Cornelia, Georgia

Cornelia is a city in Habersham County, Georgia, United States. The population was 4,160 at the 2010 census,[7] up from 3,674 at the 2000 census. It is home to one of the world's largest apple sculptures, which is displayed on top of an obelisk-shaped monument. Cornelia was the retirement home of baseball legend Ty Cobb who was born nearby, and was a base of operation for production of the 1956 Disney film The Great Locomotive Chase that was filmed along the Tallulah Falls Railway that ran from Cornelia northward along the rim of Tallulah Gorge to Franklin, North Carolina.

Cornelia, Georgia | |

|---|---|

Downtown Cornelia | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Home of the Big Red Apple | |

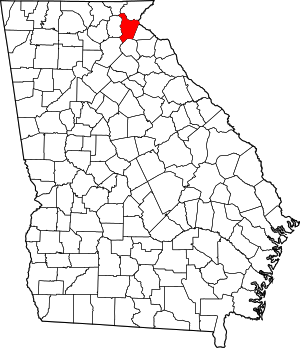

Location in Habersham County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 34°30′49″N 83°31′51″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Habersham |

| Blaine | 1860 |

| Cornelia | October 22, 1887 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayoral, elected democratically by popular vote. |

| • Mayor | John Borrow[1] |

| • City Manager | Donald Anderson, Jr.[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.21 sq mi (10.89 km2) |

| • Land | 4.16 sq mi (10.77 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.12 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,500 ft (457 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 4,160 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 4,683 |

| • Density | 1,126.53/sq mi (435.01/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 30531 |

| Area code(s) | 706 |

| FIPS code | 13-19728[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0355323[6] |

| Website | corneliageorgia |

Geography

Cornelia is located in southern Habersham County at 34°30′49″N 83°31′51″W (34.513716, -83.530942).[8] It is bordered to the east by Mount Airy and to the southwest by Baldwin.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.0 square miles (10.3 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 1.06%, are water.[7]

History

Cornelia was originally called "Blaine", and under the latter name had its start in the early 1870s when the Charlotte Airline Railroad was extended to that point.[9] The Georgia General Assembly incorporated the place in 1887 as the "Town of Cornelia".[10]

Lore

Cornelia abounds in historical lore. Near the city is the Wofford Trail, on which many stagecoach robberies occurred. The last railroad holdup in Georgia took place at Cagle's Crossing, which is a few miles south of Cornelia.[11] The whole of Habersham County was extremely loyal to the Confederacy and was known, along with the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and countless other fertile, out-of-the-way places as the "breadbasket of the Confederacy", as thousands of bushels of wheat and corn were supplied to the troops from this area alone. After the fall of Atlanta, a detachment of Sherman's cavalry was sent to raid the county; but the Confederate Home Guard, made up of men too old for military duty, left the mountains on which Cornelia is situated and met the Yankee raiders at a narrow pass about four miles east of the town. By making considerable noise and stirring up clouds of smoke, they scared off the enemy and saved the area from complete devastation. Today this skirmish is remembered as "The Battle of the Narrows".[12] A few years after the war, a young school teacher named William Herschel Cobb and his wife Amanda settled near the site of this skirmish, and she gave birth in 1886 to one of the greatest baseball players of all time, Ty Cobb.

Education

Cornelia has been helped in its growth by its good schools. In the early days, the school system was owned and operated by the town of Cornelia. Each student provided their books and paid a tuition fee, half payable before Christmas, with the balance due after Christmas. The school principal would determine what books would be needed and would then send someone to Atlanta to order books and supplies personally from the publishers (Maxwell, p. 4). Among the first schools was the Kimsey Institute, located on land given by T.J. Kimsey. The First Baptist Church was organized there; for many years it was used for both school and church. Willie Grant and J.T. Wise were two of the early teachers. After attendance outgrew the early frame building in 1897, another school was built with Professor A.E. Booth elected as principal. According to the document published by the Habersham County Department of Education in 1937, Professor Booth added a training course for teachers, and students were attracted to this school from all sections of northeast Georgia (p. 21). Cornelia Normal Institute was chartered on May 27, 1901. It was supported by many progressive citizens, including D.A. York, J.T. King, J.A. Walker, W.D. Burch, L.J. Ragsdale, J.T. Peyton, L.L. Lyon, J.W. Peyton, J.J. Kimsey, I.T. Sellers, J.C. McConnell, J.W. McConnell, A.J. Brown, R.C. Moss, T.S. Wells, John S. Crawford, George Erwin, and J.C. Edwards. In 1952, the schools in Habersham were consolidated. The elementary schools had been kept in each town but two high schools were built, one to serve each end of the county. Prior to 1952, Cornelia Public School served all the students residing in Cornelia. The high school curriculum included college preparatory and business classes, athletics for both males and females, music, and "expression" (speech classes). The school's first graduates were in the Class of 1899 and included Martin L. York, Charles Crunkleton, Calvania T. York, Albert N. McConnell, Wylie G. Light, and Ida K. Baugh.

German and Swiss immigrants used their wine-making skills to create an industry in the 1880s that flourished until a prohibition law stopped it. Cotton, timber and lumber products, and the apple and peach industries were also important to the success of the area. Riegel Textile built one of the region's first major industrial facilities in 1966 with what was then an ultra-modern, cutting edge textile mill designed by Bill Pittendreigh in the neighboring community of Alto. As with any city, there were a number of businesses, but hotels contributed greatly to the growth and development of the city in its early history.

The Big Red Apple

Cornelia's Big Red Apple, located at the old train depot in downtown, pays homage to the apple and apple growers of the county. Built of steel and concrete in 1925, the statue, according to Habersham County, weighs 5,200 pounds (2.4 t) and is 7 feet (2.1 m) high.

Towards the end of World War I, "extension agents" began to play a very important role in northeast Georgia. These people, as a group, supported the end of the one-crop (cotton) economy. Throughout the state they began to educate farmers in crop diversification so that if one crop failed income from other crops could support the family. In Gwinnett, Cherokee and Hall counties, farmers increased production of dairy products. The peach crop in Bartow County was expanded. In Habersham and Gilmer counties farmers increased production of apples and peaches.

The extension agents' push for this diversity seemed almost prescient, for in 1922 the boll weevil began the systematic destruction of cotton crops in the state of Georgia. By 1924 cotton output had dropped to 50% of earlier levels. In 1925 the people of Cornelia realized that the apple had been a key in preventing the scourge that destroyed other counties and drove rural families to cities like Atlanta and Macon. The concept for the statue was born, thanks in part to the newly formed Kiwanis Club.

At the dedication on June 4, 1926, many notables attended, including Senator Walter F. George. Because apple sales were off dramatically, in 1932 local farmers decided to put them in cold storage until the following spring, but the sales did not materialize, so the farmers were not only out the cost of raising the crop, they were also out the cost of storing the crop. By the summer of 1933, the apples that had saved the county less than 10 years earlier nearly destroyed it.

Through the years downtown Cornelia changed dramatically. As the railroad era passed the old depot was closed and boarded up, and the once central location was only a side street. A recent renovation has brought the depot back to life, and the quiet Big Red Apple is the focal point of a yearly festival[13] held the first week in October and a 5K road race held at the end of October.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 175 | — | |

| 1900 | 467 | 166.9% | |

| 1910 | 1,114 | 138.5% | |

| 1920 | 1,274 | 14.4% | |

| 1930 | 1,542 | 21.0% | |

| 1940 | 1,808 | 17.3% | |

| 1950 | 2,424 | 34.1% | |

| 1960 | 2,936 | 21.1% | |

| 1970 | 3,014 | 2.7% | |

| 1980 | 3,203 | 6.3% | |

| 1990 | 3,219 | 0.5% | |

| 2000 | 3,674 | 14.1% | |

| 2010 | 4,160 | 13.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 4,683 | [4] | 12.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

As of the census[5] of 2010, there were 4,160 people, 1,495 households, and 1,495 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,071.3 people per square mile (413.6/km2). There were 1,728 housing units at an average density of 469.7 per square mile (181.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 67.7% White, 5.7% African American, 0.9% Native American, 4.2% Asian (3.0% Laotian), 0.6% Pacific Islander, 16.5% from other races, and 4.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 34.8% of the population (26.7% Mexican).

There were 1,016 households, out of which 24.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.6% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.09.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 23.4% under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 17.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,111, and the median income for a family was $42,041. Males had a median income of $25,505 versus $20,404 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,701. About 8.8% of families and 13.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.1% of those under age 18 and 20.2% of those age 65 or over.

References

- "Mayor and Commission". City of Cornelia. 2020. Archived from the original on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- "City Manager's Office". City of Cornelia. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Cornelia city, Georgia". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- Bulletin of the New York Public Library. New York Public Library. 1912. p. 697.

- "The Wofford Trail". The Cartersville News. July 1, 1909

- "The Battle of the Narrows". The GAGenWeb Project.

- "Big Red Apple". City of Cornellia. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.