Child labor in Brazil

Child labor, the practice of employing children under the legal age set by a government, is considered one of Brazil's most significant social issues. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), more than 2.7 million minors between the ages of 5 and 17 worked in the country in 2015; 79,000 were between the ages of 5 and 9.[1] Under Brazilian law, 16 is the minimum age to enter the labor market and 14 is the minimum age to work as an apprentice.[2]

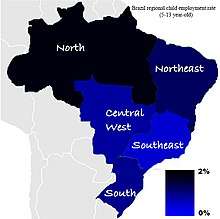

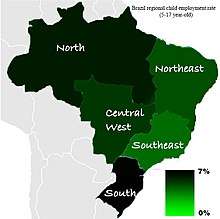

It is estimated that about 30 percent of Brazilian child labor occurs in the agricultural sector, and 60 percent occurs in the northern and northeastern regions of the country. Data indicates that 65 percent of child laborers are Afro-Brazilians, and 70 percent are male.[1]

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), poverty is the leading cause of child labor in the world (including Brazil). Children are forced to work to supplement family income, eliminating their studies and social lives.[3][4]

Since the enactment of the 1988 constitution, child labor has been illegal in the country.[2] The government has taken steps to reduce its prevalence by adopting international conventions and guidelines.

Social movements were created to increase awareness of child labor in Brazil, such as the introduction of the hashtag #ChegaDeTrabalhoInfantil. Other steps included changes to labor laws and increased funding for government welfare programs, such as Bolsa Família, which support impoverished families.[3][4] As a result, the number of underage workers fell from about eight million in 1992 to five million in 2003.[4]

Despite these improvements, Brazil still accounts for one-fourth of Latin America's underage workers in. Between 2014 and 2015, there was a 13-percent increase in the number of reported child workers under age 10.[1] In 2016, there were 1,238 cases of child exploitation recorded in the public prosecutor's office.[1] However, many instances of child labor in the informal economy (such as child prostitution or drug trafficking) went unrecorded.[5]

Definitions

Brazilian definition and regulation

In Brazil's constitution, child labor is addressed in Article 7, Item 33. The item prohibits night work and any work considered "dangerous or unhealthy" for youth under 18. Minors under age 16 are not allowed to work, except for apprenticeships for minors over 14 years old.[6][7]

International definitions

Child labor, according to the ILO,[8] is "work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development." It refers to work which can damage children mentally, physically, socially, or morally; work depriving children of the ability to attend school, or work which places heavy burdens on them in addition to schoolwork. The definition of child labor largely depends on the working environment, the legal working age and the type of work done. The organization defines child slavery, child prostitution, child crime (such as drug trafficking) and any work jeopardizing the safety of children as the worst forms of child labor.[8]

UNICEF has different criteria for child labor. For children between 5 and 11 years old, work is categorized as child labor if at least one hour of economic activity or at least 28 hours of domestic work is performed weekly. For children between 12 and 14 years of age, 14 hours or more of economic activity or 42 hours of economic activity and domestic work per week constitute child labor.[9]

History

Child labor has been part of Brazilian history since 1500. Because the notions of youth or childhood were not well defined until the middle of the nineteenth century in the country, however,[10] there was limited information on child labor before the 20th century.[5] Early documentation of Portuguese ships included evidence of minors working in the 16th century on sea voyages for immigrants from Portugal and other parts of Europe.[11] Although children did domestic work before the arrival of European settlers, the degree of child labor in Brazil worsened drastically after the Europeans' arrival.[12] The first organization to use minors for labor was the Brazilian Navy during the Paraguay War,[5] and data indicates that over 600 children aged nine to 12 were on the battlefield.[13] This involvement with the military and contact with weapons were some of the worst forms of child labor seen in Brazil. Children in favelas are desirable middlemen in drug trafficking, since their minor status makes them immune from prosecution.[14] Children were used widely for labor during the slavery period on sugar plantations.[15] Slaveholders embraced the idea of making the children of slaves work, since overall productivity increased without the purchase of more slaves.[16]

Industrialisation in Brazil, beginning in the late 19th century, replaced slavery in exploiting children. Capitalists would hire minors, since there were no laws regulating child labor and children were perceived as costing less. In São Paulo, with widespread industrialization and a corresponding demand for workers, textile factories published advertisements recruiting children in the mid-1870s.[17] Most of São Paulo's working class consisted of poor immigrants, and some families depended on their children's work.[13] In 1890, 25 percent of São Paulo's textile labor force was made up of children;[5] in 1865 Rio de Janeiro, 64 percent of workers in a textile factory were children.[18] Children were injured or killed by the harsh work, poor working conditions, and violent treatment by their bosses. Armando Dias, a child worker in the textile industry, was electrocuted in November 1913.[13] When teenager Francisco Augusto de Fonseca did not perform his job to the owner's expectations, he was brutally struck on the face.[13] Child labor during this period was seen as a necessity; capitalists exploited the low cost of minor workers to suppress adult workers' wages, and poor families needed their children to work.[5]

Attempts to protect children's rights and regulate child labor began during the late 19th century,[5] and an 1891 decree concerned minor employees in the factories of Brasília.[19] The Brazilian Labour Confederation, which advocated restrictions on child labor, was founded in 1912.[20] Five years later, workers in São Paulo went on strike; their demands included the abolition of night work for workers under age 18 and all work for children under 14. In 1919, a city law set the legal working age at 14 years old. Constitutional amendments in 1934, 1937, and 1946 prohibited work by minors under 14. The 1964–1985 military dictatorship in Brazil, however, lowered the minimum working age to 12. Constitutional amendments in 1988 and 1998 and a 2000 law in 2000 are the present legal definition of child labor: hazardous work by minors under 18 and any form of labor by minors under 16. Apprenticeships are permitted at age 14.[5]

On February 2, 2000, the government ratified ILO convention 182.[21] On June 28 of that year, the Brazilian government ratified ILO convention 138.[22]

Present day

The Brazilian government has prioritized the eradication of child labor.[23] The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics began conducting the annual Brazilian National Household Sample Survey (PNAD) in 1981, which provides data on child-labor reports by region. In 2005, over 2.9 million children under age 17 engaged in some form of labor (7.8 percent of the age group).[5]

The 2016 survey indicated that 4.6 percent of children aged 5–17 (1.8 million out of 30 million) were working, an improvement over 2005. In 2016, most child labor was found in the 14–17 age group. Two-tenths of one percent of the 5–9 age group was working, 1.3 percent of the 10–13 age group, 6.4 percent of the 14–16 age group and 17 percent of the 16–17 age group. The persistence of child labor varies by region. The North and South Regions have the highest child-labor rates (5.7 and 6.3 percent, respectively). For children under 14, the North and Northeast Regions have the highest rates (1.5 and one percent, respectively). Racially, the black and brown (preta e parda) population makes up 64.1 percent of child labor; 35.9 percent are white (branca). Boys make up 65.3 percent of child workers. Of child laborers aged 5–13, 47.6 percent are agricultural workers; 21.4 percent of laborers aged 14–17 are farm workers. Although some agricultural work is performed as part of the vocational-training process, other children are forced to work in agriculture to supplement family income.[24]

Despite the gradual decrease in child labor, it is still prevalent (including hazardous occupations). In the agricultural sector, children fish, harvest molluscs, and produce rice, soybeans, tobacco and charcoal.[25] In industry, children work in quarries,[26] produce bricks[27] and slaughter animals.[28] In the service sector, children do street work such as garbage collection[29] and sometimes sell alcohol.[30] Children are forced to work for criminal gangs[31] or engage in prostitution.[32][33] Child sex tourism is common in coastal areas which attract tourists, and girls from other South American countries are sex workers in Brazil.[32] Efforts to further reduce child labor are working towards Sustainable Development Goal 8, which "promotes sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all."[34]

Legal framework

| Standard | International-standard compliance[35] | Age | Legislation | Enacted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum legal working age | Yes | 16 | Labor Code: article 403[36] | May 1, 1943 |

| Minimum age for hazardous work | Yes | 18 | Hazardous Work List: article 2[37] | June 12, 2008 |

| Prohibition of forced labor | Yes | Penal Code: articles 149 and 149-A[38] | Dec 7, 1940

Oct 6, 2016 | |

| Prohibition of child trafficking | No | Penal Code: article 149-A;

Child and Adolescent Statute: article 244A[39] |

Oct 6, 2016

July 13, 1990 | |

| Prohibition of commercial sexual exploitation of children | Yes | Penal Code: articles 218-A 218-B, and 227–228[38] Child and Adolescent Statute: articles 240–241 and 244A[39] | Dec 7, 1940

July 13, 1990 | |

| Prohibition of child involvement in illicit activities | Yes | National System of Public Policies on Drugs: articles 33 and 40[40] Child and Adolescent Statute: article 244-B | Aug 23, 2006

July 13, 1990 | |

| Prohibition of military recruitment | ||||

| State compulsory | Yes | 18 | Military Service Law: article 5[41] | Aug 17, 1964 |

| State voluntary | Yes | 17 | Military Service Regulation: article 127[42] | Jan 20, 1966 |

| Compulsory education age | Yes | 17 | National Education Law: article 4[43] | Dec 20, 1996 |

| Provision of free education | Yes |

The Ministry of Labour (MTE) is in charge of labor-law enforcement. Its responsibilities include child-labor inspections, enforcing child-labor laws and dispatching inspection teams (inspectors, prosecutors, Federal Police officers and other law-enforcement officials) to sites where child labor is suspected.[44] However, gaps in MTE operations hinder full enforcement of labor laws. Although 7,491 child labor inspections were conducted in 2017, insufficient funding limits the inspection abilities of regions with no local MTE offices.[45] In July 2017, inspectors were prevented from conducting child-labor inspections in the states of São Paulo and Rio Grande do Norte.[46]

Government policies

National Plan to Combat Sexual Violence Against Children and Adolescents (2013–2020)

The plan reaffirms Brazil's commitment to defend the rights of children and adolescents, especially those in threatening situations where fundamental rights are violated. It "identifies strategies to prevent the sexual exploitation of children, protect children’s rights, and assist child victims".[35] The plan's goals include:

- Ensuring preventive action against abuse or sexual exploitation of children and adolescents, primarily through education, awareness and self-defense

- Ensuring specialized assistance to children and adolescents in situations of sexual abuse or exploitation by trained, specialized professionals, and ensuring care for perpetrators of sexual violence while respecting ethnic-racial condition, gender, religion, culture and sexual orientation

- Updating the regulatory framework on sexual crimes and providing skilled reporting and accountability

- Promoting the active participation of children and adolescents in the defense of their rights in the development and implementation of protection policies

- Strengthening national joint regional and local elimination of abuse or sexual exploitation in media, networking, forums, commissions and councils

- Understanding the expressions of abuse or sexual exploitation of children and adolescents through diagnostics, data collection and research[47]

National Plan for the Eradication of Forced Labor

Forced labor is an integral part of the child-labor issue in Brazil. Some children are forced to do domestic work; others are forced to produce coffee and manioc.[48] The current version of the National Plan for the Eradication of Forced Labor, introduced in 2008, establishes its policy framework. The plan's goals include:

- Keeping the eradication of forced labor a priority

- Establishing integrated strategies for executive bodies, prosecutors and civil society

- Creating and maintaining a database of information about key players in the fight against forced labor to assist in prevention and drafting laws

- Providing national and regional mobile inspection teams in sufficient numbers to meet the complaint and inspection demands[49]

National Education Plan (2014–2024)

Education is believed to be one of the best solutions to child-labor issues.[50] The National Education Plan is a demonstration of the government's determination to improve the quality and accessibility of education. The plan has 20 goals encompassing basic education for children, and aims to promote the quality of higher education; goal 14 intends to gradually increase the number of students in graduate school.[51]

Social programs

Social programs aim to address child labor in Brazil directly or indirectly. Some are funded by the government, such as Bolsa Família (a family welfare program introduced during Lula's presidency). Others are on social media, such as #ChegaDeTrabalhoInfantil (#stopchildlabor).

National Program to Eradicate Child Labor

This program aims to remove children and adolescents under age 16 from early work, excluding apprenticeships at age 14.[52] In addition to ensuring income to families, it includes children and young people in counseling and follow-up services. School attendance at school is required. The program is run by the Ministry of Social Development.[52] The federal government pays a monthly stipend of R$25 per child to families who withdraw the child from the workforce in areas with a population under 250,000, and R$40 per child in areas with a population of 250,000 or above. The family must ensure school attendance greater than 85 percent to receive the grant.[53]

Bolsa Família

Bolsa Família is a government social-welfare program which is part of the Fome Zero network of federal-assistance programs. Providing financial aid to poor Brazilian families, conditions of the program are that families ensure school attendance and vaccination for their children. If they exceed the number of permitted school absences, they are dropped from the program and their funds are suspended. In 2017, 93.1 percent of children ages 6–15 had 85-percent school attendance; 82.3 percent of 16– and 17-year-olds met the minimum attendance requirement of 75 percent.[35] Studies suggest that the program has improved girls' school participation and educational performance, but has had little effect on boys.[54]

#StopChildLabor campaign

In 2017, the Ministry of Labour (MPT) began a campaign with the hashtag "#StopChildLabor" encouraging Internet users on social networks to post the hashtag in opposition to child labor. The campaign was supported by celebrities, including musicians Daniel, Chitãozinho and Xororó, former volleyball player Maurício Lima and former basketball player Hortência Marcari.[55]

| Name | Administration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Living Together and Strengthening Links (SCFV)[56] | Ministry of Social Development | Provides age-appropriate group artistic, cultural, leisure and sports activities, challenging, stimulating and guiding vulnerable groups in building and rebuilding their individual, group and family experiences |

| National Program for Job Training and Employment[57] | Ministry of Education | Expands vocational and technological education (EPT) courses with programs, projects, and technical and financial assistance. High-school students are included. |

| South–South cooperation | "In 2017, the government hosted representatives from six countries to discuss ILO’s child-labor prediction model and the PETI program redesign."[35][58] |

References

- Braziliense, Correio (2017-06-11). "Trabalho infantil atinge 2,7 milhões de crianças e adolescentes no Brasil". Correio Braziliense (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- "Brasil registra aumento de trabalho infantil entre crianças de 5 a 9 anos". Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- "Convenções da OIT intesificam combate ao trabalho infantil | BBC Brasil | BBC World Service". BBC. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- "Tire suas dúvidas sobre trabalho infantil no Brasil". BBC. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- Child labour's global past, 1650–2000. Lieten, Kristoffel, Nederveen Meerkerk, Elise van. Bern: Peter Lang. 2011. ISBN 9783035102185. OCLC 811259893.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "O trabalho infantil no Brasil". DireitoNet (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Article 7, Clause 33 of the Constitution of Brazil (1988)

- "What is child labor (IPEC)". ilo.org. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- "UNICEF – Definitions". unicef.org. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- Gutiérrez, Horácio; Lewkowicz, Ida (1999). "Trabalho infantil em Minas Gerais na Primeira metade do século XIX". Locus – Revista de História (in Portuguese). 5 (2). ISSN 1413-3024.

- Pestana Ramos, Fábio (1999-01-01), A História Trágico-Marítima das crianças Nas embarcações portuguesas do século XVI., pp. 19–54, ISBN 8572441123, retrieved 2018-10-08

- Boas práticas : combate ao trabalho infantil no mundo. International Labour Office., Brazil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome., Brazil. Ministério do Trabalho e Emprego., Brazil. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Brasília: DF. 2015. ISBN 9788560700868. OCLC 930464628.CS1 maint: others (link)

- História das crianças no Brasil. Del Priore, Mary. São Paulo, SP: Editora Contexto. 1999. ISBN 8572441123. OCLC 43628836.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Veloso, Leticia (2012-10-01). "Child Street Labor in Brazil: Licit and Illicit Economies in the Eyes of Marginalized Youth". South Atlantic Quarterly. 111 (4): 663–679. doi:10.1215/00382876-1724129. ISSN 0038-2876.

- Combatendo o trabalho infantil : guia para educadores. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour., Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas em Educação, Cultura e Ação Comunitária. (1st ed.). São Paulo, SP, Brasil: CENPEC-Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas em Educação, Cultura e Ação Comunitária, Programa Internacional para a Eliminação do Trabalho Infantil, IPEC, Organização Internacional do Trabalho, Escritório no Brasil. 2001. ISBN 9228110406. OCLC 48214253.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Child Labour's Global Past, 1650–2000". eds.b.ebscohost.com.

- Moura, Esmeralda (1982). Mulheres e menores no labor industrial: os fatores labor e idade na dinâmica do capita.

- 1952–, Foot, Francisco (1991). História da indústria e do trabalho no Brasil : das origens aos anos 20. Leonardi, Victor, 1942– (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Editora Atica. ISBN 8508037562. OCLC 27266945.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Campos, Herculano Ricardo (2001). "TRABALHO INFANTIL PRODUTIVO E DESENVOLVIMENTO HUMANO". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dulles, John W. F. (1977). Anarquistas e comunistas no Brasil: 1900–1935 (in Portuguese). Nova Frontera.

- "Ratifications of ILO conventions: Ratifications by Convention". ilo.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Ratifications of ILO conventions: Ratifications by Convention". ilo.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Trabalho Infantil no Brasil". Toda Matéria (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- "PNAD Contínua – Trabalho Infantil". loja.ibge.gov.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- O Trabalho Infantil no Brasil. ABRINQ Foundation. 2017.

- "Globo Repórter mostra imagens de trabalho infantil no estado do Piauí". redeglobo.globo.com (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- "Não é brincadeira: O trabalho infantil que Santa Catarina não vê". agenciaal.alesc.sc.gov.br. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Despite Strict Laws, Child Labor in Brazil Is Not Going Away". Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Treaty bodies Download". tbinternet.ohchr.org. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Trabalho infantil no Nordeste perpetua o ciclo da pobreza e miséria". opovo.com.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Traficantes cariocas recrutam e armam crianças cada vez mais novas para o crime". epoca.globo.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- des Hommes, Terre (May 9, 2014). "Sexual Exploitation of Children in Brazil: Putting a Spot on the Problem" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 10, 2018.

- "Alejandra: Girl, 14, in Brazil's child prostitution epicentre". news.com.au. 2018-08-10. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- "Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth | UNDP". UNDP. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Brazil". United States Department of Labor. 2016-09-30. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del5452.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2008/Decreto/D6481.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "L13344". planalto.gov.br. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8069.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11343.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "L4375". planalto.gov.br. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/d57654.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - planalto.gov.br http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm. Retrieved 2018-10-11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Página inicial". trabalho.gov.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Trabalho Infantil nos ODS. Fórum Nacional de Prevenção e Erradicação do Trabalho Infantil (FNPETI). 2017.

- "Ministério do Trabalho nega pedidos de fiscalização por falta de recurso, diz MPT". O Globo (in Portuguese). 2017-07-26. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Plano Nacional de Enfrentamento da Violência Sexual contra Crianças e Adolescentes. (2013)http://www.crianca.mppr.mp.br/arquivos/File/publi/sedh/08_2013_pnevsca.pdf

- "Treaty bodies Download". tbinternet.ohchr.org. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- "2º Plano Nacional para a Erradicação do Trabalho Escravo" (PDF). Conselho Nacional de Justiça. 2008.

- "Educação é fundamental para combater trabalho infantil". unric.org (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2018-10-14. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- Ministério da Educação. Planejando a Próxima Década – Conhecendo as 20 Metas do Plano Nacional de Educação. 2014http://pne.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/pne_conhecendo_20_metas.pdf

- http://www.chegadetrabalhoinfantil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/comissao-municipal-do-peti.pdf

- "PETI – Programas Sociais | Caixa". caixa.gov.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- de Brauw, Alan; Gilligan, Daniel O.; Hoddinott, John; Roy, Shalini (June 2015). "The Impact of Bolsa Família on Schooling". World Development. 70: 303–316. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.02.001. ISSN 0305-750X.

- "MPT lança campanha contra à exploração do trabalho infantil". Justificando (in Portuguese). 2017-06-09. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- "Convivência e Fortalecimento de Vínculos". mds.gov.br/.

- "Pronatec" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- "Brasil e outros seis países latino-americanos testam ferramenta estatística sobre trabalho infantil". ONU Brasil (in Portuguese). 2017-09-20. Retrieved 2018-10-14.