Edward Bouverie Pusey

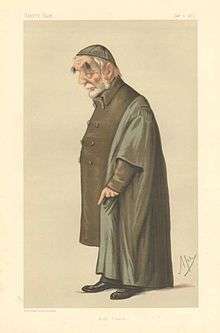

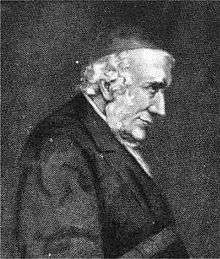

Edward Bouverie Pusey (/ˈpjuːzi/; 22 August 1800 – 16 September 1882) was an English churchman, for more than fifty years Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Oxford. He was one of the leading figures in the Oxford Movement.

Early years

He was born at Pusey House in the village of Pusey in Berkshire (today a part of Oxfordshire). His father, Philip Bouverie-Pusey, who was born Philip Bouverie and died in 1828, was a younger son of Jacob des Bouverie, 1st Viscount Folkestone; he adopted the name of Pusey on succeeding to the manorial estates there. His mother, Lady Lucy Pusey, the only daughter of Robert Sherard, 4th Earl of Harborough, was the widow of Sir Thomas Cave, 7th Baronet, MP before her marriage to his father in 1798. Among his siblings was older brother Philip Pusey and sister Charlotte married Richard Lynch Cotton.[1][2]

Pusey attended the preparatory school of the Rev. Richard Roberts in Mitcham. He then attended Eton College, where he was taught by Thomas Carter, father of Thomas Thellusson Carter. For university admission he was tutored for a period by Edward Maltby.[3][4]

In 1819 Pusey became a commoner of Christ Church, a college at the University of Oxford, where Thomas Vowler Short was his tutor. He graduated in 1822 with a first.[3]

Fellow and professor

During 1823 Pusey was elected by competition to a fellowship at Oriel College, Oxford.[3] John Henry Newman and John Keble were already there as fellows.[1]

Between 1825 and 1827, Pusey studied Oriental languages and German theology at the University of Göttingen.[1] A claim that, during the 1820s, only two Oxford academics knew German, one being Edward Cardwell, was advanced by Henry Liddon; but was not well evidenced, given that Alexander Nicoll, ignored by Liddon, corresponded in German.[5][6]

In 1828 Pusey took holy orders, and he married soon afterwards. His opinions had been influenced by German trends in theology.[7] That year, also, the Duke of Wellington as Prime Minister appointed Pusey as Regius Professor of Hebrew at Oxford, with the associated canonry of Christ Church.[1]

Oxford Movement

%3B_Edward_Bouverie_Pusey%3B_Anthony_Ashley-Cooper%2C_7th_Earl_of_Shaftesbury)_by_Matt_Somerville_Morgan.jpg)

By the end of 1833, Pusey began sympathising with the authors of the Tracts for the Times.[1] He published Tract XVIII, on fasting, at the end of 1833, adding his initials (until then the tracts had been unsigned).[8] "He was not, however, fully associated with the movement till 1835 and 1836, when he published his tract on baptism and started the Library of the Fathers".[9]

When John Henry Newman quit the Church of England for the Roman Catholic church around 1841, Pusey became the main promoter of Oxfordianism, with better access to religious officials than John Keble with his rural parsonage. But Pusey himself was a widower, having lost his wife during 1839, and much affected by personal grief.[10] Oxfordianism was known popularly as Puseyism and its adherents as Puseyites. Some occasions when Pusey preached at his university marked distinct stages for the High Church philosophy he promoted. The practice of confession in the Church of England practically dates from his two sermons on The Entire Absolution of the Penitent, during 1846, which both revived high sacramental doctrine and advocated revival of the penitential system which medieval theologians had appended to it. The 1853 sermon on The Presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist, first formulated the doctrine which became largely the basis for the theology of his devotees, and transformed the practices of Anglican worship.[1]

Controversialist

Pusey studied the Church Fathers, and the Caroline Divines who revived traditions of pre-Reformation teaching. His sermon at the university during May 1843, The Holy Eucharist, a Comfort to the Penitent caused him to be suspended for two years from preaching. The condemned sermon soon sold 18,000 copies.[1]

Pusey was involved with theological and academic controversies, occupied with articles, letters, treatises and sermons. He was involved with the Gorham controversy of 1850, with the question of Oxford reform during 1854, with the prosecution of some of the writers of Essays and Reviews, especially of Benjamin Jowett, during 1863, and with the question as to the reform of the marriage laws from 1849 to the end of his life.[1]

By reviving the doctrine of the Real Presence, Pusey contributed to the increase of ritualism in the Church of England. He had little sympathy with ritualists, however, and protested that as part of a university sermon of 1859. He came to defend those who were accused of violating the law by their practice of ritual; but the Ritualists largely ignored the Puseyites.[1]

Later life and legacy

Pusey edited the Library of the Fathers, a series of translations of the work of the Church fathers. Among the translators was his contemporary at Christ Church, Charles Dodgson. He also befriended and assisted Dodgson's son "Lewis Carroll" when he came to Christ Church. When Dodgson Sr. mourned the death of his wife (Carroll's mother), Pusey wrote to him:

I have often thought, since I had to think of this, how, in all adversity, what God takes away He may give us back with increase. One cannot think that any holy earthly love will cease, when we shall "be like the Angels of God in Heaven." Love here must shadow our love there, deeper because spiritual, without any alloy from our sinful nature, and in the fulness of the love of God. But as we grow here by God's grace will be our capacity for endless love.[11]

Not a great orator, Pusey compelled attention by his earnestness. His major influence was as a preacher and spiritual adviser, for which his correspondence was enormous.[1] In private life his habits were simple almost to austerity. He had few personal friends, and rarely mingled with general society; though harsh to opponents, he was gentle to those who knew him, and gave freely to charities. His main characteristic was a capacity for detailed work.[1]

From 1880 Pusey was seen by only a few persons. His strength gradually decreased, and he died on 16 September 1882, after a brief illness. He was buried at Oxford in the cathedral of which he had been for fifty-four years a canon. In his memory his friends purchased his library, and bought for it a house in Oxford, now Pusey House. It was endowed with funds for librarians, who were to perpetuate in the university Pusey's principles.[1]

Works

Pusey's first work, An Historical Enquiry into the Probable Causes of the Rationalist Character Lately Predominant in the Theology of Germany of 1828, was an answer to Hugh James Rose's Cambridge lectures on rationalist tendencies in German theology. Rose's State of Protestantism in Germany Described has been called "over-simplified and polemical", and Pusey had been encouraged by German friends to reply.[1][12][3] Pusey showed sympathy with the Pietists; misunderstood, he was himself accused of having rationalist opinions. During 1830 he published a second part of the Historical Enquiry.[1]

Other major works by Pusey were:

- two books on the Eucharist, The Doctrine of the Real Presence (1855) and The Real Presence ... the Doctrine of the English Church (1857);

- Daniel the Prophet, supporting the traditional historical dating of that book;

- The Minor Prophets, with Commentary, his main contribution as Professor of Hebrew;

- the Eirenicon, an endeavour to find a basis of union between the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church);[1]

- What is of Faith as to Everlasting Punishment: In Reply to Dr. Farrar's Challenge in His "Eternal Hope", 1879 (1881), in the controversy over everlasting punishment on Eternal Hope (1878) by Frederic William Farrar[13][14]

Christus consolator (1883) was published after his death, edited by his godson and friend George Edward Jelf.[15]

Veneration

The Church of England remembers Pusey annually with a feast day on the anniversary of his death; the Episcopal Church translates his memorial on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) to 18 September.

Family

Pusey married during 1828 Maria Catherine Barker (1801–1839), daughter of Raymond Barker of Fairford Park; they had a son and three daughters. His son, Philip Edward (1830–1880), edited an edition of Saint Cyril of Alexandria's commentary on the minor prophets.[1][3]

See also

- Sacramental union

- Friedrich Tholuck

- Frederick Field (contributor to the Bibliotheca Patrum)

References

-

- Nockles, Peter B. "Cotton, Richard Lynch". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6423. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cobb, Peter G. "Pusey, Edward Bouverie". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22910. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bonham, Valerie. "Carter, Thomas Thellusson". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32314. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Denys P. Leighton (30 November 2015). The Greenian Moment: T. H. Green, Religion and Political Argument in Victorian Britain. Andrews UK Limited. p. 64 note 72. ISBN 978-1-84540-875-6.

- M. G. Brock; M. C. Curthoys (1 November 1997). Nineteenth-century Oxford. Clarendon Press. pp. 38 note 205. ISBN 978-0-19-951016-0.

- Gregory P. Elder (1996). Chronic Vigour: Darwin, Anglicans, Catholics, and the Development of a Doctrine of Providential Evolution. University Press of America. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7618-0242-6.

- Brian Douglas (24 July 2015). The Eucharistic Theology of Edward Bouverie Pusey: Sources, Context and Doctrine within the Oxford Movement and Beyond. BRILL. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-30459-8.

- Newman's Apologia, p. 136.

- Chadwick, Owen (1987). The Victorian Church Part One 1829–1859. London: SCM Press. pp. 197–8. ISBN 0334024099.

- The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll

- Don Cupitt (29 July 1988). Sea of Faith. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-521-34420-3.

- Edward Bouverie Pusey (1881). What is of Faith as to Everlasting Punishment: In Reply to Dr. Farrar's Challenge in His ʻEternal Hope,' 1879. James Parker & Company.

- Vance, Norman. "Farrar, Frederic William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33088. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Davie, Peter. "Jelf, George Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34169. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Strong, Rowan, and Carol Engelhardt Herringer, eds. Edward Bouverie Pusey and the Oxford Movement (Anthem Press; 2013) 164 pages; new essays by scholars

- Faught, C. Brad (2003). The Oxford Movement: A Thematic History of the Tractarians and Their Times, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02249-9.

- James Harrison Rigg, Character and Life-Work of Dr Pusey (1883)

- Bourchier Wrey Savile, Dr Pusey, an Historic Sketch, with Some Account of the Oxford Movement (1883)

- Life of Edward Bouverie Pusey by Henry Parry Liddon, completed by J. C. Johnston and R. J. Wilson (5 vols, 1893–1899),

- Newman's Apologia, and other literature of the Oxford Movement.

- Mark Chapman, "A Catholicism of the Word and a Catholicism of Devotion: Pusey, Newman and the first Eirenicon," Zeitschrift für Neuere Theologiegeschichte, 14,2, 2007, 167–190.

- Geck, Albrecht, From Modern-Orthodox Protestantism to Anglo-Catholicism: An Enquiry into the Probable Causes of the Revolution of Pusey's Theology, in: Rowan Strong/Carol Engelhardt Herringer (edd.), Edward Bouverie Pusey and the Oxford Movement, London/New York/New Delhi (Anthem Press) 2012, 49–66.

- Geck, Albrecht, "Pusey, Tholuck and the Oxford Movement," in: Stewart J. Brown/Peter B. Nockles (ed.), The Oxford Movement. Europe and the Wider World 1830–1930, Cambridge (Cambridge University Press) 2012, 168–184.

- Geck, Albrecht (Hg.), Authorität und Glaube. Edward Bouverie Pusey und Friedrich August Gottreu Tholuck im Briefwechsel (1825–1865). Teil 1–3: in: Zeitschrift für Neuere Theologiegeschichte 10 (2003), 253–317; 12 (2005), 89–155; 13 (2006), 41–124.

- Geck, Albrecht, "Edward Bouverie Pusey. Hochkirchliche Erweckung," in: Neuner, Peter/Wenz, Gunter (eds.), Theologen des 19. Jahrhunderts. Eine Einführung, Darmstadt 2002, 108–126.

- Geck, Albrecht, "Friendship in Faith. E.B. Pusey (1800–1882) und F.A.G. Tholuck (1799–1877) im Kampf gegen Rationalismus und Pantheismus – Schlaglichter auf eine englisch-deutsche Korrespondenz," Pietismus und Neuzeit, 27 (2001), 91–117.

- Geck, Albrecht, "The Concept of History in E.B. Pusey’s First Enquiry into German Theology and its German Background," Journal of Theological Studies, NS 38/2, 1987, 387–408.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Bouverie Pusey |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Bouverie Pusey. |

- Pusey's Works from Project Canterbury

- Pusey, Edward Bouverie in Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge

- Pusey Family papers, 1836-1882 at Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology

- Pusey House

- What is of faith, as to everlasting punishment, in reply to Dr Farrar's challenge in his 'Eternal Hope' (1879) published 1880

- Works by Edward Bouverie Pusey at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Edward Bouverie Pusey at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Edward Bouverie Pusey at Internet Archive

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.