Battle of Schellenberg

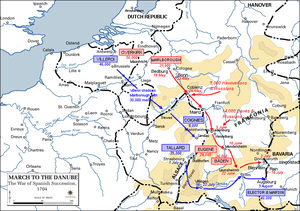

The Battle of Schellenberg, also known as the Battle of Donauwörth, was fought on 2 July 1704[lower-alpha 1] during the War of the Spanish Succession. The engagement was part of the Duke of Marlborough's campaign to save the Habsburg capital of Vienna from a threatened advance by King Louis XIV's Franco-Bavarian forces ranged in southern Germany. Marlborough had commenced his 250-mile (400 km) march from Bedburg, near Cologne, on 19 May; within five weeks he had linked his forces with those of the Margrave of Baden, before continuing on to the river Danube. Once in southern Germany, the Allies' task was to induce Max Emanuel, the Elector of Bavaria, to abandon his allegiance to Louis XIV and rejoin the Grand Alliance; but to force the issue, the Allies first needed to secure a fortified bridgehead and magazine on the Danube, through which their supplies could cross to the south of the river into the heart of the Elector's lands. For this purpose, Marlborough selected the town of Donauwörth.

| Battle of Schellenberg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

Assault on Schellenberg. Tapestry detail by Judocus de Vos | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Once the Elector and his co-commander, Marshal Marsin, knew of the Allies' objective, they dispatched Count d'Arco with an advance force of 12,000 men from their main camp at Dillingen to strengthen and hold the Schellenberg heights above the town. Rejecting a protracted siege, Marlborough decided in favour of a quick assault, before the position could be made impregnable. After two failed attempts to storm the barricades, the Allied commanders, acting in unison, finally managed to overwhelm the defenders. It had taken just two hours to secure the bridgehead over the river in a hard-fought contest, but following the victory, momentum was lost to indecision. The deliberate devastation of the Elector's lands in Bavaria failed to bring Max Emanuel to battle or persuade him back into the Imperial fold. Only when Marshal Tallard arrived with reinforcements to strengthen the Elector's forces, and Prince Eugene of Savoy arrived from the Rhine to bolster the Allies, was the stage finally set for the decisive action at the Battle of Blenheim the following month.

Background

The Battle of Schellenberg was part of the Grand Alliance's campaign of 1704 to prevent the Franco-Bavarian army from threatening Vienna, the capital of Habsburg Austria. The campaign began in earnest on 19 May when the Duke of Marlborough began his 250-mile (400 km) march from Bedburg near Cologne towards the Elector of Bavaria's and Marshal Marsin's Franco-Bavarian army on the Danube. Marlborough had initially deceived the French commanders – Marshal Villeroi in the Spanish Netherlands and Marshal Tallard along the Rhine – into thinking his target was Alsace or the Moselle farther to the north. However, when the Elector was notified on 5 June of Marlborough's march from the Low Countries, he had correctly predicted that it was his principality of Bavaria that was the Allies' real target.[4]

Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I was keen to lure the Elector back into the Imperial fold after he had switched allegiance to fight for King Louis XIV before the war. Given this duplicity, Marlborough thought the best way to secure Bavaria for the Alliance was to negotiate from a position of strength by invading the Elector's territories, hoping to persuade him to change sides before he could be reinforced.[5] By 22 June Marlborough's army had linked up with elements of the Margrave of Baden's Imperial forces at Launsheim; by the end of June their combined strength totalled nearly 80,000 men (see map on right). The Franco-Bavarian army camped at Ulm were numerically inferior to the Allies, and a large part of the Elector's troops were scattered about garrisons in his territories as far as Munich and the Tyrolese frontier, but his position was far from desperate: if he could hold out for a month, Tallard would arrive from the Rhine with French reinforcements.[6]

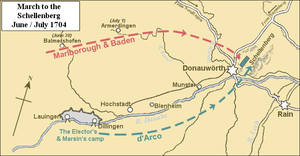

Once the Allies had combined their forces, the Elector and Marsin moved their 40,000 troops into the entrenched camp between Dillingen and Lauingen on the north bank of the Danube. The Allied commanders – unwilling to attack such a strong position rendered impregnable by redoubts and inundations – passed round Dillingen to the north through Balmershofen and Armerdingen in the direction of Donauwörth.[6] If captured, the bridgehead at Donauwörth (overlooked by the Schellenberg) would offer new communications with the friendly states in central Germany by way of Nördlingen and Nuremberg, as well as providing a good crossing-place over the Danube for re-supply when the Allies were south of the river.

Prelude

Schellenberg's defences

The Schellenberg heights dominate the skyline to the northeast of Donauwörth – the walled town on the confluence of the Wörnitz and Danube rivers. With one flank of the hill protected by dense, impenetrable trees of the Boschberg wood, and the river Wörnitz and marshes protecting its southern and western quarters, the Schellenberg heights offer a commanding position for any defender. However, its oval shaped summit was flat and open, and its 70-year-old defences, including an old fort built by the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus during the Thirty Years' War, were neglected and in a dilapidated state. When the unexpected attack took place the bastions, the curtain, and the ditch were fairly complete along the long eastern face from the shore of the Danube to the wooded hilltop, but in the shorter section from the wood to the fort – the angle where Marlborough's attack was delivered – the earthwork had been more hastily made up of fascines of brushwood thinly covered with soil. The western section of the lines ran steeply downhill from the fort to the city walls. Here, there was little to show in terms of defences, but to compensate the line could be protected by a flanking fire from the town.[7] (See 'Schellenberg' map below.)

In 1703 Marshal Villars had advised the Elector to fortify his towns, "... and above all the Schellenberg, that fort above Donauwörth, the importance of which the great Gustavus taught us."[8] The Elector, whose relationship with Villars had since collapsed, had initially ignored the advice to repair the decaying defences, but once it was realised that Donauwörth was to be attacked, Count d'Arco, a Piedmontese officer, was despatched from the camp at Dillingen with orders to strengthen and hold the position. D'Arco was entrusted with 12,000 men, most of whom were drawn from Bavaria's best units including the Elector's Guards and the regiment of the Prince Electoral, led by veteran officers.[5] In total, the garrison defending the Schellenberg consisted of 16 Bavarian and seven French infantry battalions, six squadrons of French and three squadrons of Bavarian dragoons, supported by 16 guns. In addition, Donauwörth was held by a French battalion and two battalions of Bavarian militia.[9]

Initial manoeuvres

On the night of 1–2 July, the Allies were camped at Armerdingen, 15 miles (24 km) from Donauwörth. It was here when Marlborough received an urgent message from Baron Moltenburg, Prince Eugene's Adjutant-General, that Marshal Tallard was marching with 35,000 troops through the Black Forest to reinforce the Franco-Bavarian army. This news convinced Marlborough that he did not have time for a protracted siege and, despite protestations from Baden – arguing that a direct assault would incur severe casualties – the Duke planned for an outright assault on the position.[1] D'Arco knew of the whereabouts of the Allied camp at Armerdingen, and was confident he had at least a full day and night to prepare his defences.

At 03:00 on 2 July the Allied advance guard began to break camp for the march towards Donauwörth and the Schellenberg heights.[10] Marlborough personally oversaw the advance of the initial assault force of 5,850 foot, drawn up in groups of approximately 130 men from each battalion under his command.[1] The Dutch General Johan Wijnand van Goor would lead this vanguard. Behind these stormers came 12,000 Allied infantry in two echelons, each of eight battalions (English, Dutch, Hanoverian and Hessian) under Major General Henry Withers and Count Horn, supported by Henry Lumley's and Graf Reynard van Hompesch's 35 squadrons of British and Dutch cavalry and dragoons. Baden, whose wing of the army marched behind Marlborough's, would hold a brigade of Imperial grenadiers ready for action when the opportunity came as there was insufficient room in front of the Schellenberg for them to fully deploy. In all, the Allies were deploying 22,000 men in the operation.[1]

Riding far ahead of the army Marlborough personally examined the enemy position, observing through his telescope preparations for a camp on the far side of the river in expectation of the arrival of the Elector's main force the following day.[11] There was, therefore, no time to be lost. Although the Duke had 12 hours of light remaining in the day his men were still struggling in the mud, miles away behind the river Wörnitz, and they could not hope to launch the attack before about 18:00, leaving just two hours before nightfall.[12] As the Allies marched, work on the defences of Donauwörth and the Schellenberg were proceeding in earnest. With the aid of French engineer officers d'Arco started to repair and strengthen the two miles (3.2 km) of old entrenchments that connected the fort of Gustavus with the Danube on one side, and the town walls on the other. A French commander in Bavarian service and chronicler of the period, Colonel Jean Martin de la Colonie, later wrote – "The time left to us was too short to complete this satisfactorily."[13]

The Allied cavalry began to appear at about 08:00, five miles (8 km) or six miles (9.7 km) away on d'Arco's left front to the north-west, followed by the infantry. By 10:00 Marlborough's Quartermaster-General, William Cadogan, began to mark out land for an encampment within sight of the Schellenberg – short of the Wörnitz – to give the impression they were intending a leisurely siege.[14] Count d'Arco watched Cadogan's preparations and, falling for the deception, left the supervision of the still incomplete defences to lunch with the French commander of Donauwörth, Colonel DuBordet, safe in the belief that he had the rest of the day and night to finish the defences.[15] However, the columns marched purposefully onwards, and by mid-afternoon they had crossed the river Wörnitz at Ebermorgen, intent on launching an immediate assault. The Allies were spotted by the Bavarian outposts who, after setting fire to Berg and surrounding hamlets, rushed off to sound the alarm. General d'Arco, rudely interrupted from his lunch, rushed up the Schellenberg and called his men to arms.[16]

Battle

Marlborough's first assault

.jpg)

Although Marlborough knew a frontal attack on the Schellenberg would be costly, he was convinced that it was the only way of securing the speedy capture of the town: unless he captured the summit by nightfall, it would never be taken – the defences would be too strong, and the main Franco-Bavarian army, which was hastening from Dillingen towards Donauwörth, would arrive to defend the position.[11] A female dragoon, Christian Welsh (she had disguised her true sex) remembered, "Our vanguard did not come into sight of the enemy entrenchments til the afternoon; however, not to give the Bavarians time to make themselves yet stronger, the duke ordered the Dutch General Goor ... to attack as soon as possible."[17] At about 17:00, as a preliminary to the attack, Marlborough's artillery commander, Colonel Holcroft Blood, pounded the enemy from a position near Berg; each salvo was countered by d'Arco's guns from Gustavus's fort and from just outside the Boschberg wood.

General d'Arco now ordered de la Colonie's French grenadiers into reserve on top of the Heights (above the breastworks manned by the Bavarians), ready to plug any gaps in their defences at the appropriate time. However, due to the flatness of the summit this position offered his men limited protection from the Allied guns. This exposure was noted by Colonel Blood who, sighting his artillery upon the summit, was able to inflict serious casualties upon de la Colonie's men.[19] De la Colonie later recorded – "They concentrated their fire upon us, and with their first discharge carried off Count de la Bastide ... so that my coat was covered with brains and blood."[20] Notwithstanding this barrage, and despite losing five officers and 80 grenadiers before firing a shot, de la Colonie insisted his French regiment stayed at their post, determined as he was to maintain discipline and ensure his troops would be in good order when called into action.[21]

There was just enough time before nightfall to storm the position on its north side (mainly up the steepest part of the slope immediately north of Gustavus's fort), but not enough time to develop simultaneous attacks from other sides.[22] The attack went in around 18:00, led by the advanced guard of the 'forlorn hope'. This force of 80 English grenadiers from the 1st English Foot Guards, led by Viscount Mordaunt and Colonel Richard Munden, was designed to draw the enemy fire and thus enable the Allied commanders to discern the defensive strong points.[23] The main force followed closely behind. "The rapidity of their movements, together with their loud yells, were truly alarming", recalled la Colonie, who, in order to drown out the shouts and hurrahs, ordered his drummer to beat charge "so as to drown them with their noise, lest they should have a bad effect upon our people."[24]

As the range closed the Allies became easy targets for the Franco-Bavarian musket- and grape-shot; the confusion exacerbated by fizzing hand-grenades thrown down the slope by the defenders.[25] To aid their assault, each Allied soldier carried a bundle of fascines (earlier cut from the Boschberg wood), with which to bridge the ditches in front of the breastworks to speed their passage. However, the fascines were mistakenly thrown into a dry gully – formed by the recent summer rains – instead of the Bavarians' defensive trench about 45 m (50 yards) farther on.[25] Nevertheless, the Allies continued to push forward, joining battle with the Bavarians in savage hand-to-hand fighting. Behind the defences the Elector's Guards and la Colonie's men bore the brunt of the attack so that, "The little parapet which separates the two forces became the scene of the bloodiest struggle that could be conceived."[24] But the assault failed to penetrate the defences, and the Allies were forced to fall back to their lines. General Johan Wijnand van Goor, a favourite of Marlborough who had led the attack, numbered among the Allied fatalities.

Marlborough's second assault

The second assault proved no more successful. The red-coated English and the blue-coated Dutch advanced side by side in perfect order for a second attempt. Requiring from them another concerted effort their general officers personally led the men from the front into a second torrent of musket-shot and grenades.[26] Again the Allies left many dead and wounded at the enemy palisade including Marshal Count von Limburg Styrum who had led the second assault. With broken ranks, and in confusion, the attacking troops fell once more back down the hill. With the Allies repulsed for a second time the exultant Bavarian grenadiers, with bayonets fixed, poured over their breastworks to pursue the attackers and drive them to defeat.[27] But English guardsmen, aided by Lumley's dismounted cavalrymen, prevented a total rout, compelling the Bavarians back behind their defences.[28]

Baden's assault

At this moment, having failed twice to make a breakthrough, Marlborough received intelligence that the defences linking the town walls with the breastwork on the hill were now sparsely manned (Marlborough's unsuccessful attacks had drawn d'Arco's men away from other parts of the stronghold, leaving his left flank almost defenceless and highly vulnerable).[29] The other Allied commander, the Margrave of Baden (who had entered the battle half an hour after Marlborough), also noticed this opportunity and was soon hurrying with his grenadiers from the hamlet of Berg, and across the Kaibach stream to assault the position.[30]

Critically, Donauwörth's garrison commander had withdrawn his men inside the town, locked the gates, and could now only offer scattered shots from its walls.[31] Baden's Imperial troops (now supported by eight of Marlborough's reserve battalions), easily breached these weakened defences, defeated the two battalions of infantry and a handful of cavalry still defending the area, and were able to form up at the foot of the Schellenberg, interposing themselves between d'Arco and the town.[lower-alpha 3] Noticing the danger d'Arco hurried to the rear to summon his dismounted French dragoons (held back in the lee of the hill) in an attempt to stem the advancing Imperialists marching up the glacis.[30] However, three companies of Baden's grenadiers confronted them with concentrated volleys, forcing the cavalry to retire. This action subsequently left d'Arco out of position and out of contact with his main force fiercely resisting on the crest of the hill. The Franco-Bavarian commander headed for the town and, according to de la Colonie – "... had some difficulty in entering owing to the hesitation of the commandant to open the gates."[32]

Breakthrough

Aware that Imperial troops had breached the Schellenberg's defences Marlborough launched a third assault. This time the attackers formed a broader front, requiring d'Arco's men to spread their fire, thus reducing the deadly effectiveness of their musketry and grenades. But the defenders, including la Colonie, (unaware that the Imperialists had penetrated their left flank, and that d'Arco had retreated to Donauwörth),[33] were still confident in their ability to repel the enemy – "We remained steady at our post; our fire was regular as ever, and kept our opponents in check."[32] It was not long, however, before the Franco-Bavarian forces fighting on the hill became conscious of Baden's infantry approaching from the direction of the town. Many of the officers, including de la Colonie, initially thought that the advancing troops were reinforcements from DuBordet's garrison in Donauwörth, but it soon became apparent that they were in fact Baden's troops.[30] "They [Baden's Imperial grenadiers] arrived within gunshot of our flank about 7:30 in the evening, without our being aware of the possibility of such a thing." Wrote de la Colonie. "So occupied were we in defence of our own particular post ..." After establishing themselves at the summit of the Heights on the Allied right, Baden's men now fired upon the surprised defenders of the Schellenberg, compelling them to re-align in order to meet this unexpected threat. Consequently, Marlborough's assaulting troops on the Allied left, supported by a fresh echelon of dismounted English dragoons, were able to scramble over the now weakly defended breastwork and push the defenders back to the crown of the hill. The enemy at last fell into confusion.[34]

The outnumbered defenders of the Schellenberg had resisted the Allied assaults for two hours, but now under pressure from both Baden's and Marlborough's forces, their stalwart defence was over. As panic spread through the Franco-Bavarian army, Marlborough unleashed 35 squadrons of cavalry and dragoons to pursue the fleeing troops, ruthlessly cutting down the enemy soldiers to the shouts of "Kill, kill and destroy!"[35] There was no easy escape route. A pontoon bridge over the Danube had collapsed under their weight, and many of d'Arco's troops, most of whom could not swim, drowned trying to cross the fast-flowing river.[36] Many others who had been cut off on the northern shore of the Danube ran for their lives amongst the reed-beds, vainly endeavouring to avoid the Allied sabres. Others headed for the village of Zirgesheim, straining to escape to the wooded hills beyond. Only to the west could Marlborough detect a few Franco-Bavarian battalions crossing the Danube by Donauwörth's bridge in tolerable order, before darkness descended over the battlefield.[37]

Aftermath

De la Colonie was one of the few to escape, but the Elector of Bavaria had lost many of his best troops which was to have a profound effect on the ability of the Franco-Bavarian forces to face the Allies in the rest of the campaign.[36] Very few of the men who had defended the Schellenberg rejoined the Elector's and Marsin's army.[38] Included amongst this number, however, were the Comte d'Arco and his second-in-command, the Marquis de Maffei, both of whom later defended Lutzingen at the Battle of Blenheim. Of the 22,000 Allied troops engaged, over 5,000 had become casualties, overwhelming the hospitals that Marlborough had set up in Nördlingen.[39] Amongst the Allied fatalities were six lieutenant-generals, four major-generals, and 28 brigadiers, colonels and lieutenant-colonels, reflecting the exposed positions of senior officers as they led their men forward in the assaults.[40] No other action in the War of the Spanish Succession claimed so many lives of senior officers.[41]

The victory produced the usual spoils of war. As well as capturing all the guns on the Schellenberg the Allies captured all the regimental colours (apart from de la Colonie's Grenadiers Rouge Régiment), their ammunition, baggage and other rich booty. But the large casualty figures caused some consternation throughout the Grand Alliance.[42] Although the Dutch cast a victory medal showing Baden on the obverse and a Latin inscription on the other side, there was no mention of the Duke of Marlborough.[43] The Emperor, though, wrote personally to the Duke: "Nothing can be more glorious than the celerity and vigour with which ... you forced the camp of the enemy at Donauwörth".[44] With the town abandoned that night by Colonel DuBordet, the Elector, who had arrived within sight of the battle with reinforcements only to see the flight and massacre of his best troops, drew his garrisons out of Neuburg and Ratisbon, and fell back behind the river Lech near Augsburg.

Devastation of Bavaria

.png)

Marlborough had won his bridgehead over the Danube, and had put himself between the French and Vienna; yet the battle was followed by a curious, dragging anti-climax.[45] The Duke was determined to lure the Elector into battle before Tallard arrived with reinforcements, but since the battle on the Schellenberg neither Allied commander could agree on their next move, resulting in a protracted siege of Rain. Due to the initial lack of heavy guns and ammunition (promised by the Empire but not delivered on time) the town did not fall until 16 July.[46] Nevertheless, Marlborough promptly occupied Neuburg which, together with Donauwörth and Rain, provided the Allies with enough fortified bridges across the Danube and Lech rivers to manoeuvre with ease.[47]

The Allied commanders now marched to Friedberg, watching their enemy across the river Lech in Augsburg, at the same time preventing them from entering Bavaria or drawing from it any supplies. But the transfer of Bavaria from the party of the Two Crowns to the Grand Alliance was the prime concern to the Allies. As the Elector sat behind his defences at Augsburg Marlborough sent his troops deep into Bavaria on raids of destruction, burning buildings and destroying crops, trying to lure the Bavarian commander into battle or convince him to change his allegiance back to Emperor Leopold I. The Emperor had offered a full pardon, as well as subsidies and restoration of all his territories, with additional lands of Pfalz-Neuburg and Burgau if he returned to the Imperial fold, but negotiations between the parties were making little headway.[48]

The spoliation of Bavaria led to entreaties from the Elector's wife, Theresa Kunegunda Sobieska, for him to divest himself of the French alliance. Although the Elector wavered somewhat in his allegiance to Louis XIV, his resolve to continue fighting against Leopold I and the Grand Alliance was stiffened when news arrived that Tallard's reinforcements – some 35,000 men – would soon be in Bavaria.[49] Marlborough now intensified the policy of devastating the Elector's territory. On 16 July the Duke wrote to his friend Heinsius, the Grand Pensionary of Holland, "We are advancing into the heart of Bavaria to destroy the country and oblige the Elector one way or the other to a compliance".[50] The policy compelled the Elector to send 8,000 troops from Augsburg to defend his own property, reserving only a fraction of his army to join the French under Marsin and Tallard.[51] But although Marlborough thought it a necessary strategy to secure success, it was of doubtful morality. The Duke himself confessed his reservations to his wife, Sarah, "This is so uneasy to my nature that nothing but an absolute necessity would have obliged me to consent to it. For these poor people suffer only for their master's ambition."[50] Accounts differ as to the actual amounts of damage done. De La Colonie thought that reports of the devastation were perhaps exaggerated for propaganda purposes; yet Christian Davies serving with Hay's Dragoons wrote, "The allies sent parties on every hand to ravage the country ... We spared nothing, killing, burning or otherwise destroying whatever we could not carry off."[52] To Historian David Chandler, Marlborough must bear the full responsibility for the destruction, for although he undoubtedly found it hard to stomach it was taken under Baden's, and the Emperor's protests.[53]

There are accounts of the 1704 plundering which have been recorded in various churches of Upper Bavaria, such as in Erdweg, Petershausen, Markt Indersdorf and Dachau. The villages of Viehbach and Bachenhausen (near Fahrenzhausen, ca. 30 km north of Munich) also recorded the plundering and fires. When their homes were spared destruction, they swore a vow to forever hold a Mass every year on St. Florian's Day (May 4) to remember their deliverance. The proclamation can still be seen in the old village church in Viehbach.[54]

The failure of the Empire to provide an effective siege train had, up to this point, robbed the Allies of victory – neither Munich nor Ulm could be taken, and the Elector had neither been defeated nor compelled to change allegiance.[55] Prince Eugene had become increasingly worried that no decisive action had followed the victory on the Schellenberg, writing to the Duke of Savoy, "... I cannot admire their performances. They have been counting on the Elector coming to terms ... they have amused themselves with ... burning a few villages instead of ... marching straight upon the enemy."[56] Tallard arrived in Augsburg with French reinforcements on 5 August.[57] Eugene, shadowing Tallard, was also heading south with 18,000 men, but he had been forced to leave behind 12,000 troops guarding the Lines of Stollhofen[lower-alpha 4] with which to prevent Villeroi bringing further French reinforcements to the Danube.[58] Moreover, the Elector had at last sent orders to the large Bavarian contingents on the Tyrolese border to rejoin the main army. For the Allies, therefore, time was short: they must defeat the French and their allies at once, or all south Germany would be lost.[59]

On 7 August the three Allied commanders – Marlborough, Baden and Eugene – met to decide their strategy. To give themselves another major crossing over the Danube a plan by Baden to besiege the city of Ingolstadt with a force of 15,000 men was agreed to, despite leaving the Allied army numerically inferior.[60] This army, totalling 52,000 men and now without the commander who led the Imperial troops on the Schellenberg, would meet the Franco-Bavarian forces, numbering 56,000 men, in and around the small village of Blindheim. The engagement, fought on 13 August 1704, would become known in German as the Battle of Höchstädt, and in English, as the Battle of Blenheim.

Cultural references

- Joseph Addison's poem The Campaign

Notes

Explanatory notes

- All dates in the article are in the Gregorian calendar (unless otherwise stated). The Julian calendar as used in England from 1700 to 1752 differed by eleven days. Thus, the battle of Schellenberg was fought on 2 July (Gregorian calendar) or 21 June (Julian calendar). In this article (O.S.) is used to annotate Julian dates with the year adjusted to 1 January. See the article Old Style and New Style dates for a more detailed explanation of the dating issues and conventions.

- Exact numbers are not known.

- During the assault Baden had his horse shot from underneath him, and was severely wounded in the foot.

- The Lines of Stollhofen are a military chain of posts designed for the defence of the Rhine Valley. The lines range 20 miles (32 km) between Stollhofen, a small village on the Rhine, to the Black forest. The barrier was designed to stop the French marching down the Rhine from Strasbourg.

Citations

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 31.

- Sources vary: Chandler states 10,000; Churchill 14,000; Barnett 15,000.

- Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 137.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 173.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 356. An agent of the King of Prussia was still in the Bavarian camp, negotiating with the elector for this purpose.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 355.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 357.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 787.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 29.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 176.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 359.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 793. According to Winston Churchill there was no doubt that nearly all the generals on both sides thought it inadmissible for the Allies to fight a battle before 3 July.

- La Colonie: Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 1692–1717, 179.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 795.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 177.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 33.

- Christian Davies, known also as Mother Ross or Mrs Davies, had concealed her identity and enlisted in the army as a man in 1693.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 212.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 179.

- La Colonie: The Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 182.

- La Colonie: Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 1692–1717, 183. De la Colonie.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 360.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 179. Although Mordaunt and Munden survived the day, little more than a handful of the forlorn hope were not killed. Falkner states 17 men of the 'forlorn hope' survived the day. Trevelyan states 11 men survived (including Mordaunt).

- La Colonie: The Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 184.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 34.

- La Colonie states the defenders had 'several wagon loads' of grenades.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 35.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 362.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 36. This intelligence was discovered by a soldier who had drifted off to the right of the attack. De la Colonie states a lieutenant and 20 men were sent off to reconnoitre the area.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 36.

- La Colonie: Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 1692–717, 187. De la Colonie states the commandant thought this was the best way to secure the town, however "... the result was our ruin."

- La Colonie: The Chronicles of an Old Campaigner, 190.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 182. Spencer states that d'Arco had assumed the rest of his men had preceded him into the town but in this, he was mistaken.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 37.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 805.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 39.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 363.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 183.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 364. Of the English and Scots engaged every third man had fallen.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 806.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 184.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 191.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, 807. Medal inscription reads: The enemy defeated and put to flight and their camp plundered at Schellenberg near Donauwörth, 1704.

- Spencer: Blenheim: Battle for Europe, 192.

- Barnett: Marlborough, 100.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 367. The big guns promised Marlborough arrived late, short of ammunition, and the gunners unskilful. La Colonie and the remains of his grenadiers had retired to Rain following their defence of the Schellenberg (Churchill 811). Rain's garrison marched out with full military honours and were permitted to rejoin their army in Augsburg.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 812.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 813. It was the Elector's interest to bargain with the Allies for peace, and with France for help. In the words of Churchill, no appeal to France could be so potent as the open threat to change sides.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 44.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 368.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 370.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 43.

- Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 139. The French, forgetting their destruction of the Palatinate in the Nine Years' War, proclaimed that this barbarism was worthy only of the Turks. (Churchill 823).

- Schertl, Hans. "Viehbach - St.Laurentius Kirchen und Kapellen im Dachauer Land". kirchenundkapellen.de (in German).

- Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 136. The Imperialist siege train had fallen into enemy hands the previous year. Other guns had been held up at Mainz and Nuremberg. When some guns arrived they were, in Churchill's words, 'weak and ill-equipped'.

- McKay: Prince Eugene of Savoy, 84.

- Lynn and McKay put this date at 3 August.

- Falkner: Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory, 44. Falkner states Eugene's reinforcements numbered 20,000.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 371.

- Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 279. To Mérode-Westerloo, and subsequent historians, this decision was largely a ploy to remove the cautious and obstructive Baden from the decisive battle. However, to Historian Richard Holmes there was no 'trace of subterfuge' in this decision, and to Marlborough the siege made perfect strategic sense.

References

Primary

- La Colonie, Jean Martin de (1904). The Chronicles of an Old Campaigner (trans. W. C. Horsley).

Secondary

- Barnett, Correlli (1999). Marlborough. Wordsworth Editions Limited. ISBN 978-1-84022-200-5.

- Chandler, David G (2003). Marlborough as Military Commander. Spellmount Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86227-195-1.

- Churchill, Winston (2002). Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, vol. II. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10633-5.

- Falkner, James (2004). Blenheim 1704: Marlborough's Greatest Victory. Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84415-050-2.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-722571-2.

- Lynn, John A (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-05629-9.

- McKay, Derek (1997). Prince Eugene of Savoy. Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-87007-1.

- Spencer, Charles (2005). Blenheim: Battle for Europe. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36704-7.

- Trevelyan, G. M. (1948). England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim. Longmans, Green and co.