Cave Junction, Oregon

Cave Junction, incorporated in 1948, is a city in Josephine County, Oregon, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 1,883.[6] Its motto is the "Gateway to the Oregon Caves",[7] and the city got its name by virtue of its location at the junction of Redwood Highway (U.S. Route 199) and Caves Highway (Oregon Route 46).[8] Cave Junction is located in the Illinois Valley, where, starting in the 1850s, the non-native economy depended on gold mining. After World War II, timber became the main source of income for residents. As timber income has since declined, Cave Junction is attempting to compensate with tourism and as a haven for retirees. Tourists visit the Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve, which includes the Oregon Caves Chateau, as well as the Out'n'About treehouse resort and the Great Cats World Park zoo.

Cave Junction, Oregon | |

|---|---|

Entering town from the North | |

| Motto(s): Gateway to the Oregon Caves | |

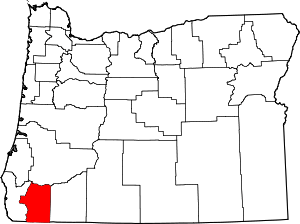

Location in Oregon | |

| Coordinates: 42°10′0″N 123°38′49″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Josephine |

| Incorporated | 1948 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Meadow Martell |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.81 sq mi (4.70 km2) |

| • Land | 1.81 sq mi (4.68 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,575 ft (480 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,883 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 1,977 |

| • Density | 1,092.87/sq mi (422.06/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP codes | 97523, 97531 |

| Area code(s) | 458 and 541 |

| FIPS code | 41-11850[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1139474[5] |

| Website | www.cavejunctionoregon.us |

History

For thousands of years, the Takelma Indians inhabited the Illinois Valley.[9] Their culture was destroyed when gold was discovered in the early 1850s, causing the subsequent Rogue River Wars. After an 1853 treaty, most of the Takelmas lived on the Table Rock Reservation. In 1856, after the wars ended, they were moved to the Grand Ronde Reservation and the Siletz Reservation.[10]

The first gold in Oregon history was found in the Illinois Valley, as well as the largest gold nugget (17 lb or 7.7 kg).[11] In 1904, more than 50 years after prospectors had started combing the valley for gold, an 18-year-old named Ray Briggs discovered what newspapers at the time called "the most wonderful gold discovery ever reported in Oregon history." While hunting along Sucker Creek, he discovered gold lying on the ground. He staked a claim and called it the "Wounded Buck Mine," which produced 1,777 ounces (50.4 kg) of gold. The "mine" was a small vein of gold 12 to 14 inches (30 to 36 cm) wide, 12 feet (3.7 m) long and 7 feet (2.1 m) deep.[11]

As gold mining in the Illinois Valley became exhausted in the 1860s and 1870s, the residents diversified into ranching, fishing, logging, tourism and agriculture.[12] In 1874, Elijah Davidson found a cave while on a hunting trip, and is now credited with discovering the Oregon Caves. In 1884, Walter C. Burch heard about the cave from Davidson, and staked a squatter's claim at the mouth of the caves. He and his brothers-in-law charged one dollar for a guided tour. According to their advertisement in the Grants Pass Courier, this included camping, plentiful pasture land and "medicinal" cave waters. They attempted to acquire title to the land, but as the land was unsurveyed, they abandoned the idea a few years later.[9]

President William Howard Taft established the 480-acre (190 ha) Oregon Caves National Monument on July 12, 1909, to be administered by the U.S. Forest Service. In 1923, the Forest Service subcontracted the building of a hotel and guide services to a group of Grants Pass businessmen. By 1926, the monument had a chalet and seven two-bedroom cabins.[9] Traffic into the caves led to a community developing at the junction of the Redwood Highway and the branch highway to the caves (now known as Oregon Route 46).[13] Cave Junction, originally known as Cave City, was established in 1926 on land donated by Elwood Hussey.[9][14] In 1935, a post office was applied for and was named "Caves City", however postal authorities disapproved of the name, partly because "City" implied the place was incorporated.[13] Among the other names suggested was "Cave Junction", which was adopted by the United States Board on Geographic Names in 1936 with the post office being renamed the same year.[13] The locality was incorporated as Cave Junction in 1948, and is the only incorporated area in the Illinois Valley.[8]

In 1950 Cave Junction had a population of 283, which decreased to 248 in 1960 and increased to 415 in 1970. Its growth was fast in the 1960s, increasing at an average of 6.8 percent annually. The city population's primary growth period occurred in the 1970s, with an average annual increase of 9.9 percent. Growth slowed in the 1980s when the population increase averaged only 1.7 percent annually. The rate fell further between 1990 and 1998, averaging 1.6 percent, which was less than the state and county averages.[15]

Forest fires

A number of wildfires have threatened Cave Junction over the years. The Longwood Fire in 1987, part of the 150,000-acre (61,000 ha) Silver Fire complex, was ignited by lightning strikes following a three-year drought. Numerous residents of Cave Junction evacuated.[16]

In 2002, the Florence and Sour Biscuit fires converged, creating the Biscuit Fire. This fire threatened Cave Junction, Kerby, Selma and a number of Northern California communities.[17] Ultimately, the Biscuit Fire lasted 120 days, burned 499,965 acres (202,329 ha) in southern Oregon and northern California, and destroyed four homes and nine outbuildings in the Cave Junction area.[18] In 2003, a wildfire destroyed a home in Cave Junction.[19] In 2004, a downed power line caused a fire that briefly threatened over 100 homes and forced 200 people to evacuate. One person died, apparently of stress related to the fire.[20]

Geography

Cave Junction is located on U.S. Route 199 at its junction with Oregon Route 46. It is about 30 miles or 48 kilometres southwest of Grants Pass, Oregon and 53 miles or 85 kilometres northeast of Crescent City, California. The city lies in the Illinois Valley, on the northwest slope of the Siskiyou Range, at an elevation of about 480 metres (1,570 ft) above MSL. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.82 square miles (4.71 km2), of which, 1.81 square miles (4.69 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[21]

Climate

Cave Junction has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb) with summers featuring cool mornings and hot afternoons, and chilly, rainy winters.

Cave Junction has an average low of 32.5 °F or 0.3 °C in January and high of 90.5 °F or 32.5 °C in July. The record hottest temperature is 114 °F (45.6 °C) on August 14, 2008; however, the hottest morning on record is a mere 69 °F (20.6 °C) on July 21, 1994 and July 3, 2013. The coldest temperature is −6 °F (−21.1 °C) on December 10, 1972, and the only other mornings below 0 °F or −17.8 °C were on the adjacent mornings of December 8 and 10 that year. Only sixteen afternoons have ever failed to top freezing; the coldest afternoon being 21 °F (−6.1 °C) on the same day as the record cold minimum. The coldest month since 1962 has been December 2013 which averaged 32.9 °F (0.5 °C) and had a mean maximum of only 40.6 °F (4.8 °C).

On average, there are 196 sunny days, and 108 days with precipitation. The city receives an average of 60.48 inches or 1,536.2 millimetres of rain each year.[22][23] The wettest "rain year" has been from July 1973 to June 1974 with 103.21 inches (2,621.5 mm), and the driest from July 1976 to June 1977 with 24.87 inches (631.7 mm).[24] The wettest month has been December 1996 with 35.29 inches (896.4 mm), and the wettest day December 22, 1964 with 8.12 inches (206.2 mm).

Snowfall averages 14.3 inches or 0.36 metres; the most snowfall in one month has been 60.0 inches (1.52 m) in January 1982 and the most in one season 83.9 inches (2.13 m) from July 1981 to June 1982. The most snowfall in one day has been 25.0 inches or 0.64 metres on January 3 and again on January 18 of 1982.[24]

| Climate data for Cave Junction | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

98 (37) |

108 (42) |

109 (43) |

112 (44) |

114 (46) |

110 (43) |

100 (38) |

78 (26) |

69 (21) |

114 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.6 (8.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

58.5 (14.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

73.4 (23.0) |

81.4 (27.4) |

90.5 (32.5) |

90 (32) |

84.2 (29.0) |

70.2 (21.2) |

53.4 (11.9) |

46.5 (8.1) |

67.8 (19.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 32.5 (0.3) |

33.5 (0.8) |

34.6 (1.4) |

36.5 (2.5) |

41.2 (5.1) |

46.6 (8.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

49.2 (9.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

39 (4) |

36.7 (2.6) |

33 (1) |

39.8 (4.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 11 (−12) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

21 (−6) |

27 (−3) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

34 (1) |

25 (−4) |

15 (−9) |

11 (−12) |

−6 (−21) |

−6 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 10.92 (277) |

8.05 (204) |

7.74 (197) |

4.03 (102) |

2.03 (52) |

0.75 (19) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.49 (12) |

0.98 (25) |

3.63 (92) |

9.38 (238) |

12.25 (311) |

60.48 (1,536) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

3.5 (8.9) |

1.8 (4.6) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

3.2 (8.1) |

14.3 (36) |

| Average precipitation days | 15 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 16 | 110 |

| Source: [25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1950 | 283 | — | |

| 1960 | 248 | −12.4% | |

| 1970 | 415 | 67.3% | |

| 1980 | 1,023 | 146.5% | |

| 1990 | 1,126 | 10.1% | |

| 2000 | 1,360 | 20.8% | |

| 2010 | 1,883 | 38.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 1,977 | [3] | 5.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 1,883 people, 815 households, and 469 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,040.3 inhabitants per square mile (401.7/km2). There were 916 housing units at an average density of 506.1 per square mile (195.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.3% White, 0.4% African American, 2.0% Native American, 1.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.9% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.3% of the population.

There were 815 households, of which 26.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.9% were married couples living together, 13.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 42.5% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.94.

The median age in the city was 43 years. 23.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 19.1% were from 25 to 44; 27.4% were from 45 to 64; and 21% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.0% male and 54.0% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 1,363 people, 603 households, and 356 families residing in the city. The population density was 828.8 people per square mile (320.9/km2). There were 730 housing units at an average density of 443.9 per square mile (171.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.3% White, 0.3% African American, 2.1% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 1.2% other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.6% of the population.

There were 603 households, out of which 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.8% were married couples living together, 14.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.8% were non-families. 33.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 20.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.87.

In the city, the age population was spread out, with 26.8% under the age of 18, 7.7% from 18 to 24, 21.9% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 21.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $17,161, and the median income for a family was $22,500. Males had a median income of $20,893 versus $16,333 for females. The per capita income for the city was $10,556. About 23.6% of families and 28.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 35.8% of those under age 18 and 11.9% of those age 65 or over.

Government and politics

Residents range from very liberal, to strongly right-wing to survivalists.[27] As of 2002, the city has 13 employees, with an average wage of $35,799, the largest categories of employees are Sewerage and Water Supply, with four employees each. In total, Cave Junction's monthly employee outlay is $35,799, or $465,384 a year.[28] As of 2007, Josephine County Sheriff volunteers man a sub station in Cave Junction, and the Sheriff's Office has plans to begin a pilot program in the City Hall building, staffed by volunteers, that will include three temporary holding cells and the ability to take incident reports.[29]

Economy

Starting in the early 1850s, gold mining was the main source of income in the Illinois Valley. As gold mining dwindled in the 1860s and 1870s, the economy diversified into ranching, fishing, logging, tourism and agriculture. In the years after World War II, timber became an increasingly large part of the county's finances.[12] There were 30 lumber mills operating in the valley after the war, but by the late 1980s the number had dwindled to just one.[30]

Because of President Roosevelt's creation of the Siskiyou National Forest, and the reversion of Oregon and California Railroad lands to federal government control, by 1937 the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management were in charge of 70% of the land in Josephine county, and a large part of the Illinois Valley. Because this decreased the county's potential tax base, the government shared money earned from timber sales with the county,[31] and payments in lieu of taxes from the federal government became a large part of its tax base. In 1989, Josephine County received $16,756,000 in various federal payments; by 1999, the payments had fallen to $9.6 million.[12]

Because of these budget cutbacks, Southern Oregon has used tourism as a means of attracting small businesses and retirees.[32] The movement of California retirees in particular has helped the economy grow.[33] Although jobs have been created as a result, they are usually low-paying.[32] Today the principal industries are tourism, timber and agriculture.[34] Since about 1960, the community has evolved into a center for wine, retirement, tourism, and small businesses.[35] In November 2007, Rough & Ready completed a $6 million biomass plant to replace their existing wood-fired boiler, as market forces have increased demand for dry timber.[36] It finally closed in November, 2016.

The Illinois Valley Community Development Organization (IVCDO), formed in 1994, has attracted notice for its work directed at improving the Illinois Valley economy. In 2006, Cave Junction was awarded the Great Strides Award by the Northwest Area Foundation for the IVCDO's efforts to reduce long-term poverty. In 2004, the IVCDO began a partnership with the National Park Service that resulted in the assumption of 40 seasonal and year-around jobs managing the Oregon Caves Chateau. The project uses local produce, food products and wine at the Chateau, and the proceeds are directed back into the local community.[37]

Culture

Cave Junction has a number of points of interest, including a museum, a zoo, and a resort consisting of treehouses. It also has a number of historic sites, many related to gold mining, as well as an Oregon state park and a national monument and preserve, all located in the greater Cave Junction area. A newspaper and one radio station.

Tourism

Cave Junction's main point of interest is the Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve, which is a 4,554-acre (1,843 ha) area of hiking trails and caverns. Located at the end of a 20-mile (32 km) "stomach churning" drive along State Route 46, there are limestone caves discovered in 1874 by a hunter and his dog. At the caves, there is a 23-room chateau that was built in 1932.[38]

Each year Cave Junction features an ArtWalk on the second Friday of each month, except during the winter, with the city's businesses exhibiting various types of art such as pottery, iron art, music and fire dancing.[39] The ArtWalk adds significantly to the Illinois Valley's positive image and increases tourism and adds to the local economy. According to surveys conducted in 2006 by the Arts Council of Southern Oregon, the city sees a 30–50 percent increase in sales and visitors during the event. Attendance is approximately 150–200 people, with roughly 15 percent coming from outside the community.[40] Local artists, including students of Lorna Byrne Middle School in 2007,[41] participate while local businesses, including thrift stores and art galleries, serve as hosts.[39]

Located about 10 miles (16 km) southeast of Cave Junction,[42] in Takilma, Oregon, is the home of the Out'n'About Treehouse Treesort, a multi-treehouse resort run by Michael Garnier using Garnier limbs. Garnier developed the Garnier limb, which is a one-and-a-half-inch-thick bolt surrounded by a cuff, both made of Grade 5 steel, and is able to support 8,000 lb (3,600 kg). As of 2007, the treesort has nine treehouses, three with bathrooms.[43][44] Garnier had to fight local government ordinances for almost ten years before gaining the right to house guests in his nine treehouses.[45]

Great Cats World Park is located a few miles south of Cave Junction. As of 2007, it has 32 cats, of 17 different species, including cougars, leopards, jaguars, lions, Siberian tiger cubs, a fishing cat, and an ocelot.[46][47][48] Other attractions include the It's a Burl handcrafted wood gallery and the Kerbyville Museum, both in Kerby.[49] Cave Junction's Wild River Brewery serves one of the smallest communities of any Oregon brewery.[50] Founded in 1975 as the Pizza Deli, a microbrewery was added in 1989. In 1994, the name Wild River was adopted and a Wild River restaurant and pub was opened in Grants Pass.[51]

Wine

The Illinois Valley is the coolest and wettest of the three valleys in the Rogue Valley American Viticultural Area.[52] In the late 1960s and early 1970s a new group of Oregonians started experimenting with growing grapes and making wine. Initially this group was not very successful, but 40 years later, Oregon is considered a prestigious growing area.[53] Southern Oregon is higher, and its climate is often warmer, than better known wine producing valleys such as Napa Valley to the south and Willamette Valley and Columbia Valley to the north.[54] The Illinois Valley has dry warm summers and cold nights, which make it well suited for pinot noir, in contrast to the hotter and drier Rogue and Umpqua valleys.[53] Several vineyards and wineries are located near Cave Junction, including Bridgeview Vineyards, Foris Vineyards Winery, and Bear Creek Winery which are all discussed in Fodor's 2004 book "Oregon Wine Country."[55][56]

Cave Junction is the home of Bridgeview Vineyards, one of the largest wineries in Oregon.[57] Bridgeview is noted for its chardonnay, pinot gris and pinot noir. At the 2000 American Wine Awards, Bridgeview's 1998 Bridgeview Oregon Blue Moon was selected as the best pinot noir under $15.[58] Its 85-acre (34 ha) estate in the Illinois Valley is planted in the European style of dense 6-foot (1.8 m) row and 4-foot (1.2 m) vine spacing. Bridgeview also has an 80-acre (32 ha) vineyard in the Applegate Valley.[59] Foris Vineyards Winery is also located in the Cave Junction area. Established in 1986,[60] as of 2007, they produced 48,000 cases of wine, making it the 14th largest bonded winery in Oregon.[51]

Historic sites

Cave Junction has a number of historic sites related to its early gold mining days, including various mines, ditches, and Logan Cut.[61] The historic Osgood Ditch in Takilma provided water for early mining operations in the Illinois Valley.[62] Although mining in the Illinois Valley started in the rivers, gold was soon discovered in gravel beds high up the slopes above the rivers. It had been deposited by ancient rivers that then eroded deep into the earth. To extract this gold, prospectors created ditches to bring the water to these areas. The water was then moved through piping to the desired location. The pressure the water built up as it dropped was used for hydraulic mining. Water cannons fired water over 100 feet (30 m), and the debris was run through a sluice box. Gold was located within pockets in the gravel, and because the miners could not predict where the pockets were, almost every gravel deposit in the Illinois Valley was mined. The Illinois Valley's largest gold rush town, Waldo, Oregon, was located on a gravel deposit and was eventually destroyed when its gravel bed was run through a sluice box, along with most of the town. Today nothing of Waldo remains. The Osgood Ditch provided water for mining operations near Waldo.[63] One building of note in the area is the Oregon Caves Chateau, which is a National Historic Landmark.[64]

One of the well known mining communities AltHouse established the AltHouse Church in 1893 about a 1/4 mile down on Dick George Road. This church is one of the oldest building in the valley still standing and still in use. Between 1895–99 the church was moved down to its present site on Holland Loop Road where it has served the community till this day. It is currently known as Bridgeview Community Church (since the 1920s). A newer building was built in 1986 where services are now being held every Sunday. The original church is currently under restoration and will continue to be as the builders back then said; "A place for us or children and grandchildren to worship".[65]

Sports and recreation

Cave Junction has a golf course and a state park. The Illinois Valley Golf Course has 9 holes, and as of 2007 there are plans for an expansion to 18 holes.[49][66][67] The Illinois River Forks State Park is located at the confluence of the east and west forks of the Illinois River. The park includes restrooms, picnic tables, and a variety of rare plants.[68] In 2014 a new disc golf course was built at the Illinois River Forks State Park. There is also a skate park at Jubilee Park in Cave Junction, which was built largely by volunteers and money raised through fundraisers and community involvement.

Media

Cave Junction has one newspaper and two radio stations. The local paper, the Illinois Valley News, is a paper of record for all of Josephine County. Established in 1937 when Cave Junction was known as Cave City, and as of 2018 has a circulation of 2,280. The Valley's longest running business is published every Wednesday by Daniel J. Mancuso and edited by Laura M. Mancuso. www.illinois-valley-news.com

The city's only licensed radio station is KXCJ-LP (FM 105.7), a community powered station which went on-air in December 2016.

The Cave Junction area had a pirate radio station, Hope Mountain Radio. It broadcast out of Takilma until repeated interference from government agents caused them to shut down. The station then began broadcasting legally on the internet at TakilmaFM.com, although this caused their costs to go up and necessitated fundraising activities. As of January 2007, Hope Mountain Radio broadcasts 24 hours a day with an all volunteer staff. 1

Education

Cave Junction has three schools: Illinois Valley High School, Lorna Byrne Middle School, and Evergreen Elementary School.[69] These schools are part of the Three Rivers School District, which also encompasses schools from Grants Pass and Applegate, Oregon.[70]

Two individuals linked to Illinois Valley High School (IVHS) have been inducted into regional halls of fame. In 2004, Sam Hutchins became a member of the Wild Salmon Hall of Fame for creating the non-profit Oregon Stewardship Program. Begun in 1992 to teach Illinois Valley High School students about wild steelhead in the Illinois River, by 2004 the program had been expanded to 25 schools and 1,500 students.[71] In 2007, IVHS wrestling coach Ursal "Jay" Miller was inducted into the Oregon Chapter of The National Wrestling Hall of Fame & Museum.[72]

Transportation

The Illinois Valley Airport, also known as the Siskiyou Smokejumper Base, was built by the U.S. Forest Service. It operated from 1943 to 1981 as a smokejumper base, during which time the smokejumpers parachuted on 1445 fires for 5390 fire jumps.[73] As of 2007, the airport had a fixed-base operator, aircraft rentals and instruction, hangar rentals, and a restaurant.[49]

Notable people

Cave Junction has a number of notable residents and past residents. Actor John Wayne was a visitor to a ranch in Selma, Oregon, about 10 miles (16 km) north of town. He grew fond of the area after filming Rooster Cogburn along the Rogue River. This ranch has since become the Deer Creek Center which houses the Siskiyou Field Institute.[74] Kristy Lee Cook, who was a contestant on American Idol 7, was also raised in Selma, where she used to live before joining the competition.[75] Arthur B. Robinson is the head of the Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine, which is about 7 miles (11 km) from Cave Junction.[76]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "2010 Census profiles: Oregon cities alphabetically A-C" (PDF). Portland State University Population Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- "Cavejunction.com main page". CaveJunction.com. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Short notes on the History of the Illinois River Valley Page 2". Illinois Valley Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- "Oregon Caves National Monument Timeline". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- "East Fork of the Illinois River Watershed Analysis Social Module" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- Brandt, Roger (2006-02-01). "Josephine Creek a gold nugget of county history". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06.

- McLain, Rebecca; Will Kay. "Cave Junction, Illinois Valley, Oregon" (PDF). The Sierra Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0875952772.

- Rodriguez, Bob (2007-02-14). "Bob's Corner". Illinois Valley News.

- "City of Cave Junction Transportation System Plan Adopted July 2001" (PDF). University of Oregon Scholars' Bank. July 2001. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- Fattig, Paul (2007-08-30). "Fire from the sky changed everything". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Biggest blaze in US merges with smaller Oregon fire". Planet Ark. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Salvage Logging on Big Oregon Burn Termed Radical". Environment News Service. 2004-01-12. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- Fattig, Paul (2003-07-13). "Fire danger: In a word, it's 'bad'". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- Parker, Jim (2004-08-04). "Wildfire sweeps near Cave Junction, threatens homes". KGW.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- "Cave Junction Neighborhood Profile". Yahoo Real Estate. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Current Conditions". Southern Oregon Education Service District. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- NOWData; National Weather Service Forecast Office: Medford, Oregon

- "CAVE JUNCTION 1 WNW, OR (351448)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Arts Build Communities Technical Assistance" (PDF). Oregon Arts Commission. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- "Cave Junction, Oregon". City-Data.com. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- "Josephine County Online - Sheriff's Homepage". Josephine County Online. Archived from the original on 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- "Cave Junction and The Illinois Valley". Cave Junction Chamber of Congress. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Brady, Jeff (2007-02-02). "Federal Subsidy Expires on Oregon's Timber Towns". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Mapes, Jeff (2003-11-03). "Growing its own way: Southern Oregon". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Gillespie, Danielle (2006-01-15). "Booming Winston". The News Review. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- "Josephine County Community Profile". Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Southern Oregon : Cave Junction". Passpor2Oregon.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-12. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Jorgensen, Scott (2007-09-30). "R&R biomass project awaits public hearing". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- "Great Strides Award winners - Dayton, WA; Enterprise, OR; Cave Junction, OR; and Salmon, ID". Northwest Area Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Pucci, Carol (2005-05-27). "Take a rambling, scenic drive in Southern Oregon and Northern California". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Jorgensen, Scott (2007-04-04). "Second Friday Art Walk set to resume April 13". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- "April on tap for Art Walk". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10.

- Kramer-Hover, Dorothea. "Art Walk will include 'sole-full' display". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- Pucci, Carol (2005-05-27). "Take a rambling, scenic drive in Southern Oregon and Northern California". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Kugel, Seth (2003-03-07). "Havens; Out on a Limb: Treehouses for Adults". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Welcome to Out'n'About". TreeHouses.com. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Holder, Allen (2005-04-14). "Treehouse dream comes true in Siskiyous". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- "greatcatsworldpark.com home page". Great Cats World Park. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Some folks are cat people". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10.

- "Great Cats World Park". Grantspassoregon.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Points of Interest #1". Cave Junction Chamber of Congress. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Corbin, Gary. "How beer has changed in Oregon". Guest on Tap. Archived from the original on 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- "Local Business". Local Business. Mail Tribune. 2008-01-24. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- "Rogue Valley AVA". AppellationAmerica.com. Appellation America. Archived from the original on 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- Rutan, Roger (2006-05-03). "Oregon wine pioneer made the right call in Illinois Valley". The Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- Sherman, Chris (2005-03-09). "Wine of the week Foris Fly-Over Red". St. Petersberg Times. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- "Attractions". Cave Junction Chamber of Congress. Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- Twitchell, Cleve (2005-01-12). "Fodor book gives boost to local wineries". Wine Talk. Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-07-01. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- Perdue, Andy (2003). The Northwest Wine Guide: A Buyer's Handbook. Sasquatch Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-57061-361-6.

Bridgeview Vineyards.

- "American Wine Awards 2000". American Express Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Bridgeview". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Twitchell, Cleve (2007-11-28). "Foris offers bargains for wine lovers". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- "National Register of Historic Places Listings October 26, 2001". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- "Into the wild". Illinois Valley News.

- Brandt, Roger (2006-02-22). "Legacy of hydraulic mining leaves last imprint on Illinois Valley". Illinois Valley News. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06.

- "Oregon National Register List" (PDF). Oregon.gov. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Updated status and pictures can be seen at the church's website at www

.kbcc .us - "Illinois Valley Profile". SoutherOregon.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Golfing". GrantsPassOregon.gov. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Illinois River Forks State Park". Oregon.gov. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- "Top-Rated Cave Junction Public Schools". Greatschools.net. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "Three Rivers School District - Schools". Three Rivers School District. Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Freeman, Mark (2004-10-07). "Hutchins enshrined in Wild Salmon Hall of Fame". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Here, There & Everywhere". Illinois Valley News. 2007-10-02. Archived from the original on 2007-03-06.

- "Redmond Smokejumper History". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Fattig, Paul. "John Wayne slept here". Mail Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Back home, 'Idol' Kristy Lee Cook can't have too many friends in the kitchen". International Herald Tribune. 2008-03-31. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- "Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine Overview". Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cave Junction, Oregon. |

- Entry for Cave Junction in the Oregon Blue Book

- Illinois Valley Chamber of Commerce — Cave Junction

- Factual information on Cave Junction from www.city-data.com