Chernobyl

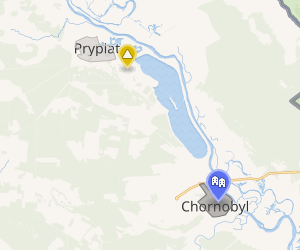

Chernobyl (/tʃɜːrˈnoʊbəl/, UK: /tʃɜːrˈnɒbəl/), also known as Chornobyl (Ukrainian: Чорнобиль, romanized: Chornobyl'), is a partially abandoned city in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, situated in the Ivankiv Raion of northern Kiev Oblast, Ukraine. Chernobyl is about 90 kilometres (60 mi) north of Kiev, and 160 kilometres (100 mi) southwest of the Belarusian city of Gomel. Before its evacuation, the city had about 14,000 residents,[1] while around 1,000 people live in the city today.

Chernobyl Чорнобиль | |

|---|---|

| Chornobyl | |

.jpg) Chernobyl's Old City Hall building | |

Chernobyl ( | |

Chernobyl Kiev Location of Chernobyl in Ukraine | |

| Coordinates: 51°16′20″N 30°13′27″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | Chernobyl Raion (1923–1988) Ivankiv Raion (since 1988) |

| Founded | 1193 |

| City status | 1941 |

| Government | |

| • Administration | State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management |

| Postal code | 07270 |

| Area code(s) | +380-4593 |

First mentioned as a ducal hunting lodge in 1193, the city has changed hands multiple times over the course of history. Jews were introduced to the city in the 16th century, and a now-defunct monastery was established near the city in 1626. By the end of the 18th century, Chernobyl was a major centre of Hasidic Judaism under the Twersky Dynasty, who left Chernobyl after the city was subject to pogroms in the early 20th century. The Jewish community was later destroyed during the Holocaust. Chernobyl was chosen as the site of Ukraine's first nuclear power plant in 1972, located 15 kilometres (9 mi) north of the city, which opened in 1977. Chernobyl was evacuated on 5 May 1986, 9 days after a catastrophic nuclear disaster at the plant, which was the largest nuclear disaster in history. Along with the residents of the nearby city of Pripyat, which was built as a home for the plant's workers, the population was relocated to the newly built city of Slavutych, and most have never returned.

The city was the administrative centre of Chernobyl Raion (district) from 1923. After the disaster, in 1988, the raion was dissolved and administration was transferred to the neighbouring Ivankiv Raion.

Although Chernobyl is primarily a ghost town today, a small number of people still live there, in houses marked with signs that read, "Owner of this house lives here",[2] and a small number of animals live there as well. Workers on watch and administrative personnel of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone are also stationed in the city. The city has two general stores and a hotel.

Etymology

.jpg)

The city's name is the same as one of the Ukrainian names for Artemisia vulgaris, mugwort or common wormwood, which is Ukrainian: чорнобиль, romanized: chornóbyl' (or more commonly полин звичайний polýn zvycháynyy, 'common artemisia').[3] The name is inherited from Proto-Slavic *čьrnobylъ or Proto-Slavic *čьrnobyl, a compound of Proto-Slavic *čьrnъ 'black' + Proto-Slavic *bylь 'grass', the parts related to Ukrainian: чорний, romanized: chórnyy, lit. 'black' and било byló, 'stalk', so named in distinction to the lighter-stemmed wormwood A. absinthium.[3]

The name in languages used nearby is:

- Ukrainian: Чорнобиль, romanized: Chornobyl′, pronounced [tʃorˈnɔbɪlʲ] (

- Belarusian: Чарнобыль, romanized: Charnobyl′, pronounced [t͡ʂarˈnɔbɨlʲ]

- Russian: Чернобыль, romanized: Chernobyl′, pronounced [tɕɪrˈnobɨlʲ].

The name in languages formerly used in the area is:

- Polish: Czarnobyl, pronounced [tʂarˈnɔbɨl]

- Yiddish: טשערנאָבל, romanized: Tshernobl, pronounced [tʃɛrˈnɔbl̩].

History

On the Ptolemy's world map there is the city of Azagarium which, according to "Dictionary of Ancient Geography" of Alexander Macbean (published in 1773 in London), is a town of Sarmatia Europaea on the Borysthenes, 36° East longitude and 50°40' latitude. Now supposed to be Czernobol, a town of Poland, in Red Russia, Palatinate of Kiow (see Kiev Voivodeship), not far from the Borystenes.[4] On the map Azagarium is located on the right bank of Borystenes. It also was located just north of the city of Amadoca which was a capital of Amadocium situated between the lake (palus) of Amadoca (in the west) and the mountains (montes) of Amadoca (in the east).[5]

Chernobyl was originally part of the land of Kievan Rus′. The first known mention of Chernobyl is from an 1193 charter, which describes it as a hunting-lodge of Knyaz Rurik Rostislavich.[6][7] In the 13th century, it was a crown village of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The village was granted to Filon Kmita, a captain of the royal cavalry, as a fiefdom in 1566. The province where Chernobyl is located was transferred to the Kingdom of Poland in 1569, and later annexed by the Russian Empire in 1793.[8] Prior to the 20th century, Chernobyl was inhabited by Ukrainian peasants, some Polish people and a relatively large number of Jews.[9]

Jews were brought to Chernobyl by Filon Kmita, during the Polish campaign of colonization. After 1596, the traditionally Eastern Orthodox Ukrainian peasantry of the district were forcibly converted, by Poland, to the Greek Catholic Uniate religion.[10] Many of these converts returned to Eastern Orthodoxy after the Partitions of Poland.[11]

In 1626, during the Counter-reformation, a Dominican church and monastery were founded by Lukasz Sapieha. A group of Old Catholics opposed the decrees of the Council of Trent. In 1832, following the failed Polish November Uprising, the Dominican monastery was sequestrated. The church of the Old Catholics was disbanded in 1852.[6]

Until the end of the 19th century, Chernobyl was a privately owned city that belonged to the Chodkiewicz family. In 1896 they sold the city to the state, but until 1910 they owned a castle and a house in the city.

In the second half of the 18th century, Chernobyl became a major centre of Hasidic Judaism. The Chernobyl Hasidic dynasty had been founded by Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky. The Jewish population suffered greatly from pogroms in October 1905 and in March–April 1919; many Jews were killed or robbed at the instigation of the Russian nationalist Black Hundreds. When the Twersky Dynasty left Chernobyl in 1920, it ceased to exist as a center of Hasidism.

Chernobyl had a population of 10,800 in 1898, including 7,200 Jews. Chernobyl was occupied in World War I by German forces; Ukrainians and Bolsheviks fought over the city in the ensuing Civil War. In the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–20, Chernobyl was taken first by the Polish Army and then by cavalry of the Red Army. From 1921 onwards, it was officially incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR.[6]

Between 1929 and 1933, Chernobyl suffered from killings during Stalin's collectivization campaign. It was also affected by the famine that resulted from Stalin's policies.[12] The Polish and German community of Chernobyl was deported to Kazakhstan in 1936, during the Frontier Clearances.[13]

During World War II, Chernobyl was occupied by the German Army from 25 August 1941 to 17 November 1943. The Jewish community was murdered during the Holocaust.[6]

Twenty years later, the area was chosen as the site of the first nuclear power station to be built on Ukrainian soil. The Duga over-the-horizon radar array, several miles outside of Chernobyl, was the origin of the Russian Woodpecker; it was designed as part of an anti-ballistic missile early warning radar network. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Chernobyl remained part of Ukraine.

Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster

.jpg)

On 26 April 1986, one of the reactors at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded after unsanctioned experiments on the reactor by plant operators were done improperly. The resulting loss of control was due to design flaws of the RBMK reactor, which made it unstable when operated at low power, and prone to thermal runaway where increases in temperature increase reactor power output.[14][15]

Chernobyl city was evacuated 9 days after the disaster. The level of contamination with caesium-137 was around 555 kBq/m2 (surface ground deposition in 1986).[16][17]

Later analyses concluded that, even with very conservative estimates, relocation of the city (or of any area below 1500 kBq/m2) could not be justified on the grounds of radiological health.[18][19][20] This however does not account for the uncertainty in the first few days of the accident about further depositions and weather patterns. Moreover, an earlier short-term evacuation could have averted more significant doses from short-lived isotope radiation (specifically iodine-131, which has a half-life of about eight days). Estimates of health effects are a subject of some controversy, see Effects of the Chernobyl disaster.

In 1998, average caesium-137 doses from the accident (estimated at 1-2 mSv per year) did not exceed those from other sources of exposure.[21] Current effective caesium-137 dose rates as of 2019 are 200-250 nSv/h, or roughly 1.7-2.2 mSv per year,[22] which is comparable to the worldwide average background radiation from natural sources.

The base of operations for the administration and monitoring of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was moved from Pripyat to Chernobyl. Chernobyl currently contains offices for the State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management and accommodations for visitors. Apartment blocks have been repurposed as accommodations for employees of the State Agency. The length of time that workers may spend within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is restricted by regulations that have been implemented to limit radiation exposure. Today, visits are allowed to Chernobyl but limited by strict rules.

In 2003, the United Nations Development Programme launched a project, called the Chernobyl Recovery and Development Programme (CRDP), for the recovery of the affected areas.[23] The main goal of the CRDP's activities is supporting the efforts of the Government of Ukraine to mitigate the long-term social, economic, and ecological consequences of the Chernobyl disaster.

The city has become overgrown and many types of animals live there. According to census information collected over an extended period of time, it is estimated that more mammals live there now than before the disaster.[24]

Notable people

.jpg)

- Aaron Twersky of Chernobyl (1784–1871), rabbi

- Alexander Krasnoshchyokov (1880–1937), politician

- Arnold Lakhovsky (1880–1937), artist

- Jan Mikołaj Chodkiewicz (1738–1781), Polish nobleman

- Rozalia Lubomirska (1768–1794), Polish noblewoman

- Volodymyr Pravyk (1962–1986), firefighter and liquidator

Climate

| Climate data for Chernobyl, 127 m asl (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.5 (52.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.9 (96.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

36.3 (97.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.7 (−21.5) |

−32.8 (−27.0) |

−20 (−4) |

−9 (16) |

−6 (21) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−20 (−4) |

−30.8 (−23.4) |

−32.8 (−27.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.2 (1.66) |

41.6 (1.64) |

39.0 (1.54) |

46.3 (1.82) |

89.4 (3.52) |

91.6 (3.61) |

106.9 (4.21) |

62.7 (2.47) |

77.4 (3.05) |

56.9 (2.24) |

57.5 (2.26) |

46.3 (1.82) |

757.8 (29.84) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.94 | 10.17 | 7.68 | 9.24 | 11.09 | 12.87 | 12.00 | 8.75 | 11.15 | 8.75 | 10.29 | 10.78 | 122.71 |

| Source: Météo Climat[25][26] | |||||||||||||

See also

References

- Mould, Richard (May 2000). "Evacuation zones and populations". Chernobyl Record. Bristol, England: Institute of Physics. p. 105. ISBN 0-7503-0670-X.

- Withington, John (13 December 2013). Disaster!: A History of Earthquakes, Floods, Plagues, and Other Catastrophes. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-62636-708-1.

- Etymology from O. S. Melnychuk, ed. (1982–2012), Etymolohichnyi slovnyk ukraïnsʹkoï movy (Etymological dictionary of the Ukrainian language) v 7, Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

- Alexander Macbean. A Dictionary of Ancient Geography. London, 1773

- William Smith. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- Chernobyl ancient history and maps.

- Davies, Norman (1995) "Chernobyl", The Sarmatian Review, vol. 15, No. 1, Polish Institute of Houston at Rice University, Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | The Situation of Ethnic Minorities". Refworld. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Serhii, Plokhy (2018). Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780241349038.

- Roudometof, Victor; Agadjanian, Alexander; Pankhurst, Jerry (28 June 2005). Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the 21st Century. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1477-7.

- "The History Place – Genocide in the 20th Century: Stalin's Forced Famine 1932–33". www.historyplace.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Brown, Kate (2004). A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet heartland. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674011686. OCLC 52727650.

- 1957–, Plokhy, Serhii (15 May 2018). Chernobyl : the history of a nuclear catastrophe (First ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9781541617094. OCLC 1003311263.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1970-, Schmid, Sonja D. Producing power : the pre-Chernobyl history of the Soviet nuclear industry. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 9780262321792. OCLC 904249268.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Izrael, Yu A; Cort, M De; Jones, A R; et al. "The atlas of cesium-137 contamination of Europe after the Chernobyl accident". fig. 2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - UNSCEAR (2000). "UNSCEAR 2000 Report Vol. II Annex J Exposures and effects of the Chernobyl accident" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Lochard, J.; Schneider, T.; Kelly, N. (1992). Evaluation of countermeasures to be taken to assure safe living conditions to the population affected by the Chernobyl accident in the USSR. 8. International congress of the International Radiation Protection Association (IRPA8). 36. ISBN 1-55048-657-8. Full conference pdf

- Lochard, J.; Schneider, T.; French, S. International Chernobyl project - input from the Commission of the European Communities to the evaluation of the relocation policy adopted by the former Soviet Union (Technical report). Commission of the European Communities.

- Waddington, I.; Thomas, P. J.; Taylor, R. H.; Vaughan, G. J. (1 November 2017). "J-value assessment of relocation measures following the nuclear power plant accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi". Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 112: 16–49. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2017.03.012. ISSN 0957-5820.

- M De Cort; G Dubois; Sh D Fridman; et al. (1998). Atlas of ceasium deposition on Europe after the Chernobyl accident (PDF) (Report). p. 31. ISBN 92-828-3140-X. OCLC 48391311. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management. "Information on the radiation state of the environment of the exclusion zone". Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- CRDP: Chernobyl Recovery and Development Programme (United Nations Development Program)

- Victoria Gill, 5 October 2015, "Wild mammals 'have returned' to Chernobyl" Archived 17 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (BBC News – Science & Environment)

- "Ukraine climate normals 1981-2010" (in French). Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Weather extremes for Tchernobyl". Météo Climat. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chernobyl. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chernobyl. |

- State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management – official information on public works, zone status, visits, etc.

- Official radiation measurements – State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management. Online map.

- Chernobyl – History of Jewish Communities in Ukraine JewUa.org

- The Chernobyl Gallery