Measure (mathematics)

In mathematical analysis, a measure on a set is a systematic way to assign a number to each suitable subset of that set, intuitively interpreted as its size. In this sense, a measure is a generalization of the concepts of length, area, and volume. A particularly important example is the Lebesgue measure on a Euclidean space, which assigns the conventional length, area, and volume of Euclidean geometry to suitable subsets of the n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn. For instance, the Lebesgue measure of the interval [0, 1] in the real numbers is its length in the everyday sense of the word, specifically, 1.

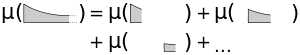

Technically, a measure is a function that assigns a non-negative real number or +∞ to (certain) subsets of a set X (see Definition below). It must further be countably additive: the measure of a 'large' subset that can be decomposed into a finite (or countably infinite) number of 'smaller' disjoint subsets is equal to the sum of the measures of the "smaller" subsets. In general, if one wants to associate a consistent size to each subset of a given set while satisfying the other axioms of a measure, one only finds trivial examples like the counting measure. This problem was resolved by defining measure only on a sub-collection of all subsets; the so-called measurable subsets, which are required to form a σ-algebra. This means that countable unions, countable intersections and complements of measurable subsets are measurable. Non-measurable sets in a Euclidean space, on which the Lebesgue measure cannot be defined consistently, are necessarily complicated in the sense of being badly mixed up with their complement.[1] Indeed, their existence is a non-trivial consequence of the axiom of choice.

Measure theory was developed in successive stages during the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Émile Borel, Henri Lebesgue, Johann Radon, and Maurice Fréchet, among others. The main applications of measures are in the foundations of the Lebesgue integral, in Andrey Kolmogorov's axiomatisation of probability theory and in ergodic theory. In integration theory, specifying a measure allows one to define integrals on spaces more general than subsets of Euclidean space; moreover, the integral with respect to the Lebesgue measure on Euclidean spaces is more general and has a richer theory than its predecessor, the Riemann integral. Probability theory considers measures that assign to the whole set the size 1, and considers measurable subsets to be events whose probability is given by the measure. Ergodic theory considers measures that are invariant under, or arise naturally from, a dynamical system.

Definition

Let X be a set and Σ a σ-algebra over X. A function μ from Σ to the extended real number line is called a measure if it satisfies the following properties:

- Non-negativity: For all E in Σ, we have μ(E) ≥ 0.

- Null empty set: .

- Countable additivity (or σ-additivity): For all countable collections of pairwise disjoint sets in Σ,

If at least one set has finite measure, then the requirement that is met automatically. Indeed, by countable additivity,

and therefore

If only the second and third conditions of the definition of measure above are met, and μ takes on at most one of the values ±∞, then μ is called a signed measure.

The pair (X, Σ) is called a measurable space, the members of Σ are called measurable sets. If and are two measurable spaces, then a function is called measurable if for every Y-measurable set , the inverse image is X-measurable – i.e.: . In this setup, the composition of measurable functions is measurable, making the measurable spaces and measurable functions a category, with the measurable spaces as objects and the set of measurable functions as arrows. See also Measurable function#Term usage variations about another setup.

A triple (X, Σ, μ) is called a measure space. A probability measure is a measure with total measure one – i.e. μ(X) = 1. A probability space is a measure space with a probability measure.

For measure spaces that are also topological spaces various compatibility conditions can be placed for the measure and the topology. Most measures met in practice in analysis (and in many cases also in probability theory) are Radon measures. Radon measures have an alternative definition in terms of linear functionals on the locally convex space of continuous functions with compact support. This approach is taken by Bourbaki (2004) and a number of other sources. For more details, see the article on Radon measures.

Examples

Some important measures are listed here.

- The counting measure is defined by μ(S) = number of elements in S.

- The Lebesgue measure on R is a complete translation-invariant measure on a σ-algebra containing the intervals in R such that μ([0, 1]) = 1; and every other measure with these properties extends Lebesgue measure.

- Circular angle measure is invariant under rotation, and hyperbolic angle measure is invariant under squeeze mapping.

- The Haar measure for a locally compact topological group is a generalization of the Lebesgue measure (and also of counting measure and circular angle measure) and has similar uniqueness properties.

- The Hausdorff measure is a generalization of the Lebesgue measure to sets with non-integer dimension, in particular, fractal sets.

- Every probability space gives rise to a measure which takes the value 1 on the whole space (and therefore takes all its values in the unit interval [0, 1]). Such a measure is called a probability measure. See probability axioms.

- The Dirac measure δa (cf. Dirac delta function) is given by δa(S) = χS(a), where χS is the indicator function of S. The measure of a set is 1 if it contains the point a and 0 otherwise.

Other 'named' measures used in various theories include: Borel measure, Jordan measure, ergodic measure, Euler measure, Gaussian measure, Baire measure, Radon measure, Young measure, and Loeb measure.

In physics an example of a measure is spatial distribution of mass (see e.g., gravity potential), or another non-negative extensive property, conserved (see conservation law for a list of these) or not. Negative values lead to signed measures, see "generalizations" below.

- Liouville measure, known also as the natural volume form on a symplectic manifold, is useful in classical statistical and Hamiltonian mechanics.

- Gibbs measure is widely used in statistical mechanics, often under the name canonical ensemble.

Basic properties

Let μ be a measure.

Monotonicity

If E1 and E2 are measurable sets with E1 ⊆ E2 then

Measure of countable unions and intersections

Subadditivity

For any countable sequence E1, E2, E3, ... of (not necessarily disjoint) measurable sets En in Σ:

Continuity from below

If E1, E2, E3, ... are measurable sets and for all n, then the union of the sets En is measurable, and

Continuity from above

If E1, E2, E3, ... are measurable sets and, for all n, then the intersection of the sets En is measurable; furthermore, if at least one of the En has finite measure, then

This property is false without the assumption that at least one of the En has finite measure. For instance, for each n ∈ N, let En = [n, ∞) ⊂ R, which all have infinite Lebesgue measure, but the intersection is empty.

Sigma-finite measures

A measure space (X, Σ, μ) is called finite if μ(X) is a finite real number (rather than ∞). Nonzero finite measures are analogous to probability measures in the sense that any finite measure μ is proportional to the probability measure . A measure μ is called σ-finite if X can be decomposed into a countable union of measurable sets of finite measure. Analogously, a set in a measure space is said to have a σ-finite measure if it is a countable union of sets with finite measure.

For example, the real numbers with the standard Lebesgue measure are σ-finite but not finite. Consider the closed intervals [k, k+1] for all integers k; there are countably many such intervals, each has measure 1, and their union is the entire real line. Alternatively, consider the real numbers with the counting measure, which assigns to each finite set of reals the number of points in the set. This measure space is not σ-finite, because every set with finite measure contains only finitely many points, and it would take uncountably many such sets to cover the entire real line. The σ-finite measure spaces have some very convenient properties; σ-finiteness can be compared in this respect to the Lindelöf property of topological spaces. They can be also thought of as a vague generalization of the idea that a measure space may have 'uncountable measure'.

s-finite measures

A measure is said to be s-finite if it is a countable sum of bounded measures. S-finite measures are more general than sigma-finite ones and have applications in the theory of stochastic processes.

Completeness

A measurable set X is called a null set if μ(X) = 0. A subset of a null set is called a negligible set. A negligible set need not be measurable, but every measurable negligible set is automatically a null set. A measure is called complete if every negligible set is measurable.

A measure can be extended to a complete one by considering the σ-algebra of subsets Y which differ by a negligible set from a measurable set X, that is, such that the symmetric difference of X and Y is contained in a null set. One defines μ(Y) to equal μ(X).

Additivity

Measures are required to be countably additive. However, the condition can be strengthened as follows. For any set and any set of nonnegative define:

That is, we define the sum of the to be the supremum of all the sums of finitely many of them.

A measure on is -additive if for any and any family of disjoint sets the following hold:

Note that the second condition is equivalent to the statement that the ideal of null sets is -complete.

Non-measurable sets

If the axiom of choice is assumed to be true, it can be proved that not all subsets of Euclidean space are Lebesgue measurable; examples of such sets include the Vitali set, and the non-measurable sets postulated by the Hausdorff paradox and the Banach–Tarski paradox.

Generalizations

For certain purposes, it is useful to have a "measure" whose values are not restricted to the non-negative reals or infinity. For instance, a countably additive set function with values in the (signed) real numbers is called a signed measure, while such a function with values in the complex numbers is called a complex measure. Measures that take values in Banach spaces have been studied extensively.[2] A measure that takes values in the set of self-adjoint projections on a Hilbert space is called a projection-valued measure; these are used in functional analysis for the spectral theorem. When it is necessary to distinguish the usual measures which take non-negative values from generalizations, the term positive measure is used. Positive measures are closed under conical combination but not general linear combination, while signed measures are the linear closure of positive measures.

Another generalization is the finitely additive measure, also known as a content. This is the same as a measure except that instead of requiring countable additivity we require only finite additivity. Historically, this definition was used first. It turns out that in general, finitely additive measures are connected with notions such as Banach limits, the dual of L∞ and the Stone–Čech compactification. All these are linked in one way or another to the axiom of choice. Contents remain useful in certain technical problems in geometric measure theory; this is the theory of Banach measures.

A charge is a generalization in both directions: it is a finitely additive, signed measure.

See also

- Abelian von Neumann algebra

- Almost everywhere

- Carathéodory's extension theorem

- Content (measure theory)

- Fubini's theorem

- Fatou's lemma

- Fuzzy measure theory

- Geometric measure theory

- Hausdorff measure

- Inner measure

- Lebesgue integration

- Lebesgue measure

- Lorentz space

- Lifting theory

- Measurable cardinal

- Measurable function

- Minkowski content

- Outer measure

- Product measure

- Pushforward measure

- Regular measure

- Vector measure

- Valuation (measure theory)

- Volume form

References

- Halmos, Paul (1950), Measure theory, Van Nostrand and Co.

- Rao, M. M. (2012), Random and Vector Measures, Series on Multivariate Analysis, 9, World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-4350-81-5, MR 2840012.

Bibliography

- Robert G. Bartle (1995) The Elements of Integration and Lebesgue Measure, Wiley Interscience.

- Bauer, H. (2001), Measure and Integration Theory, Berlin: de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110167191

- Bear, H.S. (2001), A Primer of Lebesgue Integration, San Diego: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0120839711

- Bogachev, V. I. (2006), Measure theory, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-3540345138

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (2004), Integration I, Springer Verlag, ISBN 3-540-41129-1 Chapter III.

- R. M. Dudley, 2002. Real Analysis and Probability. Cambridge University Press.

- Folland, Gerald B. (1999), Real Analysis: Modern Techniques and Their Applications, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0471317160 Second edition.

- Federer, Herbert. Geometric measure theory. Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, Band 153 Springer-Verlag New York Inc., New York 1969 xiv+676 pp.

- D. H. Fremlin, 2000. Measure Theory. Torres Fremlin.

- Jech, Thomas (2003), Set Theory: The Third Millennium Edition, Revised and Expanded, Springer Verlag, ISBN 3-540-44085-2

- R. Duncan Luce and Louis Narens (1987). "measurement, theory of," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 428–32.

- M. E. Munroe, 1953. Introduction to Measure and Integration. Addison Wesley.

- K. P. S. Bhaskara Rao and M. Bhaskara Rao (1983), Theory of Charges: A Study of Finitely Additive Measures, London: Academic Press, pp. x + 315, ISBN 0-12-095780-9

- Shilov, G. E., and Gurevich, B. L., 1978. Integral, Measure, and Derivative: A Unified Approach, Richard A. Silverman, trans. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-63519-8. Emphasizes the Daniell integral.

- Teschl, Gerald, Topics in Real and Functional Analysis, (lecture notes)

- Tao, Terence (2011). An Introduction to Measure Theory. Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 9780821869192.

- Weaver, Nik (2013). Measure Theory and Functional Analysis. World Scientific. ISBN 9789814508568.

External links

| Look up measurable in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.svg.png)