Cherubikon

The Cherubikon (Greek: χερουβικόν) (χερουβικὸς ὕμνος), Old Church Sl. {{script|Cyrs|Херувімскаѧ пҍснь}, Cherubic Hymn}), is the usual troparion sung at the Great Entrance during the Byzantine liturgy.

The hymn symbolically incorporates those present at the liturgy into the presence of the angels gathered around God's throne.[1] It concerns the very heart of the Divine Liturgy—the Anaphora, the earliest part which can be traced back to Saint Basil and to John Chrysostom's redaction of Basil's liturgical text.

History

Origin

The cherubikon was added as a troparion to the Divine Liturgy under Emperor Justin II (565 – 578) when a separation of the room where the gifts are prepared from the room where they are consecrated made it necessary that the Liturgy of the Faithful, from which those not baptised had been excluded, start with a procession.[2] This procession is known as the Great Entrance, because the celebrants have to enter the choir by the altar screen, later replaced by the iconostasis. The chant genre offertorium in traditions of Western plainchant was basically a copy of the Byzantine custom, but there it was a proper mass chant which changed regularly.

Although its liturgical concept already existed by the end of the 4th century, the cherubikon itself was created 200 years later. The Great Entrance as a ritual act is needed for a procession with the Gifts while simultaneous prayers and ritual acts are performed by the clergy. As the processional troparion, the cherubikon has to bridge the long way between prothesis, a room outside the apsis, and the sanctuary which had been separated by changes in sacred architecture under Emperor Justin II. The cherubikon is divided into several parts.[3] The first part is sung before the celebrant begins his prayers, there were one or two simultaneous parts, and they all followed like a gradual ascent in different steps within the Great Entrance. Verses 2-5 were sung by a soloist called monophonaris from the ambo. The conclusion with the last words of verse 5 and the allelouiarion are sung in dialogue with the domestikos and the monophonaris.

Liturgical use

Concerning the text of the processional troparion which was ascribed to Justin II, it is not entirely clear, whether "thrice-holy hymn" did refer to the Sanctus of the Anaphora or to another hymn of the 5th century known as the trisagion in Constantinople, but also in other liturgical traditions like the Latin Gallican and Milanese rites. Concerning the old custom of Constantinople, the trisagion was used as a troparion of the third antiphonon at the beginning of the divine liturgy as well as of hesperinos. In the West, there were liturgical customs in Spain and France, where the trisagion replaced the great doxology during the Holy Mass on lesser feasts.[4]

The troparion of the great entrance (at the beginning of the second part of the divine liturgy which excluded the catechumens) was also the prototype of the genre offertorium in Western plainchant, although its text only appears in the particular custom of the Missa graeca celebrated on Pentecost and during the patronal feast of the Royal Abbey of Saint Denis, after the latter's vita became associated with Pseudo-Dionysios Areopagites. According to the local bilingual custom the hymn was sung both in Greek and in Latin translation.

Today, the separation of the prothesis is part of the early history of the Constantinopolitan rite (akolouthia asmatike). With respect to the Constantinopolitan customs there are many different local customs in Orthodox communities all over the world and there are urban and monastic choir traditions in different languages into which the cherubikon has been translated.

Exegetic tradition of Isaiah

The trisagion or thrice-holy hymn which was mentioned by John Chrysostom, could only refer to the Sanctus of the Anaphora taken from the Old Testament, from the book of the prophet Isaiah in particular (6:1-3):

[1] Καὶ ἐγένετο τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ, οὗ ἀπέθανεν Ὀζίας ὁ βασιλεύς, εἶδον τὸν κύριον καθήμενον ἐπὶ θρόνου ὑψηλοῦ καὶ ἐπηρμένου, καὶ πλήρης ὁ οἶκος τῆς δόξης αὐτοῦ. [2] καὶ σεραφὶμ εἱστήκεισαν κύκλῳ αὐτοῦ, ἓξ πτέρυγες τῷ ἑνὶ καὶ ἓξ πτέρυγες τῷ ἑνί, καὶ ταῖς μὲν δυσὶν κατεκάλυπτον τὸ πρόσωπον καὶ ταῖς δυσὶν κατεκάλυπτον τοὺς πόδας καὶ ταῖς δυσὶν ἐπέταντο. [3] καὶ ἐκέκραγον ἕτερος πρὸς τὸν ἕτερον καὶ ἔλεγον Ἅγιος ἅγιος ἅγιος κύριος σαβαώθ, πλήρης πᾶσα ἡ γῆ τῆς δόξης αὐτοῦ.[5]

[1] And it came to pass in the year in which king Ozias died, that I saw the Lord sitting on a high and exalted throne, and the house was full of his glory. [2] And seraphs stood round about him, each one had six wings, and with two they covered their face, and with two they covered their feet, and with two they flew. [3] And one cried to the other, and they said "Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts! The whole earth is full of His glory!"

In a homily John Chrysostom interpreted Isaiah and the chant of the divine liturgy in general (neither the cherubikon nor the trisagion existed in his time) as an analogue act which connected the community with the eternal angelic choirs:

Ἄνω στρατιαὶ δοξολογοῦσιν ἀγγέλων· κᾶτω ἐν ἐκκλησίαις χοροστατοῦντες ἄνθρωποι τὴν αὐτὴν ἐκείνοις ἐκμιμοῦνται δοξολογίαν. Ἄνω τὰ Σεραφὶμ τὸν τρισάγιον ὕμνον ἀναβοᾷ· κάτω τὸν αὑτὸν ἠ τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἀναπέμπει πληθύς· κοινὴ τῶν ἐπουρανίων καὶ τῶν ἐπιγείων συγκροτεῖται πανήγυρις· μία εὐχαριστία, ἓν ἀγαλλίαμα, μία εὐφρόσυνος χοροστασία.[6]

On high, the armies of angels give glory; below, men, standing in church forming a choir, emulate the same doxologies. Above, the Seraphim declaim the thrice-holy hymn; below, the multitude of men sends up the same. A common festival of the heavenly and the earthly is celebrated together; one Eucharist, one exultation, one joyful choir.

The anti-cherubika

The cherubikon belongs to the ordinary mass chant of the divine liturgy ascribed to John Chrysostom, because it has to be sung during the year cycle, however, it is sometimes substituted by other troparia, the so-called "anti-cherubika", when other formularies of the divine liturgy are celebrated. On Holy Thursday, for example, the cherubikon was, and still is, replaced by the troparion "At your mystical supper" (Τοῦ δείπνου σου τοῦ μυστικοῦ) according to the liturgy of Saint Basil, while during the Liturgy of the Presanctified the troparion "Now the powers of the heavens" (Νῦν αἱ δυνάμεις τῶν οὐρανῶν) was sung, and the celebration of Prote Anastasis (Holy Saturday) uses the troparion from the Liturgy of St. James, "Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence" (Σιγησάτω πᾶσα σὰρξ βροτεία). The latter troparion is also used occasionally at the consecration of a church.[1]

Text

In the current traditions of Orthodox chant, its Greek text is not only sung in older translations such as the one in Old Church Slavonic or in Georgian, but also in Romanian and other modern languages.

In the Greek text, the introductory clauses are participial, and the first person plural becomes apparent only with the verb ἀποθώμεθα "let us lay aside". The Slavonic translation mirrors this closely, while most other translations introduce a finite verb in the first person plural already in the first line (Latin imitamur, Georgian vemsgavsebit, Romanian închipuim "we imitate, represent").

- Greek

- Οἱ τὰ χερουβὶμ μυστικῶς εἰκονίζοντες

- καὶ τῇ ζωοποιῷ τριάδι τὸν τρισάγιον ὕμνον προσᾴδοντες

- πᾶσαν τὴν βιωτικὴν ἀποθώμεθα μέριμναν

- Ὡς τὸν βασιλέα τῶν ὅλων ὑποδεξόμενοι

- ταῖς ἀγγελικαῖς ἀοράτως δορυφορούμενον τάξεσιν

- ἀλληλούϊα ἀλληλούϊα ἀλληλούϊα[7]

- 10th-century Latin transliteration of the Greek text

- I ta cherubim mysticos Iconizontes

- ke ti zopion triadi ton trisagyon ymnon prophagentes

- passa nin biotikin apothometa merinnan·

- Os ton basileon ton olon Ipodoxomeni

- tes angelikes aoraton doriforumenon taxasin

- alleluia.[8]

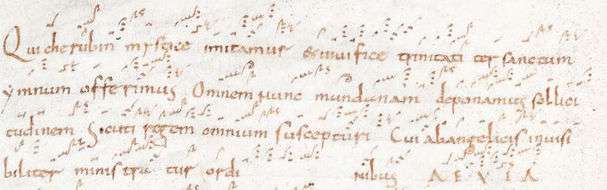

- Latin

- Qui cherubin mystice imitamur

- et vivifice trinitati ter sanctum ẏmnum offerimus

- Omnem nunc mundanam deponamus sollicitudinem

- Sicuti regem omnium suscepturi

- Cui ab angelicis invisibiliter ministratur ordinibus

- A[ll]E[l]UIA[9]

- English translation

- We who mystically represent the Cherubim,

- and who sing to the Life-Giving Trinity the thrice-holy hymn,

- let us now lay aside all earthly cares

- that we may receive the King of all,

- escorted invisibly by the angelic orders.

- Alleluia[10]

- Church Slavonic

- Иже херѹвимы тайнѡ ѡбразѹюще,

- и животворѧщей Троицѣ трисвѧтую пѣснь припѣвающе,

- Всѧкое нынѣ житейское отложимъ попеченіе.

- Ꙗкѡ да Царѧ всѣхъ подъимемъ,

- аггельскими невидимѡ дорѵносима чинми.

- Аллилѹіа[11]

- Transliterated Church Slavonic

- Íže heruvímy tájnō ōbrazujúšte,

- i životvoręštej Tróicě trisvętúju pěsňĭ pripěvájúšte,

- Vsęko[j]e nýňě žitéjsko[j]e otložimŭ popečenìe.

- Jákō da Carę vsěhŭ podŭimemŭ,

- ángelĭskimi nevídimō dorỳnosíma čínmi.

- Allilúia[12]

- Transliterated Georgian

- romelni qerubimta saidumlosa vemsgavsebit,

- da tskhovelsmq'opelisa samebisa, samgzis ts'midasa galobasa shenda shevts'iravt,

- q'ovelive ats' soplisa daut'eot zrunva.

- da vitartsa meupisa q'oveltasa,

- shemts'q'narebelsa angelostaebr ukhilavad, dzghvnis shemts'irvelta ts'estasa.

- aliluia, aliluia, aliluia

- Romanian

- Noi, care pe heruvimi cu taină închipuim,

- Şi făcătoarei de viaţă Treimi întreit-sfântă cântare aducem,

- Toată grija cea lumească să o lepădăm.[15]

- Ca pe Împăratul tuturor, să primim,

- Pe Cel înconjurat în chip nevăzut de cetele îngereşti.

- Aliluia, aliluia, aliluia.[16]

The notated chant sources

Due to the destruction of Byzantine music manuscripts, especially after 1204, when Western crusaders expelled the traditional cathedral rite from Constantinople, the chant of the cherubikon appears quite late in the musical notation of the monastic reformers, within liturgical manuscripts not before the late 12th century. This explains the paradox, why the earliest notated sources which have survived until now, are of Carolingian origin. They document the Latin reception of the cherubikon, where it is regarded as the earliest prototype of the mass chant genre offertorium, although there is no real procession of the gifts.

The Latin cherubikon of the "Missa greca"

The oldest source survived is a sacramentary ("Hadrianum") with the so-called "Missa greca" which was written at or for the liturgical use at a Stift of canonesses (Essen near Aachen).[17] The transliterated cherubikon in the center like the main parts of the Missa greca were notated with paleofrankish neumes between the text lines. Paleofrankish neumes are adiastematic and no manuscripts with the Latin cherubikon have survived in diastematic neumes. Nevertheless, it is supposed to be a melos of an E mode like the earliest Byzantine cherubika which have the main intonation of echos plagios deuteros.[18]

In this particular copy of the Hadrianum the "Missa greca" was obviously intended as proper mass chant for Pentecost, because the cherubikon was classified as offertorium and followed by the Greek Sanctus, the convention of the divine liturgy, and finally by the communio "Factus est repente", the proper chant of Pentecost. Other manuscripts belonged to the Abbey Saint-Denis, where the Missa greca was celebrated during Pentecost and in honour of the patron within the festal week (octave) dedicated to him.[19] Sacramentaries without musical notation transliterated the Greek text of the cherubikon into Latin characters, while the books of Saint-Denis with musical notation translated the text of the troparion into Latin. Only the Hadrianum of Essen or Korvey provided the Greek text with notation and served obviously to prepare cantors who did not know Greek very well.

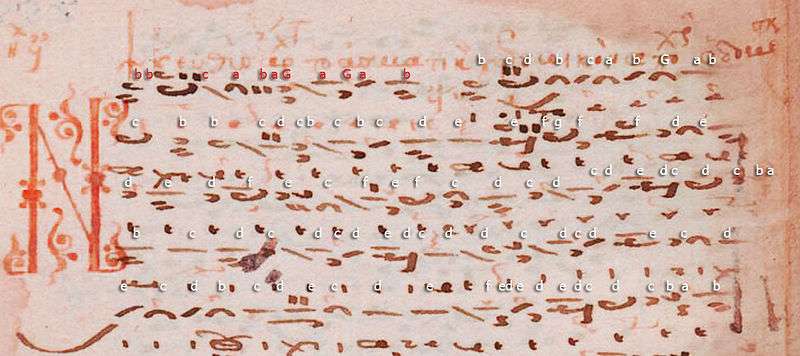

The cherubikon asmatikon

In the tradition of the cathedral rite of the Hagia Sophia, there was only one melody in the E mode (echos plagios devteros, echos devteros), which has survived in the Asmatika (choir books) and, in a complete form, as "cherouvikon asmatikon" in the books Akolouthiai of the 14th and 15th century.

Akolouthiai manuscript about 1400 (A-Wn Theol. gr. 185, f. 255v)

In this later elaboration, the domestikos, leader of the right choir, sings an intonation, and the right choir performs the beginning until μυστικῶς. Then the domestikos intervenes with a kalopismos over the last syllable το—το and a teretismos (τε—ρι—ρεμ). The choir concludes the kolon with the last word εἰκονίζοντες. The left choir is replaced by a soloist, called "Monophonaris" (μονοφωνάρις), presumably the lampadarios or leader of the left choir. He sings the rest of the text from an ambo. Then the allelouia (ἀλληλούϊα) is performed with a long final teretismos by the choir and the domestikos.[20]

The earlier asmatika of the 13th century only contain those parts sung by the choir and the domestikos. These asmatic versions of the cherubikon are not identical, but composed realizations, sometimes even the name of the cantor was indicated.[21] Only one manuscript, a 14th-century anthology of the asma, has survived in the collection of the Archimandritate Santissimo Salvatore of Messina (I-ME Cod. mess. gr. 161) with the part of the psaltikon. It provides a performance of the monophonaris together with acclamations or antiphona in honour of the Sicilian King Frederick II and can be dated back to his time.[22]

The cherubikon palatinon

Another shorter version, composed in the echos plagios devteros without any teretismoi, inserted sections with abstract syllables, was still performed during celebrations of the imperial court of Constantinople by the choir during the 14th century.[23] A longer elaboration of the cherubikon palatinon attributed to "John Koukouzeles" was transcribed and printed in the chant books used by protopsaltes today.[24]

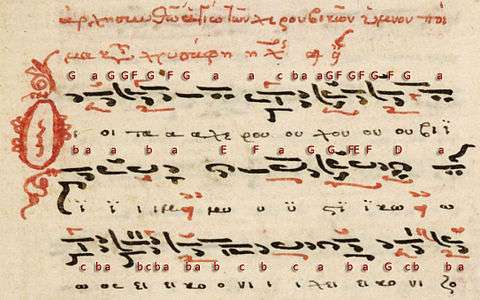

Papadic cherubikon cycles

Today the common practice is to perform the cherubikon according to the echos of the week (octoechos). One of the earliest sources with an octoechos cycle is an Akolouthiai manuscript by Manuel Chrysaphes (GR-AOi Ms. 1120) written in 1458. He had composed and written down an own cycle of 8 cherubika in the papadic melos of the octoechos.[25]

Until the present day the protopsaltes at the Patriarchate of Constantinople are expected to contribute their own realization of the papadic cycles.[26] Because the length of the cherubikon was originally adapted to the ritual procession, the transcriptions of the print editions according to the New Method distinct between three cycles. A short one for the week days (since the divine liturgy became a daily service), a longer one for Sundays, and an elaborated one for festival occasions, when a bishop or abbot joined the procession.

Notes

- Parry (1999), p. 117.

- Brightman (1896, p. 532, n. 9).

- For a detailed list of all simultaneous ritual acts and the particular celebration at the Hagia Sophia cathedral see Moran (1979, 175-177).

- See the evidence in a homiletic explanation of the Old Gallican Liturgy by Pseudo-Germanus (1998).

- Classical Septuagint translation of the Old Testament. "Isaiah 6". myriobiblos.gr (in Greek). Library of the Church of Greece.

- PG 56 (1862), col. 97.

- Brightman, ed. (1896, 377 & 379).

- Transliteration according to the Carolingian sacramentary of the 10th century (D-DÜl Ms. D2, f. 203v). About the particular orthography of the Latin transliteration and different medieval text versions of the Greek cherubikon (Wanek 2017, 97; Moran 1979, 172-173).

- Quoted after the source GB-Lbl Ms. Harley 3095, f. 111v.

- Raya (1958, p. 82).

- Херувимска пҍцнь отъ Иона Кукузеля (Sarafov 1912, 203-210). Examples of the Bulgarian tradition are the Cheruvimskaya Pesn sung by the Patriarch Neofit (monodic tradition) and the so-called "Bělgarskiy Razpev", closely related to Ukrainian and Russian traditions (Starosimonovskiy Rozpev, Obihodniy Rozpev, or several arrangements by more or less known composers of the 19th and 20th centuries etc.).

- The variant “je” (transcription for ѥ instead of е) is common for the early sources of the East Slavic territory (Kievan Rus').

- See the transcription of the cherubikon by the Chant Center of the Georgian Patriarchate sung according to the tradition of the Gelati monastery: "Georgian cherubikon (school of Gelati Monastery)". Ensemble Shavnabada. According to the school of Vasili and Polievktos Karbelashvili (John Graham about the transcription movement): "First part of the cherubikon (Karbelashvili school)". Anchiskhati Church Choir. A third version with a female Ensemble: "Georgian cherubikon in sada kilo ("plane manner") in the traditional sixth mode (plagios devteros)".

- Second part of the cherubikon sung according to the tradition of the Gelati monastery: "Second part of the Georgian cherubikon (school of Gelati Monastery)". Anchiskhati Church Choir. Another tradition: "Second part of the Georgian cherubikon (school of Karbelashvili)". Anchiskhati Church Choir.

- "Heruvicul (glas I)". Mănăstirea Cămârzani.

- "Ca per Împăratul (glas I)". Cathedral of the Patriarchate Bucharest: Gabriel Bogdan.

- D-DÜl Ms. D2, f. 203v. "Hadrianum" is called the sacramentary which was sent by Pope Adrian I, after Charlemagne asked for the one of Gregory the Great.

- The cherubikon according to the version of manuscript British Library Ms. Harley 3095 has been reconstructed by Oliver Gerlach (2009, pp. 432-434). A reconstruction of the melody in Ms. D2 (D-DÜl) was done by Marcel Pérès in collaboration with the Orthodox protopsaltes Lycourgos Angelopoulos.

- Michel Huglo (1966) described the different sources of the cherubikon with musical notation, a Greek mass was held for Saint Denis at the abbey of Paris, the Carolingian mausoleum. Since the patron became identified with the church father Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in the time of Abbot Hilduin, when Byzantine legacies had been received to improve the diplomatic relationship between Louis the Pious and Michael II, a Greek mass was held to honour the patron. The services were supposed to be celebrated in Greek and Latin, see the Ordo officii of Saint-Denis (F-Pn lat. 976, f. 137) and the Greek Lectionary (F-Pn gr. 375, ff. 153r-154r, 194v).

- Konstantinos Terzopoulos (2009) confronted the editions which Konstantinos Byzantios (ca. 1777–1862) and Neofit Rilski both published of the typikon of Constantinople, with sources of the mixed rite during the Palaiologan dynasty. One of the manuscripts he used to illustrate is an Akolouthiai of the 15th century with the cherubikon asmatikon (GR-An Ms. 2406).

- See the transcriptions by Neil Moran (1975).

- Moran (1979).

- GR-An Ms. 2458, ff. 165v-166r [nearly one page] (Akolouthiai written in 1336).

- A Greek (Kyriazides 1896, pp. 278-287) and a Bulgarian Anthology (Sarafov 1912, pp. 203-210).

- Cappela Romana (1 February 2013) under direction of Alexander Lingas sings Manuel Chrysaphes' echos protos version with its teretismoi based on a transcription of Iveron 1120 by Ioannis Arvanitis and in the simulated acoustic environment of the Hagia Sophia.

- Listen to Thrasyvoulos Stanitsas (1961) who sings his own version of the cherubikon for the echos plagios protos. A huge collection of realisations from different periods had been published by Neoklis Levkopoulos at Psaltologion (2010).

References

Sources

- "Düsseldorf, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Ms. D2". Sacramentary written in Korvey (late 10th century).

- Ruotbert. "London, British Library, Ms. Harley 3095". Glossed anthology dedicated to the death of Boethius and his "De consolatione philosophiae" and a sequentiary, probably written in Cologne (late 10th century), one folio was added after the first part with a resurrection mass, using the symbolum Athanasium and the Latin cherubikon (early 11th century).

- "Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fonds grec, ms. 375". Greek Missal-Lectionary (Pentecostarion with the Divine Liturgy for Easter and stichera heothina, Menaion) of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis (1022).

- "Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fonds latin, ms. 976, f. 137". Missa greca in the Order of services (Ordo officii) of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis (about 1300).

- Koukouzeles, Ioannes; Korones, Xenos; Kladas, Ioannes (1400). "Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. theol. gr. 185". Βιβλίον σὺν Θεῷ ἁγίῳ περιέχον τὴν ἄπασαν ἀκολουθίαν τῆς ἐκκλησιαστικῆς τάξεως συνταχθὲν παρὰ τοῦ μαΐστορος κυροῦ Ἰωάννου τοῦ Κουκουζέλη. Thessaloniki.

- Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes. "London, British Library, Harley Ms. 5544". Papadike and the Anastasimatarion of Chrysaphes the New, and an incomplete Anthology for the Divine Liturgies (17th century). British Library. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

Editions

- Brightman, Frank Edward (1896). Liturgies, Eastern and Western, being the texts original or translated of the principal liturgies of the church. 1: Eastern Liturgies. Oxford: Clarendon.

- John Chrysostom (1862). Migne, Jacques-Paul (ed.). "Ἔπαινος τῶν ἀπαντησάντων ἐν τῇ ἐκκλησίᾳ, καὶ περὶ εὐταξίας ἐν ταῖς δοξολογίαις. Καὶ εἰς τὸ, "Εἶδον τὸν Κύριον καθήμενον ἐπὶ θρόνου ὑψηλοῦ καὶ ἐπηρμένου [Homilia in laudem eorum, qui comparuerunt in ecclesia, quaeque moderatio sit servanda in divinibus laudibus. Item in illud, vidi dominum sedentem in solio excelso (a) (Isai. 6,1)]". Patrologia Graeco-latina. 56: col. 97–107.

- Kyriazides, Agathangelos (1896). Ἓν ἄνθος τῆς καθ' ἡμᾶς ἐκκλησιαστικῆς μουσικῆς περιέχον τὴν ἀκολουθίαν τοῦ Ἐσπερινοῦ, τοῦ Ὅρθρου καὶ τῆς Λειτουργίας μετὰ καλλοφωνικῶν Εἱρμῶν μελοποιηθὲν παρὰ διαφόρων ἀρχαίων καὶ νεωτέρων Μουσικοδιδασκάλων. Istanbul: Alexandros Nomismatides.

- Levkopoulos, Neoklis, ed. (2010). "Cherouvikarion of Psaltologion". Thessaloniki. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Pseudo-Germain (1998). "Expositio Antiquae Liturgiae Gallicanae". In James W. McKinnon; William Oliver Strunk; Leo Treitler (eds.). The Early Christian Period and the Latin Middle Ages. Source readings in music history. 1 (Rev. ed.). New York: Norton. pp. 164–171. ISBN 0393966941.

- Raya, Joseph (1958). Byzantine Liturgy. Tournai, Belgium: Societe Saint Jean l'Evangelist, Desclee & Cie.

- Sarafov, Petĕr V. (1912). Рѫководство за практическото и теоретическо изучване на восточната църковна музика ["Manual for the practical and theoretical study of the oriental church music", includes an Anthology of Ioan Kukuzel's compositions, Doxastika of the Miney by Iakovos and Konstantinos the Protopsaltes, a Voskresnik, and Anthologies for Utrenna and the Divine Liturgies]. Sofia: Peter Gluškov.

- Soroka, Rev. L. (1999). Orthodox Prayer Book. South Canaan, Pennsylvania 18459 U.S.A.: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press. ISBN 1-878997-34-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

Studies

- Gerlach, Oliver (2009). Im Labyrinth des Oktōīchos – Über die Rekonstruktion mittelalterlicher Improvisationspraktiken in liturgischer Musik. 2. Berlin: Ison. ISBN 978-3-00-032306-5.

- Huglo, Michel (1966). Westrup, Jacques (ed.). "Les chants de la Missa greca de Saint-Denis". Essays Presented to Egon Wellesz. Oxford: Clarendon: 74–83.

- Moran, Neil K. (1975). The Ordinary chants of the Byzantine Mass. Hamburger Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft. 2. Hamburg: Verlag der Musikalienhandlung K. D. Wagner. pp. 86–140. ISBN 978-3-921029-26-8.

- Moran, Neil K. (1979). "The Musical 'Gestaltung' of the Great Entrance Ceremony in the 12th century in accordance with the Rite of Hagia Sophia". Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik. 28: 167–193.

- Parry, Ken; David Melling, eds. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA.: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23203-6.

- Terzopoulos, Konstantinos (2009). Patriarchal Chant Rubrics from Konstantinos Byzantios' Notebook for the Typikon: 1806–1828. 2nd International Conference of the American Society of Byzantine Music and Hymnography (ASBMH-2009). Presentation (move the cursor on the left side to navigate between the slides).

- Wanek, Nina-Maria (2017). "The Greek and Latin Cherubikon". Plainsong and Medieval Music. 26 (2): 95–114. doi:10.1017/S0961137117000043.

External links

Georgian Chant

- Graham, John A. "Georgian Chant History—Transcription Movement". Georgian Chant.

- "CD to learn Georgian Chant of the Divine Liturgies (school of Gelati Monastery)". Shavnabada Net. Tbilisi: Ensemble Shavnabada.

- "Anchiskhati Choir". Tbilisi.

Old Slavonic Cherubim Chant

- "Cheruvimskaya Pesn (1st Glas) in Demestvenny Rozpev (17th century) sung by the Chronos Ensemble".

- "Cheruvimskaya Pesn (5th Glas) sung by Neofit, Metropolit of Russe".

- "Cheruvimskaya Pesn (1st Glas) in Old Bulgarian Razpev". St Petersburg: "Optina Pustyn" Male Choir.

- "Cheruvimskaya Pesn in Obihodniy Rozpev". Regenta Church Choir.

- "Cheruvimskaya Pesn in Starosimonovskiy Rozpev". Minsk: Choir of the St Elisabeth Monastery.

- L'vovsky, Grigory F. "Cheruvimskaya Pesn". Female Ensemble of the Regenta Church Choir.

- Kastalsky, Alexander Dimitriyevich. "Cheruvimskaya Pesn". Saratov: Holy Trinity Choir.

Papadic Cherubika

- Manuel Chrysaphes; Ioannis Arvanitis (2013). "Cherouvikon echos protos with teretismos". Cappella Romana.

- Phokaeos, Theodoros. "Cherouvikon syntomon (short version) echos varys sung by Dionysios Firfires".

- Stanitsas, Thrasyvoulos (1961). "Cherouvikon echos plagios protos sung by the composer".