Château de Châteaubriant

The Château de Châteaubriant is a medieval castle strongly modified during the Renaissance, located in the commune of Châteaubriant in the Loire-Atlantique département of France.[1] The original castle was founded in the 11th century on the eastern border of Brittany and, such as the fortresses in Vitré, Fougères, Ancenis and Clisson, it was defending the duchy against Anjou and the Kingdom of France.

| Château de Châteaubriant | |

|---|---|

| Châteaubriant, France | |

The Renaissance facade on the moat. | |

| Coordinates | 47.72°N 1.373°W |

| Type | Castle, stately home |

| Site information | |

| Owner | General council of Loire-Atlantique |

| Open to the public | Limited |

| Condition | Mostly intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | 11th-16th century |

| Built by | Brient Ist of Châteaubriant |

| Materials | Sandstone, shale |

The castle was renovated several times during the Middle Ages and the town of Châteaubriant developed at its side. During the Mad War, the castle was seized by the French after a siege. The keep and the halls, partially destroyed, were renovated in the flamboyant style. Eventually, during the 16th century, the château obtained its definitive appearance when the new Renaissance palace was built against the medieval enceinte.

After the French Revolution, the château was sold and divided several times, and was finally transformed into an administrative centre, with the seat of the sous-préfecture, a court and a police station. All these offices closed down after 1970, and nowadays the château is partly opened to visitors.

Location

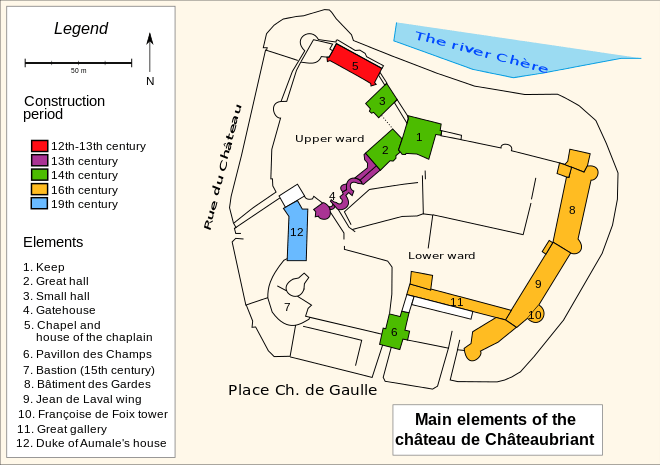

The château is located between the Châteaubriant-Rennes railway on the east and the old town centre on the west. To the north, it is bordered by the river Chère which forms a natural moat, and on the south by a wide square, the place Charles-de-Gaulle.

The Chère is retained by a medieval dam and forms a pond, the étang de la Torche. The dam serves as a bridge and it was originally an access to the walled town. A stream, the Rollard, also formed a moat on the western side of the castle. It was covered over during the 19th century and now flows under the town centre.

The subsoil in Châteaubriant is made of sedimentary rocks (schist and sandstone) belonging to the Armorican massif. These rocks form folds and outcrops.[2] The château is built on a promontory which is steep on the north, where the Chère flows, but slopes in terraces towards the south.

History

Middle Ages

The castle is first mentioned between 1030 and 1042 but it was founded earlier, at the beginning of the 11th century. It was first built by Brient, an envoy of the count of Rennes, to create an outpost in the Pays de la Mée. This region around Châteaubriant was then a buffer zone between the counties of Rennes, Nantes and Angers, but also a place for trading. The Béré fair was for example founded in 1049 in a suburb of the town. Brient is also responsible for the construction of the Béré church and priory, two major landmarks of medieval Châteaubriant.[3]

The first castle was a motte-and-bailey structure made of wood. It dominated the river Chère and the Rollard and had two concentric moats. One was dry, the other filled with water. It also had a big square keep, rebuilt in stone around 1100.[3] Two halls and a chapel were added during the 12th century, the latter being completed in the 13th century. In the same period, Châteaubriant emerged as a town on the banks of the Rollard. City walls were built between the 13th and the 15th centuries.[4]

The upper-ward gatehouse, the curtain wall and most of the towers were built during the 13th century. The gatehouse still includes its two towers which were originally 25 meters high. The halls and the keep were rebuilt in the 14th century, and the lower-bailey gatehouse was completed before 1400.[5]

The early House of Châteaubriant, whose founder was Brient, became extinct in 1383. The barony of Châteaubriant was then inherited by the House of Dinan, another Breton noble family. The Dinans found themselves without male offspring in 1444.[6] In 1486, the baroness of Châteaubriant, Françoise de Dinan, the last of her family, opposed Francis II of Brittany. She prepared the "Châteaubriant treaty" by which the barons of Brittany asked the King of France to settle a Breton internal dispute. The treaty, which betrayed the authority of Francis II, was one of the reasons for the Mad War and showed the weakness of the Duchy of Brittany as a political entity. Brittany and France went to war, Breton castles were taken one after the other by the French. Châteaubriant was besieged in 1488 and surrendered after one week.

At the end of the war, Françoise de Dinan had the castle restored and improved. As the old walls did not fit the new military exigences, a bastion was built. The keep and the halls, which also lost their defensive capacity, were opened by large windows. Inside, the baroness ordered new fireplaces in the Flamboyant style.[5]

Renaissance

The improvements on the keep and the halls were not sufficient for Françoise de Dinan who wanted a fashionable residence. She ordered a new palace, built in the lower bailey. This palace has been called Bâtiment des Gardes ("guards' building") since the French Revolution, because it was then used by the National Guard. The new residence was completed at the beginning of the 16th century, after the death of Françoise. At that time, Châteaubriant belonged to Jean de Laval, her grandson and a member of the House of Laval.[7]

However, Jean de Laval was not satisfied with the new palace, a stark building typical of the First Renaissance. He ordered a new wing, built around 1530 in an Italian style, and characteristic of the Second Renaissance. Jean de Laval is also responsible for the long gallery which forms an angle with the palace.[7]

Jean de Laval died heirless in 1543 and gave his possessions and titles to the Constable of France Anne de Montmorency, one of the most powerful Frenchmen of the time. The constable completed the works begun by Jean de Laval but established his residence at the Château d'Écouen, close to Paris.

Modern period

Châteaubriant belonged to the House of Montmorency until 1632 when Henri II de Montmorency was dispossessed and beheaded for felony. The barony was given to the Princes of Condé who kept it until the French Revolution.

The Condés slightly improved the château, for example in redesigning some rooms, such as the Chambre dorée in the Jean de Laval wing, decorated after 1632.[7] However, the princes did not live in Châteaubriant, but at the Château de Chantilly and in their hôtel particulier in Paris. The distance of the Dukes of Montmorency and later the Princes of Condé permitted the town council to gain some independence, but the lords still maintained local officers in the château.[8]

The roof of the keep collapsed after a storm around 1720. The building was not restored afterwards and slowly fell into ruin.[9]

Since the Revolution

The prince Louis V de Bourbon-Condé was one of the first nobles to go into exile during the French Revolution. He left France for England in 1789. The National Guard of the town settled in the château, which was also used to house various storehouses and a police station. Several parts of the buildings and courtyards were sold or rented to locals and the moat was partially filled in.[10]

During the Bourbon Restoration, the estate was progressively returned to the Prince of Condé. However, he eventually decided to sell it. The town council, in need of buildings for its jail, court and services, wanted to buy the château, but the prince did not wish to deal with the administration, and the mayor bought the property personally. He left the lower bailey gatehouse to the département, which transformed it into a jail, and sold the rest to the town council.[10] The mayor, Martin Connesson, also kept a part of the estate and built a new house on it in 1822.[10]

In 1839, the council considered pulling down the keep to use its stones to build a school and a bridge. This project met strong opposition and the château was included on the first list of monuments historiques in 1840.[9]

The town could not maintain the château in good repair and sold it to the Duke of Aumale in 1845.[10] The Duke settled in the house built by the mayor Martin Connesson and refurbished it.[11] Being a son of Louis-Philippe I, he followed his father to England after the Revolution of 1848 and sold the château to the Loire-Atlantique département in 1853.[9] The sous-préfecture moved there in 1854, and the 1822 house became the residence of the sous-préfet.[11] The police station, the court and the jail, which were relocated somewhere else after the Duke of Aumale acquired the estate, came back in 1855.[12][13]

In 1887, the département asked for the removal of the château from the monument historique list because it could not afford the repairs required by the authorities. However, several restoration campaigns were mounted after 1909, especially on the keep. The château was eventually reintegrated into the list in 1921.[9] In 1944, the southern end of the Renaissance palace was destroyed during an American bombing raid.[14]

Major restoration campaigns were carried out in the 1960s and after 2000.[9] Nonetheless, the château has never been fully opened to visitors, who can only access the wards and some rooms, such as the Chambre dorée and the Bâtiment des Gardes which hosts exhibitions. However, all the administration services progressively closed after 1970. For instance, the police station moved out in 1971, the public library followed in 2006, the sous-préfecture in 2012, and the court was closed in 2009. The house built by Martin Connesson remains the residence of the sous-préfet.

Architecture

The castle

The castle is divided between an upper ward and a lower bailey. The bailey, on the south, is opened by a 14th-century gatehouse, the Pavillon des Champs, which is the main entrance for the whole castle. The upper ward is accessible from the bailey through a second gatehouse. It is located on the highest point, dominating the Chère, and it is bordered by the seigniorial buildings: the two halls and the chapel.

The keep is built on both the upper and lower ward and also dominates the Chère. It was built in stone around 1100 on the site of the primitive motte. Later rebuilt in the 14th century, it felt into ruins during the 18th century. It forms an irregular square, its walls are 18 m long and 3.5 m thick. Remains of machicolation are visible on the top.[3] The two halls form an angle with the keep. They were rebuilt in the 14th century and the opening of new windows after the Mad War did not alter their austere look. The small hall, partially destroyed, has a peculiar roof, similar to a flat onion dome, made around 1562. The result is somewhat clumsy and is only an experimental attempt.[15]

Located close to the small hall, the chapel was built around 1142 and refurbished in the 13th century. Some hundred years later, it was divided in two and the western part was turned into the chaplain's house. The monument is romanesque but gothic windows were added in the 16th century.[3] The windows on the chaplain's house form a single bay culminating with a gothic dormer. Mural paintings and 15th-century floor tiles were discovered during archeological excavations.[5]

The gatehouse is partly ruined but it still has its two towers. It is built in sandstone with alternating lines of schist. Parts of the enceinte and the chemin de ronde are preserved.[3]

The Pavillon des Champs ("fields pavilion"), which opens the lower bailey, originally had a drawbridge. Its rear half was built in the 14th century and the front dates from the 16th century.[3]

- The keep. The great hall is located on the left, behind the trees.

The small hall.

The small hall. The chapel seen from outside the castle.

The chapel seen from outside the castle. The door of the chaplain's house.

The door of the chaplain's house.

The Renaissance palace

The Renaissance residence is located in the lower ward. It consist of an alignment of buildings built on the enceinte, with a gallery forming an angle.

Bâtiment des Gardes

The Bâtiment des Gardes is the oldest Renaissance building and also the less decorated. It was built around 1500. Its slate roof is steep and as tall as the facade itself, which gives a massive look to the whole. The facade is opened by large regularly positioned windows on the first floor and small irregular doors and windows on the ground floor. The facade on the moat is framed by two medieval towers which were opened by new large windows.

The walls are very thick and inside, the rooms are usually big. On the ground floor, the Salle verte ("green room"), which is the main hall, is 30 meters long and 10 meters large. It is also 10 meters high and its monumental fireplace is two meters wide. The local blue schist was largely used as an ornamental material; it is particularly visible on ceilings, fireplaces and around the windows.[16]

Jean de Laval wing

The Jean de Laval wing was designed by Jean Delespine, a local architect, and built after 1532. At that time, French architecture had changed a lot: medieval features still in use at the beginning of the 16th century were totally rejected for Italian designs. Thus the Jean de Laval wing is fully different from the Bâtiment des Gardes. It is opened on the bailey by large windows bordered by tuff pilasters and small niches and it has Italian sculpted dormers. On the external facade, the architect reemployed the medieval walls and towers and opened them with large windows and dormers. Although very Italian in design, the building retained some French typical features, such as a steep slate roof and high chimneys. The design is also messy on several details, for example, the windows are not perfectly regular and some of them are too close to each other. Tuff, extremely common on the châteaux in the Loire Valley, because it is easily found there, had to be imported to Châteaubriant and was only used for ornamental purpose. Instead, the walls were built with local sandstone and the facade on the bailey was covered by a white coating. Local blue schist was also used for the niches and the chimneys alternate tuff and bricks.

A monumental staircase was built at the junction between the Jean de Laval wing and the Bâtiment des Gardes. It served as the main entrance and its first floor is opened by a loggia. The staircase was built with tuff and its vaults are decorated with little schist coffers.[16]

The Chambre dorée ("golden room"), the only room opened to visitors, is located on the first floor. It was decorated in the 1630s with red tapestry and baroque sculptures. The overmantel of the fireplace is particularly rich, with an oil on canvas and golden cornucopias.[16]

The Jean de Laval wing. The staircase is on the left.

The Jean de Laval wing. The staircase is on the left. The vault of the staircase.

The vault of the staircase. A door in the staircase.

A door in the staircase.

The great gallery

The great gallery was originally closing the garden in front of the Jean de Laval wing and it was connecting it to the keep. Only one wing has been preserved, but several remains such as columns are still visible in the garden. The remaining part comprises two levels and the walls are made of red bricks whereas the decorative details are made of blue schist. The combination of these two materials is rare and creates a quaint look. The ground floor is a loggia opened by 21 arches with doric columns. The first floor is opened by large windows with small pediments. This floor is accessible through a stair located in an adjoining pavilion.[16]

The gallery.

The gallery.- View from the pavilion.

Legends

Two legends are linked with the château. The first one involves Sybille, the wife of Geoffroy IV of Châteaubriant, who went on Crusade in 1252. He was jailed in Egypt in 1250 and the French army was destroyed there by the plague. The same year, the death of Geoffroy was announced in Châteaubriant, and Sybille started to mourn him. However, he would have come back several months later. Because of the shock, Sybille would have succumbed in his arms.[17]

The second legend involves Jean de Laval and his wife, Françoise de Foix. They were engaged in 1505 with the support of Anne de Bretagne, duchess of Brittany and Queen of France. After the death of Anne and her husband Louis XII of France, the new King, Francis I, asked Jean de Laval to come to his Court to help him settle the French annexation of Brittany. Françoise de Foix followed her husband and became the lady in waiting to the Queen Claude de France as well as the mistress of Francis I. Jean fought in the Italian Wars and became Governor of Brittany in 1531. Françoise de Foix was on her side rejected from the Court in 1525.[18]

She died on 16 October 1537, during the night, and assassination rumors quickly spread. According to them, Françoise would have been killed by her husband, jealous of her relationship with the King. According to some rumors, Jean de Laval would also have locked up his wife in a room, and later poisoned her or bled her to death. Since then, every 16 October at midnight, a ghost procession would walk in the château. The Chambre dorée has often been presented as the place where Françoise died, but its present layout dates from only the 17th century.[18]

References

- Ministry of Culture: Château (in French)

- L'histoire géologique de la Bretagne Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, Emmanuèle Savelli

- Châteaubriant.org (ed.). "Le château médiéval".

- Ministry of Culture: Fortification d'agglomération (in French)

- Pays de Châteaubriant (ed.). "Le château médiéval". Archived from the original on 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- Jean-Luc Flohic; Éric Brochard; Véronique Daboust (1999). Le Patrimoine des communes de la Loire-Atlantique. 1. Flohic. p. 257.

- Pays de Châteaubriant (ed.). "Le château de la Renaissance". Archived from the original on 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- Châteaubriant.org (ed.). "Une ville close à l'abri du château".

- Ouest-France, ed. (15 December 2012). "Pourquoi on bichonne le château de Châteaubriant - Châteaubriant".

- Charles Goudé (1870). "Châteaubriant, baronnie, ville et paroisse, Chapitre VI (suite)". Amaury de la Pinsonnais.

- Conseil général de la Loire-Atlantique (ed.). "La sous-préfecture".

- Conseil général de la Loire-Atlantique (ed.). "La gendarmerie".

- Conseil général de la Loire-Atlantique (ed.). "La prison".

- Châteaubriant.org (ed.). "Livre - Les bombardements de Châteaubriant" (PDF).

- Dendrotech (ed.). "Une charpente à l'impériale : le Petit Logis à Chateaubriant (Loire-Atlantique)".

- Châteaubriant histoire; journal La Mée (eds.). "Le château Renaissance".

- Loire-Atlantique (ed.). "Sybille".

- Pays de Châteaubriant (ed.). "Chambre dorée de Françoise de Foix". Archived from the original on 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2013-02-22.