Island Caribs

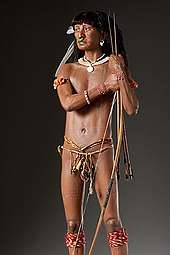

The Island Caribs, also known as the Kalinago[3] or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated language known as Island Carib.[4] They also spoke a pidgin language associated with the Mainland Caribs.[4]

Kalhíphona | |

|---|---|

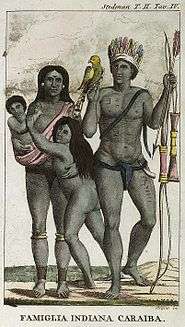

Carib family (by John Gabriel Stedman 1818) | |

| Total population | |

| 4,000[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Dominican Creole French, formerly Island Carib | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Garifuna, Black Carib, Taíno |

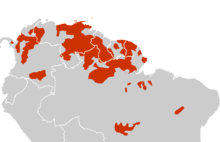

At the time of Spanish contact, the Kalinagos were one of the dominant groups in the Caribbean, which owes its name to them. They lived throughout northeastern South America, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Windward Islands, Dominica, and possibly the southern Leeward Islands. Historically, it was thought their ancestors were mainland Caribs who had conquered the islands from their previous inhabitants, the Igneri. However, linguistic and archaeological evidence contradicts the notion of a mass emigration and conquest; the Island Carib language appears not to have been Cariban, but like that of their neighbors, the Taíno. Irving Rouse and others suggest that a smaller group of mainland Caribs conquered the islands without displacing their inhabitants, eventually adopting the local language but retaining their traditions of a South American origin.[5]

In the early colonial period, the Caribs had a reputation as warriors who raided neighboring islands. According to the Spanish conquistadors, the Carib Indians were cannibals who regularly ate roasted human flesh.[6] However, there are debates as to whether they were cannibals. Some claim there is evidence as to the taking of human trophies and the ritual cannibalism of war captives among both Carib and other Amerindian groups such as the Arawak and Tupinamba. Others argue Europeans misunderstood rituals, or falsely portrayed them to justify conquest and genocide. Today, the Caribs and their descendants continue to live in the Antilles, notably on the island of Dominica. The Garifuna or "Black Caribs", a group of mixed Carib, Arawak and African ancestry, also live principally in Central America.

History

The Caribs are believed to have migrated from the Orinoco River area in South America to settle in the Caribbean islands about 1200 AD, according to carbon dating . Over the two centuries leading up to Christopher Columbus' arrival in the Caribbean archipelago in 1492, the Caribs mostly displaced the Maipurean-speaking Taínos by warfare, extermination, and assimilation. The Taíno had settled the island chains earlier in history, migrating from the mainland.[7]

Caribs traded with the Eastern Taíno of the Caribbean Islands.

The Caribs produced the silver products which Ponce de Leon found in Taíno communities. None of the insular Amerindians mined for gold but obtained it by trade from the mainland. The Caribs were skilled boat builders and sailors. They appeared to have owed their dominance in the Caribbean basin to their mastery of warfare.

According to Floyd, "The question arose in Columbus's time whether Indians could be enslaved and Queen Isabel had ruled against it. At about the same time, however, Ojeda, Bastidas, and other explorers voyaging along the Spanish Main had been attacked by Indians with poisoned arrows - all such Indians were considered Caribs - which took a considerable toll of Spanish lives. These attacks and the evidence some of the perpetrators, at least, were cannibals, provided the rationale for the decree authorizing enslavement of Caribs." On 3 June 1511, king Ferdinand declared war on the Caribs.[8] Island Caribs nevertheless mostly succeeded in keeping their islands unoccupied by Spaniards.

In the 17th century, Island Caribs were displaced with a great loss of life by a new wave of European invaders: French and English. Most fatalities resulted from Eurasian infectious diseases such as smallpox, which they had no natural immunity to, as well as warfare.

In 1660, France and England signed with Island Caribs the Treaty of Saint Charles that stipulated that Caribs would evacuate all the Lesser Antilles except for Dominica and Saint Vincent, which were recognised as reserves. However, the English would later ignore the treaty and ended up annexing both islands in 1763.[9] To this date, a small population of around 3,000 Caribs survives in the Carib Territory in northeast Dominica. Chief Kairouane and his men from Grenada jumped off of the “Leapers Hill" rather than face slavery under the French invaders and have served as an iconic representation of the Carib spirit of resistance.[10][11][12]

The 'Black Caribs' (later known as carifuna) of St. Vincent (St. Vincent has some "Yellow Caribs" as well) were descended from a group of enslaved Africans who were marooned from shipwrecks of slave ships, as well as slaves who escaped here. They intermarried with the Carib and formed the last native culture to resist the British. It was not until 1795 that British colonists deported the Black Caribs to Roatan Island, off Honduras. Their descendants continue to live there today and are known as the Garifuna ethnic group. Carib resistance delayed the settlement of Dominica by Europeans. The Black Carib communities that remained in St. Vincent and Dominica retained a degree of autonomy well into the 19th century.

People

The Kalinago of Dominica maintained their independence for many years by taking advantage of the island's rugged terrain. The island's east coast includes a 3,700-acre (15 km2) territory formerly known as the Carib Territory that was granted to the people by the British Crown in 1903. There are only 3,000 Caribs remaining in Dominica. They elect their own chief. In July 2003, the Kalinago observed 100 Years of Territory. In July 2014, Charles Williams was elected Kalinago Chief,[14] who succeeded Chief Garnette Joseph.

Several hundred Carib descendants live in the U. S. Virgin Islands, St. Kitts & Nevis, Antigua & Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Trinidad and St. Vincent. "Black Caribs," the descendants of the mixture of Africans live in St. Vincent whose total population is unknown. Some ethnic Carib communities remain on the American mainland, in countries such as Guyana and Suriname in South America, and Belize in Central America. The size of these communities varies widely.

During the beginning of 20th century, the Island Carib population in St. Vincent was greater than the one in Dominica. Both the Island Caribs (Yellow Caribs) and the Black Caribs (Garifuna) fought against the British during the Second Carib War. However, the British deported only the Garifuna (entire population of 4,338, of which around 55% died of Yellow fever), while the Island Caribs were allowed to stay (102 in total, of which only 80 survived the war)[15]. The 1812 eruption of La Soufrière destroyed the Carib territory killing a majority of the Yellow Caribs. After the eruption 130 Yellow Caribs and 59 Black Carbis survived on St. Vincent. Unable to recover from the damage caused by the eruption, 120 of the Yellow Caribs under Captain Baptiste emigrated to Trinidad. In 1830, the Carib population numbered less than 100[16][17]. The population made a remarkable recovery after that, although almost the entire tribe died out during the 1902 eruption of La Soufrière.

Religion

The Caribs are believed to have practiced polytheism. As the Spanish began to colonise the Caribbean area, they wanted to convert the natives to Catholicism.[18] The Caribs destroyed a church of Franciscans in Aguada, Puerto Rico and killed five of its members, in 1579.[19]

Currently, the remaining Kalinago in Dominica practice parts of Catholicism through baptism of children. However, not all practice Christianity. Some Caribs worship their ancestors and believe them to have magical power over their crops. One strong religious belief Caribs possess is that Creoles practice dangerous witchcraft.[20] Creole people are Caribs mixed with those who settled the island. An example of said people are Haitian Creoles, who speak a mix of French and the native Carib language. Many Caribs dislike the impurities that are perceived to be present in the Creole population.[21]

Music

Garifuna music from the Garifuna people, the descendants of Caribs, Arawak and West African people, is quite different from the music in the rest of Central America. The most famous form is punta. Its associated musical style, which has the dancers move their hips in a circular motion. An evolved form of traditional music, still usually played using traditional instruments, punta has seen some modernization and electrification in the 1970s; this is called punta rock. Traditional punta dancing is consciously competitive. Artists like Pen Cayetano helped innovate modern punta rock by adding guitars to the traditional music, and paved the way for later artists like Andy Palacio, Children of the Most High and Black Coral. Punta was popular across the region, especially in Belize, by the mid-1980s, culminating in the release of Punta Rockers in 1987, a compilation featuring many of the genre's biggest stars.

Other forms of Garifuna music and dance include: hungu-hungu, combination, wanaragua, abaimahani, matamuerte, laremuna wadaguman, gunjai, sambai, charikanari, eremuna egi, paranda, berusu, punta rock, teremuna ligilisi, arumahani, and Mali-amalihani. Punta is the most popular dance in Garifuna culture. It is performed around holidays and at parties and other social events. Punta lyrics are usually composed by the women. Chumba and hunguhungu are a circular dance in a three-beat rhythm, which is often combined with punta. There are other songs typical to each gender, women having eremwu eu and abaimajani, rhythmic a cappella songs, and laremuna wadaguman, men's work songs, chumba and hunguhungu, a circular dance in a three-beat rhythm, which is often combined with punta.

Drums play a very important role in Garifuna music. There are primarily two types of drums used: the primero (tenor drum) and the segunda (bass drum). These drums are typically made of hollowed-out hardwood such as mahogany or mayflower, with the skins coming from the peccary (wild bush pig), deer, or sheep.

Also used in combination with the drums are the sisera. These shakers are made from the dried fruit of the gourd tree, filled with seeds, then fitted with hardwood handles.

Paranda music developed soon after the Garifunas arrival in Central America. The music is instrumental and percussion-based. The music was barely recorded until the 1990s, when Ivan Duran of Stonetree Records began the Paranda Project.

In contemporary Belize there has been a resurgence of Garifuna music, popularized by musicians such as Andy Palacio, Mohobub Flores, & Adrian Martinez. These musicians have taken many aspects from traditional Garifuna music forms and fused them with more modern sounds. Described as a mixture of punta rock and paranda. One great example is Andy Palacio's album Watina, and Umalali: The Garifuna Women's Project, both released on the Belizean record label Stonetree Records.

In the Garifuna culture, there is another dance called Dugu. This dance is a ritual done for a death in the family to pay their respect to their loved ones. In 2001, Garifuna music was proclaimed one of the masterpieces of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity by UNESCO.

Ancestral honor

The Island Carib word karibna meant "person". It became the origin of the English "cannibal".[22] Although, among the Caribs, it was apparently associated with rituals related to the eating of war enemies. There is evidence as to the taking of human trophies and the ritual cannibalism of war captives among both Arawak and other Amerindian groups such as the Carib and Tupinamba.[23]

The Caribs had a tradition of keeping bones of their ancestors in their houses. Missionaries, such as Père Jean Baptiste Labat and Cesar de Rochefort, described the practice as part of a belief that the ancestral spirits would always look after the bones and protect their descendants. The Caribs have been described as vicious and violent people in the history of the people who battled against other tribes. Rochefort stated they did not practice cannibalism.[24]

Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano was killed and said to have been eaten by Carib natives on what is now Guadeloupe (French West Indies) in 1528 (before called Karukera by the Amerindian people which means “the island of beautiful waters”), during his third voyage to North America, after exploring Florida, the Bahamas and the Lesser Antilles. Historian William Riviere[25] has described most of the cannibalism as related to war rituals.

Medicine

The Kalinago is somewhat known for their extensive use of herbs for medicinal practices. Today, a combination of bush medicine and modern medicine is used by the Caribs of Dominica. For example, various fruits and leaves are used to heal common ailments. For a sprain, oils from coconuts, snakes, and bay leaves are used to heal the injury. In Carib history, a more extensive use of plant and animal products were used for medicine, but with modernization and discovery of more effective and safe techniques, more Caribs are seen using local hospitals today.[26]

Kalinago canoe project

In 1997 Dominica Carib artist Jacob Frederick and Tortola artist Aragorn Dick Read joined forces and set out to build a traditional canoe based on the fishing canoes still used in Dominica, Guadeloupe and Martinique. The project consisted of a return voyage by canoe to the Orinoco delta to meet up with the Kalinago tribes still living in those parts. On the way a cultural assessment was carried out and ties were reestablished with the remaining communities along the island chain. A documentary, The Quest of the Carib Canoe, was made by the BBC.[27] The expedition sent shock waves through the Lesser Antilles as it made the local governments aware of the presence and the struggles for cultural survival of the Kalinago.

See also

- Carib Expulsion

- Carib language

- Cariban languages

- Kalinago Genocide of 1626

- Santa Rosa Carib Community

References

- "About Us". Archived from the original on 2017-09-16. Retrieved 2017-07-02. "Presently approximately 3,000 Kalinagos live in a collectively owned 3,700 acre territory, spread over eight hamlets, on the north-eastern coast of Dominica."

- "Central America :: Saint Vincent and the Grenadines - The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. 2018-12-27. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- "Change from Carib to Kalinago now official". 2015-02-22. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2016-03-03., "Change from Carib to Kalinago now official", Dominica News Online

- Haurholm-Larsen, Steffen (2016). A Grammar Of Garifuna. University of Bern. pp. 7, 8, 9.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

Island Carib.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- Sweeney, James L. (2007). "Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent" Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, African Diaspora Archaeology Network, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, March 2007, retrieved 26 April 2007

- Floyd, Troy (1973). The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492-1526. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 133–135.

- Delpuech, André (2001). Guadeloupe amérindienne. Paris: Monum, éditions du patrimoine. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9782858223671. OCLC 48617879.

- Newton, Melanie J. (2014). "Genocide, Narrative, And Indigenous Exile From the Caribbean Archipelago". Caribbean Quarterly. 60 (2): 5. doi:10.1080/00086495.2014.11671886.

- Crouse, Nellis Maynard (1940). French pioneers in the West Indies, 1624-1664. New York: Columbia university press. p. 196.

- Margry, Pierre (1878). "Origines Francaises des Pays D'outre-mer, Les seigneurs de la Martinique". La Revue maritime: 287–8.

- Ostler, Nicholas (2005). Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. p. 362.

- "Kalinago People | | a virtual Dominica". Archived from the original on October 26, 2010.

- Gargallo, Francesca (August 4, 2002). "Garífuna, Garínagu, Caribe: historia de una nación libertaria". Siglo XXI – via Google Books.

- Taylor, Chris (May 3, 2012). "The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival, and the Making of the Garifuna". Univ. Press of Mississippi – via Google Books.

- Stanton, William (August 4, 2003). "The Rapid Growth of Human Populations, 1750-2000: Histories, Consequences, Issues, Nation by Nation". multi-science publishing – via Google Books.

- Menhinick, Kevin, "The Caribs in Dominica" Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Copyright © Delphis Ltd. 1997–2011.

- Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 238. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Carib, Island Carib, Kalinago People (Anthropology)". Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- "Haitian Creole". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Harper, Douglas. "Cannibal". Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Whitehead, Neil L. (20 March 1984). "Carib cannibalism. The historical evidence". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 70 (1): 69–87. doi:10.3406/jsa.1984.2239.

- Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 22. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Historical Notes on Carib Territory Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, William (Para) Riviere, PhD, Historian

- Regan, Seann. "Healthcare Use Patterns in Dominica: Ethnomedical Integration in an Era of Biomedicine".

- "Quest of the Carib Canoe". Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

Further reading

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, The Traveller's Tree, 1950, pp. 214–5

Resources

- Allaire, Louis (1997). "The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles", in Samuel M. Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, pp. 180–185. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1531-6.

- Steele, Beverley A. (2003). Grenada, A history of its people, New York: Macmillan Education, pp. 11–47

- Honeychurch, Lennox, The Dominica Story, MacMillan Education, 1995.

- Davis, D and Goodwin R.C. "Island Carib Origins: Evidence and non-evidence", American Antiquity, vol.55 no.1(1990).

- Eaden, John, The Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693–1705, Frank Cass, 1970.

- "Carib", Ethnologue

- "Kalinago", Name change announcement of November 15, 2010, by the Office of the Kalinago Council posted at Dominica News Online

- (in French) Brard, R., Le dernier Caraïbe, Bordeaux : chez les principaux libraires, 1849, Manioc : Livres anciens | L E dernier caraïbe. Bordeaux.

- Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 22. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caribs. |