Crotone

Crotone (/kroʊˈtoʊneɪ, krəˈ-/, Italian: [kroˈtoːne] (![]()

Crotone | |

|---|---|

| Città di Crotone | |

Panorama of Crotone | |

Coat of arms | |

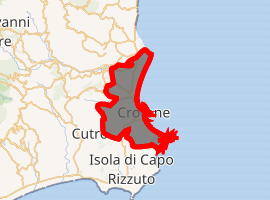

Location of Crotone

| |

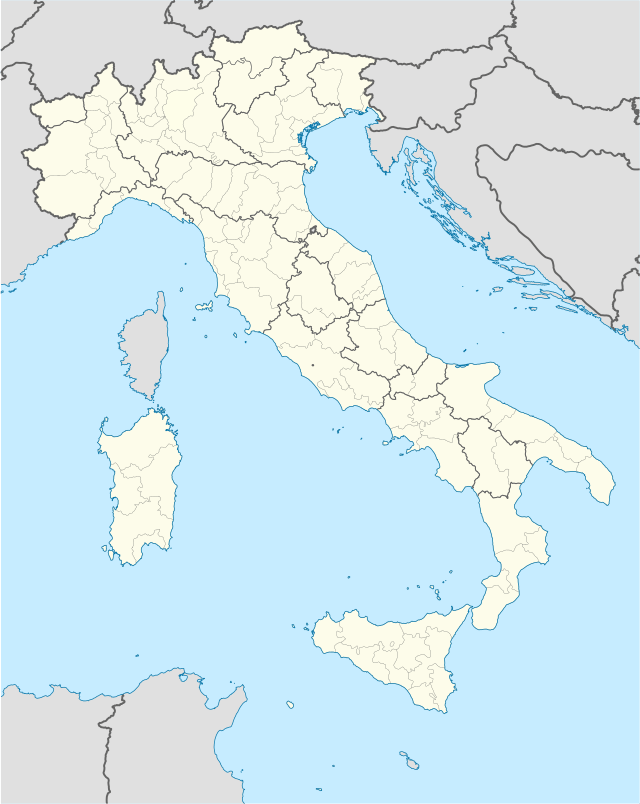

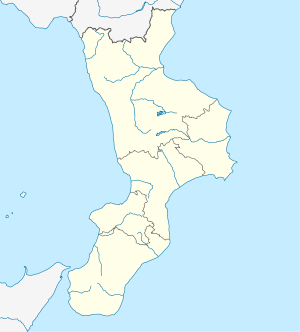

Crotone Location of Crotone in Italy  Crotone Crotone (Calabria) | |

| Coordinates: 39°05′N 17°07′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Calabria |

| Province | Crotone (KR) |

| Frazioni | Papanice, Apriglianello, Carpentieri, Cipolla, Farina, Gabella Grande, Iannello, Maiorano, Margherita |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ugo Pugliese |

| Area | |

| • Total | 179.8 km2 (69.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population (31 August 2018)[2] | |

| • Total | 64,603 |

| • Density | 360/km2 (930/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Crotonesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 88900 |

| Dialing code | 0962 |

| Patron saint | Dionysius the Areopagite |

| Saint day | October 9 |

| Website | Official website |

History

Croton's oikistes (founder) was Myscellus who came from the city of Rhypes in Achaea in the northern Peloponnese. He established the city in c. 710 BC and it soon became one of the most flourishing cities of Magna Graecia with a population between 50,000 and 80,000 around 500 BC.[3] Its inhabitants were famous for their physical strength and for the simple sobriety of their lives. From 588 BC onwards, Croton produced many generations of victors in the Olympics and the other Panhellenic Games, the most famous of whom was Milo of Croton. According to Herodotus (3.131), the physicians of Croton were considered the foremost among the Greeks, and among them Democedes, son of Calliphon, was the most prominent in the 6th century BC. Accordingly, he traveled around Greece and ended up working in the court of Polycrates, tyrant of Samos. After the tyrant was murdered, Democedes was captured by the Persians and brought to King Darius, curing him of a dislocated ankle. Democedes' fame was, according to Herodotus, the basis for the prestige of Croton's physicians.[4] Pythagoras founded his school, the Pythagoreans, at Croton c. 530 BC. Among his pupils were the early medical theorist Alcmaeon of Croton and the philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer Philolaus. The Pythagoreans acquired considerable influence with the supreme council of one thousand by which the city was ruled. Sybaris was the rival of Croton until 510 BC, when Croton sent an army of one hundred thousand men, commanded by the wrestler Milo, against Sybaris and destroyed it. Shortly afterwards, however, an insurrection took place, led by a prominent citizen, Cylon, by which the Pythagoreans were driven out and a democracy established.

In 480 BC, Croton sent a ship in support of the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis (Herodotus 8.47), but the victory of Locri and Rhegium over Croton in the same year marked the beginning of its decline. It was replaced by Heraclea as headquarters of the Italiote League. Dionysius, the tyrant of Syracuse, aiming at hegemony in Magna Graecia, captured Croton in 379 BC and held it for twelve years. Croton was then occupied by the Bruttii, with the exception of the citadel, in which the chief inhabitants had taken refuge; these soon after surrendered, and were allowed to withdraw to Locri.

In 295 BC, Croton fell to another Syracusan tyrant, Agathocles. When Pyrrhus invaded Italy (280-278, 275 BC), it was still a considerable city, with twelve miles (19 km) of walls, but after the Pyrrhic War, half the town was deserted (Livy 24.3). What was left of its population submitted to Rome in 277 BC. After the Battle of Cannae in the Second Punic War (216 BC), Croton was betrayed to the Brutii by a democratic leader named Aristomachus, who defected to the Roman side. Hannibal made it his winter quarters for three years and the city was not recaptured until 205 or 204 BC. In 194 BC, it became the site of a Roman colony. Little more is heard of it during the Republican and Imperial periods, though the action of one of the more significant surviving fragments of the Satyricon of Petronius is set in Croton.

Around 550, the city was unsuccessfully besieged by Totila, king of the Ostrogoths. At a later date it became a part of the Byzantine Empire. Around 841, the Republic of Venice sent a fleet of 60 galleys (each carrying 200 men) to assist the Byzantines in driving the Arabs from Crotone, but it failed.[5] About 870, it was sacked by the Saracens, who put to death the bishop and many people who had taken refuge in the cathedral but were not able to occupy the city. Over a hundred years later, Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor, mounted a campaign in southern Italy to reduce the power of the Byzantines. Later on Crotone was conquered by the Normans. In 1806, it was occupied and sacked by the British, and later on by the French. Thereafter it shared the fate of the Kingdom of Naples—including the period of Spanish rule of which the 16th-century castle of Charles V, overlooking modern Crotone, serves as a reminder—and its successor, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was conquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860 and incorporated into the new Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

Crotone's location between the ports of Taranto and Messina, as well as its proximity to a source of hydroelectric power, favored industrial development during the period between the two World Wars. In the 1930s its population doubled. However, after the two main employers, Pertusola Sud and Montedison, collapsed by the late 1980s, Crotone was in economic crisis, with many residents losing their jobs and leaving to find work elsewhere. In 1996, the river Esaro flooded the city, which dealt a further blow to the city's morale. Since that low point, the city has undergone urban renewal and risen in quality-of-life rankings.

Geography

Climate

Crotone enjoys a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa).

| Climate data for Crotone Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.2 (108.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.6 (101.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

20.7 (69.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.2 (20.8) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 96.2 (3.79) |

87.1 (3.43) |

94.1 (3.70) |

52.7 (2.07) |

24.7 (0.97) |

5.2 (0.20) |

11.9 (0.47) |

24.0 (0.94) |

53.9 (2.12) |

115.8 (4.56) |

116.2 (4.57) |

109.8 (4.32) |

791.6 (31.14) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 8.0 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 8.5 | 63 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 68 | 62 | 57 | 62 | 64 | 74 | 78 | 75 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.2 | 138.3 | 170.5 | 195.0 | 251.1 | 279.0 | 313.1 | 291.4 | 231.0 | 189.1 | 144.0 | 117.8 | 2,450.5 |

| Source 1: Servizio Meteorologico (1971–2000 data)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Servizio Meteorologico (1961–1990 data on humidity and sunshine)[7] | |||||||||||||

Main sights

- The Cathedral, originally from the 9th to 11th centuries, but largely rebuilt. It has a neo-classical façade, while the interior has a nave with two aisles, with Baroque decorations. Noteworthy are a baptismal font (12th century) and the Madonna di Capo Colonna, the icon of the Black Madonna which, according to the tradition, was brought from East in the first years of the Christian era.

- The 16th-century Castle of Charles V. It houses the Town Museum, with findings excavated in the ancient site of Kroton. Notable are also the remnants of the walls, of the same century, and of various watchtowers.

- The ancient castle built on an island, with accessibility on foot limited to a narrow strip of land, is referred to as Le Castella.

Government

Transportation

Crotone Airport (Sant'Anna Airport) is served by Italiatour.it and other charter airlines. Crotone also has a railway station, although much of the tourism traffic is served by the Salerno-Reggio Calabria highway and the National Road (called 106 Ionica) leading all the Jonic (eastern) coast from Taranto to Reggio Calabria. In recent time Crotone Port has been used by visitors on yacht charter cruising vacations.

Culture

Museums

Crotone hosts a national archaeological museum, a municipal museum, a municipal art gallery, and a provincial museum of contemporary art, as well as the Antiquarium di Torre Nao.

Sport

F.C. Crotone is a football club in Serie A. The team was promoted to top flight Serie A for the first time in its history for the 2016–17 season, and after one year in Serie B, was again promoted to play in Serie A for the 2020–21 season.

Achei Crotone is an American football club in Italy's 3rd division. It was established in 1989 and is considered one of the most storied teams in Italy.

Notable people

- Milo of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Phayllos of Croton (Olympic athlete/war hero in battle of Salamina)

- Astylos of Croton (5th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Diognetus of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Eratosthenes of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Glycon of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Hippostratus of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Isomachus of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Lycinus of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Tisicrates of Croton (5th century BC – Olympic athlete)

- Democedes of Croton (6th century BC – physician)

- Calliphon of Croton (6th century BC – physician)

- Philippus of Croton (6th century BC – Olympic athlete/war hero)

- Aristomachus of Croton (ancient party leader of Croton during the Hannibalian war)

- Alcmaeon of Croton (5th century BC – philosopher and medical theorist)

- Arignote (6th century BC – Pythagorean philosopher)

- Philolaus of Croton (5th century BC – pythagorean philosopher)

- Pythagoras (mathematician and philosopher – lived in Crotone c. 530 BC)

- Nicholas of Crotone (13th century bishop)

- Vincenzo Scaramuzza (pianist and music teacher – born in Crotone)

- Rino Gaetano (singer – born in Crotone)

- Sergio Cammariere (singer – born in Crotone)

- Vincenzo Iaquinta (footballer – born in Crotone)

- Autoleon (ancient war hero)

Literary reference

Crotone appears in the Philippine national epic Florante at Laura as the Kingdom of Krotona. The poem narrates this as the homeland of the protagonist Florante's mother, Princess Floresca.

In Petronius' Satyricon, which survives in fragments, the narrator and his friends arrive at Croton, famous for its legacy hunters. The narrator's companion, the manic poet Eumolpus, poses as a childless, rich old man. Upon arrival to the city, Philomela, a citizen of Croton, seduces Eumolpus by means of her children. The extant portion of the Satyricon ends with Eumolpus explaining that the people of Croton must agree to eat his dead body if they wish to claim his inheritance.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Crotone is twinned with:

See also

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Jarde, A. (2013). The Formation of the Greek People. Routledge. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-136-19586-0.

- Herodotus, The Histories, p. 226, Penguin Classics

- J. Norwich, A History of Venice, 32

- "Crotone (KR) 161 m. s.l.m. (a.s.l.)" (PDF). Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Stazione 350 Crotone medie mensili periodo 61 - 90". Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Grecia e Magna Grecia: incontro Giannitsa e Crotone Archived November 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine(in Italian)

- J. Banaszkiewicz, "Ein Ritter flieht oder wie Kaiser Otto II. sich vom Schlachtfeld bei Cotrone rettete," Frühmittelalterliche Studien, 40 (2006), 145–166.