Compressibility

In thermodynamics and fluid mechanics, compressibility (also known as the coefficient of compressibility[1] or isothermal compressibility[2]) is a measure of the relative volume change of a fluid or solid as a response to a pressure (or mean stress) change. In its simple form, the compressibility β may be expressed as

- ,

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

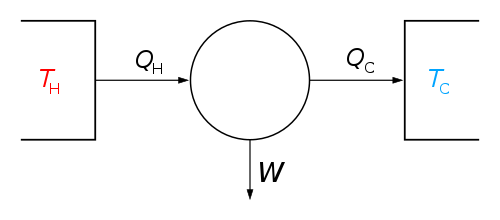

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

where V is volume and p is pressure. The choice to define compressibility as the negative of the fraction makes compressibility positive in the (usual) case that an increase in pressure induces a reduction in volume.

Definition

The specification above is incomplete, because for any object or system the magnitude of the compressibility depends strongly on whether the process is isentropic or isothermal. Accordingly, isothermal compressibility is defined:

where the subscript T indicates that the partial differential is to be taken at constant temperature.

Isentropic compressibility is defined:

where S is entropy. For a solid, the distinction between the two is usually negligible.

Relation to speed of sound

The speed of sound is defined in classical mechanics as:

where ρ is the density of the material. It follows, by replacing partial derivatives, that the isentropic compressibility can be expressed as:

Relation to bulk modulus

The inverse of the compressibility is called the bulk modulus, often denoted K (sometimes B). The compressibility equation relates the isothermal compressibility (and indirectly the pressure) to the structure of the liquid.

Thermodynamics

The term "compressibility" is also used in thermodynamics to describe the deviance in the thermodynamic properties of a real gas from those expected from an ideal gas. The compressibility factor is defined as

where p is the pressure of the gas, T is its temperature, and V is its molar volume. In the case of an ideal gas, the compressibility factor Z is equal to unity, and the familiar ideal gas law is recovered:

Z can, in general, be either greater or less than unity for a real gas.

The deviation from ideal gas behavior tends to become particularly significant (or, equivalently, the compressibility factor strays far from unity) near the critical point, or in the case of high pressure or low temperature. In these cases, a generalized compressibility chart or an alternative equation of state better suited to the problem must be utilized to produce accurate results.

A related situation occurs in hypersonic aerodynamics, where dissociation causes an increase in the “notional” molar volume, because a mole of oxygen, as O2, becomes 2 moles of monatomic oxygen and N2 similarly dissociates to 2 N. Since this occurs dynamically as air flows over the aerospace object, it is convenient to alter Z, defined for an initial 30 gram moles of air, rather than track the varying mean molecular weight, millisecond by millisecond. This pressure dependent transition occurs for atmospheric oxygen in the 2,500–4,000 K temperature range, and in the 5,000–10,000 K range for nitrogen.[3]

In transition regions, where this pressure dependent dissociation is incomplete, both beta (the volume/pressure differential ratio) and the differential, constant pressure heat capacity greatly increases.

For moderate pressures, above 10,000 K the gas further dissociates into free electrons and ions. Z for the resulting plasma can similarly be computed for a mole of initial air, producing values between 2 and 4 for partially or singly ionized gas. Each dissociation absorbs a great deal of energy in a reversible process and this greatly reduces the thermodynamic temperature of hypersonic gas decelerated near the aerospace object. Ions or free radicals transported to the object surface by diffusion may release this extra (nonthermal) energy if the surface catalyzes the slower recombination process.

The isothermal compressibility is generally related to the isentropic (or adiabatic) compressibility by a few relations:[4]

where γ is the heat capacity ratio, α is the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion, ρ = N/V is the particle density, and is the thermal pressure coefficient.

In an extensive thermodynamic system, the isothermal compressibility is also related to the relative size of fluctuations in particle density:[4]

where μ is the chemical potential.

Compressibility of ionic liquids and molten salts can be expressed as a sum of the contribution of the ionic lattice and of the holes.

Earth science

| Material | β (m2/N or Pa−1) |

|---|---|

| Plastic clay | 2×10−6 – 2.6×10−7 |

| Stiff clay | 2.6×10−7 – 1.3×10−7 |

| Medium-hard clay | 1.3×10−7 – 6.9×10−8 |

| Loose sand | 1×10−7 – 5.2×10−8 |

| Dense sand | 2×10−8 – 1.3×10−8 |

| Dense, sandy gravel | 1×10−8 – 5.2×10−9 |

| Ethyl alcohol[6] | 1.1×10−9 |

| Carbon disulfide[6] | 9.3×10−10 |

| Rock, fissured | 6.9×10−10 – 3.3×10−10 |

| Water at 25 °C (undrained)[7] | 4.6×10–10 |

| Rock, sound | < 3.3×10−10 |

| Glycerine[6] | 2.1×10−10 |

| Mercury[6] | 3.7×10−11 |

The Earth sciences use compressibility to quantify the ability of a soil or rock to reduce in volume under applied pressure. This concept is important for specific storage, when estimating groundwater reserves in confined aquifers. Geologic materials are made up of two portions: solids and voids (or same as porosity). The void space can be full of liquid or gas. Geologic materials reduce in volume only when the void spaces are reduced, which expel the liquid or gas from the voids. This can happen over a period of time, resulting in settlement.

It is an important concept in geotechnical engineering in the design of certain structural foundations. For example, the construction of high-rise structures over underlying layers of highly compressible bay mud poses a considerable design constraint, and often leads to use of driven piles or other innovative techniques.

Fluid dynamics

The degree of compressibility of a fluid has strong implications for its dynamics. Most notably, the propagation of sound is dependent on the compressibility of the medium.

Aerodynamics

Compressibility is an important factor in aerodynamics. At low speeds, the compressibility of air is not significant in relation to aircraft design, but as the airflow nears and exceeds the speed of sound, a host of new aerodynamic effects become important in the design of aircraft. These effects, often several of them at a time, made it very difficult for World War II era aircraft to reach speeds much beyond 800 km/h (500 mph).

Many effects are often mentioned in conjunction with the term "compressibility", but regularly have little to do with the compressible nature of air. From a strictly aerodynamic point of view, the term should refer only to those side-effects arising as a result of the changes in airflow from an incompressible fluid (similar in effect to water) to a compressible fluid (acting as a gas) as the speed of sound is approached. There are two effects in particular, wave drag and critical mach.

Negative compressibility

In general, the bulk compressibility (sum of the linear compressibilities on the three axes) is positive, that is, an increase in pressure squeezes the material to a smaller volume. This condition is required for mechanical stability.[8] However, under very specific conditions the compressibility can be negative.[9]

See also

- Mach number

- Mach tuck

- Poisson ratio

- Prandtl–Glauert singularity, associated with supersonic flight

- Shear strength

References

- "Coefficient of compressibility - AMS Glossary". Glossary.AMetSoc.org. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Isothermal compressibility of gases -". Petrowiki.org. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- Regan, Frank J. (1993). Dynamics of Atmospheric Re-entry. p. 313. ISBN 1-56347-048-9.

- Landau; Lifshitz (1980). Course of Theoretical Physics Vol 5: Statistical Physics. Pergamon. pp. 54-55 and 342.

- Domenico, P. A.; Mifflin, M. D. (1965). "Water from low permeability sediments and land subsidence". Water Resources Research. 1 (4): 563–576. Bibcode:1965WRR.....1..563D. doi:10.1029/WR001i004p00563. OSTI 5917760.

- Hugh D. Young; Roger A. Freedman. University Physics with Modern Physics. Addison-Wesley; 2012. ISBN 978-0-321-69686-1. p. 356.

- Fine, Rana A.; Millero, F. J. (1973). "Compressibility of water as a function of temperature and pressure". Journal of Chemical Physics. 59 (10): 5529–5536. Bibcode:1973JChPh..59.5529F. doi:10.1063/1.1679903.

- Munn, R. W. (1971). "Role of the elastic constants in negative thermal expansion of axial solids". Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 5 (5): 535–542. Bibcode:1972JPhC....5..535M. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/5/5/005.

- Lakes, Rod; Wojciechowski, K. W. (2008). "Negative compressibility, negative Poisson's ratio, and stability". Physica Status Solidi B. 245 (3): 545. Bibcode:2008PSSBR.245..545L. doi:10.1002/pssb.200777708.

Gatt, Ruben; Grima, Joseph N. (2008). "Negative compressibility". Physica Status Solidi RRL. 2 (5): 236. Bibcode:2008PSSRR...2..236G. doi:10.1002/pssr.200802101.

Kornblatt, J. A. (1998). "Materials with Negative Compressibilities". Science. 281 (5374): 143a–143. Bibcode:1998Sci...281..143K. doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.143a.

Moore, B.; Jaglinski, T.; Stone, D. S.; Lakes, R. S. (2006). "Negative incremental bulk modulus in foams". Philosophical Magazine Letters. 86 (10): 651. Bibcode:2006PMagL..86..651M. doi:10.1080/09500830600957340.