Carburetor heat

Carburetor, carburettor, carburator, carburettor heat (usually abbreviated to 'carb heat') is a system used in automobile and piston-powered light aircraft engines to prevent or clear carburetor icing. It consists of a moveable flap which draws hot air into the engine intake. The air is drawn from the heat stove, a metal plate around the (very hot) exhaust manifold.

Operation

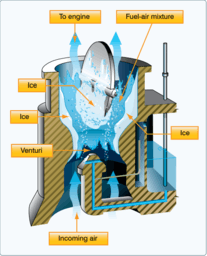

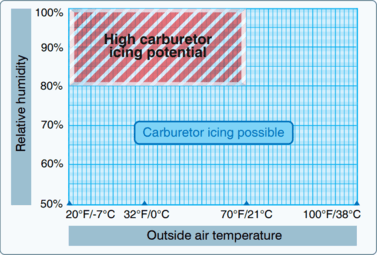

Carburetor icing is caused by the temperature drop in the carburetor, as an effect of fuel vaporization, and the temperature drop associated with the pressure drop in the venturi. If the temperature drops below freezing, water vapor will freeze onto the throttle valve, and other internal surfaces of the carburetor. The venturi effect can drop the ambient air temperature by 70 absolute degrees Fahrenheit (F), or 38.89 absolute degrees Celsius (C). In other words, air at an outside temperature of 100 degree F, can drop to 30 degrees F in the carburetor. Carburetor icing most often occurs when the outside air temperature is below 70 degrees F (21 degrees C) and the relative humidity is above 80 percent.[1]

Carburetor heat uses hot air drawn from the heat exchanger or heat stove (a metal plate around the exhaust manifold) to raise the temperature in the venturi section high enough to prevent or remove any ice buildup. Because hot air is less dense than cold air, engine power will drop when carburetor heat is used.

Engines equipped with fuel injection do not require carb heat as they are not as prone to icing - the gasoline is injected as a steady stream just upstream of the intake valve, so evaporation occurs as the fuel/air mixture is being drawn into the cylinder, where metal temperatures are higher. The exception is monopoint or TBI injection systems which spray fuel onto the throttle plate.

Some multipoint injection engines route engine coolant through the throttle body to prevent ice buildup during prolonged idling. This prevents ice from forming around the throttle plate but does not draw large amounts of hot air into the engine as carburetor heat does.

In aircraft

A fixed-pitch propeller aircraft will show a decrease in engine RPM, and perhaps run rough, when carburetor ice has formed. However, a constant-speed propeller aircraft will show a decrease in manifold pressure as power is reduced.[1]

In light aircraft, the carburetor heat is usually manually controlled by the pilot. The diversion of warm air into the intake reduces the available power from the engine for three reasons: thermodynamic efficiency is slightly reduced, since it is a function of the difference in temperature between the incoming and exhaust gases; the quantity of air available for combustion inside the cylinders is reduced due to the lower density of the warm air; and the previously-correct ratio of fuel to air is upset by the lower-density air, so some of the fuel will not be burned and will exit as unburned hydrocarbons.

Thus the application of carb heat is manifested as a reduction in engine power, up to 15 percent. If ice has built up, there will then be a gradual increase in power as the air passage is freed up by the melting ice. The amount of power regained is an indication of the severity of ice buildup.[1]

It must be kept in mind that the ingestion of small amounts of water into the engine following melting in the carburetor may cause an initial period of rough running for as much as one or two minutes before the power increase is noted. Again, the pilot will note this as evidence that icing conditions are present. However, more than one pilot, when confronted with a rough running engine has mistakenly turned the carburetor heat back off, thereby exacerbating the situation.

Applying carb heat as a matter of routine is built into numerous in-flight and pre-landing checks (e.g. see BUMPH and GUMPS). In long descents, carb heat may be used continuously to prevent icing buildup; with the throttle closed there is a large pressure (and therefore temperature) drop in the carburetor which can cause rapid ice buildup that could go unnoticed because engine power is not used. In addition, the exhaust manifold cools considerably when power is removed, so if carb icing occurs there may not be heat sufficient to remove it. Thus most operational checklists call for the routine application of carb heat whenever the throttle is closed in flight.

Usually, the air filter is bypassed when carb heat is used. If the air filter becomes clogged (with snow, ice, or dust debris), using carb heat allows the engine to keep running. Because using unfiltered air can cause engine wear, carb heat usage on the ground (where dusty air is most probable) is kept to a minimum.

Altitude has an indirect effect on carburetor ice because there are usually significant temperature differences with altitude. Clouds contain moisture, and therefore flying through clouds may necessitate more frequent use of carb heat.

The intake air of an aircraft engine equipped with a supercharger is heated through compression, so the air entering the throttle body is already warmed enough that carb heat is unnecessary.

In automobiles

In cars, carburetor heat may be controlled automatically (e.g. by a wax-pellet driven flap in the air intake) or manually (often by rotating the air cleaner cover between 'summer' and 'winter' settings), with use both of "heat stove" type systems, and electric-filament booster elements directly attached to the carb or TBI module. The air filter bypass found on aircraft engines is not used, because the air filter on automobiles is not normally exposed to the elements (and an automobile drives around at low altitudes, and has to share dusty, grimy roads with other cars, so it is much more prone to ingesting dust and grit when running without a filter than an aircraft is) - at least, not so much to allow an obstructive build-up of snow and/or ice upon it - and because it is usually mounted closer to the cylinder block, such that it is able to absorb enough engine heat to keep itself from freezing up (airflow through the generally large-aperture filter is slower than through the throttle body itself, and thus less influenced by cooling effects). However, this is not always sufficient, and some automobiles have a history of temporary engine failure during rain or snow conditions (power output drops below that sufficient to continue propelling the vehicle, or even to prevent stalling whilst unladen, and the car cannot be driven/engine restarted until it has stood awhile without a mass quantity of cold, wet air travelling through it, so that the residual engine heat can melt the accumulated ice).

Automobile engines may also use a heat riser, which heats the air/fuel mixture after it has left the carburetor; this is a low temperature fuel economy and driveability feature with most benefits seen at low rpms.

Motorcycle engines may also use carburetor heating. In many cases, and especially with simple air-cooled engines, this relies solely upon an electric heating element attached to the carburetor, as a heat stove and attached warm air feed would be bulky, complex, difficult to route, and may even interfere with normal cooling of the cylinder block. On a few of their air cooled motorcycles, Ducati have utilized an oil line to warm the base of the carb which is operated by the rider via a small valve.

See also

References

- Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, FAA-H-8083-25B (PDF). US Dept. of Transportation, FAA. 2016. pp. 7-8–7-10.

External links

- Picture of automobile engine exhaust manifold heat stove. http://www.widnerindustries.com/product4.htm