Chief Secretary's building

The Chief Secretary's building (originally the Colonial Secretary's building) is a heritage-listed[1][2] state government administrative building of the Victorian Free Classical architectural style located at 121 Macquarie Street, 65 Bridge Street, and at 44-50 Phillip Street in the Sydney central business district of New South Wales, Australia. The ornate five-storey public building was designed by Colonial Architect James Barnet and built in two stages, the first stages being levels one to four completed between 1873 and 1881, with Walter Liberty Vernon completing the second stage between 1894 and 1896 when the mansard at level five and the dome were added.[1]

| Chief Secretary's building | |

|---|---|

Bridge Street façade of the Chief Secretary's building | |

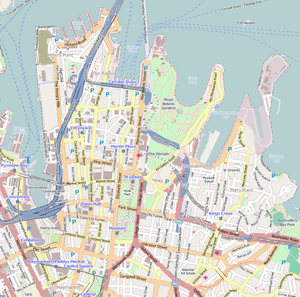

Chief Secretary's building Location in greater Sydney | |

| Former names | Colonial Secretary's building |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Government administration |

| Architectural style | |

| Address | 121 Macquarie Street, Sydney, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°51′49″S 151°12′44″E |

| Current tenants | |

| Construction started | 1873 |

| Completed | 1886 |

| Opened | 1881 |

| Cost |

|

| Renovation cost | A$32 million (2005) |

| Client | Colonial Secretary of New South Wales |

| Owner | Government of New South Wales |

| Technical details | |

| Material |

|

| Floor count | 5 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect |

|

| Architecture firm | Colonial Architect of New South Wales |

| Developer | Government of New South Wales |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect | Government Architect's Office |

| Awards and prizes |

|

| Official name | Chief Secretary's Building; Colonial Secretary's Building |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., c., d., e., f. |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 766 |

| Type | Other - Government & Administration |

| Category | Government and Administration |

| References | |

| [1][2][3] | |

The sandstone building was the seat of colonial administration, has been used continuously by the Government of New South Wales, and even today holds the office of the Governor of New South Wales. Its main occupant is the Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales; several of the larger rooms are now courtrooms.

...(this) pile of a building like a veritable 'poem in stone' adorns the northern portion of Macquarie Street.

— Illustrated Sydney News, 28 February 1891

History

In 1856 New South Wales was a granted responsible government. This important step in self government brought with it a number of new portfolios requiring new office space as well as a greater need for the departmental head and his staff to be located in approximately the same space. At this time the several departments were located in a number of buildings some hired and some still housed in the domestic buildings constructed in the earliest days of the colony.[1]

During the later years of the nineteenth century, while some former responsibilities were removed from the authority of the Colonial Secretary, it remained a pre-eminently prestigious and important political position. The Premier and the Colonial Secretary were usually one or, in coalition governments where the Premier chose another portfolio, such as Lands, the post of Colonial Secretary usually was held by the head of the coalition party.[1]

It was against this high-profile role of the Colonial Secretary as well as the expansion of that and several other departments and the escalating costs of rental properties such as those in Phillip and Young Streets and that the construction proposal and plans were formed for the new building for the Chief Secretary. The site of the building was highly symbolic of the elevation in status of the office. Further up Bridge Street, it formed a significant element of the most important political and administrative offices. In close proximity to Government House, the gates to that residence being across the road, it was in close to Parliament House and overlooked the Treasury Building. Its position halfway between Parliament and Government House, was both practical and illustrative of the respective relationships of those offices.[1]

From 1860s to 1890s

By 1869 sufficient finance had been raised to construct a new and worthy building for the office of the Chief Secretary of the colony as well as providing offices for the Works Department. James Barnet, the Colonial Architect, designed an impressive multi-storied building to occupy the six lots in an "L" shaped portion of the block fronting bridge Street in the period. The drawings were prepared in the period of July 1869 to mid 1870. For this work Barnet was paid nineteen pounds and ten shillings.[1]

The first tender for the work, excavation and masonry, was let in 1873 to the McCredie Brothers. However, by mid 1874, only a little over £3,000 had been spent out of an estimated £60,000 expenditure. By mid-1875 over £15,500 had been spent on the new building. By this time tenders had been let for marble and timber floors. By mid 1876 the expenditure on the building had risen to £33,128 and by mid-1877 to £52,424. By 1878 it was obvious that the building was going to considerably exceed the original estimates for its construction costs. By June of that year over £76,000 had been spent, £16,000 above the original estimate. This figure did not encompass the thirty-five thousand pounds it was estimated would be required for the finishing trades.[1]

The last works on the buildings included the commissioning and erection of statues by Giovanni Fontana and the completion of the finishing trades. In 1880 it was reported that work on the Colonial Secretary's building was completed at a final cost of £81,558/19/1 It was noted, though, that the finishing trades were still ongoing at that time, having spent over 42,620 pounds upon them. These works were completed the following year. As early as 1882 alterations, their extant and nature unknown, were carried out in the building to a cost of £992. It is clear that, as the various officials and their departments took possession of their new quarters, a period of settling in and adjustment was required for the building. More alterations were required in 1883 at a cost of £11,037 and in 1884 for £760. From 1885 to 1888 repairs of apparently a minor nature were required.[1]

The modifications made to the building in the first years of its existence suggest that the original plan was not comprehensive in addressing the needs of the various departments that were to occupy it. By the end of the 1880s space within the building was at a premium. Several of the occupants complained to the effect that, despite the construction of the building, they were in little better situation than had been the case prior to its existence. The Commissioner for Roads complained that he was inconvenience having so many officers so far away. The Engineer-in-Chief for the Harbours and River complained that he had insufficient office accommodation and the Acting Engineer-in-Chief for Railways complained that he lost time because his staff were so widely distributed in various offices. The only option was to extend the ten-year-old building.[1]

In November 1889 the Acting Engineer-in-Chief prepared a sketch of a proposed extension to the existing Chief Secretary's building. It encompassed a building of six storeys fronting Phillip Street to 18 metres (60 ft) with a depth of 31 metres (102 ft) and a lane at the back. The building was designed to house the Railway Commissioners and the clerical staff of the public Works Department on the ground and first floors. The principal consideration for the new building was economy. The Acting Engineer-in-Chief pointed out that the work was to be done quickly, the tenders let as soon as possible and the project to be kept under £20,000. By February 1890 an estimate of just over £18,000 had been prepared for the work. Tenders were called in March of the same year for the resumption of the terrace houses and yards that occupied the site of the proposed extension to the building. The tender for what became known as the first contract, the six storey building, was let in April 1890. By mid-1890 the expenditure on the new building amounted to £15,603 while alterations and repairs in the existing structure came to over £877. In July 1890, while work continued on the first extension to the Chief Secretary's building, approval was given for the construction of an extension to this only partially constructed building.[1]

From 1890s to 1990s

This extension was considered necessary largely because of the needs of the Public Works Department. The new building generally was designed to house that department and would free the Board room of the office which was then occupied by the Public Works Committee. The extensions comprised a new range that was to connect to the southern line of the new building having a frontage of 13 metres (43 ft) to Phillip Street and an eastern extension to the lane of 10 by 6 metres (32 ft × 20 ft). The cost of this new work was estimated to be £14,136 and it involved the resumption and demolition of more terraces along Phillip Street. The tender for the second contract was let in September 1890. A further modification to the work was the decision to link the new (and extended) building to the existing building by means of a more substantial link than the originally designed iron footbridges. Eventually it would be a five-storey addition. By mid-1891 the land required to be resumed for the new work had been bought at a cost of £25,725 and expenditure on the additions under construction amounted to £14,869. As well, over £1,000 had been spent on alterations and repairs in the existing building. Despite this massive outlay consideration was given to yet a third extension to the south of the new wing or, more precisely, what measures could be taken to avoid this additional project. This was investigated by Vernon because even with the additional work the Public Works Department could not be accommodated in the building.[1]

To avoid a costly solution, Vernon proposed raising the height of the existing building to create virtually two new floors. Vernon was concerned that the vertical addition to the building would imbalance it in relation to the Bridge Street elevation. Vernon estimated would cost approximately £12,000 although savings were to be made by substituting a less expensive timber and slate roof for the concrete dome roof than in the contract. Fallick and Murgatroyd were contracted to carry out the new stage of work. By mid-1892 £45,097 had been spent on the various works which were finally completed in 1893 for a total cost of £54,926/2/9.[1] Fire had always been a constant worry and therefore an extensive Mansard roof and central dome was added providing additional accommodation and adding to the architectural completeness of the building.[1]

For the few final years of the nineteenth century and for most of the following twentieth century work within the Chief Secretary's Building was confined to altering and adding as the need arose. There were no planned programs of extension or renovation. The interiors of the building began to reflect this ad hoc approach to office accommodation which in turn illustrate the changing roles of the various departments housed within the building. Minor alterations, particularly the provision of ladies lavatories, demonstrate a changing pattern with the workforce that serviced the departments. The period of the 1920s was the most active in terms of work carried out on the building. Plans were prepared for a private stair for the Minister for Health in 1920, for a roof over the bridge connecting the old and new buildings in 1924, extensions to the ladies room on the ground floor in 1927 as well as several other minor conversions and alterations. After World War II improvements were made to the building to bring it in line with modern standards and requirements. The construction of the State Office Block in the 1960s and the subsequent relocation of the Public Works Departments there allowed the Chief Secretary's building to be renovated and re-used for several new purposes.[1]

Through the later 1960s and to 1971 the Chief Secretary's Building underwent major changes to accommodate new occupants principally the Divorce Courts, including accommodation for judges, the Opera House Trust, the Commissioner for Western Lands and the Valuer General's Department. By the 1980s the value of the building had come to be appreciated as a significant item of the city's environmental and historic landscape. To this end, as a bicentennial project, a million dollar project was set in motion to restore the stonework of the building. This work was completed in 1990 at a cost of approximately A$2 million dollars.[4][1]

Description

In its existing configuration the Chief Secretary's Building consists of two major directly linked components. At Macquarie, Bridge and Phillip Streets - a four-storey sandstone building, with a copper and slate roof mansard and a copper clad dome. At Phillip Street - a five-storey sandstone building with copper roofed mansards.[1]

The original building was designed by Barnet in what is now called the Victorian Free Classical style; characteristics of this style are the massive basement wall with superimposed classical orders and circular arched openings, wide arcaded balconies and balustraded parapets behind which are the barely visible low pitched hipped roofs. When Vernon added to and extended this building he chose the somewhat different, though related, Victorian Second Empire style, the chief characteristics of which can be seen in the iron crested mansard roofs and the pavilion dome.[1]

Barnet adopted a scheme of decoration that involved variations from floor to floor and a further variation within each floor. The most ornate decoration was given to all corridors and entrances, principal room located at the four corners of the building on levels 2 and 3, large rooms at the centre of the bridge Street elevation on levels 2 and 3. Decreasing ornateness was given to the spaces along the Bridge Street elevation, between principal rooms on levels 2 and 3. Austere, simple decoration was given to the range of rooms facing south into the Phillip Lane courtyard.[5][1]

Architecture

Constructed 1873-1880, the building was designed by colonial architect James Barnet. Its style has been called "Venetian Renaissance" as well as Victorian Free Classical. A fifth floor and dome were added in the 1890s by Barnet's successor Walter Liberty Vernon in the Victorian Second Empire style,[6] as well as an extension south at 50 Phillip Street. Barnet resented the additions, which lessened the resemblance to his model, the 16th-century Palazzo Farnese in Rome, completed by Michelangelo after Farnese became Pope Paul III. The dome was originally covered in aluminium in 1895-1896, one of the earliest such uses of this metal in the world.

The building features nine life-size statues (six external and three internal) placed according to the administrative function of three parts of the building. The entrances on three streets are labelled in sandstone, directing visitors to the appropriate section.

- The prestigious 121 Macquarie Street entrance is labelled "Colonial Secretary". He occupied the North-East corner office on the First Floor (at the time the top floor, now called Level 3). Sandstone sculptures in the building's exterior personify Mercy, Justice, and Wisdom (top to bottom). Inside stands a marble statue of Queen Victoria.

- The 65 Bridge Street (central) ground floor entrance, one level below, is labelled "Public Entrance". Inside stands a female figure representing New South Wales, a merino at her foot. The NSW Badge, adopted in 1876, is sculpted above in the pediment.[1]

- The 44 Phillip Street entrance is labelled "Secretary for Works" and features a bust of Queen Victoria. The Minister for Public Works had his office in the North-West corner. The external statues personify Art, Science, and Labour. The internal statue on this side is of Edward VII when Prince of Wales.

The internal Carrara marble statues are by Giovanni Giuseppe Fontana. He was born in Italy (1821) but lived and worked in England, dying in London in December 1893. The external sandstone statues are by Achille Simonetti (Rome 1838 - Birchgrove 1900), who in 1874 established a large studio in Balmain.[7]

The interior features Australian Red Cedar and ornate tiles, plaster ceilings and cornices.

The building's design and furnishings reflect in large part the taste of the first Colonial Secretary, Sir Henry Parkes.

The Executive Council Chamber (originally known as the Cabinet Room) was the venue for several meetings that led to Federation, including the Australasian Federal Convention of 1891.[8] The room is very well preserved, with period furniture, paintings of a young Queen Victoria and James Cook, and bronzes of several British Prime Ministers including Palmerston. Some of the objects on display were acquired from the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition.

Extensive restorations between 1988 and 2005 were performed with a degree of care that set new standards.[9][10] It is open to the public; several historical displays interpret the building's history, and the glass lift shafts allow archaeological viewing of the construction.

Condition

As at 30 October 1997, Physical condition is good. Archaeological evidence of the most eastern extension of First Government House may be located under the street and footpath to the west of the Chief Secretary's building.[11][1]

Modifications and dates

The original building comprises levels 1 to 4 was constructed between 1873 and 1881. In 1894-96 the mansard at level 5 and the dome were added.[1]

The Phillip Street additions were built in four major stages over the period 1890-1893.

- Stage 1 : 3 bay width, levels 1-6.

- Stage 2 : Infill over Phillip Lane, Levels 2-5.

- Stage 3 : 2 bay width, Levels 1-6.

- Stage 4 : Mansard increased in height, Level 6.[1]

Other alterations included:

- Before 1897 - Room added on level 2 & 3 of original building.

- 1914 - formation of Governor's Suite, Level 2 of original building.

- 1920 - Insertion of timber stair, level 1 to level 2, north-east corner of original building.

- 1942 - conversion of Bridge Street lift from hydraulic to electric operation.

- Between 1896 and 1970 - refer to conservation plan for detailed analysis.

- April 1967 - the Department of Public Works relocated from the Chief Secretary's Buildoing to their new headquarters in the State Office Block. Major alterations to interiors occurred on all levels and safety aspects improved.

- After 1970 - the original latrine block in the middle of the courtyard was demolished and the pre-1897 additional rooms on levels 2 & 3 of the original building were demolished. The building was entirely re-roofed and the sandstone facaed cleaned.[12][1]

Heritage listing

The Chief Secretary's building is of national significance by reason of its historic, social, architectural, aesthetic and scientific values. It embodies, by its construction for and association with, pre-eminently important office and department of the Colonial, later Chief Secretary. This most enduring of political and administrative institutions achieved, through its expansion and growing politicisation, the most far reaching powers of any of the administrative departments of the Colonial bureaucracy. The decisions made in this department affected every level of society in the colony.[1]

After the institution of responsible government in 1856 the office of the Chief Secretary was almost continuously held until the twentieth century by the Premier of NSW further underlining its important role. Several outstanding figures in NSW political life held this office and through it, and the role of the Premier, were able to campaign for the most important political agendas of the time, including, but not exclusively, economic and land reform and Federation.[1]

The locations, size and lavish treatment graphically demonstrate the importance of the departments that were housed there, the social hierarchy of its occupants as well as the practical workings of the fully developed late nineteenth century bureaucracy. The interior finish demonstrates refinement of public taste. Its continual occupation as government offices through to the twentieth century make it possible to demonstrate, through changes made to the fabric, changing community practices such as greater opportunities for women in the workforce.[1]

The building is one of the most significant late nineteenth century architectural works in Sydney. It embodies two of the most significant projects of Barnet and Vernon and was ranked, by contemporary accounts, with pre-eminent public works of the time such as the GPO. It remains a dominant element in the Victorian streetscapes of this part of Sydney.[1]

Its placement in relation to Government House, Parliament House, the Treasury Building and other major departmental offices symbolises the relationship to the office to both political and public offices.[13][1]

Chief Secretary's building was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The building embodies, by its construction for and association with, pre-eminently important office and department of the Colonial, later Chief Secretary. The position of Chief Secretary was one of the most enduring political and administrative institutions in the country. The earliest incumbent of the office, or the position that would evolve into that office, was appointed in 1788.[1]

Through its expansion and growing politicisation during the first half of the nineteenth century, it achieved the most far reaching powers of any of the administrative departments of the colonial bureaucracy. The decisions made in this department affected every level of society in this colony.[1]

The importance of the office is emphasised by the almost continuous responsibility for this portfolio taken by successive Premiers of NSW after the institution of responsible government in 1856. This link between the chief political office and administrative department was not to be broken until the middle years of the twentieth century. The office space afforded for ministerial occupation illustrates this link as does the Executive Council Chamber.[1]

Because of the dual political/administrative connections of this office it was associated with several outstanding and prominent figures in both the social and political life of NSW and, because of the significance of that state, Australia. Henry Parkes, Charles Cowper and Hohn Robertson were some of the prominent incumbents of the office.[1]

Through the association of the office with these figures it has come to be associated with dominant political and social agendas of the nineteenth century. Federation, economic and land reforms may be counted amongst those. The position provided its occupant a prominent platform from which he could campaign for these and other issues although the office should not be misinterpreted as providing a focus for specific agendas. Each, including Federation, was achieved through the work of several key individuals and work, forums and conventions in several places throughout Australia. It was the workings of this office and its connections that made those agendas possible.[1]

This building is historically significance because it demonstrates through its location, size and lavish treatment the evolution in importance of this particular department and that of the Public Works Department. It replaced a two-storey essentially domestic structure which had housed those two departments since 1813. The magnitude of the building, particularly in comparison to its predecessor, illustrates not only the growth of the department but also the prestige attached to it.[1]

The location of the building is historically significant. It forms a particularly important component in an area that, since its election for the site of First Government House, has been associated with the upper echelons of political and administrative life in the country. It has close physical proximity to (second) Government House, the NSW Parliamentary buildings and the principal offices of the main departments, Treasury, Lands and Education.[1]

The building is of historical importance because of its demonstration of the fully developed nineteenth century public service and the practical workings of that bureaucracy. The internal plan layout, individual spaces and degree of elaboration of finishes demonstrate the dual hierarchy of its users as well as the specific departmental organisation. It is a rare, though not unique, example of such offices on this scale.[1]

The additions made to the building in the 1890s for Public Works not only demonstrate the increasing needs and specialisation of that department after its reorganisation, and the inadequacy of the original design to meet theses needs, but the increasing expansion and prominence of the public service.[1]

The continuous association of the building with government uses and the changes made to the building during the twentieth century, even in minor ways, have the ability to demonstrate important new conditions in the wider community such as increased employment opportunities for women.[14][1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The Chief Secretary's building is of aesthetic significance because its primary contribution to the surviving Victorian era streetscapes in Phillip Street, Macquarie Street and, in particular Bridge Street. It remains a dominant building in the pre-eminent administrative and political quarter of Sydney.[1]

The finishes and artworks purposely bought for the building, many from the Sydney International Exhibition and some commissioned in London, are of the highest quality and lavishness. They not only demonstrate the prestige of the department but are exemplars of late nineteenth century public taste and refinement.[1]

The Chief Secretary's building is of architectural significance because of the high quality of its architectural composition and execution, both externally and internally. It represents two works of great importance in the professionals careers of two outstanding nineteenth century architects. Barnet as Colonial Architect, considered it second only to his work at the GPO. The additions by Vernon represent one of the first and major works by the newly appointed Government Architect. That they were completed in a style and quality matching that of the original building (at least outwardly) in a time of severe economic recession is a further testament to the contemporary importance attached to this building. The Chief Secretary's Building remains one of the pre-eminent public buildings of the nineteenth century, comparing equally with the GPO and Sydney University.[15][1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The Chief Secretary's building has social significance because it was the workplace of departments including Public Works which, more than other, had overwhelming influence on all aspects of life at every level of society. The size and finish of the building and its various artworks demonstrate the importance and esteem afforded to the office necessary for the workings of government.[1]

The Executive Council Chamber derives significance from its lengthy association with the key decision-making apparatus of State government.[16][1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The building has scientific/technical significance by the use of corrugated aluminium roofing on the dome, one of the earliest uses of this cladding material in Australia.[15][1]

The building may have some archaeological potential to yield information about the use of the site as the Government Domain and the grounds of the first Government House. The fabric has the potential to demonstrate significant, but unrecorded aspects of past use and occupancy, e.g. The lift and the flag cupboard on level six.[1]

The building has the potential for the recovery of original decorative schemes, the recording restoration and reinstatement of which can inform and enhance the interpretation of the building and an understanding of Victorian public buildings generally.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The Chief Secretary's Building is a rare example of a 19th-century government office of this scale and quality. The building contains a unique collection of objects acquired from the 1879 International Exhibition, the choice of which was representative of the historical, artistic, and literary tastes of Sir Henry Parkes. The building contains a rare example of a highly significant, in-situ collection of artefacts that have been in continuous use. The choice of aluminium to cover dome in 1895-1896 is believed to have been the earliest such use of this metal in the world. It is a rare, though not unique, example of such offices on this scale.[1]

The building is also listed on the (now defunct) Register of the National Estate.[2]

Gallery

Macquarie Street entrance signed 'Colonial Secretary'. A statue of Queen Victoria is barely visible through the door.

Macquarie Street entrance signed 'Colonial Secretary'. A statue of Queen Victoria is barely visible through the door.- The stairwell and original wire cage lift shaft, still in use.

See also

References

- "Chief Secretary's Building". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00766. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Chief Secretarys Building, 121 Macquarie St, Sydney, NSW, Australia (Place ID 1824)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Australian Heritage Commission (1981). The Heritage of Australia: the illustrated register of the National Estate. South Melbourne: The Macmillan Company of Australia in association with the Australian Heritage Commission. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-333-33750-9.

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:26

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:34 & 51

- Government Architect's Office; Group GSA Pty Ltd (2003). "Chief Secretary's Building". architecture.com.au. The Royal Australian Institute of Architects. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Hutchison, Noel S. (1976). "Simonetti, Achille (1838–1900)" (Hardcopy). Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Search: Australian Constitutional Conventions of 1890s". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Heritage: Chief Secretary's Building". Government Architect's Office. Department of Public Works, Government of New South Wales. 2005. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Heritage: Chief Secretary's Building" (PDF). Government Architect's Office. Department of Public Works, Government of New South Wales. December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:33

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:37-39

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:65

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:62-63

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:64

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis 1994:63

Bibliography

- "Colony Walking Tour". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Colony Walking Tour" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

Attribution

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chief Secretary’s Building, Sydney. |