Cintra Bay

Cintra Bay or the Gulf of Cintra is a large, half-moon shaped[1] bay on the coast of Río de Oro province, Western Sahara. It is located about 120 km (75 mi) south of Dakhla. Its coastline is sparsely populated, and the environment is mostly wild and undeveloped. Originally called "St. Cyprian’s Bay", it was renamed after Gonçalo de Sintra, a 15th-century Portuguese explorer and slave raider.

| Cintra Bay | |

|---|---|

| Gulf of Cintra Golfo de Cintra | |

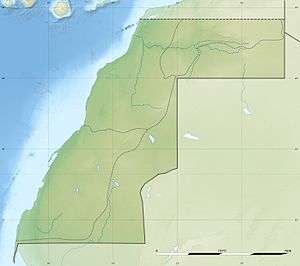

Cintra Bay Location off of Western Sahara | |

| Location | Western Sahara |

| Coordinates | 22.951944°N 16.215556°W |

| Type | Bay |

| Native name | Bahía de Cintra (Spanish) |

| Part of | Atlantic Ocean |

Etymology

The area was originally called "St. Cyprian’s Bay" but was renamed after Gonçalo de Sintra.[2]

The Treaty of Angra de Cintra of 1958, which led to the end of the War of Ifni, was named after Cintra Bay.

Geography

The bay occupies 29 nautical miles between Punta del Pescador and Lagouira bay, and in general is open and very shallow, the average depth of the central part being 10 meters.[3][4][4] It is about 24 km (15 mi) in diameter, from the northern cape of Puntilla de las Raimas, near Via Candelaria and Hassi Amatai, south to Puntila Negra or Punta Negra, near Las Talaitas.[5] The deepest point of the bay is at Hasi el Beied, near the middle of Cintra Bay. Gulf waters consist of the inner Angra de Citra and outer areas of Bajo El Tortugo, Bajo Ahogado, and Bajo del Medio Golfo. The pelagic water out of Cintra Bay is called Bajo Arcila. Cliffs, dunes, beaches, and lagoons make up most of the coastal landscape. A large lagoon, Bajo Tortugo ("Bay of the Little Tortoise"), is on the northern side, and there is an area named Las Matorrales in the southern part. Several hills, some of which have flattened top or peaks can be seen along the region.

Cintra Bay has a peninsula at each end. Punta de las Raimas in the north is 2 mi (3.2 km) in length and mostly sandy and has rocks and a reef at the tip, while a sand dune can be found on the Punta Negra, which has reefs extending about 2 mi (3.2 km) around it.[4]

The shoal off to the southwest of Cintra Bay is called Banco de Sylvia. It lies between Dakhla and Cintra Bay, while Amseisat Saccum and Imlili are further east within the inner desert.

Across the opposite side of Las Taraitas and Morro de Gorrei lies the Bay of Gorrei or the'Bahia de Gorrei, similar in shape but smaller than Cintra Bay. There are several other bays or inlets in shapes almost identical to Cintra or Gorrei Bays along the Rio de Oro region.

Bathymetry

The geographical and bathymetric factors of Cintra Bay make it suitable for fishing and aquaculture.[4] Its shallowness and closed-in aspect give it the highest water temperatures in the region. The south-north current flows only within the bay and is affected by tides, notably in areas near open water. This current also causes a vortex, or marine circulation in levorotation, at the northern area.[4]

Natural history

The bay's coastline and surrounding areas are part of the western Sahara Desert, being covered mostly by dunes, making Cintra bay's vegetation very poor.

In contrast to the land, the waters in this area are part of the Canary Current System which is a highly productive ocean current, and the Nouadhibou Upwelling. One of major upwelling zones is located just off the continental shelf. This makes the area one of the richest grounds for fishing in the world, and Cintra Bay itself serves as a spawning ground for sardines.[6] Cephalaspidea can also be found within the bay.[7]

It has been claimed that both the environment and biodiversity of Cintra Bay are threatened by an ongoing plan to strengthen Morocco's aquaculture with support from the EU,[8][9][4][10] and that research is needed in the area, notably on right whales,[11] and protections for local fishing communities.[12]

Marine mammals

Cetaceans

Based on 19th century whaling records, the coastline from 10 miles north of Puntilla de las Raimas, called "Goree" Bay by whalers, to 20 miles north of Cabo Barbas and possibly a broader range[13] was the only known wintering or calving ground for the eastern North Atlantic population of North Atlantic right whales.[14] These whales are now thought to be either extinct or in the low-tens of animals left at best.[15] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Cintra Bay Ground was one of three or four major grounds for right whale hunting in the North Atlantic, along with the south-eastern coastal United States, Cape Farewell in Greenland, and probably the Icelandic region, and also being one of two winter-spring fields along with the US coasts.[16]

Approximately 92 whales were killed during 44 visits by whalers from November to April each year, giving this region the highest catch density in the 19th century, though whaling was not carried out during all seasons. 82 of those animals were actually taken in the first two years of 1855-56, probably with some other species such as the humpbacks. A scientific survey extending to Dakhla peninsula/bay was conducted in 1998 and no evidence of any right whales still using the area was found.[17] It was also found that these coastal waters were surprisingly poor in cetacean biodiversity. Only two species were found regularly, both with very small numbers, and both were found only in the Dakhla Bay region: a larger type of bottlenose dolphin and Atlantic humpback dolphins. Killer whales are known to occur along the coasts of Western Sahara today[18] and occasionally in large numbers, according to whaling logs.

Recent studies gave hope that Cinta Bay could possibly be recolonized by right whales from the western population, as the two populations have been revealed to be much closer to each other than was previously thought.[19]

Regardless of habitat densities, baleen whales, fin whales, Brydes's whale, sei whales, and minke whales are known to still occur along the coasts of Western Sahara. Of these, fin whales and Bryde's whales had been confirmed in Dakhla and Cintra - Gorrei areas. Other species such as Risso's dolphins,[20] common dolphins, rough-toothed dolphins, and harbor porpoises [21] that have been confirmed in Bay of Arguin area may possibly occur here as well.[22][23] [24]

Pinnipeds

Along with cetaceans, Cintra Bay may provide an important habitat for critically endangered Mediterranean monk seals.[25][26] They were severely hunted to the brink of extinction in the 15th century by European sealers and local tribes, and are now almost extinct in the Mediterranean Sea. Though not in Cintra Bay, Cabo Blanco on Dakhla Peninsula still hosts the largest of the remaining colonies.[27]

Sea reptiles

Sea turtles are known to nest on the beach along the bay.[25] There have been studies focusing on Dakhla region.[28]

Birds

Many species of migratory birds and oceanic birds, such as Western Palearctic waders, winter on West Sahara´s coastline, in the Cintra Bay region and the Banc d'Arguin National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Mauritania where nearly 110 species of seabirds are confirmed.[29][30] Based on bio-tracking studies, osprey is also a species to migrate here.[31]

Settlements

The area is very remote and almost unpopulated, with only several small fishing settlements of shacks scattered along the coast. Of these, Puntillas de las Raimas which is at Bajo Tortugo, the northern end of the bay, is the largest. However, the population has reduced in recent times and the village was almost abandoned as of 2012.[20] Porto Rico, another fishing settlement in the north of the bay, also lost significant population.[33]

The closest urban city is at Dakhla, approximately 120 km (75 mi) away.

Tourism

Although Cintra Bay has been considered a local attraction, sandstorms (especially in the spring) and mines collected from Cabo Barbas make the area unsuitable for tourists.[34]

See also

References

- Burkhalter M. (2011). "Cintra Bay West Sahara". p. Panoramio. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- S, Chris (27 March 2016). "'V' is for Vintage Sahara Maps". Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- http://www.equipement.gov.ma/maritime/PORTS/La%20connaissance-du-milieu/Documents/Annuaire%20des%20cotes_DAKHLA.pdf Archived 2016-06-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- National Agency for Aquaculture Development of Kingdom of Morocco. Call for Expression of Interest Marine Aquaculture Development Project Ined Dakhla Oued Ed Dahab REgion (pdf). Retrieved March 28, 2017

- Around Guides. Angra de Cintra. Retrieved December 27. 2014

- "Fishery Audit Report Checklist" (PDF). Associazione Friend of the Sea. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-20. Retrieved 2014-12-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Malaquias E. A. M.. Ohnheiser T. L.. Oskars R.T.. Willassen E.. 2016. Diversity and systematics of philinid snails (Gastropoda: Cephalaspidea) in West Africa with remarks on the biogeography of the region. DOI: 10.1111/zoj.12478. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved March 20, 2017

- EU funding to fish sector in occupied Western Sahara increases. Retrieved March 30, 2017

- The Sahara Question. 2013. Spanish Consortium Wins Morocco Tender to Develop Aquaculture in Dakhla Region. Retrieved December 26. 2014

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2016-04-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Reeves R. R.. Leatherwood S..1994-1998 Action Plan for the Conservation of Cetaceans: Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales (pdf). The lUCN Conservation Library. Retrieved March 28, 2017

- Economic, Social and Environmental Council of Morocco. 2013. New Development Model for the Southern Provinces (pdf). Retrieved March 28, 2017

- Duke University (2008). "–Spatial Ecology of the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena Glacialis)" (pdf). The ProQuest. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- Reeves R.R. (2001). "Overview of catch history, historic abundance and distribution of right whales in the western North Atlantic and in Cintra Bay, West Africa". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 2: 187–192.

- Silvia A M., Steiner L.,Cascao I., Cruz J.M., Prieto R., Cole T., Hamilton K.P., Baumgartner M. (2012). "Winter sighting of a known western North Atlantic right whale in the Azores" (PDF). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 12: 65–69. Retrieved 2013-04-28.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Reeves, R.R.; Mitchell, E. (1986). "American pelagic whaling for right whales in the North Atlantic" (PDF). Report of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 10): 221–254. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- Notarbartolo di Sciara G., Politi E., Bayed A., Beaubrun.P.C. and Knowlton A. (1998). Donovan P.G.; et al. (eds.). "A Winter Cetacean Survey off Southern Morocco, With a Special Emphasis on Right Whales" (PDF). The Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission À (SC/49/O 3). 48: 547–551. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-04-28.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ed Temperley. "Postcards From The Sahara". MSW-Magic Sea Weed. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- "A whale named Pico". Whale and Dolphin Conservation. 11 April 2014. p. nicola.hodgins's blog. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- Paul Wildlifewriter. 2014. Ghost Town - Geography lessons from Ospreys #437. Retrieved December 26. 2014

- http://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/ScC14_Doc_07_Harbour_porpoise_E_0.pdf

- WalshD. (2006), SeiWhale, Greenpeace, p. the DaveWalshPhoto.com, archived from the original on 2012-12-08, retrieved 2014-12-19

- White R. (2013), At Sea, from Senegal to Western Sahara - Apr 17, 2013 - National Geographic Explorer, the Lindblad Expeditions - National Geographic, retrieved 2014-12-19

- Waerebeek V.K., Andrei M., Sequeirai M., Martin V., Robinea D., Collet A., Ndiaye E.P.V. "Spatial and temporal distribution of the minke Whale,Balaenoptera acutorostrata (Lacépede, 1804), in the southernnortheast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, With reference to stock identity" (PDF). J. Cetacean Res. Manag. l (3): 223–237. Retrieved 2014-12-20.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Tiwari M., Aksissou M., Semmoumy S., Ouakka K. (2006). Morocco Footprint Handbook. Footprint Travel Guides. p. 265. ISBN 9781907263316. Retrieved 2014-12-27.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Footprint Travel Guides". p. South into the Sahara. Archived from the original on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- Johnson M.W.; Karamanlidis A.A.; Dendrinos P.; Larrinoa D.F.P.; Gazo M.; González M.L.; Güçlüsoy H.; Pires R.; Schnellmann M., Mediterranean Monk Seal Fact Sheet, The Monachus Guardian, retrieved 2014-12-19

- Tiwari M., Aksissou M., Semmoumy S., Ouakka K. (2006). "Sea Turtle Surveys in Southern Morocco (Plage Blanche – Porto Rico) in July 2006" (PDF). A Report to the Institut National de Recherche Halieutique, Casablanca, Kingdom of Morocco. Retrieved 2014-12-19.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Deserts and xeric shrublands - Atlantic coastal desert". p. WWF-World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- Rufino R.; Neves R.; Pina J.P. (1998). "Wintering waders in Dakhla Bay, Western Sahara" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin. 87: 26–29. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- Dailey J. 2014. UV and the Gulf of Cintra. Retrieved December 26. 2014

- Triptrafic1. 2012. Sur les traces de l’Aéropostale.. http://www.Trafic-Amenage.com. Retrieved January 1, 2015

- Viaje Transahariano Enero 2012

- Western Sahara (Morocco): Tan-Tan – Fort Guerguerat (pdf). Retrieved March 28, 2017