Cecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The word cecum (/ˈsiːkəm/, plural ceca /ˈsiːkə/) stems from the Latin caecus meaning blind.

| Cecum | |

|---|---|

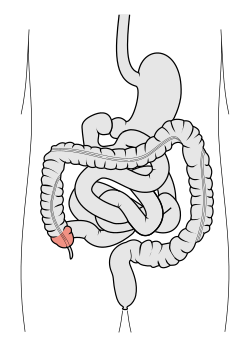

The cecum, here in red, lies at the start of the large intestines, which are shown with the rest of the human gastrointestinal tract in this image. | |

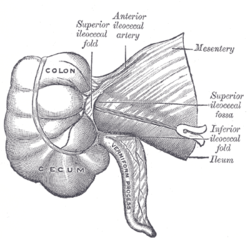

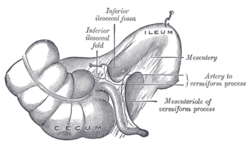

Superior ileocecal fossa (cecum labeled at bottom left) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Midgut |

| Part of | Large intestine |

| System | Gastrointestinal |

| Location | Lower right part of the abdomen. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Caecum |

| MeSH | D002432 |

| TA | A05.7.02.001 |

| FMA | 14541 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

It receives chyme from the ileum, and connects to the ascending colon of the large intestine. It is separated from the ileum by the ileocecal valve (ICV) or Bauhin's valve. It is also separated from the colon by the cecocolic junction. While the cecum is usually intraperitoneal, the ascending colon is retroperitoneal.[1]

In herbivores, the cecum stores food material where bacteria are able to break down the cellulose. This function no longer occurs in the human cecum (see appendix), so in humans it is simply a dead-end pouch forming a part of the large intestine.

Structure

Development

The cecum and appendix are formed by the enlargement of the postarterial segment of the midgut loop. The proximal part of the bud grows rapidly to form the cecum. The lateral wall of the cecum grows much more rapidly than the medial wall, with the result that the point of attachment of the appendix comes to lie on the medial side.

History

Etymology

The term cecum comes from the Latin (intestinum) caecum, literally "blind intestine", here in the sense "blind gut" or "cul de sac". It is a direct translation from Ancient Greek τυφλὸν (ἔντερον) - typhlòn (énteron). Thus the inflammation of the cecum is called typhlitis.

In dissections by the Greek philosophers, the connection between the ileum of the small intestines and the cecum was not fully understood. Most of the studies of the digestive tract were done on animals and the results were compared to human structures.

The junction between the small intestine and the colon, called the ileocecal valve, is so small in some animals that it was not considered to be a connection between the small and large intestines. During a dissection, the colon could be traced from the rectum, to the sigmoid colon, through the descending, transverse, and ascending sections. The cecum is an end point for the colon with a dead-end portion terminating with the appendix.[3]

The connection between the end of the small intestine (ileum) and the start (as viewed from the perspective of food being processed) of the colon (cecum) is now clearly understood, and is called the ileocolic orifice. The connection between the end of the cecum and the beginning of the ascending colon is called the cecocolic orifice.

Clinical significance

A cecal carcinoid tumor is a carcinoid tumor of the cecum. An appendiceal carcinoid tumor (a carcinoid tumor of the appendix) is sometimes found next to a cecal carcinoid.

Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) is the condition of inflammation of the cecum, primarily caused by bacterial infections.

Over 99% of the bacteria in the gut are anaerobes, but in the cecum, aerobic bacteria reach high densities.[4]

Other animals

A cecum is present in most amniote species, and also in lungfish, but not in any living species of amphibian. In reptiles, it is usually a single median structure, arising from the dorsal side of the large intestine. Birds typically have two paired ceca, as, unlike other mammals, do hyraxes.[5] Parrots do not have ceca.[6]

Most mammalian herbivores have a relatively large cecum, hosting a large number of bacteria, which aid in the enzymatic breakdown of plant materials such as cellulose; in many species, it is considerably wider than the colon. In contrast, obligatory carnivores, whose diets contain little or no plant material, have a reduced cecum, which is often partially or wholly replaced by the appendix.[5] Mammalian species which do not develop a cecum include raccoons, bears, and the red panda. Over 99% of the bacteria in the gut flora are anaerobes,[7][8][9][10][11] but in the cecum, aerobic bacteria reach high densities.[7]

Many fish have a number of small outpocketings, called pyloric ceca, along their intestine; despite the name they are not homologous with the cecum of amniotes, and their purpose is to increase the overall area of the digestive epithelium.[5] Some invertebrates, such as squid,[12] may also have structures with the same name, but these have no relationship with those of vertebrates.

Gallery

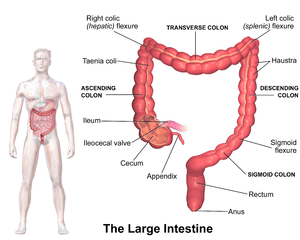

Illustration of the large intestine

Illustration of the large intestine- Cecum and ileum

- Ileo-cecal valve

- Cecum

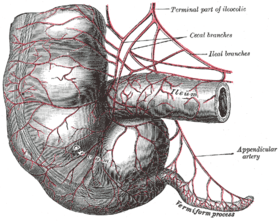

Arteries of cecum and vermiform process

Arteries of cecum and vermiform process Inferior ileocecal fossa

Inferior ileocecal fossa Endoscopic image of cecum with arrow pointing to ileocecal valve in foreground

Endoscopic image of cecum with arrow pointing to ileocecal valve in foreground

See also

References

- "The Large Intestine". VideoHelp.com.

- Nguyen H, Loustaunau C, Facista A, Ramsey L, Hassounah N, Taylor H, Krouse R, Payne CM, Tsikitis VL, Goldschmid S, Banerjee B, Perini RF, Bernstein C (2010). "Deficient Pms2, ERCC1, Ku86, CcOI in field defects during progression to colon cancer". J Vis Exp (41). doi:10.3791/1931. PMC 3149991. PMID 20689513.

- Taylor, Tim. "Anatomy and Physiology Instructor". InnerBody.com. Howtomedia, Inc. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Sherwood, Linda; Willey, Joanne; Woolverton, Christopher (2013). Prescott's Microbiology (9th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 713–21. ISBN 9780073402406. OCLC 886600661.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 353–54. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Clench, Mary H.; Mathias, John R. (1995). The Avian Cecum: A Review. Ann Arbor, MI: Wilson Bulletin. pp. 93–121, vol. 107(1) March.

- Guarner F, Malagelada JR (February 2003). "Gut flora in health and disease". Lancet. 361 (9356): 512–19. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0. PMID 12583961.

- Sears CL (October 2005). "A dynamic partnership: celebrating our gut flora". Anaerobe. 11 (5): 247–51. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2005.05.001. PMID 16701579.

- University of Glasgow. 2005. The normal gut flora. Available through web archive. Accessed May 22, 2008

- Beaugerie L, Petit JC (April 2004). "Microbial-gut interactions in health and disease. Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 18 (2): 337–52. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2003.10.002. PMID 15123074.

- Vedantam G, Hecht DW (October 2003). "Antibiotics and anaerobes of gut origin". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6 (5): 457–61. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2003.09.006. PMID 14572537.

- Williams, L. W. (1910). The anatomy of the common squid : Loligo pealii, Lesueur. American Museum Of Natural History.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cecum. |

| Look up cecum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Photo at mgccc.cc.ms.us

- Anatomy figure: 37:03-08 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"Abdominal organs in situ."

- Anatomy figure: 37:06-09 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"The larger intestine."

- Anatomy figure: 39:05-09 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"The cecum with the distal portion of the ileum."

- Anatomy photo:39:14-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"Incisions of the Cecum"

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-2—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Video clip of worms in the Cecum