Church of Saint-Sulpice, Jumet

The Church of Saint Sulpice (French: Église Saint-Sulpice; French pronunciation: [sɛ̃sylpis]) is a Roman Catholic church in Jumet, a neighborhood of the Belgian city of Charleroi in Hainaut, Wallonia.[1] It is dedicated to Sulpitius the Pious. The oldest material traces of a religious building on the site date back to the 10th century. Three churches preceding the current construction were identified during excavations carried out in 1967. The current building was built between 1750 and 1753 in a classical style, by an anonymous architect.[2] The brick and limestone church is quite homogeneous. It's composed of six bayed naves flanked by aisles, a three-sided transept and a choir with a polygonal ambulatory with a sacristy in its axis. The chamfered base is in dimension stone on the frontage, in rubble stones and sandstone for the rest. All the angles of the building are toothed and every second stone is bossed. The church has been listed as a Belgian cultural heritage site since 1949.

| Church of Saint-Sulpice | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| District | Diocese of Tournai |

| Province | |

| Region | |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Church |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Charleroi, Hainaut, Belgium |

| Municipality | |

| Geographic coordinates | 50.450875°N 4.425897°E |

| Architecture | |

| Groundbreaking | 1750 |

| Completed | 1753 |

Historical context

Both the church and Jumet itself were listed in 868 in the polyptych of Lobbes Abbey.[3][4] Despite its age, it is rarely mentioned in records. Most of the relevant documents were probably lost in the destruction of the State Archives in Mons and of the episcopal archives of Tournai at the beginning of the Second World War.[5]

Before the French Revolution, Jumet was part of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège; the abbot of Lobbes was sovereign lord by appointment of the Prince-bishop.[6] However, its neighbouring states, Hainaut and Brabant, challenged Liège's claim to Jumet. Over time, Brabant gained in influence, which seemed in accordance with the local population's wish.[7] By the 1730s, Brabant was acting as if it completely owned Jumet. During the 1740s, Duchess Maria Theresa of Austria and the Council of Brabant instituted administrative reforms at the request of the mayor and the magistrate. On 28 June 1780, Prince-Bishop François-Charles de Velbrück officially yielded the lordship of Jumet to Brabant.[8] During the period of French rule, Jumet belonged to the department of Jemappes, which became part of the province of Hainaut after the fall of Napoleon.

The church's predecessors, whose patron saint remains unknown, belonged to a parish of the old deanery of Fleurus, part of the diocese of Liège. In 1559, during reforms of the episcopal hierarchy of the Low Countries, this parish was first assigned to the newly created diocese of Namur,[9] and later to the diocese of Tournai in the Concordat of 1801.

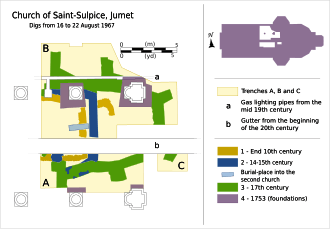

The excavation of 1967

In 1967, the church underwent a major restoration led by Simon Brigode, architect and professor at the University of Leuven. During this restoration, excavations were conducted by Luc-Francis Genicot, assistant professor at the University of Leuven, from 16–22 August 1967.

These excavations were conducted in a limited area which turned out to be of significance.[10] although the restoration work had already destroyed some of the ancient foundations.[11]

The construction of the current church had already profoundly modified the earlier site. The 18th-century flooring is lower than earlier levels; only the lowest levels of the old foundation still remained. During the excavations they found no foundation, no under-pavement, no lime mortar runoff, and no altar base.[11] The sepulchre lay 19 centimetres (7.5 in) under the current flooring level only.[12]

The work done in the 19th and 20th centuries removed ancient traces. A thin brick gutter to hold gas lighting pipes was installed during the second half of the 19th century, cutting across the B trench.[13] An early 20th-century gutter, constructed roughly along the lengthwise axis of the current church, cut through the old foundations.[14]

These surveys made it possible to correctly locate the building's successive stages of growth.[12]

The successive churches

Three religious buildings that preceded the current church were uncovered during the excavations.

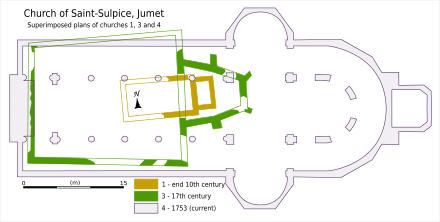

First church

Pre-Romanesque, the first building was formed of a rectangular chamber composed of a plain nave 4.7 metres (5.1 yd) wide, whose length the excavations did not manage to determine. It is possible that as in other small churches of the early Middle Ages, the length of the church was double its width. This edifice may have been the church consecrated between 959 and 971 by Eraclus, abbot of Lobbes and bishop of Liège, which was mentioned in the "Eraclus charter".[15]

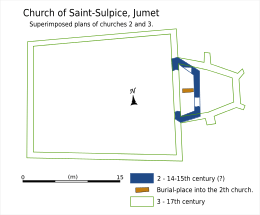

Second church

During the excavation, the sole trace of the second church — the foundation of an irregular three-sided apse— was found. How the building was constructed toward the narthex remains unclear. However, it is known that this side ended with a tower because Jehan Camal, the local priest, bequeathed 50 livres towards the repairing of the tower and the installation of a bell in his will of 1517.[16] This tower is probably the same one mentioned in the 17th century, which was demolished for the construction of the 18th century church.[17] The size of the choir/chancel suggests a three-apsed construction, maybe similar to the third church.[18] As well as the main altar, a Pouillé ecclesiastical register from 1445 mentioned an altar devoted to Saint Nicholas, and another from 1518 mentions an altar devoted to the Virgin Mary.[19]

Noting the similarities to the choir in Saint-Martin's church at Marcinelle, rebuilt at the end of the 15th century, Luc-Francis Genicot hypothesised that it took inspiration from Jumet's earlier design, possibly from the 14th century.[20]

In the choir lies a burial place containing a skeleton in a nailed oak coffin. The presence of embroidered cloth and the location suggests that it is the tomb of a priest, probably the local parson.[21]

Third church

The chancel of the third edifice probably dates back to the middle of the 17th century.[22] This church is eight times bigger than the first. The chancel is of a pentagonal design 8.25 metres (9.02 yd) deep. It is consolidated by four buttresses, suggesting that it was once covered by a solid vault, probably of gothic design. The nave, 22 metres (24 yd) long and of an estimated width of 20 metres (22 yd), is slightly trapezium-shaped[23] and has two aisles. The scale of the aisles lets us imagine a building of the hall church type, like many that existed in Hainault in the 15th and 16th century.

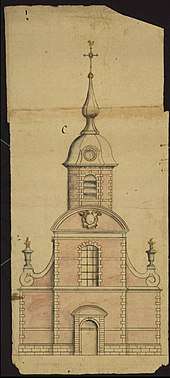

The tower stands against the church frontage. It underwent an important restoration in 1670 and a clock was installed in 1681. This bell-tower was probably square and roughly 6.4 metres (7.0 yd) long on each side. It was capped by an octagonal pointed spire, topped by a big finial cross and a weathercock reaching to 38 metres (42 yd) high.[2]

In 1710, the state of the church again called for serious repairs, and Jumet's bailiff, Jean de Vigneron, asked the abbot of Lobbes, a big tithe collector, to build a new church. The abbey could not meet the expense.[24] Finally, after a lawsuit, an agreement was reached for the repairs to the church including the choir, the tower and the roof of the nave.[25]

Present church

The present church was built between 1750 and 1753 by an anonymous architect. The original plans consist of five coloured sheets.[26] They have been numbered from A to E without any obvious order, probably after the completion of the construction. The C sheet did not belong to the first file, but the five drawings are from the same author. The E sheet has notes on the back where the name of D. De Lados appears twice, suggesting that it could be the name of the architect.[27]

Before 1750, the old church was demolished and the ground leveled.[11] This leveling is probably why the present church isn't correctly oriented, unlike the original church, whose choir faced due east.[28]

At the time, the design was considered ambitious and excessive for the locality. Tensions took place between the architect and the sponsors, including the abbot of Lobbes, Théodulphe Barnabé (abbot from 1728 to 1752).[25] Construction lagged and, even though old materials were re-used in the base and the pavements,[22] the cost was five times the original estimate :

We have been greatly wronged for the erection of this church[...]because the church building, instead of costing us twenty thousand florins, is now costing us at least a hundred thousand [...] The architect has deceived us by increasing the length of the so-mentioned church by twenty-nine feet, and many other things

— Complaint quoted by L-F. Genicot, [25]

The initial plan intended to re-integrate the old tower. An amendment definitely scrapped all the past.[22] This project of a new tower probably belonged to that part of the many other things that were mentioned in the complaint.

This conflict ended with a trial before the Sovereign Council of Brabant. The architect was forced to reduce the scale of the project. This is evident by examining the successive frontage projects[28] and comparing the size of the achieved high parts and the planned size on the original elevation drawing. The construction continued but with some delay. The church was finished in 1753.[22]

The steeple was designed to receive three bells. Two bells are attested, and there is no formal proof of the existence of the third.[29]

On the east side, a bell from 1590 is adorned with the image of the Virgin and has the inscription: Micael Willelmus coadiutor Lobiensis me fecit[30] – 1590 – Maître Jean Grongnart, founder[29][31]

On the west side, the second bell was probably in bad shape because it was remelted in 1772, as the inscription attests : + In the year 1772 I was remelted at the expense of the community of Jumet by Simon Chevresson and Deforest.[29]

It's probable that the French revolution induced structural damage because a budget was allocated by the local administration for the repair of window panes and the roof in 1797.[32] In 1808, three new altars were built.[33]

In 1835, the church underwent an important restoration. Part of the pavement was replaced, a new set of furniture was put in, the altars transformed[32] and the master altar re-dedicated.[33]

In the brickwork of the master altar, removed during the 1968 restorations, a wooden reliquary casket with a glass lid was discovered. It contained two bones held together by a copper thread. Between them was a paper document in a very bad shape, nearly unreadable, dated 1835. Possibly that the reliquary is older than that and was put there when the altar was re-devoted.[34][35]

In 1840, a pipe organ was installed, the work of organ builder Hypolite Loret of Brussels. The instrument was upgraded in 1873.[32]

In 1943, German occupation authorities commandeered the bells. The 1590 bell was taken down and shipped to Germany.[36] After the war, it was found and re-installed in the steeple.[28][37]

Architecture and furniture

The church is made of brick and limestone and was built in the classic style. Overall, it is uniform in appearance. It's composed of six bayed naves flanked on either side by aisles, a three-sided transept and a choir with a polygonal ambulatory with a sacristy in its axis. The chamfered base is in dimension stone on the frontage, in rubble stones and sandstone for the rest. All the angles of the building are toothed and every second stone is bossed.[1]

The windows, except those of the tower, all have a gouged limestone frame cut with protruding teeth, with a curved arch and window aprons joined together by a limestone band going around the whole building. Similarly conceived half-windows are found on the second level in the background, under the cornice.[1]

The frontage has two levels, with above them a curved pediment. On the first level, two belts proceed further than the central part to the side frontages under the voluted ailerons placed on both sides of the second level. Above the pediment, a square tower is made up of two stories separated by a belt. The tower has a polygonal steeple on a pyramidal base. The limestone portal is preceded by several steps. It's flanked by pilasters with crosswalls that hold an entablature and a curved pediment. There is an arched door.[1]

A secondary door, preceded by ten steps, is pierced by the first north aisle bay.

The interior is quite bright, painted in white and grey. It is covered by barrel vaults. The columns of the nave are of tuscan style. The piers of the choir and of the transept are crowned with a voluted capitals.[1]

The church contains noted panelling and furniture.[38]

In the church is a baptismal font from the 11th or 12th century. It consists of a stone bowl slightly flared but circular, flanked by four engaged columns on a base. The columns end with a roughly cut human head, of which two out of four are missing. The style is Romanesque and the font archaic: straight nose and barely cleared, skin-deep eyes, mouth expressionless. These details are characteristic of Romanesque workshops from the 11th and 12th centuries. However, the disposal of Jumet differs from other fonts known by the feature that the heads are borne directly by columns. Usually, the head is supported in cantilever by a kind of console, as is the case, for example, in Gerpinnes.[39]

The furniture also contains an altar devoted to Our-Lady of Tongre and a communion bench, both dating from the 17th century.[38]

General view of the nave from the choir loft.

General view of the nave from the choir loft. The north aisle and tuscan columns, towards the choir.

The north aisle and tuscan columns, towards the choir. The nave and organs as seen from the choir.

The nave and organs as seen from the choir. The choir with ambulatory, the tabernacle and the altar.

The choir with ambulatory, the tabernacle and the altar. The baptismal font.[32]

The baptismal font.[32] Altar devoted to our-Lady of Tongre.

Altar devoted to our-Lady of Tongre. Communion bench.

Communion bench.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church of Saint-Sulpice, Jumet. |

References

- PMDB 1994, p. 126.

- Genicot 1969, p. 33

- Genicot 1969, p. 10

- Arcq 1973, p. 100

- Genicot 1969, p. 12

- Arcq 1973, p. 52

- Arcq 1973, p. 53

- Arcq 1973, p. 61

- Genicot 1969, pp. 11–12

- Genicot 1969, p. 9

- Genicot 1969, p. 18

- Genicot 1969, p. 19

- Genicot 1969, p. 22

- Genicot 1969, p. 20

- Genicot 1969, p. 25

- Arcq 1973, p. 102

- Genicot 1969, p. 30

- Genicot 1969, p. 27

- Arcq 1973, p. 101

- Genicot 1969, p. 28

- Genicot 1969, pp. 38–39

- Genicot 1969, p. 36

- Considering that the restitution is correct, because the south-west angle hasn't been maintained (Genicot 1969, p. 30).

- Arcq 1973, p. 103

- Genicot 1969, p. 15

- Kept at State Archives in Belgium (Genicot 1969, p. 16)

- Genicot 1969, pp. 16–17

- Arcq 1973, p. 104

- Arcq 1973, p. 104 ; 106

- Michel Willame was co-helper from 1580 to 1598 of the abbey of Lobbes, Ermin François, he was elected himself in 1598 and died in 1600 (Genicot 1969, p. 16).

- Jean Grongnart belongs to a dynasty of founders that worked in Hainaut during the 16th and 17th century (Genicot 1969, p. 16).

- Arcq 1973, p. 105

- Genicot 1969, p. 41

- Genicot 1969, pp. 40–41

- Photography of the reliquary on the website of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage

- Maerten & Colignon 2012, pp. 38–39

- Photograph of the bell on the website of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage

- "Saint-Suplice church in Jumet". Le pays de Charleroi. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- Brigode 1936, p. 6-8.

External links

- Old photographs of the Saint-Sulpice church on the website of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA)

Bibliography

- Le patrimoine monumental de la Belgique, Wallonie, Hainaut, Arrondissement de Charleroi (in French). 20. Pierre Mardaga, éditeur. 1994. ISBN 2-87009-588-0. OCLC 312155565.

- Arcq, Robert (1973). Jumet, Pages d'histoire (in French). Jumet. OCLC 704497631.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brigode, Simon (1936). "Notes sur quelques sculptures anciennes conservées à Jumet". Bulletin de la Société royale d'archéologie et de paléontologie de Charleroi (in French): 6–10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brutsaert, Emmanuel; Menne, Gilbert; De Meester, Johan (2009). Province du Hainaut, Histoire et patrimoine des communes de Belgique (in French). Bruxelles: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-599-3. OCLC 690552502.

- Genicot, Luc-Francis (1969). "Fouilles en l'église Saint-Sulpice de Jumet". Documents et rapports de la Société royale d'archéologie et de paléontologie de Charleroi (in French). LIV: 10–39.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maerten, Fabrice; Colignon, Alain (2012). La Wallonie sous l'Occupation, 1940-1945. Villes en guerre (in French). Bruxelles-Waterloo: SOMA-CEGES – Renaissance du Livre. ISBN 978-2-5070-5062-7. OCLC 821263376.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)