Christ's Hospital railway station

Christ's Hospital railway station is near Horsham in West Sussex, England. It is 40 miles 7 chains (64.5 km) down the line from London Bridge via Redhill. It was opened in 1902 by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway and was intended primarily to serve Christ's Hospital, a large independent school which had moved to the area in that year. It now also serves the rural area to the west of Horsham.

| Christ's Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Place | Christ's Hospital |

| Local authority | Horsham, West Sussex |

| Grid reference | TQ14752903 |

| Operations | |

| Station code | CHH |

| Managed by | Southern |

| Number of platforms | 2 (originally 7) |

| DfT category | E |

| Live arrivals/departures, station information and onward connections from National Rail Enquiries | |

| Annual rail passenger usage* | |

| 2014/15 | |

| 2015/16 | |

| 2016/17 | |

| 2017/18 | |

| 2018/19 | |

| History | |

| Original company | London, Brighton and South Coast Railway |

| Post-grouping | Southern Railway Southern Region of British Railways |

| 28 April 1902 | Opened as Christ's Hospital, West Horsham |

| 4 September 1961 | Closed to goods traffic |

| c. 1968 – c. 1972 | Renamed |

| 1972 | Rebuilt |

| National Rail – UK railway stations | |

| * Annual estimated passenger usage based on sales of tickets in stated financial year(s) which end or originate at Christ's Hospital from Office of Rail and Road statistics. Methodology may vary year on year. | |

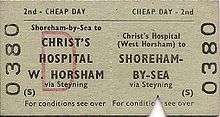

Opened originally as Christ's Hospital (West Horsham),[1] the station was until the mid-1960s an important junction with, in addition to the existing link to Arundel via Pulborough, connections to Guildford via Cranleigh and Brighton via Shoreham-by-Sea.

Services and facilities

The typical Monday-Sunday off peak service is:

- one train per hour to London Victoria

- one train per hour to Bognor Regis

For a period from the late 1960s until c. 1989, many services did not stop at the station.[2]

The station has short platforms.[3]

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horsham | Southern Arun Valley Line |

Billingshurst | ||

| Disused railways | ||||

| Horsham Line and station open |

British Rail Southern Region Cranleigh Line |

Slinfold Line and station closed | ||

| British Rail Southern Region Steyning Line |

Southwater Line and station closed | |||

The ticket office is now open from the first London bound train (Monday to Friday) which is about 06:30, until 10:40 when the office closes.[4] There is also a 'Quick Ticket' machine allowing passengers to purchase tickets when the office is closed.[4] In April 2009, Southern installed display screens to tell passengers when trains are due.

In August 2012, the station won Southern's award for best small/medium station, being described as a "charming friendly station with a homely atmosphere, well presented flower beds and even a charity bookstall."[5] The flower beds are maintained by the Aldingbourne Community Trust.[6]

History

Establishment and early hopes

The site of Christ's Hospital station had been previously used by the Aylesbury Dairy Company which had a small wooden platform on the Mid-Sussex Railway for milk to be taken to London.[7] This platform had fallen into disuse upon the bankruptcy of the dairy after it lavished large sums of money on farm buildings.[7] The estate was purchased in 1897 at a knock-down price by Christ's Hospital school, which had been seeking to move from London.[7] It was expected that the school would attract large numbers of visitors which would need to be accommodated by the railway.[7][8][9] When the school's foundation stone was laid by the Prince of Wales on 23 October 1897, the whole school came down by train to Horsham where a siding was laid for the occasion.[7]

At the time of the school's decision to relocate, the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) had been considering whether to stimulate residential development in the area by opening a station at Stammerham which would be called West Horsham.[7] With the arrival of the school, the LB&SCR believed that even more traffic would be generated and decided to construct a lavish station building at a cost of £30,000 (equivalent to £3,280,923 in 2019[lower-alpha 1]).[10][7][11][12][13] The school partly financed the construction of the station which consequently was built to a similar style as the school's own buildings,[14] using red brick from the nearby Southwater brickworks.[9]

Station buildings and facilities

Five through tracks serving seven platform faces were built just beyond the junction near Stammerham Farm, 2.25 miles (3.62 kilometres) south of Horsham and 40 miles 7 chains (64.5 kilometres) from London Bridge, where the Cranleigh Line diverged northwards from the Mid-Sussex Railway.[12][15][16][17][18][10][19] Two tracks led to three platform faces which curved away to the west for services on the Cranleigh Line and the Steyning Line; the Down line had platforms on both sides (Platform 5) while the Up track used the outside face of an island platform (Platform 4) which was enclosed by the Up and Down Guildford lines.[14][20][8] The two platforms of the island platform were built at a very sharply curving angle to the rest from which they were separated;[8] they were said to represent a southern equivalent of Ambergate railway station.[21] Two tracks served the Mid-Sussex Line: the Up line used the inner face of the island platform (Platform 3) and the Down was the outer face of a second island platform (Platform 2).[20][19] A bidirectional loop line ran on the inner face of the island platform serving a platform adjacent to the main station building.[20][19][8] This third platform (Platform 1) was used mainly at the beginning and end of school terms for the reception and dispatch of pupils' trunks, as well as for holiday specials.[22][23][24] The station was ready to become an important junction serving most of West Sussex with trains travelling from London via Horsham having the option of routes to Pulborough, Shoreham-by-Sea, Guildford and beyond.[25]

The incongruously large station reflected the large numbers of pupils expected daily, as well as the LB&SCR's hopes of large housing developments.[26][16][8] The main platforms were 800 feet (240 metres) long, whilst those on the Guildford line were 500 feet (150 metres) long, each provided with waiting rooms, large frosted glass canopies and decorative brickwork.[27] The main station building was built in an Italianate style with red and white chequered polychrome brickwork filling heavy cross braced bargeboarded gables and repeated over round-head windows beneath.[28][29] A stone water tower on a brick base formed part of the frontage of the station.[30][31] The main station building was described by Pevsner as "West Sussex's only memorable railway station", "one of the best examples in southern England of an unaltered Late Victorian railway building" and "a better building than the Hospital itself" which combined "a perfect anthology of railway forms".[32] The main building faced a large area intended for cabs which was reached by an approach road.[19]

The goods shed was constructed in a different style to the station building, its character owing more to local traditional construction.[33] It housed a crane and a side loading bay with tall doors and a canopy for road vehicles; a smaller office building was tacked on to the side.[33] The adjacent goods yard was served by five sidings.[34] In addition, eight railway cottages were constructed nearby for staff.[34] Access to the goods yard and exit from the Down loop serving platform 1 was controlled by "South Box" (or "B Box") which was brought into use on 27 April 1902 and situated to the west of the station, although it was only infrequently used.[35][36][19] On the opposite side of the station at the end of the Up main line platform was "North Box" (or "A Box"), which replaced a previous box known as Stammerham Junction dating from 1865, possibly at the same time as South Box was brought into use or even a few days earlier.[35][37][19]

Opening

The station opened on 28 April 1902,[38][39][40][41] although the official ceremony took place on Thursday 1 May 1902.[36] The station was initially known as Christ's Hospital (West Horsham), but when tickets were issued to travel to Christ's Hospital school for its opening ceremony on 29 May 1902, they were made out to Stammerham Junction.[36] Special trains bound for the school departed from London Victoria at 1520, London Bridge at 1525 and Sutton at 1540, all due to arrive at Christ's Hospital at 1645.[36] Some of the schoolmasters were dispatched to Victoria and London Bridge to meet the pupils.[36]

A report published in the West Sussex Gazette on 1 May 1902 called into question the wisdom of constructing such a large station for an area which was relatively sparsely populated.[14] The initial service consisted of ten trains to Victoria, seven to Guildford and four to Brighton with Billingshurst served by three stopping services.[36]

Unrealised ambitions and gradual decline

In the event, the LB&SCR's expectation of an income from the station to match the size of its premises would be defeated by two developments. Firstly, Christ's Hospital school only ever accommodated boarders; the LB&SCR had possibly not been informed of this when designing the station.[9] Secondly, the anticipated residential development in the area did not materialise. This was largely because the school had purchased much of the land around the junction and had no desire to see their green fields filled with housing, the school having left London precisely to reestablish in greener surroundings.[24][36] The LB&SCR was therefore left with a white elephant: the capacity and stature of the station being vastly out of proportion with its status as a useful rural interchange, rather than an important railway junction serving much of West Sussex.[9]

The station was undoubtedly a useful interchange with trains travelling in four directions, but its own passenger receipts remained low due to the fact that its use by people unconnected with the school was limited.[14] By 1953 the loop line intended for school trains was rusty due to lack of use.[8] Much of the station's usefulness was lost in the 1960s when the Steyning Line and Cranleigh Line were closed, both having been put forward for closure in The Reshaping of British Railways report of 1963.[42] The last train from Guildford ran on 14 July 1965 at 1855 and returned at 2034.[43] The event was marked at Christ's Hospital station by pupils from Christ's Hospital school who sang Abide with Me as the train pulled away.[44][43] The buildings on the Guildford platforms were demolished shortly afterwards.[45]

The 1960s marked the start of a period of rationalisation which began with the closure of the goods yard on 4 September 1961, it having been little used in latter days.[46][34][47][20] South Box closed around the same time.[35] For a time the station was itself threatened with closure[48] but survived following a public outcry and the presentation of a petition with 3,046 signatures to the Queen.[43][49] The station's name was also changed to Christ's Hospital, with timetables published from 1968 showing the change.[40]

Demolition of station buildings

In spite of a plea from the architectural critic Ian Nairn that Christ's Hospital station should be preserved in its original form,[21] rationalisation began in autumn 1972 and continued until December, involving much simplification of the buildings and track layout to reduce them to a size more suited to the station's existing traffic.[50][51][36] The station was rebuilt out of all recognition with demolition of all the main station buildings and reduction of the number of platforms from seven to two.[50][52][51][16][18][43] The platforms that remain in use were originally numbered "3" and "4"; these are now respectively the Down and Up platforms served by the double track line between Horsham and Billingshurst.[53]

Rubble from the works was used to infill the road for platform 1 and a section of the subway beneath it.[45] In the place of the station building was a car park.[45] The Guildford platforms were fenced off from the rest of the station and they remain in evidence in an overgrown state.[54][43][53]

The destruction of the station building has been described as a "mammoth act of vandalism"[55] and a "slaughter".[45] Only the subway and the waiting room on the Down main line platform survived and this was adapted to house toilets and a booking office.[55][56] A bus-stop type shelter was provided on platform 2[45] and has been described as being "of a type that should have been outdated 100 years ago."[53] Prior to demolition a "funeral party" was held by pupils and staff of Christ's Hospital school; 120 people attended with special tickets printed with a black border.[57][58]

The goods shed, which had been used as a lost property store until around 1950, survived and was rented to Scottish & Newcastle as a distribution depot.[45] Until relatively recently, there was a staffed ticket office in a box on the up platform, adjacent to a surviving semaphore signal.[18][35][54][59]

In popular culture

The station, including the original building, appears as "Longhampton" in the 1965 comedy film Rotten to the Core, which featured SECR N class No. 31405.[60]

References

Notes

- Catford, Nick. "Christ's Hospital railway station". Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Mitchell & Smith (1989), fig. 81.

- Southern (January 2012). "Southern Railway Ltd: Railway Safety Authorisation". p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- National Rail. "National Rail Enquiries: Station facilities for Christ's Hospital". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- "Southern 'Stars and Tsars' shine bright at awards". Southern. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- "Aldingbourne Trust". Southern. 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Gray (1975), p. 55.

- Norris (1953), p. 349.

- Elton (1999), p. 178.

- Oppitz (2005), p. 61.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 50.

- Course (1974), p. 184.

- Turner (1979), p. 165.

- Hodd (1975), p. 38.

- White (1987), p. 77.

- White (1992), p. 106.

- Hamilton Ellis (1971), p. 222.

- Body (1989), p. 71.

- Turner (1979), p. 166.

- Course (1974), p. 185.

- Nairn & Pevsner (1985), p. 188.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 54.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 44.

- Oppitz (2005), p. 62.

- Oppitz (2005), pp. 61-62.

- Mitchell & Smith (1987), fig. 44.

- Gray (1975), pp. 55-56.

- Symes & Cole (1972), pp. 102-104.

- Biddle (1973), p. 207.

- Biddle (1973), p. 224.

- Symes & Cole (1972), p. 102.

- Nairn & Pevsner (1985), pp. 40, 188.

- Symes & Cole (1972), p. 107.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 51.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 55.

- Gray (1975), p. 56.

- Mitchell & Smith (1987), fig. 45.

- Hamilton Ellis (1971), p. 20.

- Butt (1995), p. 61.

- Quick (2009), p. 125.

- Baggs, A.P.; Currie, C.R.J.; Elrington, C.R.; Keeling, S.M.; Rowland, A.M. (1986). "Itchingfield". In Hudson, T.P. (ed.). A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 2: Bramber Rape (North-Western Part) including Horsham. Victoria County History. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- Beeching (1963), p. 107.

- Oppitz (2005), p. 64.

- Welbourn (2000), p. 53.

- Gray (1975), p. 75.

- Clinker (1978), p. 29.

- Gray (1975), p. 68.

- Gray (1975), p. 71.

- Gray (1975), p. 69.

- Gough (2000), p. 65.

- Welbourn (2000), p. 54.

- White (1987), p. 184.

- Elton (1999), p. 180.

- Gough (2000), p. 64.

- Mitchell & Smith (1986), fig. 56.

- Mitchell & Smith (1987), fig. 54.

- Mitchell & Smith (1987), fig. 53.

- Gray (1975), appendix 3.

- Mitchell & Smith (1989), fig. 80.

- Mitchell & Smith (1987), fig. 51.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Sources

- Beeching, Richard (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways" (PDF). HMSO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biddle, Gordon (1973). Victorian Stations. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-715359-49-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Body, Geoffrey (1989) [1984]. Railways of the Southern Region. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-297-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Clinker, C.R. (October 1978). Clinker's Register of Closed Passenger Stations and Goods Depots in England, Scotland and Wales 1830–1977. Bristol: Avon-Anglia Publications & Services. ISBN 0-905466-19-5. OCLC 5726624.

- Course, Edwin (1974). The Railways of Southern England: Secondary and Branch Lines. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-713428-35-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elton, M.S. (April 1999). "The Horsham & Guildford Direct Railway 1860 - 1965". BackTrack. 13 (4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gough, Terry (2000) [1993]. British Railways Past and Present: Surrey and West Sussex. Kettering, Northants: Past & Present Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85895-002-0. No. 18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Adrian (1975). The Railways of Mid-Sussex. Tarrant Hinton, Dorset: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-853611-75-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamilton Ellis, C. (1971) [1960]. The London Brighton and South Coast Railway. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-71100-269-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hodd, H.R. (1975). The Horsham-Guildford Direct Railway. Tarrant Hinton, Dorset: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-853611-70-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1987) [1982]. Branch Lines to Horsham. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-02-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (August 1986). Southern Main Lines: Crawley to Littlehampton. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-34-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (November 1989). West Sussex Railways in the 1980s. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-70-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1985) [1965]. Sussex (Buildings of England). Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-071028-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norris, P.J. (September 1953). "From Horsham to Guildford". Trains Illustrated. VI (9).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oppitz, Leslie (2005) [2001]. Lost Railways of Sussex. Newbury, Berks: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-853066-97-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quick, Michael (2009) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.). Oxford: Railway and Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5. OCLC 612226077.

- Symes, Rodney; Cole, David (1972). Railway Architecture of the South-East. Reading, Berkshire: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-850450-70-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, John Howard (1979). The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway: Completion & Maturity. 3. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-1198-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welbourn, Nigel (2000) [1996]. Lost Lines Southern. Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-711024-58-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, H.P. (1987) [1976]. Forgotten Railways: South-East England (Forgotten Railways Series). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-946537-37-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, H.P. (1992) [1961]. A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Southern England. 2. Nairn: David St John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-77-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christ's Hospital railway station. |

- Train times and station information for Christ's Hospital railway station from National Rail