Sergei Winogradsky

Sergei Nikolaievich Winogradsky ForMemRS[1] (or Vinogradskiy; Ukrainian: Сергій Миколайович Виноградський; 1 September 1856 – 25 February 1953) was a Russian microbiologist, ecologist and soil scientist who pioneered the cycle-of-life concept.[2][3]

Sergei Winogradsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 September 1856 |

| Died | 25 February 1953 (aged 96) Brie-Comte-Robert, France |

| Nationality | Russian empire |

| Citizenship | Russian and French |

| Alma mater | University of Saint Petersburg |

| Known for | Nitrogen cycle Chemoautotrophy Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria |

| Awards | Leeuwenhoek Medal (1935) Fellow of the Royal Society[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microbiology |

| Institutions | Imperial Conservatoire of Music in St Petersburg (piano) University of Saint Petersburg University of Strasbourg Pasteur Institute |

| Influences | Anton de Bary Nikolai Menshutkin (chemistry) Nevskia Famintzin (botany) Martinus Beijerinck |

| Influenced | Selman Waksman Martinus Beijerinck Vasily Leonidovitch Omelianski |

Winogradsky discovered the first known form of lithotrophy during his research with Beggiatoa in 1887. He reported that Beggiatoa oxidized hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as an energy source and formed intracellular sulfur droplets.[4] This research provided the first example of lithotrophy, but not autotrophy.

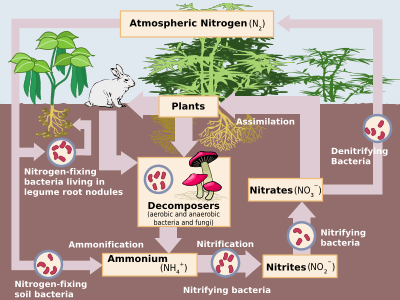

His research on nitrifying bacteria would report the first known form of chemoautotrophy, showing how a lithotroph fixes carbon dioxide (CO2) to make organic compounds.[5]

Biography

Winogradsky was born in Kiev (then in the Russian Empire). In this early stage of his life, Winogradsky was "strictly devoted to the orthodox faith", though he later became irreligious.[6]

He entered the Imperial Conservatoire of Music in St Petersburg in 1875 to study piano.[1] However, after two years of music training, he entered the University of Saint Petersburg in 1877 to study chemistry under Nikolai Menshutkin and botany under Andrei Sergeevich Famintzin.[1]

He received a diploma in 1881 and stayed at the St. Petersburg University for a degree of master of science in botany in 1884. In 1885, he began work at the University of Strasbourg under the renowned botanist Anton de Bary; Winogradsky became renowned for his work on sulfur bacteria.

In 1888, he relocated to Zurich, where he began investigation into the process of nitrification, identifying the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrosococcus, which oxidizes ammonium to nitrite, and Nitrobacter, which oxidizes nitrite to nitrate.

He returned to St. Petersburg for the period 1891–1905, and headed the division of general microbiology of the Institute of Experimental Medicine. During this period, he identified the obligate anaerobe Clostridium pasteurianum, which is capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen. In St. Petersburg, he trained his only student und assistant Vasily Omelianski which popularized Winogradskys concepts and methodology in the Soviet Union during the next decades.[7]

In 1901, he was elected honorary member of the Moscow Society of Naturalists and, in 1902, corresponding member of the French Academy of Sciences.

He retired from active scientific work in 1905, dividing his time between his private estate and Switzerland. In 1922, he accepted an invitation to head the division of agricultural bacteriology at the Pasteur Institute at an experimental station at Brie-Comte-Robert, France, about 30 km from Paris. During this period, he worked on a number of topics, among them iron bacteria, nitrifying bacteria, nitrogen fixation by Azotobacter, cellulose-decomposing bacteria, and culture methods for soil microorganisms. Winogradsky retired from active life in 1940 and died in Brie-Comte-Robert in 1953.

Discoveries

Winogradsky discovered various biogeochemical cycles and parts of these cycles. These discoveries include

- His work on bacterial sulfide oxidation for which he first became renowned, including the first known form of lithotrophy (in Beggiatoa).

- His work on the Nitrogen cycle including

- The identification of the obligate anaerobe Clostridium pasteurianum is a free living microbe capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen and not living in legume root nodules.

- Chemosynthesis – his most noted discovery

- The Winogradsky column[8]

Chemosynthesis

Winogradsky is best known for discovering chemoautotrophy, which soon became popularly known as chemosynthesis, the process by which organisms derive energy from a number of different inorganic compounds and obtain carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. Previously, it was believed that autotrophs obtained their energy solely from light, not from reactions of inorganic compounds. With the discovery of organisms that oxidized inorganic compounds such as hydrogen sulfide and ammonium as energy sources, autotrophs could be divided into two groups: photoautotrophs and chemoautotrophs. Winogradsky was one of the first researchers to attempt to understand microorganisms outside of the medical context, making him among the first students of microbial ecology and environmental microbiology.

The Winogradsky column remains an important display of chemoautotrophy and microbial ecology, demonstrated in microbiology lectures around the world.[9]

See also

Further reading

- Moshynets, O. (April 2013). "From Winogradsky's column to contemporary research using bacterial microcosms.". Microcosms: Ecology, Biological Implications and Environmental Impact. Harris, C.C. (eds.). Nova. pp. 1–27.

- Ackert, Lloyd. Sergei Vinogradskii and the Cycle of Life: From the Thermodynamics of Life to Ecological Microbiology, 1850-1950. Vol. 34.; Dordrecht; London: Springer, 2013.

- Ackert, L. (2006). "The Role of Microbes in Agriculture: Sergei Vinogradskii's Discovery and Investigation of Chemosynthesis, 1880–1910". Journal of the History of Biology. 39 (2): 373–406. doi:10.1007/s10739-006-0008-2.

- Ackert, L. (2007). "The 'Cycle of Life' in Ecology: Sergei Vinogradskii's Soil Microbiology, 1885–1940". Journal of the History of Biology. 40: 109–145. doi:10.1007/s10739-006-9104-6.

- Waksman, S. A. (1946). "Sergei Nikolaevitch Winogradsky: The study of a great bacteriologist". Soil Science. 62: 197–226. doi:10.1097/00010694-194609000-00001.

References

- Thornton, H. G. (1953). "Sergei Nicholaevitch Winogradsky. 1856-1953". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (22): 635–644. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1953.0022. JSTOR 769234.

- Waksman, S. A. (1953). "Sergei Nikolaevitch Winogradsky: 1856-1953". Science. 118 (3054): 36–37. Bibcode:1953Sci...118...36W. doi:10.1126/science.118.3054.36. PMID 13076173.

- Dworkin, M. (2012). Gutnick, David (ed.). "Sergei Winogradsky: A founder of modern microbiology and the first microbial ecologist". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 36 (2): 364–379. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00299.x. PMID 22092289.

- Winogradsky S (1887). "Über Schwefelbakterien". Bot. Zeitung (45): 489–610.

- Dworkin, Martin; Falkow, Stanley (2006). The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria: Proteobacteria: Gamma Subclass (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 784. doi:10.1007/0-387-30746-X_27. ISBN 978-0-387-25496-8.

- Waksman, Selman Abraham. 1953. Sergei N. Winogradsky: His Life and Work: The Story of a Great Bacteriologist. Rutgers University Press. p. 4

- Waksman, Selman A. (1928). "PROFESSOR V. L. OMELIANSKY". Soil Science. 26 (4): 255–256. doi:10.1097/00010694-192810000-00001. ISSN 0038-075X.

- Ogunseitan, Oladele (2005). Microbial Diversity: Form and Function in Prokaryotes (1st ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-4448-3.

- Madigan, Michael T. (2012). Brock biology of microorganisms (13th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780321649638.

External links

- Sergei Winogradsky at Cycle of Life website including images.