Chemosynthesis

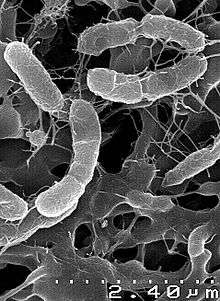

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrogen sulfide) or ferrous ions as a source of energy, rather than sunlight, as in photosynthesis. Chemoautotrophs, organisms that obtain carbon from carbon dioxide through chemosynthesis, are phylogenetically diverse, but also groups that include conspicuous or biogeochemically-important taxa include the sulfur-oxidizing gamma and epsilon proteobacteria, the Aquificae, the methanogenic archaea and the neutrophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria.

Many microorganisms in dark regions of the oceans use chemosynthesis to produce biomass from single carbon molecules. Two categories can be distinguished. In the rare sites where hydrogen molecules (H2) are available, the energy available from the reaction between CO2 and H2 (leading to production of methane, CH4) can be large enough to drive the production of biomass. Alternatively, in most oceanic environments, energy for chemosynthesis derives from reactions in which substances such as hydrogen sulfide or ammonia are oxidized. This may occur with or without the presence of oxygen.

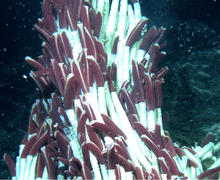

Many chemosynthetic microorganisms are consumed by other organisms in the ocean, and symbiotic associations between chemosynthesizers and respiring heterotrophs are quite common. Large populations of animals can be supported by chemosynthetic secondary production at hydrothermal vents, methane clathrates, cold seeps, whale falls, and isolated cave water.

It has been hypothesized that anaerobic chemosynthesis may support life below the surface of Mars, Jupiter's moon Europa, and other planets.[1] Chemosynthesis may have also been the first type of metabolism that evolved on Earth, leading the way for cellular respiration and photosynthesis to develop later.

Hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis process

Giant tube worms use bacteria in their trophosome to fix carbon dioxide (using hydrogen sulfide as an electron and oxygen[2] or nitrate as an energy source) and produce sugars and amino acids.[3] Some reactions produce sulfur:

- hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis:[4]

- 18H2S + 6CO2 + 3O2 → C6H12O6 (carbohydrate) + 12H2O + 18S

Instead of releasing oxygen gas while fixing carbon dioxide as in photosynthesis, hydrogen sulfide chemosynthesis produces solid globules of sulfur in the process. In bacteria capable of chemoautotrophy (a form a chemosynthesis), such as purple sulfur bacteria[5], yellow globules of sulfur are present and visible in the cytoplasm.

Discovery

In 1890, Sergei Winogradsky proposed a novel type of life process called "anorgoxydant". His discovery suggested that some microbes could live solely on inorganic matter and emerged during his physiological research in the 1880s in Strasbourg and Zürich on sulfur, iron, and nitrogen bacteria.

In 1897, Wilhelm Pfeffer coined the term "chemosynthesis" for the energy production by oxidation of inorganic substances, in association with autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation—what would be named today as chemolithoautotrophy. Later, the term would be expanded to include also chemoorganoautotrophs, which are organisms that use organic energy substrates in order to assimilate carbon dioxide.[6] Thus, chemosynthesis can be seen as a synonym of chemoautotrophy.

The term "chemotrophy", less restrictive, would be introduced in the 1940s by André Lwoff for the production of energy by the oxidation of electron donors, organic or not, associated with auto- or heterotrophy.[7][8]

Hydrothermal vents

The suggestion of Winogradsky was confirmed nearly 90 years later, when hydrothermal ocean vents were predicted to exist in the 1970s. The hot springs and strange creatures were discovered by Alvin, the world's first deep-sea submersible, in 1977 at the Galapagos Rift. At about the same time, then-graduate student Colleen Cavanaugh proposed chemosynthetic bacteria that oxidize sulfides or elemental sulfur as a mechanism by which tube worms could survive near hydrothermal vents. Cavanaugh later managed to confirm that this was indeed the method by which the worms could thrive, and is generally credited with the discovery of chemosynthesis.[9]

A 2004 television series hosted by Bill Nye named chemosynthesis as one of the 100 greatest scientific discoveries of all time.[10][11]

Oceanic crust

In 2013, researchers reported their discovery of bacteria living in the rock of the oceanic crust below the thick layers of sediment, and apart from the hydrothermal vents that form along the edges of the tectonic plates. Preliminary findings are that these bacteria subsist on the hydrogen produced by chemical reduction of olivine by seawater circulating in the small veins that permeate the basalt that comprises oceanic crust. The bacteria synthesize methane by combining hydrogen and carbon dioxide.[12]

References

- Julian Chela-Flores (2000): "Terrestrial microbes as candidates for survival on Mars and Europa", in: Seckbach, Joseph (ed.) Journey to Diverse Microbial Worlds: Adaptation to Exotic Environments, Springer, pp. 387–398. ISBN 0-7923-6020-6

- Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2020). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics” ACS Omega 5: 2221-2233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03352

- Biotechnology for Environmental Management and Resource Recovery. Springer. 2013. p. 179. ISBN 978-81-322-0876-1.

- "Chemolithotrophy | Boundless Microbiology". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- The Purple Phototrophic Bacteria. Hunter, C. Neil. Dordrecht: Springer. 2009. ISBN 978-1-4020-8814-8. OCLC 304494953.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kellerman, M. Y.; et al. (2012). "Autotrophy as a predominant mode of carbon fixation in anaerobic methane-oxidizing microbial communities". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (47): 19321–19326. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208795109.

- Kelly, D. P.; Wood, A. P. (2006). "The Chemolithotrophic Prokaryotes". The Prokaryotes. New York: Springer. pp. 441–456. doi:10.1007/0-387-30742-7_15.

- Schlegel, H. G. (1975). "Mechanisms of Chemo-Autotrophy" (PDF). In Kinne, O. (ed.). Marine Ecology. Vol. 2, Part I. pp. 9–60. ISBN 0-471-48004-5.

- Cavenaugh, Colleen M.; et al. (1981). "Prokaryotic Cells in the Hydrothermal Vent Tube Worms Rifttia Jones: Possible Chemoautotrophic Symbionts". Science. 213 (4505): 340–342. doi:10.1126/science.213.4505.340.

- "100 Greatest Discoveries (2004–2005)". IMDb.

- "Greatest Discoveries". Science. Archived from the original on March 19, 2013. Watch the "Greatest Discoveries in Evolution" online.

- "Life deep within oceanic crust sustained by energy from interior of Earth". ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 16, 2013.