Charyapada

The Charyapada is a collection of mystical poems, songs of realization in the Vajrayana tradition of Buddhism from the tantric tradition in Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Odisha.[1][2][3]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

It was written between the 8th and 12th centuries in an Abahatta that was the ancestor of the Assamese, Bengali, Bhojpuri, Sylheti, Odia, Magahi, Maithili, and many other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, and it is said to be the oldest collection of verses written in those languages.[4][5][6] A palm-leaf manuscript of the Charyapada was rediscovered in the early 20th century by Haraprasad Shastri at the Nepal Royal Court Library.[7] The Charyapada was also preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist canon.[8]

As songs of realization, the Charyapada were intended to be sung. These songs of realisation were spontaneously composed verses that expressed a practitioner's experience of the enlightened state. Miranda Shaw describes how songs of realization were an element of the ritual gathering of practitioners in a ganachakra:

The feast culminates in the performance of tantric dances and music, that must never be disclosed to outsiders. The revellers may also improvise "songs of realization" (caryagiti) to express their heightened clarity and blissful raptures in spontaneous verse.[9]

Discovery

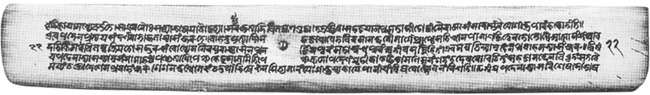

The rediscovery of the Charyapada is credited to Haraprasad Shastri, a 19th-century Sanskrit scholar and historian of Bengali literature who, during his third visit to Nepal in 1907, chanced upon 50 verses at the Royal library of the Nepalese kings. Written on trimmed palm leaves of 12.8×0.9 inches in a language often referred to as sāndhyabhāṣa or twilight language, a semantic predecessor of modern Bengali, the collection came to be called Charyapada and also Charyagiti by some. At that time, Shastri was a librarian of the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, and was engaged in a self-assigned mission to trace and track ancient Bengali manuscripts. His first and second trips to Nepal in 1897 and 1898 met with some success, as he was able to collect a number of folkloric tales written in Pali and Sanskrit. However, after he rediscovered the treasure manuscripts in 1907, he published this collections in a single volume in 1916. According to some historians, there may very likely have been at least 51 original verses which were lost due to absence of proper preservation.[10]

Manuscripts

The original palm-leaf manuscript of the Charyapada, or Caryācaryāviniścaya, spanning 47 padas (verses) along with a Sanskrit commentary, was edited by Shastri and published from Bangiya Sahitya Parishad as a part of his Hajar Bacharer Purano Bangala Bhasay Bauddhagan O Doha (Buddhist Songs and Couplets in a Thousands-Year-Old Bengali Language) in 1916 under the name of Charyacharyavinishchayah. This manuscript is presently preserved at the National Archives of Nepal. Prabodhchandra Bagchi later published a manuscript of a Tibetan translation containing 50 verses.[11]

The Tibetan translation provided additional information, including that the Sanskrit commentary in the manuscript, known as Charyagiti-koshavrtti, was written by Munidatta. It also mentions that the original text was translated by Shilachari and its commentary by Munidatta was translated by Chandrakirti or Kirtichandra.[12]

Poets

The manuscript of the Charyapada discovered by Haraprasad Shastri from Nepal consists of 47 padas (verses). The title-page, the colophon, and pages 36, 37, 38, 39, and 66 (containing padas 24, 25, and 48 and their commentary) were missing in this manuscript. The 47 verses of this manuscript were composed by 22 of the Mahasiddhas (750 and 1150 CE), or Siddhacharyas, whose names are mentioned at the beginning of each pada (except the first pada). Some parts of the manuscripts are lost; however, in the Tibetan Buddhist Canon, a translation of 50 padas is found, which includes padas 24, 25, and 48, and the complete pada 23. Pada 25 was written by the Siddhacharya poet Tantripāda, whose work was previously missing. In his commentary on pada 10, Munidatta mentions the name of another Siddhacharya poet, Ladidombipāda, but no pada written by him has been discovered so far.

The names of the Siddhacharyas in Sanskrit (or its Tibetan language equivalent), and the raga in which the verse was to be sung, are mentioned prior to each pada. The Sanskrit names of the Siddhacharya poets were likely assigned to each pada by the commentator Munidatta. Modern scholars doubt whether these assignments are proper, on the basis of the internal evidences and other literary sources. Controversies also exist among scholars as to the original names of the Siddhacharyas.

The poets and their works as mentioned in the text are as follows:

| Poet | Pada |

|---|---|

| Luipāda | 1,29 |

| Kukkuripāda | 2, 20, 48 |

| Virubāpāda | 3 |

| Gundaripāda | 4 |

| Chatillapāda | 5 |

| Bhusukupāda | 6, 21, 23, 27, 30, 41, 43, 49 |

| Kānhapāda | 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 18, 19, 24, 36, 40, 42, 45 |

| Kambalāmbarapāda | 8 |

| Dombipāda | 14 |

| Shantipāda | 15, 26 |

| Mahidharapāda | 16 |

| Vināpāda | 17 |

| Sarahapāda | 22, 32, 38, 39 |

| Shabarapāda | 28, 50 |

| Āryadevapāda | 31 |

| Dhendhanapāda | 33 |

| Darikapāda | 34 |

| Bhādepāda | 35 |

| Tādakapāda | 37 |

| Kankanapāda | 44 |

| Jayanandipāda | 46 |

| Dhāmapāda | 47 |

| Tantripāda | 25 |

Nature

The language of the Charyapada is rather symbolic in nature. So in many cases the literal meaning of a word does not make any sense. As a result, every poem has a descriptive or narrative surface meaning but also encodes tantric Buddhist teachings. Some experts believe this was to conceal sacred knowledge from the uninitiated, while others hold that it was to avoid religious persecution. Attempts have been made to decipher the secret tantric meanings of the Charyapada.[13] [14]

Period

Haraprasad Shastri, who rediscovered the Charyapada, conjectured that it was written during the 10th century. However, according to Suniti Kumar Chatterji, it was composed between 10th and 12th century. Prabodh Chandra Bagchi upholds this view. Sukumar Sen, while supporting this view, also states that the Charyapada could have been written between the 11th and 14th centuries.[15] However, Muhammad Shahidullah was of the opinion that the Charyapada dates back to an even earlier time. He maintained that it was likely to have been composed between 7th and 11th century.[16] Rahul Sankrityayan thought that the Charyapada was probably written between 8th and 11th century.

Controversies

There is controversy about the meaning of some words throughout the Charyapada. Different linguists have diverse opinions about the literal and figurative meanings of certain words.

It has been said that the Charyapada was written in an early form of Odia.[17]

Language

Haraprasad Shastri, in his introduction to the Charyacharya-vinishchaya, referred to the enigmatic language of its verses as "twilight language" (Sanskrit: Sandhya-bhasha), or Alo-andhari (half-expressed and half-concealed) based on the Sanskrit commentary of Munidatta. Vidhushekhara Shastri, on the basis of evidence from a number of Buddhist texts, later referred to this language as 'Intentional Language' (Sanskrit: Sandha-bhasha).[18]

The padas were written by poets from different regions, and it is natural that they would display linguistic affinities from these regions. Different scholars have noted the affinities of the language of the Charyapada with Assamese, Odia, Bengali, and Maithili.[19]

Affinities with Assamese

Luipa was from Kamarupa and wrote two charyas. Sarahapa, another poet, is said to have been from Rani, a place close to present-day Guwahati. Some of the affinities with Assamese are:[20]

Negatives – the negative particle in Assamese comes ahead of the verb: na jãi (No. 2, 15, 20, 29); na jivami (No. 4); na chadaa, na jani, na disaa (No. 6). Charya 15 has 9 such forms.

Present participles – the suffix -ante is used as in Assamese of the Vaishnava period: jvante (while living, No. 22); sunante (while listening, No. 30) etc.

Incomplete verb forms – suffixes -i and -iya used in modern and old Assamese respectively: kari (3, 38); cumbi (4); maria (11); laia (28) etc.

Present indefinite verb forms – -ai: bhanai (1); tarai (5); pivai (6).

Future – the -iva suffix: haiba (5); kariba (7).

Nominative case ending – case ending in e: kumbhire khaa, core nila (2).

Instrumental case ending – case ending -e and -era: uju bate gela (15); kuthare chijaa (45).

The vocabulary of the Charyapadas includes non-tatsama words which are typically Assamese, such as dala (1), thira kari (3, 38), tai (4), uju (15), caka (14) etc.

Affinities with Bengali

A number of Siddhacharyas who wrote the verses of Charyapada were from Bengal. Shabarpa, Kukkuripa and Bhusukupa were born in different parts of Bengal. Some of the affinities with Bengali are:[21]

Genitive -era, -ara;

Locative -Te;

Nominative -Ta;

Present indefinite verb -Ai;

Post-positional words like majha, antara, sanga;

Past and future bases -il-, -ib-;

Present participle -anta;

Conjunctive indeclinable -ia;

Conjunctive conditional -ite;

Passive -ia-

Substantive roots ach and thak.

Affinities with Odia

The beginnings of Odia poetry coincide with the development of Charya Sahitya, the literature thus started by Mahayana Buddhist poets.[22] This literature was written in a specific metaphor named “Sandhya Bhasha” and the poets like Kanhupa are from the territory of Odisha. The language of Charya was considered as Prakrita. In his book (Ascharya Charyachaya) Karunakar Kar has mentioned that Odisha is the origin of Charyapada as the Vajrayana school of Buddhism evolved there and started female worship in Buddhism. Worship of Matri Dakini and the practice of "Kaya sadhana" are the outcome of such new culture. Buddhist scholars like Lakshminkara and Padmasambhava were born in Odisha.[23] The ideas and experience of Kaya sadhana and Shaki upasana (worshiping female principle) which were created by Adi siddhas and have poetic expressions are found in the lyrics of Charyapada. These were the first ever found literary documentation of Prakrit and Apabhramsa which are the primitive form of languages of eastern Indian origin. The poets of Charyapada prominently are from this region and their thought and writing style has influenced the poems in early Odia literature which is evidently prominent in the 16th century Odia poetry written majorly in Panchasakha period.[24]

The language of Kanhupa's poetry bears a very strong resemblance to Odia. For example, :

Ekasa paduma chowshathi pakhudi

Tahin chadhi nachaa dombi bapudi

Paduma (Padma:Lotus), Chausathi (64), Pakhudi (petals) Tahin (there), Chadhi (climb/rise), nachaa (to dance), Dombi (an Odia female belonging to scheduled caste), Bapudi ( a very colloquial Odia language to apply as 'poor fellow' ) or

Hali Dombi, Tote puchhami sadbhabe.

Isisi jasi dombi kahari nabe.

Your hut stands outside the city

Oh, untouchable maid

The bald Brahmin passes sneaking close by

Oh, my maid, I would make you my companion

Kanha is a kapali, a yogi

He is naked and has no disgust

There is a lotus with sixty-four petals

Upon that the maid will climb with this poor self and dance.

some of the writing in Jayadeva's Gitagovinda have "Ardhamagadhi padashrita giti" (poetry in Ardhamagadhi) that is influenced by Charyagiti.[26]

Melodies

From the mention of the name of the Rāga (melody) for the each Pada at the beginning of it in the manuscript, it seems that these Padas were actually sung. All 50 Padas were set to the tunes of different Rāgas. The most common Rāga for Charyapada songs was Patamanjari.

| Raga | Pada |

|---|---|

| Patamanjari | 1, 6, 7, 9, 11, 17, 20, 29, 31, 33, 36 |

| Gabadā or Gaudā | 2, 3, 18 |

| Aru | 4 |

| Gurjari, Gunjari or Kanha-Gunjari | 5, 22, 41, 47 |

| Devakri | 8 |

| Deshākha | 10, 32 |

| Kāmod | 13, 27, 37, 42 |

| Dhanasi or Dhanashri | 14 |

| Rāmakri | 15, 50 |

| Balāddi or Barādi | 21, 23, 28, 34 |

| Shabari | 26, 46 |

| Mallāri | 30, 35, 44, 45, 49 |

| Mālasi | 39 |

| Mālasi-Gaburā | 40 |

| Bangāl | 43 |

| Bhairavi | 12, 16, 19, 38 |

While some of these Rāgas are extinct, the names of some of these Rāgas may actually be variant names of popular Rāgas we know today.[27]

Glimpses of social life

Many poems provide a realistic picture of early medieval society in eastern India and Assam (e.g. Kamarupa, by describing different occupations such as hunters, fishermen, boatmen, and potters). Geographical locations, namely Banga and Kamarupa, are referred to in the poems. Two rivers which are named are the Ganga and Yamuna. River Padma is also referred to as a canal. No reference to agriculture is available. References to female prostitution occur as well. The boat was the main mode of transport. Some description of wedding ceremonies are also given.[28]

Translations

Produced below is English translation of the first verse of the Charyapada. It was composed by Buddhist Siddhacharya poet Luipa.

The body is like the finest tree, with five branches.

Darkness enters the restless mind.

(Ka'a Tarubara Panchabee Dal, Chanchal Chi'e Paithe Kaal)

Strengthen the quantity of Great Bliss, says Luyi.

Learn from asking the Guru.

Why does one meditate?

Surely one dies of happiness or unhappiness.

Set aside binding and fastening in false hope.

Embrace the wings of the Void.

Luyi says : I have seen this in meditation

Inhalation and exhalation are seated on two stools.

Sarahapāda says :Sarah vonnoti bor sun gohali ki mo Duth Bolande

Meaning-It is better than empty Byre than a naughty Cow

Kānhapāda says :Apona Mangshe Horina Boiri

Meaning-Deer is enemy itself by its meat

This piece has been translated into English by Hasna Jasimuddin Moudud.[29]

Notes

- Tahmid, Syed Md. "Buddhist Charyapada & Bengali Identity". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The writers of the Charyapada, the Mahasiddhas or Siddhacharyas, belonged to the various regions of Assam, Bengal, Orissa and Bihar". sites.google.com. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Shaw, Miranda; Shaw, Miranda (1995). Passionate Enlightenment::Women in Tantric Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01090-8.

- Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language. p. 80.

- Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Subhra. Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow Press, UK. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8108-5334-8.

- Duggal, Gita; Chakrabarti, Joyita; George, Mary; Bhatia, Puja. Milestones Social Science. Madhubun. p. 79.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna; van Schendel, Willem (30 April 2013). The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-8223-5318-0.

- Kværne, Per (2010). An Anthology of Buddhist Tantric Songs: A Study of the Caryāgīti. Orchid Press. ISBN 978-974-8299-34-1.

- Shaw, Miranda (1995). Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-691-01090-0.

- Das, Dr. Nirmal (January 2014). Charyageeti Parikroma (in Bengali) (9th ed.). Dey’s Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-295-1600-8.

- Bagchi Prabodhchandra, Materials for a critical edition of the old Bengali Caryapadas (A comparative study of the text and Tibetan translation) Part I in Journal of the Department of Letters, Vol.XXX, pp. 1–156, Calcutta University, Calcutta,1938 CE

- Sen Sukumar (1995). Charyageeti Padavali (in Bengali), Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7215-458-5, pp.29–30

- Debaprasad Bandyopadhyay The Movement within: A Secret Guide to Esoteric Kayaasadhanaa: Caryaapada

- Debaprasad Bandyopadhyay In Search of Linguistics of Silence : Caryapada

- Sen Sukumar (1991) [1940]. Bangala Sahityer Itihas, Vol.I, (in Bengali), Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7066-966-9, p.55

- Muhammad Shahidullah : Bangala Bhashar Itibritto, 2006, Mawla Brothers, Dhaka

- Janaki Ballabha Mohanty (1988). An Approach to Oriya Literature: An Historical Study. Panchashila.

- Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol.IV, No.1, 1928 CE, pp.287–296

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (1960). The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI: The Delhi Sultanate. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 516, 519.

The Charyāpadas of Old Bengali have also been claimed for Old Assamese ... Some Oriyā scholars, like those of Assam, regard the speech of the Charyāpadas to be the oldest form of their language. The Maithils have also made the same claim.

- Language and Literature from The Comprehensive History of Assam Vol 1, ed H K Barpujari, Guwahati 1990

- Chatterjee, S.K. The Origin and Development of Bengali Language, Vol.1, Calcutta, 1926, pp.112

- Mukherjee, Prabhat. The History of medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. Chapter : The Sidhacharyas in Orissa Page:55.

- Kar. Karunakar. Ascharya Charyachaya

- Datta, Amaresh. The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume One (A To Devo)). Sahitya Akademi publications. ISBN 978-81-260-1803-1.

- Rajguru, Satyanarayan. Cultural History of Orissa (in Odia). Published by Orissa Sahitya Academy, 1988

- Parhi, Kirtan Narayan (May–June 2010). Orissa Review (PDF). Department of Culture, Government of Odisha. pp. 32–35.

- Roy, Niharranjan, Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba (in Bengali), Dey’s Publishing, Calcutta, 1993 CE, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, pp 637

- Social Life in Charjapad by Anisuzzaman

- Hasna Jasimuddin Moudud : A Thousand year of Bengali Mystic Poetry, 1992, Dhaka, University Press Limited.

References

- Dasgupta Sashibhusan, Obscure Religious Cults, Firma KLM, Calcutta, 1969, ISBN 81-7102-020-8.

- Sen Sukumar, Charyageeti Padavali (in Bengali), Ananda Publishers, 1st edition, Kolkata, 1995, ISBN 81-7215-458-5.

- Shastri Haraprasad (ed.), Hajar Bacharer Purano Bangala Bhasay Bauddhagan O Doha (in Bengali), Bangiya Sahitya Parishad, 3rd edition, Kolkata, 1413 Bangabda (2006).

Further reading

- Charyapada Translated by Dr. Tanvir Ratul, 2016, UK : Antivirus Publication.

- Charjapad Samiksha by Dr. Belal Hossain, Dhaka : Borno Bichitrra.

- Bangala Bhasar Itibrtta, by Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah, 1959, Dhaka.

External links

- Charyapada Translated by Tanvir Ratul