Concerti grossi, Op. 6 (Handel)

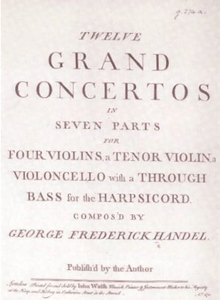

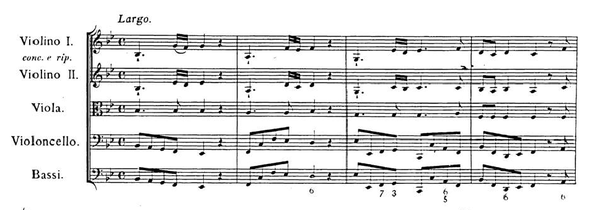

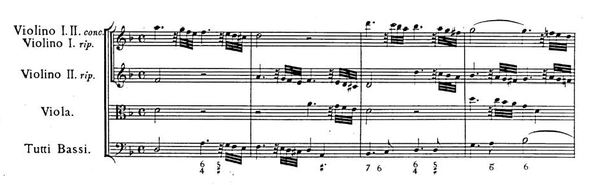

The Concerti Grossi, Op. 6, or Twelve Grand Concertos, HWV 319–330, are 12 concerti grossi by George Frideric Handel for a concertino trio of two violins and violoncello and a ripieno four-part string orchestra with harpsichord continuo. First published by subscription in London by John Walsh in 1739, in the second edition of 1741 they became Handel's Opus 6. Taking the older concerto da chiesa and concerto da camera of Arcangelo Corelli as models, rather than the later three-movement Venetian concerto of Antonio Vivaldi favoured by Johann Sebastian Bach, they were written to be played during performances of Handel's oratorios and odes. Despite the conventional model, Handel incorporated in the movements the full range of his compositional styles, including trio sonatas, operatic arias, French overtures, Italian sinfonias, airs, fugues, themes and variations and a variety of dances. The concertos were largely composed of new material: they are amongst the finest examples in the genre of baroque concerto grosso.

The Musette, or rather chaconne, in this Concerto, was always in favour with the composer himself, as well as the public; for I well remember that HANDEL frequently introduced it between the parts of his Oratorios, both before and after publication. Indeed no instrumental composition that I have ever heard during the long favour of this, seemed to me more grateful and pleasing, particularly, in subject.

— Charles Burney, writing of the performance of the sixth Grand Concerto at the Handel Commemoration, 1784[1]

History and origins

1. The Price to Subscribers is Two Guineas, One Guinea to be paid at the Time of Subscribing, and the other on Delivery of the Books.

2. The whole will be engraven in a neat Character, printed on Good Paper, and ready to deliver to Subscribers by April next.

3. The Subscribers Names will be printed before the Work.

Subscriptions are taken by the Author, at his Home in Brook's-street, Hanover square; and John Walsh in Catherine-street in the Strand.London Daily Post, 29 October 1739

In 1735 Handel had started to incorporate organ concertos into performances of his oratorios. By showcasing himself as composer-performer, he could provide an attraction to match the Italian castrati of the rival company, the Opera of the Nobility. These concertos formed the basis of the Handel organ concertos Op.4, published by John Walsh in 1738.

The first and the last of these six concertos, HWV 289 and HWV 294, were originally written in 1736 to be performed during Alexander's Feast, Handel's setting of John Dryden's ode Alexander's Feast or The Power of Musick – the former for chamber organ and orchestra, the latter for harp, strings and continuo. In addition in January 1736 Handel composed a short and lightweight concerto grosso for strings in C major, HWV 318, traditionally referred to as the "Concerto in Alexander's Feast", to be played between the two acts of the ode. Scored for string orchestra with solo parts for two violins and violoncello, it had four movements and was later published in Walsh's collection Select Harmony of 1740. Its first three movements (allegro, largo, allegro) have the form of a contemporary Italian concerto, with alternation between solo and tutti passages. The less conventional fourth movement, marked andante, non presto, is a charming and stately gavotte with elegant variations for the two violins.[2][3]

Because of changes in popular tastes, the season in 1737 had been disastrous for both the Opera of the Nobility and Handel's own company, which by that time he managed single-handedly. At the close of the season Handel suffered a form of physical and mental breakdown, which resulted in paralysis of the fingers on one hand. Persuaded by friends to take the waters at Aix-la-Chapelle, he experienced a complete recovery. Henceforth, with the exception of Giove in Argo (1739), Imeneo (1740) and Deidamia (1741), he abandoned Italian opera in favour of the English oratorio, a new musical genre that he was largely responsible for creating. The year 1739 saw the first performance of his great oratorio Saul, his setting of John Dryden's Ode for St Cecilia's Day and the revival of his pastoral English opera or serenata Acis and Galatea. In the previous year he had produced the choral work Israel in Egypt and in 1740 he composed L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, a cantata-like setting of John Milton's poetry.

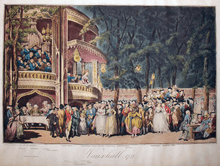

For the 1739–1740 season at the Lincoln's Inn Fields theatre,[4] Handel composed Twelve Grand Concertos to be performed during intervals in these masques and oratorios, as a feature to attract audiences: forthcoming performances of the new concertos were advertised in the London daily papers. Following the success of his organ concertos Op.4, his publisher John Walsh had encouraged Handel to compose a new set of concertos for purchase by subscription under a specially acquired Royal License. There were just over 100 subscribers, including members of the royal family, friends, patrons, composers, organists and managers of theatres and pleasure-gardens, some of whom bought multiple sets for larger orchestral forces. Handel's own performances usually employed two continuo instruments, either two harpsichords or a harpsichord and a chamber organ; some of the autograph manuscripts have additional parts appended for oboes, the extra forces available for performances during oratorios. Walsh had himself very successfully sold his own 1715 edition of Corelli's celebrated Twelve concerti grossi, Op. 6, first published posthumously in Amsterdam in 1714.[5] The later choice of the same opus number for the second edition of 1741, the number of concertos and the musical form cannot have been entirely accidental; more significantly Handel in his early years in Rome had encountered and fallen under the influence of Corelli and the Italian school. The twelve concertos were produced in a space of five weeks in late September and October 1739, with the dates of completion recorded on all but No.9. The ten concertos of the set that were largely newly composed were first heard during performance of oratorios later in the season. The two remaining concertos were reworkings of organ concertos, HWV 295 in F major (nicknamed "the Cuckoo and the Nightingale" because of the imitations of birdsong in the organ part) and HWV 296 in A major, both of which had already been heard by London audiences earlier in 1739. In 1740 Walsh published his own arrangements for solo organ of these two concertos, along with arrangements of four of the Op. 6 concerti grossi (Nos. 1, 4, 5 and 10).[6]

The composition of the concerti grossi, however, because of the unprecedented period of time laid aside for their composition, seem to have been a conscious effort by Handel to produce a set of orchestral "masterpieces" for general publication: a response and homage to the ever-popular concerti grossi of Corelli as well as a lasting record of Handel's own compositional skills.[7] Despite the conventionality of the Corellian model, the concertos are extremely diverse and in parts experimental, drawing from every possible musical genre and influenced by musical forms from all over Europe.

The ten concertos that had been newly composed (all those apart from Nos. 9 and 11) received their premières during the performances of oratorios and odes during the winter season 1739–1740, as evidenced by contemporary advertisements in the London daily papers. Two were performed on November 22, St Cecilia's Day, during performances of Alexander's Feast and Ode for St Cecilia's Day; two more on December 13 and another four on February 14. Two concertos were heard at the first performance of L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato at the end of February; and two more in March and early April during revivals of Saul and Israel in Egypt. The final pair of concertos were first played during a performance of L'Allegro on April 23, just two days after the official publication of the set.[8]

Movements

| HWV | No. | Key | Composed | Movements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 319 | 1 | G major | 29 September 1739 | i. A tempo giusto – ii. Allegro – iii. Adagio – iv. Allegro – v. Allegro |

| 320 | 2 | F major | 4 October 1739 | i. Andante larghetto – ii. Allegro – iii. Largo – iv. Allegro, ma non troppo |

| 321 | 3 | E minor | 6 October 1739 | i. Larghetto – ii. Andante – iii. Allegro – iv. Polonaise – v. Allegro, ma non troppo |

| 322 | 4 | A minor | 8 October 1739 | i. Larghetto affetuoso – ii. Allegro – iii. Largo, e piano – iv. Allegro |

| 323 | 5 | D major | 10 October 1739 | i. Ouverture – ii. Allegro – iii. Presto – iv. Largo – v. Allegro – vi. Menuet |

| 324 | 6 | G minor | 15 October 1739 | i. Larghetto e affetuoso – ii. Allegro, ma non troppo – iii. Musette – iv. Allegro – v. Allegro |

| 325 | 7 | B♭ major | 12 October 1739 | i. Largo – ii. Allegro – iii. Largo, e piano – iv. Andante – v. Hornpipe |

| 326 | 8 | C minor | 18 October 1739 | i. Allemande – ii. Grave – iii. Andante allegro – iv. Adagio – v. Siciliana – vi. Allegro |

| 327 | 9 | F major | 26 October 1739 (?) | i. Largo – ii. Allegro – iii. Larghetto – iv. Allegro – v. Menuet – vi. Gigue |

| 328 | 10 | D minor | 22 October 1739 | i. Ouverture – ii. Air – iii. Allegro – iv. Allegro – v. Allegro moderato |

| 329 | 11 | A major | 30 October 1739 | i. Andante larghetto, e staccato – ii. Allegro – iii. Largo, e staccato – iv. Andante – v. Allegro |

| 330 | 12 | B minor | 20 October 1739 | i. Largo – ii. Allegro – iii. Larghetto, e piano – iv. Largo – v. Allegro |

Borrowings

- No. 1 The first movement was a complete reworking of a first draft of the overture for Imeneo, Handel's penultimate Italian opera, composed over a prolonged period from 1738 to 1740. In an influential study, musicologist Alexander Silbiger argues that in the last movement, "beginning with the opening figure, there is a series of almost literal quotations from the Sonata no. 2" of the Essercizi Gravicembalo of Domenico Scarlatti, which had been published in London in 1738/39.[10]

- No. 2 Newly composed.

- No. 3 Newly composed.

- No. 4 Mostly newly composed. the final allegro is a reworking of the aria È si vaga in preparation for Imeneo.

- No. 5 Movements i, ii and vi are taken from the Ode for St Cecilia's Day. The first movement is derived from the Componimenti Musicali (1739) for harpsichord by Gottlieb Muffat and the fifth from the twenty third sonata in Domenico Scarlatti's Essercizi Gravicembalo (1738).

- No. 6 Newly composed.

- No. 7 Newly composed, except for the final hornpipe derived from Muffat's Componimenti Musicali.

- No. 8 The allemande is a reworking of the first movement of Handel's second harpsichord suite from his third set (No. 16), HWV 452, in G minor. Andrew Manze notes that its first bar "is a direct transposition of the opening bar of one of Johann Mattheson's Pièces de clavecin," and speculates "Perhaps, it is meant as a salute to an old friend, teacher and dueling partner"[11] The 4-note figure used in the third movement goes back to a quartet from Handel's opera Agrippina. In the fourth movement Handel quotes the opening ritornello of Cleopatra's aria Piangerò la sorte mia from the third act of his opera Giulio Cesare. In the fifth movement Handel uses material from the discarded aria "Love from such a parent born" from Saul.

- No. 9 The first movement was newly composed. The second and third movements are reworkings of the first two movements of the organ concerto in F major, HWV 295, "The Cuckoo and the Nightingale". The fourth and fifth movements are taken from the overture to Imeneo. The theme of the Gigue is "thematically reminiscent of the Giga in Arcangelo Corelli's Concerto Grosso No. 12" of the Twelve concerti grossi, Op. 6 (Corelli)" – the model for Handel's op. 6.[12]

- No. 10 Newly composed.

- No. 11 A reworking of Handel's organ concerto in A major, HWV 296. Handel borrowed the third-movement (Andante)'s melodic material from the opening of the Third Sonata of the Frische Clavier Früchte of Johann Kuhnau, published originally in 1696 but reprinted four other times, including in 1724.[13]

- No. 12 Mostly newly composed. The subject of the final fugue is derived from a fugue by Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, Handel's music teacher.

Musical structure

The analysis of individual movements is taken from Sadie (1972), Abraham (1954) and the notes by Hans Joachim Marx accompanying the recordings by Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert.

No. 1, HWV 319

The first short movement of the concerto starts dramatically, solemn and majestic: the orchestra ascends by degrees towards a more sustained section, each step in the ascent followed by a downward sighing figure first from the full orchestra, echoed by the solo violins. This severe grandeur elicits a gentle and eloquent response from the concertino string trio, in the manner of Corelli, with imitations and passages in thirds in the violins. The orchestra and soloists continue their dialogue until in the final ten bars, there is a reprise of the introductory music, now muted and in the minor key, ending with a remarkable chromatic passage of noble simplicity descending to the final drooping cadence.

The second movement is a lively allegro. The material is derived from the first two bars and a half bar figure that occurs in sequences and responses. Although it displays some elements of classical sonata form, the movement's success is due more to the unpredictable interchanges between orchestra and soloists.

The third movement is a dignified adagio, using similar anapaest figures to those in opening bars of the first movement. As Charles Burney wrote in 1785, "In the adagio, while the two trebles are singing in the style of vocal duets of the time, where these parts, though not in regular fugue, abound in imitations of the fugue kind; the base, with a boldness and character peculiar to Handel, supports with learning and ingenuity the subject of the two first bars, either direct or inverted, throughout the movement, in a clear, distinct and marked manner."

The fugal fourth movement has a catchy subject, first heard completely from the soloist. Despite being fugal in nature, it does not adhere to the strict rules of counterpoint, surprising the listener instead with ingenious episodes, alternating between the ripieno and concertino; at the close, where a bold restatement of the theme would be expected, Handel playfully curtails the movement with two pianissimo bars.

The last concerto-like movement is an energetic gigue in two parts, with the soloists echoing responses to the full orchestra.

No. 2, HWV 320

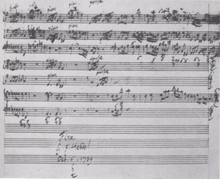

This four-movement concerto resembles a sonata da chiesa. From the original autograph, Handel initially intended the concerto to have two extra movements, a fugue in the minor key as second movement and a final gigue; these movements were later used elsewhere in the set.

The opening andante larghetto is noble, spacious and flowing, with rich harmonies. The responses from the concertino trio are derived from the opening ritornello. They alternate between a graceful legato and more decisive dotted rhythms. It has been suggested that the three unusual adagio cadences interrupted by pauses prior to the close indicate that Handel expected cadenzas by each of the soloists, although the surviving scores show no indication of this.

The second movement is an allegro in D minor in a contrapuntal trio sonata style. The animated semiquaver figure of the opening bars is played in imitation or in parallel thirds as a kind of moto perpetuo.

The third movement is unconventional. It alternates between two different moods: in the stately largo sections the full orchestra and solo violins respond in successive bars with incisive dotted rhythms; the larghetto, andante e piano at a slightly quicker speed in repeated quavers, is gentle and mysterious with harmonic complexity created by suspensions in the inner parts.

There is an apparent return to orthodoxy in the fourth movement which begins with a vigorous fugue in four parts, treated in a conventional manner. It is interrupted by contrasting interludes marked pianissimo in which a slow-moving theme, solemn and lyrical, is heard in the solo strings above repeated chords. This second theme is later revealed to be a counterpoint to the original fugal subject.

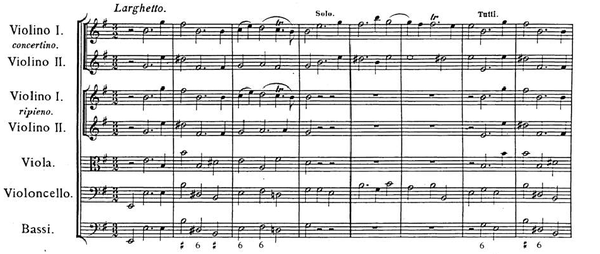

No. 3, HWV 321

In the opening larghetto in E minor the full orchestra three times plays the ritornello, a sarabande of serious gravity. The three concertino responses vere towards the major key, but only transitorily. The dialogue is resolved with the full orchestra combining the music from the ritornello and the solo interludes.

The profoundly tragic mood continues in the following andante, one of Handel's most personal statements. The movement is a fugue on a striking atonal four-note theme, B–G–D♯–C, which is reminiscent of Domenico Scarlatti's Cat fugue.[15] The suspensions and inner parts recall the contrapuntal writing of Bach. There is an unexpected addition of a G♯ in the last entry of the four-note theme in the bass as the movement draws to a close.

The third movement is an allegro. Of all the Op. 6, it comes the closest to Vivaldi's concerto writing, with its stern opening unison ritornello; however, despite a clear difference in texture between the solo violin sections and the orchestral tuttis, Handel breaks from the model by sharing material between both groups.

Although the charming and graceful fourth movement in G major is described as a polonaise, it has very few features in common with this popular eighteenth century dance form. The lower strings simulate a drone, creating a pastoral mood, but the dance-like writing for upper strings is more courtly than rustic.

The final short allegro, ma non troppo in 6

8 time brings the concerto back to E minor and a more serious mood, with chromaticism and unexpected key changes in the dialogue between concertino and ripieno.

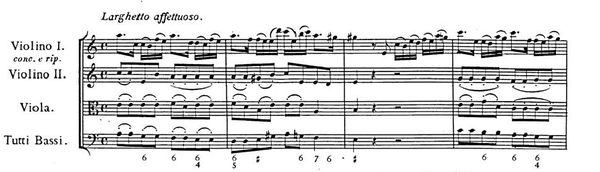

No. 4, HWV 322

The fourth concerto in A minor is a conventional orchestral concerto in four movements, with very little writing for solo strings, except for brief passages in the second and last movements.

The first movement, marked larghetto affetuoso, has been described as one of Handel's finest movements, broad and solemn. The melody is played by the first violins in unison, their falling appoggiatura semiquavers reflecting the galant style. Beneath them, the bass part moves steadily in quavers, with extra harmony provided by the inner parts.

The second allegro is an energetic fugue, the brief exchanges between concertino and ripieno strictly derived from the unusually long subject. The sombreness of the movement is underlined by the final cadence on the lowest strings of the violins and violas.

The largo e piano in F major is one of Handel's most sublime and simple slow movements, a sarabande in the Italian trio sonata style. Above a steady crotchet walking bass, the sustained theme is gently exchanged between the two violin parts, with imitations and suspensions; harmonic colour is added in the discreet viola part. In the closing bars the crotchet figure of the bass passes into the upper strings before the final cadence.

The last movement, an allegro in A minor, is a radical reworking of a soprano aria that Handel was preparing for his penultimate opera Imeneo. In the concerto, the material is more tightly argued, deriving from two fragmented highly rhythmic figures of 5 and 6 notes. Although there are unmistakable elements of wit in the imaginative development, the prevalent mood is serious: the sustained melodic interludes in the upper strings are tinged by unexpected flattened notes. In the coda, the first concertino violin restates the main theme, joined two bars later in thirds by the other solo violin and finally by repeated sustained pianissimo chords in the ripieno, modulating through unexpected keys. This is answered twice by two forte unison cadences, the second bringing the movement to a close.

No. 5, HWV 323

Charles Burney, 1785[16]

The fifth grand concerto in the brilliant key of D major is an energetic concerto in six movements. It incorporates in its first, second and sixth movements reworked versions of the three-movement overture to Handel's Ode for St Cecilia's Day HWV 76 (Larghetto, e staccato – allegro – minuet), composed in 1739 immediately prior to the Op. 6 concerti grossi and freely using Gottlieb Muffat's Componimenti musicali (1739) for much of its thematic material. The minuet was added later to the concerto grosso, perhaps for balance: it is not present in the original manuscript; the rejected trio from the overture was reworked at the same time for Op. 6 No. 3.

The first movement, in the style of a French overture with dotted rhythms and scale passages, for dramatic effect has the novel feature of being prefaced by a two bar passage for the first concertino violin.

The allegro, a vigorous and high-spirited fugue, differs very little from that in the Ode, except for three additional bars at the close. The composition, divided into easily discernible sections, relies more on harmony than counterpoint.

The third movement is a light-hearted presto in 3

8 time and binary form. A busy semiquaver figure runs through the dance-like piece, interrupted only by the cadences.

The largo in 3

2 time follows the pattern set by Corelli. The concertino parts dominate the movement, with the two solo violins in expressive counterpoint. Each episode for soloists is followed by a tutti response.

The delightful fifth allegro is written for full orchestra. The rollicking first subject is derived from the twenty third sonata in Domenico Scarlatti's Essercizi Gravicembalo of 1738. The subsequent repeated semiquaver passage-work over a walking bass recalls the style of Georg Philipp Telemann. Handel, however, treats the material in a wholly original way: the virtuoso movement is full of purpose with an unmistakable sense of direction, as the discords between the upper parts ineluctably resolve themselves.

The final menuet, marked un poco larghetto, is a more direct reworking of the minuet in the overture to the Ode. The first statement of the theme is melodically pruned down, so that the quaver figure in the response gives the impression of a variation. This warm-hearted and solid movement was added at a later stage by Handel, perhaps because it provided a more effective way to end the concerto than the brilliant fifth movement.

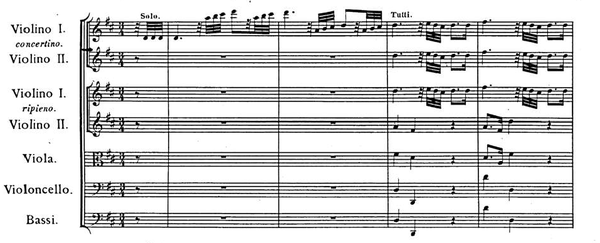

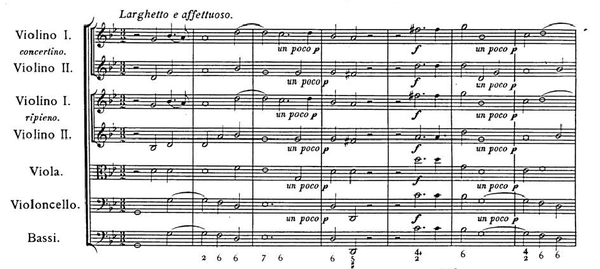

No. 6, HWV 324

The sixth concerto in G minor was originally intended to have four movements. The autograph manuscript contains the sketch for a gavotte in two parts, which, possibly in order to restore an imbalance created by the length of the musette and its different key (E♭ major), Handel abandoned in favour of two new shorter allegro movements. The musette thus became the central movement, with a return to the minor tonality in the concluding movements.

The first movement, marked Larghetto e affetuoso, is one of the darkest that Handel wrote, with a tragic pathos that easily equals that of the finest dramatic arias in his opera seria. Although inspired by the model of Corelli, it is far more developed and innovative in rhythm, harmony and musical texture. There are brief passages for solo strings which make expressive unembellished responses to the full orchestra. Despite momentary suggestions of modulations to the relative major key, the music sinks back towards the prevailing melancholic mood of G minor; at the sombre close, the strings descend to the lowest part of their register.

The second movement is a concise chromatic fugue, severe, angular and unrelenting, showing none of Handel's usual tendency to depart from orthodoxy.

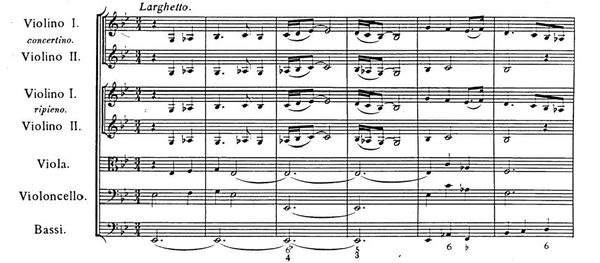

The elegiac musette in E♭ major is the crowning glory of the concerto, praised by the contemporary commentator Charles Burney, who described how Handel would often perform it as a separate piece during oratorios. In this highly original larghetto, Handel conjures up a long dreamy pastoral of some 163 bars. Like the similarly popular aria Son confusa pastorella from Act III of Handel's opera Poro re dell'Indie (1731), it was inspired by Telemann's Harmonischer Gottes Dienst.[17] The musette starts with a gravely beautiful main theme: Handel creates a unique dark texture of lower register strings over a drone bass, the traditional accompaniment for this dance, derived from the drone of the bagpipes. This sombre theme alternates with contrasting spirited episodes on the higher strings. The movement divides into four parts: first a statement of the theme from the full orchestra; then a continuation and extension of this material as a dialogue between concertino and ripieno strings, with the typical dotted rhythms of the musette; then a section for full orchestra in C minor with semiquaver passage-work for violins over the rhythms of the original theme in the lower strings; and finally a shortened version of the dialogue from the second section to conclude the work.

The following allegro is an energetic Italianate movement in the style of Vivaldi, with ritornello passages alternating with the virtuoso violin solo. It departs from its model in freely intermingling the solo and tutti passages after a central orchestral episode in D minor.

The final movement is a short dance-like allegro for full orchestra in 3

8 time and binary form, reminiscent of the keyboard sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti.

No. 7, HWV 325

The seventh concerto is the only one for full orchestra: it has no solo episodes and all the movements are brief.

The first movement is a largo, ten bars long, which like an overture leads into the allegro fugue on a single note, that only a composer of Handel's stature would have dared to attempt. The theme of the fugue consists of the same note for three bars (two minims, four crotchets, eight quavers) followed by a bar of quaver figures, which with slight variants are used as thematic material for the entire movement, a work relying primarily on rhythm.

The central expressive largo in G minor and 3

4 time, reminiscent of the style of Bach, is harmonically complex, with a chromatic theme and closely woven four-part writing.

The two final movements are a steady andante with recurring ritornellos and a lively hornpipe replete with unexpected syncopation

No. 8, HWV 326

The eighth concerto in C minor draws heavily on Handel's earlier compositions. Its form, partly experimental. is close to that of the Italian concerto da camera, a suite of dances. There are six movements of great diversity.

The opening allemande for full orchestra is a reworking of the first movement of Handel's second harpsichord suite from his third set (No. 16), HWV 452, in G minor.

The short grave in F minor, with unexpected modulations in the second section, is sombre and dramatic. It is a true concerto movement, with exchanges between soloists and orchestra.

The third andante allegro is original and experimental, taking a short four-note figure from Handel's opera Agrippina as a central motif. This phrase and a repeated quaver figure are passed freely between soloists and ripieno in a movement that relies on musical texture.

The following brief adagio, melancholy and expressive, would have been instantly recognized by Handel's audience as starting with a direct quotation from Cleopatra's aria Piangerò la sorte mia from Act III of his popular opera Giulio Cesare (1724).

The siciliana is similar in style to those Handel wrote for his operas, always marking moments of tragic pathos; one celebrated example is the soprano-alto duet Son nata a lagrimar for Sesto and Cornelia at the end of act 1 of Giulio Cesare. Its theme was already used in the aria "Love from such a parent born" for Michal from his oratorio Saul (eventually discarded by Handel) and recurs in the aria "Se d'amore amanti siete" for soprano and two alto recorders from Imeneo, each time in the same key of C minor.[18] The movement alternates passages for soloists and full orchestra. Some parts of the later thematic material seem like precursors of what Handel later used in Messiah in the pastoral symphony and in "He shall feed his flock". At the close, following a passage where the two solo violins play in elaborate counterpoint over a statement of the main theme in the full orchestra, Handel, in a stroke of inspiration, suddenly has a simple piano restatement of the theme in the concertino leading into two bars of bare and halting muted tutti chords, before a concluding reprise of the theme by the full orchestra.

The final allegro is a sort of polonaise in binary form for full orchestra. Its transparency and crispness result partly from the amalgamation of the second violin and viola parts into a single independent voice.

No. 9, HWV 327

The ninth concerto grosso is the only one that is undated in the original manuscript, probably because the last movement was discarded for one of the previously composed concertos. Apart from the first and last movements, it contains the least quantity of freshly composed material of all the concertos.

The opening largo consists of 28 bars of bare chords for full orchestra, with the interest provided by the harmonic progression and changes in the dynamic markings. Stanley Sadie has declared the movement an unsuccessful experiment, although others have pointed out that the music nevertheless holds the listener's attention, despite its starkness. Previous commentators have suggested that perhaps an extra improvised voice was intended by Handel, but such a demand on a soloist would have been beyond usual baroque performing practices.

The second and third movements are reworkings of the first two movements Handel's organ concerto in F major, HWV 295, often referred to as "The cuckoo and the nightingale", because of the imitation of birdsong. The allegro is skillfully transformed into a more disciplined and broader movement than the original, while retaining its innovative spirit. The solo and orchestral parts of the original are intermingled and redistributed in an imaginative and novel way between concertino and ripieno. The "cuckoo" effects are transformed into repeated notes, sometimes supplemented by extra phrases, exploiting the different sonorities of solo and tutti players. The "nightingale" effects are replaced by reprises of the ritornello and the modified cuckoo. The final organ solo, partly ad libitum, is replaced by virtuoso semiquaver passages and an extra section of repeated notes precedes the final tutti. The larghetto, a gentle siciliana, is similarly transformed. The first forty bars use the same material, but Handel makes a stronger conclusion with a brief return to the opening theme.

For the fourth and fifth movements, Handel used the second and third parts of the second version of the overture to his still unfinished opera Imeneo. Both movements were transposed from G to F: the allegro an animated but orthodox fugue; the minuet starting unusually in the minor key, but moving to the major key for the eight bar coda.

The final gigue in binary form was left over from Op. 6, No. 2, after Handel recomposed its closing movements.

No. 10, HWV 328

The tenth Grand Concerto in D minor has the form a baroque dance suite, introduced by a French overture: this accounts for the structure of the concerto and the presence of only one slow movement.

The first movement, marked ouverture – allegro – lentement, has the form a French overture. The dotted rhythms in the slow first part are similar to those Handel used in his operatic overtures. The subject of the allegro fugue in 6

8 time, two rhythmic bars leading into four bars in semiquavers, allowed him to make every restatement sound dramatic. The fugue leads into a short concluding lentement passage, a variant of the material from the start.

The Air, lentement is a sarabande-like dance movement of noble and monumental simplicity, its antique style enhanced by hints of modal harmonies.

The following two allegros are loosely based on the allemande and the courante. The scoring in the first allegro, in binary form, is similar in style to that of allemandes in baroque keyboard suites. The second allegro is a longer, ingeniously composed movement in the Italian concerto style. There is no ritornello; instead the rhythmic material in the opening bars and the first entry in the bass line is used in counterpoint throughout the piece to create a feeling of rhythmic direction, full of merriment and surprises.

The final allegro moderato in D major had originally been intended for the twelfth concerto, when Handel had experimented with the keys of D major and B minor. A cheerful gavotte-like movement, it is in binary form, with a variation (or double) featuring repeated semiquavers and quavers in the upper and lower strings.

No. 11, HWV 329

Charles Burney, 1785[19]

The eleventh concerto was probably the last to be completed according to the date in the autograph manuscript. Handel chose to make this concerto an adaptation of his recently composed but still unpublished organ concerto HWV 296 in A major: in either form it has been ranked as one of the very finest of Handel's concertos, "a monument of sanity and undemonstrative sense", according to Basil Lam.[20] The concerto grosso is more carefully worked out, with an independent viola part and modifications to accommodate the string soloists. The ad libitum sections for organ are replaced by accompanied passages for solo violin. The order of the third and fourth movements was reversed so that the long andante became the central movement in the concerto grosso.

The first two movements together have the form of a French overture. In the andante larghetto, e staccato the orchestral ritornellos with their dotted rhythms alternate with the virtuoso passages for upper strings and solo first violin. The following allegro is a short four-part fugue which concludes with the fugal subject replaced by an elaborated semiquaver version of the first two bars of the original subject. In the autograph score of the first of his organ concertos Op.7 in D minor, Handel indicated that a version of this movement should be played, shared between organ and string and transposed up a semitone into B♭ major.

An introductory six bar largo precedes the fourth movement, a long andante in Italian concerto form which forms the centre of the concerto. The ritornello theme, of deceptive simplicity and quintessentially Handelian, alternates with virtuosic gigue-like passages for solo strings, in each reprise the ritornello subtly transformed but still recognizable.

The final allegro is an ingenious instrumental version of a da capo aria, with a middle section in the relative minor key, F♯ minor. It incorporates the features of a Venetian conerto: the brilliant virtuosic episodes or solo violin alternate with the four-bar orchestral ritornello, which Handel varies on each reprise.

No. 12, HWV 330

Basil Lam, writing of the third movement in the last Grand Concerto[21]

The arresting dotted rhythms of the opening largo recall the dramatic style of the French overture, although the movement also serves to contrast the full orchestra with the quieter ripieno strings.

The following highly inventive movement is a brilliant and animated allegro, a moto perpetuo. The busy semiquaver figure in the theme, passed constantly between different parts of the orchestra and the soloists, only adds to the overall sense of rhythmic and harmonic direction. Although superficially in concerto form, this movement's success is probably more a result of Handel's departure from convention.

The central third movement, marked Larghetto e piano, contains one of the most beautiful melodies written by Handel. With its quiet gravity, it is similar to the andante larghetto, sometimes referred to as the "minuet", in the overture to the opera Berenice, which Charles Burney described as "one of the most graceful and pleasing movements that has ever been composed".[22] The melody in 3

4 time and E major is simple and regular with a wide range with a chaconne-like bass. After its statement, it is varied twice, the first time with a quaver walking bass, then with the melody itself played in quavers.

The fourth movement is a brief largo, like an accompanied recitative, which leads into the final allegro fugue. Its gigue-like theme is derived from a fugue of Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, Handel's boyhood teacher in Halle, to whom the movement is perhaps some form of homage.

Reception and influence

If the epithet grand, instead of implying, as it usually does, many parts, or a Concerto requiring a great band or Orchestra, had been here intended to express sublimity and dignity, it might have been used with the utmost propriety; for I can recollect no movement that is more lofty and noble than this; or in which the treble and the base of the tutti, or full parts, are of such distinct and marked characters; both bold, and contrasted, not only with each other, but with the solo parts, which are graceful and chantant. Nor did I ever know such business done in so short a time; that movement contains but thirty-four bars, and yet nothing seems left unsaid; and though it begins with so much pride and haughtiness, it melts at last into softness; and, where it modulates into a minor key, seems to express fatigue, languor and fainting.

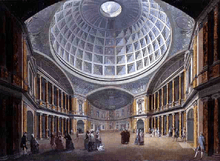

Handel's twelve grand concertos were already available to the public through Walsh's 1740 solo organ arrangements of four of them and through the various editions of the full Opus 6 produced during Handel's lifetime. Twenty-five years after Handel's death, a Handel Commemoration was initiated in London by George III in 1784, with five concerts in Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon. These concerts, repeated over the next few years and establishing an English tradition for Handel festivals in the nineteenth century and beyond, were on a grand scale, with huge choruses and instrumental forces, far beyond what Handel had at his disposal: apart from sackbuts and trombones, a special organ was installed in the Abbey with displaced keyboards. Nevertheless, excerpts from four of his grand concertos (Nos. 1, 5, 6 and 11), originally conceived for baroque chamber orchestra, were performed at the first commemoration; Op. 6, No. 1, was played in its entirety at the fourth concert in Westminster Abbey. They were described in detail by the contemporary musicologist and commentator Charles Burney in 1785.[25][26] Three years later Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart incorporated the Musette from Op. 6, No. 6, and a short Largo from Op. 6, No. 7, into his reorchestration of Acis and Galatea, K 566.[27]

Like Handel's organ concertos, in the nineteenth century his concerti grossi Op. 6 became widely available in versions for piano solo, piano duet and two pianos. Breitkopf and Härtel published two piano arrangements of four of the concertos by Gustav Krug (1803–1873). There are piano duet versions by August Horn (1839–1893), Salamon Jadassohn (1831–1902), Wilhelm Kempff, Richard Kleinmichel (1846–1941), Ernst Naumann (1832–1910), Adolf Rutthardt (1849–1934), F. L. Schubert (1804–1868) and Ludwig Stark (1831–1884). There also arrangements of several for piano solo by various composers, including Gustav Friedrich Kogel (1849–1921), Giuseppe Martucci (1856–1909), Otto Singer (1833–1894) and August Stradel (1860–1930), who arranged the whole set.[28]

In the twentieth century, Arnold Schoenberg, a composer openly antipathetic to Handel but at a turning point in his musical career, "freely arranged" the Concerto Grosso, Op. 6, No. 7, in his Concerto for string quartet and orchestra (1933). Schoenberg's compositional processes have been discussed in detail by Auner (1996), who also provides a facsimile of Schoenberg's heavily annotated copy of the original score.

Discography

- Boyd Neel (conductor), The Boyd Neel String Orchestra, London Records (1952)

- Herbert von Karajan (conductor and harpsichord, Nos. 1 & 10–12), Berliner Philharmoniker, 3 discs, Deutsche Grammophon (1966–1968)

- Sir Neville Marriner (conductor), Academy of St Martin in the Fields, 3 discs (Paired with Concerti grossi, Op. 3) Decca Records (1968)

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt (conductor), Concentus Musicus Wien, 3 discs, TELDEC (1982)

- Trevor Pinnock (conductor and harpsichord), The English Concert, 3 discs, Archiv Produktion (1987–1988)

- Christopher Hogwood (conductor and harpsichord), Handel and Haydn Society, 2 discs, Decca Records (1991–1992)

- Yuli Turovsky (conductor), I Musici de Montreal Chamber Orchestra, 3 discs, Chandos (1992)

- Andrew Manze (conductor and violin), Academy of Ancient Music, 2 discs, Harmonia Mundi (1998)

- Pavlo Beznosiuk (conductor and violin), The Avison Ensemble, 3 discs, Linn Records (2010)

See also

Notes

- Burney 2008, p. 54

- Sadie 1972, pp. 31–32

- Burrows 1997, p. 204

- Taylor 1987

- Maunder 2004, p. 113

- Sadie 1972

- Burrows 1997, pp. 205–206

- Sadie 1972, p. 39

- Hicks 1989

- Alexander Silberger, "Scarlatti Borrowings in Handel's Grand Concertos," The Musical Times, Vol. 125, No. 1692, February 1984, p. 93

- Andrew Manze, "Handel's Concerti Grossi, Op 6 Twelve Grand Concertos in Seven Parts," liner notes to Harmonia mundi HMU90728.29, 1998

- GFHandel.org, "G. F. Handel's Compositions HWV 301–400", URL="Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-08. Retrieved 2014-12-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- John Butt, liner notes to his recording Kuhnau, Harmonia mundi HMU 907097, 1992

- Mainwaring 1760, pp. 202–203

- Keefe 2005, p. 63

- Burney 2008, p. 57

- Dean, Winton (2006), Handel's Operas 1726–1741, The Boydell Press, p. 183, ISBN 1843832682

- Dean 2006, p. 458,470

- Burney 2008, p. 66–67

- Abraham 1954, p. 208

- Abraham 1954, p. 209

- Dean 2006, p. 388

- McGairl, Pamela (1986), "The Vauxhall Jubilee, 1786", The Musical Times, 127: 611–615, JSTOR 964270

- Burney 2008, p. 102

- Burney 2008

- Bicknell 1999

- Notes on Mozart's version of Acis and Galatea, by Julian Rushton

- Handel arrangements for piano

References

- Abraham, Gerald (1954), Handel: a symposium, Oxford University Press, pp. 200–209, "The Orchestral Music", Chapter 7 by Basil Lam

- Auner, Joseph H. (1996), "Schoenberg's Handel Concerto and the Ruins of Tradition", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 49: 264–313, doi:10.2307/831991, JSTOR 831991

- Bicknell, Stephen (1999), The History of the English Organ, Cambridge University Press, p. 173, ISBN 0521654092

- Burney, Charles (2008), An Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster Abbey, and the Pantheon, May 26, 27, 29 and June 3, 5, 1784, in Commemoration of Handel, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1436767415, originally published by the University of Oxford in 1785

- Burrows, Donald (1997), The Cambridge Companion to Handel, Cambridge Companions to Music, Cambridge University Press, pp. 193–207, ISBN 0521456134, "Handel as concerto composer", Chapter 13 by Donald Burrows

- Hicks, Anthony (1989), "Hill and Handel", The Musical Times, 130: 196–197, JSTOR 966459

- Keefe, Simon P. (2005), The Cambridge Companion to the Concerto, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 052183483X

- Mainwaring, John (1760), Memoirs of the life of the late George Frederic Handel, R. & J. Dodsley, JSTOR 964195

- Maunder, Richard (2004), The Scoring of Baroque Concertos, Boydell Press, ISBN 9781843830719

- Sadie, Stanley (1972), Handel Concertos, BBC Music Guides, BBC, pp. 36–55, ISBN 0563103493

- Taylor, Carole (1987), Handel's Disengagement from the Italian Opera, Handel: tercentenary collection (eds. Stanley Sadie and Anthony Hicks), University of Rochester Press, pp. 165–181, ISBN 0835718336

Further reading

- Derr, Ellwood (1989), "Handel's use of Scarlatti's "Essercizi per Gravicambelo" in his Opus 6", Göttinger-Händel-Beiträge, Bärenreiter, 3: 170–187

- Kloiber, Rudolf (1972), Handbuch des Instrumentalkonzerts, Volume 1, Breitkopf and Härtel, pp. 104–126

- Mann, Alfred (1996), Handel, the orchestral music, Monuments of Western music, Schirmer Books, ISBN 0028713826

- Redlich, Hans; Hoffman, Adolf (1961), Twelve concerti grossi Op. 6, Hallische Händel-Ausgabe, IV/14, Bärenreiter

- Redlich, Hans F. (1968), "The Oboes in Handel's Op 6", The Musical Times, 109: 530–531, JSTOR 952543

- Silbiger, Alexander (1984), "Scarlatti Borrowings in Handel's Grand Concertos", The Musical Times, 125: 93–95

- Van Til, Marian (2007), George Frideric Handel: A Music Lover's Guide to His Life, His Faith & the Development of Messiah and His Other Oratorios, WordPower Publishing, ISBN 0979478502

External links

- Grand Concertos Op. 6, Walsh's 1740 keyboard arrangements of Op. 6 Nos. 1, 5, 6 and 10: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Video recording of HWV 319/i,ii,iii and HWV 319/iv,v, live performance by Le Musiche Da Camera in Santa Caterina a Chiaia, Naples

- Video recording of HWV 319 on YouTube, live performance by the Georgian Sinfonietta conducted by David Kintsurashvili

- Animated midi recording of HWV 320/i,ii,iii,iv

- Video recording of HWV 321/i,ii,iii and HWV 321/iv,v, live performance by the Orchestra Sinfonica di Terni conducted by Paolo Venturi

- Animated midi recording of HWV 322/i<,ii,iii,iv

- Video recording of HWV 323 on YouTube, live performance with the Belarusian National Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Igor Bukhvalov

- Animated midi recording of HWV 324/i,ii,iii,iv,v

- Video recording of HWV 325 on YouTube, live performance from the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam with the Combattimento Consort directed by Jan Willem de Vriend

- Audio recording of HWV 326/iv,v on YouTube, live performance by the Burlington Chamber Orchestra directed by Michael Hopkins

- Animated midi recording of HWV 327/i,ii,iii,iv,v,vi

- Animated midi recording of HWV 328/i,ii,iii,iv,v,vi

- Performance of HWV 329 by A Far Cry from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in MP3 format

- Video recording of HWV 330/ii on YouTube, Kiev Chamber Orchestra with violin soloists Vadym Borysov and Yulia Rubanova

- Video recording of HWV 330/ii on YouTube, The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra directed by Paul Dyer

- Animated midi recording of HWV 330/i–v, alternative version of HWV 330/iii, Aria: larghetto e piano