal Molded Gourds of Mr. Zhang Cairi. Betty Finch. ISBN 0-9700338-5-0.

- Gordh, George et al. (2003). A Dictionary of Enthomology. CABI. ISBN 0-85199-655-8.

- Hearn, Lafcadio (1898). Insect Musicians, from Exotics and Retrospectives. Boston.

- Heiser, Charles Bixler (1993). The Gourd Book. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2572-1.

- Huber, Franz et al. (1989). Cricket Behavior and Neurobiology. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2272-8.

- Jan, E. et al. (2001). Initiator MettRNAindependent Translation Mediated by an Internal Ribosome Entry Site , in: The Ribosome, 2001, vol. 66. CSHL Press, ISBN 0-87969-620-6. pp. 285–300.

- Jin, X.-B. and Yen, A.L. (1998). "Conservation and the Cricket Culture in China". Journal of Insect Conservation. Springer. Volume 2, Numbers 3–4, 211–216, doi:10.1023/A:1009616418149.

- Judge, Kevin A. and Bonanno, Vanessa L. (2008). "Male Weaponry in a Fighting Cricket". PLoS ONE 3(12): e3980. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003980. Published December 24, 2008.

- Kompantseva, T. V. et al. (2005). "Husbandry of Food Insects at the Insectarium of the Moscow Zoo" (in Russian with an English summary), in "Invertebrates in Zoos Collections". Second International Workshop. Moscow, 15–20 November 2004. A Moscow Zoo publication. pp. 102–105.

- Laufer, Berthold (1927)."Insect Musicians & Cricket Champions". Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

- Levchenko, S. L. (2005). "The Home Insectarium" (in Russian with an English summary), in: "Invertebrates in Zoos Collections". Second International Workshop. Moscow, 15–20 November 2004. A Moscow Zoo publication. pp. 124–125.

- Menzel, Peter Menzel and Faith D'Aluisio, Faith (1998). Man Eating Bugs: The Art and Science of Eating Insects. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1-58008-022-7.

- Pearce-Kelly, Paul et al. (2007)"The Conservation Value of Insect Breeding Programmes", in Alan J. A. Stewart, T. R. New, Owen T. Lewis (editors, 2007). Insect Conservation Biology: Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society's 23rd Symposium. CABI. ISBN 1-84593-254-4. pp. 57–75.

- Piassetsky, Pavel (1884). Russian Travellers in Mongolia and China. In Two Volumes. Volume 1. Chapman and Hall, London. Reprint: ISBN 1-4021-7753-4, ISBN 1-4021-2424-4.

- Rennie, James (1838). Insect Architecture. London: Charles Knight and Co.

- Ryan, Lisa Gail et al. (1996). Insect Musicians & Cricket Champions: A Cultural History of Singing Insects in China and Japan. China Books. ISBN 0-8351-2576-9. The book contains large excerpts from the older publications by Laufer and Hearn, included in this bibliography, who are credited as co-authors. Where possible, original statements by Laufer and Hearn are credited to them directly.

- Murasaki Shikibu, Royall Tyler (translator) (2003). The Tale of Genji. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-243714-8.

- Scarborough, Norman M. and Zimmerer, Thomas (2000). Effective Small Business Management: An Entrepreneurial Approach. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-080708-7.

- Sklarew. Bruce H. (1998). Bertolucci's The Last Emperor: Multiple Takes. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2700-1.

- Turner, J. Scott (2000). The Extended Organism: the Physiology of Animal-Built Structures. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00151-6.

- Yutaka Suga (2006). "Chinese Cricket-Fighting". International Journal of Asian Studies (Cambridge University Press). Vol. 3, no. 1, 2006. pp. 77–93. doi:10.1017/S:1479591405000239.

- Welch, Patricia Bjaaland (2008). Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3864-X.

- Haiwang Yuan (2006). The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales From the Han Chinese. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 1-59158-294-6.

External links

- Listen to the autumn. Resources on Cricket Culture at Bolingo. Includes full texts of out-of-print books by Laufer, Hearn etc.

- Flash app with voice of Japanese Cricket