Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe

Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States holding that an Indian tribe has the authority to impose taxes on non-Indians that are conducting business on the reservation as an inherent power under their tribal sovereignty.[1][2]

| Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 30, 1981 Reargued November 4, 1981 Decided January 25, 1982 | |

| Full case name | Merrion et al., DBA Merrion & Bayless, et al. v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe et al. |

| Citations | 455 U.S. 130 (more) 102 S. Ct. 894; 71 L. Ed. 2d 21; 1982 U.S. LEXIS 25; 72 Oil & Gas Rep. 617 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 617 F.2d 537 (10th Cir. 1980). ; Merrion and Bayless, et al. v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, et al., No. 77-292P and No. 77-343P, (D. N.Mex., 1979) (not reported) |

| Holding | |

| Held that an Indian tribe has the authority to impose taxes on non-Indians that are conducting business on the reservation as an inherent power under their tribal sovereignty. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Marshall, joined by Brennan, White, Blackmun, Powell, O'Connor |

| Dissent | Stevens, joined by Burger, Rehnquist |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art I, §8; 25 U.S.C. § 398a, et seq. | |

Background

History

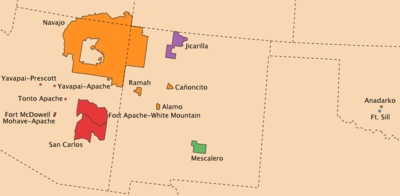

The Jicarilla Apache Tribe is a Native American (Indian) tribe in northwestern New Mexico on a reservation of 742,315 acres (3,004.04 km2; 1,159.867 sq mi). The reservation was established by an Executive Order of President Grover Cleveland in 1887[3] and clarified by the Executive Orders of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 and William Howard Taft in 1912. The tribe adopted a formal constitution under the provisions of the Indian Reorganization Act, 25 U.S.C. § 461 et seq. that provided for the taxation of members of the tribe and non-members of the tribe doing business on the reservation. If the tribe enacted a such tax ordinance on non-members, the ordinance had to be approved by the Secretary of the Interior.[1]

Beginning in 1953, the tribe entered into agreements with oil companies, including the plaintiffs Merrion and Bayless, to provide oil and gas leases. The leases were approved by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (now the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA) in accordance with 25 U.S.C. §§ 396a–396g. As was the usual practice at the time, the oil companies negotiated directly with BIA, who then presented the contracts to the tribal council.[4] While the oil and gas was from reservation land, Merrion paid severance taxes to the state of New Mexico under the provisions of 25 U.S.C. § 398c, where Congress had authorized such taxation in 1927. The leases provided for royalties to be paid to the tribe, but the BIA was lax in collecting them. In 1973, tribal attorneys wrote to the BIA to demand the collection of royalties, and after a year delay, the BIA would only state that they were "looking into it."[2] In 1976, the BIA approved a tribal ordinance that also provided for a severance tax.[1] This tax was set at 29 cents (U.S.) per barrel of oil and at 5 cents per million British thermal units (BTU) for natural gas.[2]

District court

Merrion did not want to pay a severance tax to both New Mexico and the tribe, and filed suit in the United States District Court for the District of New Mexico, along with such major companies as Atlantic Richfield (now part of BP), Getty Oil, Gulf Oil, and Phillips Petroleum (now ConocoPhillips), among others. The case was not filed until 15 days before the severance tax was due.[2] In the hearing on the temporary injunction on June 17, 1977, Merrion argued that the tribe's severance tax was unconstitutional, violating both the Commerce clause and Equal protection clause, and that it was both taxation without representation and double taxation.[2] In addition, the plaintiffs argued against the entire concept of tribal sovereignty, stating that it had been a "legal fiction for decades."[2] U.S. District Judge H. Vearle Payne granted the temporary injunction and set the hearing on the permanent injunction for August 29, 1977. The oil companies showed up with approximately 40-50 attorneys, compared to 2 or 3 lawyers for the tribe.[2] Both sides made essentially the same arguments as for the temporary injunction. Following the hearing, District court ruled that the tribe's tax violated the Commerce clause of the Constitution and that only state and local authorities had the ability to tax mineral rights on Indian reservations. The court then issued a permanent injunction prohibiting the collection of the tax by the tribe.[1]

Circuit court

The case then went to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. The western states of Utah, New Mexico, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming filed amici curiae briefs in support of the oil companies, while the Navajo Nation, the Arapahoe Nation, the Shoshone Indian Tribe, the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation, and the National Congress of American Indians all filed briefs in support of the Jacrilla tribe.[2] The case was heard on May 29, 1979 by a three-judge panel consisting of Chief Judge Oliver Seth and Circuit Judges William Holloway, Jr. and Monroe G. McKay. The arguments were the same as at the district court level, with the oil companies stating that tribal sovereignty did not apply to taxation of non-Indians conducting business on the reservation. In an unusual move, no written decision was issued, and the attorneys were told to reargue the case en banc. McKay stated that as he recalls, he and Holloway were in disagreement with Seth, who favored a limited view of the tribe's authority to tax the oil companies.[2]

On September 12, 1979, the case was reheard before the entire panel. Following that hearing, in a 5-2 decision, the Tenth Circuit reversed the District Court, holding that the tribe had the inherent power under their tribal sovereignty to impose taxes on the reservation. The court also held that the tax did not violate the Commerce Clause nor place an undue burden on the oil companies.[1][2][5]

Opinion of the Court

Initial arguments

The oil companies immediately appealed and the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari to hear the case.[1] This appeal came shortly after the Supreme Court had decided Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978), which had stated that an Indian tribe did not have the authority to try a non-Indian for a crime committed on the reservation.[6] The Oliphant case was a major blow against tribal sovereignty, and was a case used by the oil companies in their briefs.[2] The oil companies argued that Oliphant, currently limited to criminal cases, should be expanded to civil matters as well. The attorneys for the tribe argued that this case was no different than Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation, 447 U.S. 134 (1980), which stated that tribes had the authority to impose a cigarette tax on both tribal members and non-Indians alike.[7] Amici briefs were filed by Montana, North Dakota, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Washington (state), the Mountain States Legal Foundation, the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, Shell Oil, and Westmoreland Resources in support of the oil companies. The Council of Energy Resource Tribes and the Navajo Nation filed briefs supporting the tribe.[1]

Arguing for Mellion and Bayless was Jason W. Kellahin, for Amoco and Marathon Oil was John R. Cooney (originally a separate case, but which was consolidated with this case), for the tribe was Robert J. Nordhaus, and on behalf of the tribe for the Solicitor General was Louis F. Claiborne. Kellahin argued that tribal sovereignty only extended to members of the tribe, citing both Oliphant and Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981),[8] both cases involving the jurisdiction of a tribal court over non-Indians. Kellahin stated that those cases that allowed a tribe to tax non-Indians were not due to tribal sovereignty, but were connected with the authority of the tribe to regulate who could enter the reservation, in the same manner as a landlord controlled their property. Cooney argued that the tax was a violation of the Commerce Clause, in that Congress divested the tribes of that authority when they enacted 25 U.S.C. § 398c granting the states the right to impose a severance tax on reservation lands. Nordhaus, in arguing for the tribe, pointed out that there was first, no Congressional preemption of the tribal authority to tax, and that second, taxation was an inherent power of tribal sovereignty. Claiborne first distinguished Montana, noting that it dealt with non-Indians on fee land owned by non-Indians that happened to be within the boundaries of the reservation, something that was completely unrelated to the current case.[2][9]

Re-argument

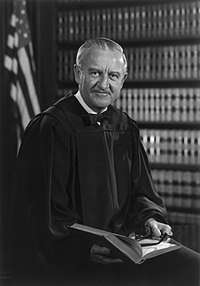

Following the oral argument, the Chief Justice assigned Justice John Paul Stevens to write the majority opinion and Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. asked Justice Thurgood Marshall to write the minority or dissenting opinion, based on the initial count of the justices' views. Since Justice Potter Stewart did not participate in the case, it would take a 5-3 vote to overturn the decision of the Circuit Court. Stevens circulated a memorandum stating that his decision would be to invalidate the tax - Chief Justice Warren Burger and Justice William Rehnquist immediately stated they would join his opinion. Justice Byron White stated that he would wait and see what the dissent said, and then indicated he would join the dissent in part. It also appeared that Justice Harry Blackmun was also going to write a separate dissent, but he also stated that he would wait to see Marshall's opinion. At this point, the tribe had the votes to win on a 4-4 vote, but the Court was close to being adjourned for the summer recess. On July 3, 1981, the Court notified the parties to reargue the case on November 4, 1981.[2]

In the meantime, the Court had changed. Justice Stewart retired, and President Ronald Reagan had appointed Sandra Day O'Connor to replace him. During the re-argument, Kellahin began with the fact the New Mexico was acquired via the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo and that neither Spain or Mexico recognized Indian title and claimed that the tax was a veiled attempt to increase royalty payments. Cooney argued that there was no authority in statute for the Secretary of the Interior to approve a tribal tax and that the 1927 statute preempted the tribes authority in favor of the states being empowered to apply a severance tax on reservations. Nordhaus stated that the argument about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo did not apply, since no branch of the federal government had ever differentiated between these tribes and other tribes. The case was then submitted to the court.[2][10]

Majority opinion

Justice Thurgood Marshall delivered the opinion of the court. Marshall noted that the tribe had a properly formed constitution, approved by the Secretary of the Interior, and that it included that the tribal council may impose taxes on non-members doing business on the reservation. He noted that the tribe had executed oil and gas leases for about 69% of the reservation and that the leases provided for royalties to be paid to the tribe. Marshall further noted that the tribe followed the proper process to enact a severance tax, obtaining the approval of the BIA as part of the process. The first argument of the oil companies that the power to tax only arose from the power of the tribe to exclude persons from the reservation. Marshall disagreed, stating that the power to tax is an inherent attribute of a tribe's sovereignty. Tribal government includes the need to provide for services, not only to the tribe, but to anyone doing business on the reservation. He noted that the oil companies benefited from police protection and other governmental services. Citing Colville, he stated that the tribe's interest in raising "revenues for essential governmental programs . . . is strongest when the revenues are derived from value generated on the reservation by activities involving the Tribes and when the taxpayer is the recipient of tribal services."[7] Marshall noted that Congress was able to remove this power, but had not done so, and had acknowledged in 1879 the power of the Cherokee Nation to tax non-Indians.[1]

Marshall further noted the oil companies' arguments that a lease would prevent a governmental body from later imposing a tax would denigrate tribal sovereignty, and that tribal sovereignty was not limited by contractual arrangements. Only the Federal government has the authority to limit the powers of a tribal government, and a non-Indian's consent is not needed (by contract or otherwise) to exercise its sovereignty, to the contrary, the tribe may set conditions and limits on the non-Indian as a matter of right. "To presume that a sovereign forever waives the right to exercise one of its sovereign powers unless it expressly reserves the right to exercise that power in a commercial agreement turns the concept of sovereignty on its head."[1]

Marshall then addressed the Commerce Clause issues, and the argument of the Solicitor General that the section of the Commerce Clause that dealt directly with Indians applied rather than the argument of the oil companies that the section dealing with interstate commerce applied. First, Marshall noted that the case history of the Indian Commerce Clause was to protect the tribes from state infringement, not to approve of Indian trade without constitutional restraint. He saw of no reason to begin now, especially since he did not find that the tribe's severance tax did not have negative implications on interstate commerce. In a 6-3 decision, Marshall found that the tribe had the right to impose such a tax on non-Indians.[1]

Dissent

Justice John Paul Stevens, joined by Chief Justice Burger and Justice Rehnquist, dissented from the majority opinion. Stevens noted that over its own members, a tribe has virtually unlimited sovereignty. Over non-Indians, a tribe had no power, but many tribes were granted the authority to exclude non-Indians from their reservations. Stevens also noted that the various statutes that were passed in regards to mineral rights and leases were silent as to the authority of a tribe to impose taxes. Therefore, authority must come from one of three sources, federal statutes, treaties, and inherent tribal sovereignty. He noted that in matters involving their own members, the tribe could act in manners that the federal government could not, such as discriminating against females in citizenship cases (citing Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978)).[11] Tribal authority over non-members was always severely limited, in both a civil and criminal context, and he viewed both Oliphant and Montana as controlling in this area also. He viewed the authority to tax as merely an adjunct to the tribe's right to exclude individuals from the reservation. Since the leases were entered into by the tribe voluntarily, the tribe cannot enact later taxes without the consent of the oil companies. Stevens would have reversed the Circuit Court.[1]

Subsequent developments

Almost immediately after the decision, the BIA, on directions from Assistant Secretary of the Interior Kenneth Smith, proposed federal regulations that would have severely limited the ability of the tribes to impose severance taxes. Following numerous complaints from the tribes, the BIA abandoned that plan.[2] The Jicarilla tribe has also purchased the Palmer Oil Company, becoming the first Indian tribe to have 100% ownership of an oil production firm.[2] The case is a landmark case in Native American case law,[12] having been cited in approximately 400 law review articles as of July 2010.[13][14] Almost all tribes that have mineral deposits now impose a severance tax, based on the Merrion decision[15] and has been used as the basis for subsequent decisions supporting tribal taxing authority.[16] Numerous books also mention the case, whether in regards to tribal sovereignty[17][18][19] or taxation.[17][20]

References

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982).

- Nordhaus, Robert, Hall, G. Emlen and Rudio, Anne Alise (2003), Revisiting Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe: Robert Nordhaus and Sovereign Indian Control over Natural Resources on Reservations, 43 Nat. Resources J. 223

- Roberts, Calvin A. (2005). Our New Mexico: A Twentieth Century History. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-8263-4008-5.

- Wilkinson, Charles F. (2005). Blood struggle: the rise of modern Indian nations. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 122, 248–251. ISBN 978-0-393-05149-0.

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 617 F.2d 537 (10th Cir. 1980).

- Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978)

- Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation, 447 U.S. 134 (1980)

- Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981)

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe - Oral Argument (MP3 and text) (Oral Argument). Washington, DC: The Oyez Project. March 30, 1981. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe - Oral Reargument (MP3 and text) (Oral Argument). Washington, DC: The Oyez Project. November 4, 1981. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978)

- National Indian Law Library, ed. (2002). Landmark Indian law cases. Boulder, CO: Wm. S. Hein Publishing. pp. 419–456. ISBN 978-0-8377-0157-8.

- Bowen, Veronica L. (1994), The Extent of Indian Regulatory Authority over Non-Indians:South Dakota v. Bourland, 27 Creighton L. Rev. 605

- Laurence, Robert (1984), Thurgood Marshall's Indian Law Opinions, 27 How. L.J. 3

- Royster, Judith V. (1994), Mineral Development in Indian Country: The Evolution of Tribal Control over Mineral Resources, 29 Tulsa L.J. 541

- Suanders, Stella (1997), Tax Law-Tribal Taxation and Allotted Lands: Mustang Production Company v. Harrison, 27 N.M.L. Rev. 455

- Wilkinson, Charles F. (1988). American Indians, time, and the law: native societies in a modern constitutional democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 39–45. ISBN 978-0-300-04136-1.

- Duthu, N. Bruce (2008). American Indians and the law. New York, NY: Penguin Group. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-670-01857-4.

- Lopach, James J.; Brown, Margery Hunter; Clow, Richmond L. (1998). Tribal government today: politics on Montana Indian reservations. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-87081-477-8.

- Nettheim, Garth; Craig, Donna; Meyers, Gary D. (2002). Indigenous peoples and governance structures: a comparative analysis of land and resource management rights. Canberra, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-85575-379-5.

External links

- Text of Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982) is available from: CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe - Oral Argument (MP3 and text) (Oral Argument). Washington, DC: The Oyez Project. March 30, 1981. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe - Oral Reargument (MP3 and text) (Oral Argument). Washington, DC: The Oyez Project. November 4, 1981. Retrieved August 2, 2010.