Canton Bulldogs–Massillon Tigers betting scandal

The Canton Bulldogs–Massillon Tigers betting scandal was the first major scandal in professional football in the United States. It refers to a series of allegations made by a Massillon, Ohio newspaper charging the Canton Bulldogs coach, Blondy Wallace, and Massillon Tigers end, Walter East, of conspiring to fix a two-game series between the two clubs. One account of the scandal called for Canton to win the first game and Massillon was to win the second, forcing a third game—with the biggest gate—to be played legitimately, with the 1906 Ohio League championship at stake. Another account accused Wallace and East of bribing Massillon players to throw a game in the series. Canton denied the charges, maintaining that Massillon only wanted to damage the club's reputation. Although Massillon could not prove that Canton had indeed thrown the second game and it remains unknown if there was ever a match-fixing agreement, the scandal tarnished the Bulldogs name and reportedly helped ruin professional football in Ohio until the mid-1910s.

Rivalry

From 1905 until 1906, the Bulldogs and Tigers were arguably the best two teams in the country. Located just 15 miles apart in Stark County, both teams were constantly fighting to recruit the best players in football. In fact the Bulldogs, or Canton Athletic Club as they were called at the time, formed their football team in 1905 with the sole objective of beating the Tigers, who had won every Ohio League championship since 1903.[1]

Both teams spent lavish amounts of money to bring in ringers from out-of-town. The very first Canton-Massillon game was played on November 30, 1905. The game was the season finale for both clubs. Up until that finale game, Massillon had posted an 8–0 record, while Canton posted an 8–1 record, with only a 6–0 loss against the Latrobe Athletic Association from Pennsylvania. Massillon went on to win the game 14–4. The victory brought the Tigers the Ohio League championship for the third consecutive season.[1]

1905–06 off-season

Financial charges

In the off-season prior to the 1906 season, a news story in The Plain Dealer alleged that the Canton Athletic Club was financially broke and could not pay its players for the final game of 1905. The club denied the allegation and insisted that every dollar promised had indeed been delivered. Many Canton followers believed the story had originated in Massillon as a trick to discredit their team and make it tougher for Canton to recruit players for 1906. Massillon coach, Ed Stewart, who had newspaper connections, was believed by Canton to have planted the story. However, while Canton was in fact losing money in 1905, a group of area businessmen shouldered the losses. [2]

In a counter-charge, Canton insisted that the Tigers were also deeply in debt. However, a statement by the Tigers showed $16,037.90 in receipts and only $16,015.65 in expenditures. The only problem with Massillon's figures was that they only listed salaries, including railroad fare, at $6,740.95, which means the players were getting only about $50 per game. However, it is believed, like with Canton, that Massillon's area boosters picked up whatever losses the Tigers incurred during 1905.[3][2]

Recruitment

For the 1906 season, Canton's coach Blondy Wallace signed the entire 1905 Massillon Tigers' backfield to play for Canton.[4] While in Massillion, Ed Stewart was promoted from head coach to manager, replacing J.J. Wise. Meanwhile, Sherburn Wightman, who played under Amos Alonzo Stagg, while attending the University of Chicago, was named the team's new coach.[2]

The series

Scheduling

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Date | November 16, 1906 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadium | Mahaffey Park, Canton, Ohio | ||||||||||||||||||

| Referee | Big Bill Edwards | ||||||||||||||||||

| Attendance | 8,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

An earlier agreement between the two clubs called for each home team to receive 60 percent of the gate admission and reserved seating rights. However, Massillon disliked the deal because Canton would receive more money for the games, since their stadium was larger, and the game at Canton would be played in October, instead of the November weather to be seen in Massillon. This led the Tigers to ask that the game, to be held in Massillon, be played on Thanksgiving Day, when every football fan would attend regardless of the weather. However that October, Wallace traveled to Pennsylvania to recruit players for the upcoming game against Massillon. There he scheduled a Thanksgiving Day game against the Latrobe Athletic Association, who was the top team in Pennsylvania, and one of the toughest squads in the country. The Latrobe squad featured star quarterback John Brallier, and dealt Canton a defeat in 1905.[2]

Finally, the teams agreed to play two games of football against other in November and share equally the gate receipts. The Canton home game was slated for Friday, November 16; while the Massillon home game come on Saturday, November 24, the weekend before Thanksgiving. However, many Tigers followers felt that the scheduling of the Canton-Latrobe game was only a ploy to get Massillon to agree to lesser terms. Therefore, language was added to the agreement that if Massillon did anything to disrupt the Canton-Latrobe game, they would lose all of their gate money from their first game at Canton to the Bulldogs. The money from the November 16 was held in escrow in a Canton bank. To ensure that the Thanksgiving Day game between Latrobe and Canton was legitimate, the gate money from the second Bulldogs-Tigers was also kept on hold, this time at Merchants' National Bank in Massillon. If the Canton-Latrobe game never occurred, then Massillon would be entitled to all of Canton's gate money from the second Canton-Massillon game. Each team was also required to put up a $3,000 bond, as insurance that each team would show on the game days.[2]

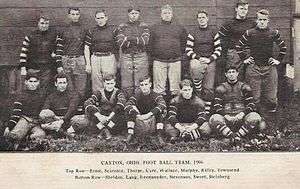

Game 1

To prepare for their series against Massillon, Blondy Wallace took his team on the campus of Penn State University to conduct drills and practices. There Nittany Lions coach, Tom Fennell, gave Canton, now officially called the "Bulldogs", special instructions in the use of the forward pass. The much anticipated first Canton-Massillon game was finally held at Canton's Mahaffey Park. It was the biggest football game yet in Ohio, even bigger than the clubs' 1905 game. The Bell Telephone Company even had men stationed in the grounds observing. As fast as a play was made, it was telegraphed to every major city in the United States.[5] The first game went to Canton by a score of 10–5.[2]

Game 2

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Date | November 24, 1906 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadium | Hospital Grounds Stadium, Massillon, Ohio | ||||||||||||||||||

| Attendance | 8,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

Big games, like these, always brought out theories of a fix. However, Massillon's Ed Stewart stated that it would be impossible to fix the coming game, stating that an entire team, not just certain players would have to be involved. "Big Bill" Edwards, a former player from Princeton officiated the game, and kept both teams in check.

However things became more heated for second game. The Tigers vowed to defeat Canton with their same roster from November 16, while Bell Telephone again announced it would telegraph a play-by-play account of the second game. The only roster change occurred when the Bulldogs signed Eddie Wood, a regular end from the Latrobe Athletic Association, to play in the rematch for an injured player named Gilchrist. Meanwhile, Stewart announced that "Big Bill" Edwards would be unavailable to referee because he'd be officiating that year's Yale-Harvard game. Edward Whiting of Cornell University, who'd umpired the first game at Canton, agreed to bring a replacement referee with him.[2][5]

Prior to the start of the game, a disagreement over which ball to use occurred. Massillon showed up with a ball, several ounces lighter than the Spalding brand ball Canton was used to. Blondy Wallace protested that ball made by Spalding was the norm, however, Massillon was adamant about keeping the lighter ball, which was provided to the Tigers by Ed Stewart. Wallace's protest fell on deaf ears, and was told by game's officials that he could either accept the lighter ball or forfeit both the game and the $3,000 guarantee. Historians believe that reason for Massillon's insistence for lighter ball was to help their kicking game. The Bulldogs, coming off of their 10–5 win a week ago, was favored to win the game. However, Massillon outplayed Canton and won the rematch 13–6 and was named the Ohio League's 1906 champions for the fourth straight year.[2][4][5]

Scandal

Once the game was over, Canton's coach, Blondy Wallace, in a show of sportsmanship, joined the Massillon celebration and congratulated the Tigers on their championship. However, the evening after the second game at the Courtland Hotel Bar, a brawl erupted among several of the Canton players and fans over allegations that the game had been fixed.[5] Jack Cusack, who would become the owner and manager of the Canton Bulldogs from 1912 until 1915, wrote in his book Pioneer in Pro Football that the fight was started by Cusack's neighbor, Victor Kaufmann, a physician who suffered heavy betting losses on the disputed contest. Cusack stated that he went with Kaufmann to the Courtland Hotel Bar, where Kaufman loudly made allegations of a fix. A large bar fight started in the hotel's bar area and quickly spread onto the street. Police were then called to break-up the disturbance, but Cusack and Kaufmann reportedly avoided arrest.[6]

Meanwhile, Massillon's Ed Stewart, through his newspaper Massillon Independent, charged that an actual attempt was made to bribe some of the Tiger players into throwing the game and that Blondy Wallace had been involved.[5] One story suggested that Canton players had bet large amounts of money on themselves to win, while approaching the Massillon players and asking them to throw the game in exchange for a share of Canton's winnings.

Some Canton followers then wondered if Wallace threw the game to Massillon in order to collect on some of the game's wagers. At first the play-calling strategy of Wallace was the focus of suspicion, but as the scandal grew, a number of contradictory allegations came out.[2] Canton denied the charges, maintaining that Massillon only wanted to ruin the club's reputation before their final game against the Latrobe Athletic Association on Thanksgiving Day. Canton's counter-charge was that the scandal was designed by the Tigers to cripple the Bulldogs financially by destroying the gate revenue for the Latrobe game. Massillon could not prove the charge, however, the stands were almost empty for the Thanksgiving Day Latrobe-Canton game, leaving Canton unable to pay their players.[4]

Inaccuracies and outcomes

Harry March

In 1934 Pro Football: Its Ups and Downs, a historically inaccurate book documenting early professional football, was published. The book documented the scandal and was used by sports historians for the next 70 years.[7] The author of this book was Dr. Harry A. March was a former player at Mount Union College, an executive for the New York Giants from 1925 to 1936 and later an organizer of the second American Football League. However, March also practiced medicine in Canton in 1906 and was named one of the Bulldogs team doctors.[2][8]

Of the incident, March stated that Wallace persuaded an unnamed Canton player to deliberately throw the game. When accused by his teammates, this player said he had simply obeyed orders. The player then quickly left town, on the first available train, while still in his uniform. The Professional Football Researchers Association has identified this player, as Eddie Wood of Latrobe. March gave the impression that he was running for his life from angry fans and teammates. However, even before the second Canton-Massillon game began, it was announced that Wood would be on the first train back to Latrobe, once the game ended. Not to mention that when Wood returned on the following Thursday with the Latrobe team, he was not attacked by the fans or his ex-Canton teammates. Also Wood scored the Bulldogs only score of the game. As for following Wallace's orders, Wood often crashed the middle of the field on defense, allowing the Tigers to escape outside. However, Massillon was historically known for running up the middle of field.[2]

Ed Stewart

Massillon manager Ed Stewart never stated that which Canton-Massillon game was fixed. Instead his accusation was that an attempt had been made to bribe some Massillion players before the first game. According to Stewart, Massillon players, Tiny Maxwell and Bob Shiring had been solicited to throw the first game by Walter East, a baseball player-turned end, who claimed to be backed by $50,000. Maxwell and Shiring then reported the offer to Tigers' coach Sherburn Wightman and the scandal ended before it began. East was then released by the Tigers. Only then was Wallace named by Stewart of being East's accomplice.[2]

Walter East and Sherburn Wightman

When East returned to Akron, he accused the Tiger's coach Sherburn Wightman of masterminding the scandal. According to East, Wightman had first asked him to solicit Maxwell and Shiring and have them throw the game, he then had East find a backer who would pay Wightman $4,000. However Wightman backed out of the deal at the last minute. He later went on to add that no member of the Bulldogs or their backers, as far as he knew, were connected with the deal. He finally stated that the only reason that Stewart went public on scandal was to ruin the attendance for the Canton-Latrobe game. East then gave the Akron Beacon-Journal a copy of a contract in which Wightman agreed to have the first Canton-Massillon game thrown for $4,000. The contract was signed by East, Wightman and John T. Windsor, one of the owners of East's Akron baseball team.[2] It should also be noted that East, boasted of fixing a college football game, as well as a baseball game in 1905. Meanwhile, Windsor admitted to his part in the scheme, backing up East's story. He said that he never even met Wallace.[2]

In an interview to The Plain Dealer, Wightman stated that the contract signed by himself, East and Windsor was done in accordance with instruction from Ed Stewart and the backers of the Massillon team. He stated that he reported East's scheme to Stewart, and was told to go along with deal to see which Massillon players would agree to throwing the game and then remove them from the team. He then stated that he kept up the act until he had the signatures of East and Windsor down on paper. Only then was East released from the team. Stewart defended the coach, agreeing that Wightman had entered into the contract with East and Windsor at the behest of the Tiger backers in order to get the goods on the fixers.[2]

Back in Akron, Walter East was seen as being the hapless victim of a crooked team. He was retained as manager of the Akron baseball team for the 1907 season. However, he was later fired after the team began losing.

Blondy Wallace

The scandal caused Wallace to file a libel lawsuit against Stewart and the Massillon Independent for $25,000, with Wallace claiming that his good name and professional credit have been ruined due to the paper's story. However, his libel suit never came to trial, and it is believed that he may have settled the case out of court. By this time, Wallace was too deep in debt to turn down any reasonable cash offer. He later became a bootlegger in Atlantic City and was, for a time, under federal indictment. As for the scandal, the lack of a trial left the details of the events still disputed by historians and football fans alike. Because Wallace possibly settled out of court, there was no real conclusion to the fix scandal—just charges and countercharges.[2] Due to Harry March's book, Wallace was seen as being responsible for the scandal for the next 70 years.

The Bulldogs

The Bulldogs defeated Latrobe 16–0 in front of their smallest crowd in years, 1,200 fans. Canton blamed the scandal for the small crowd, however, some believe that once the Bulldogs lost to Massillon, many fans lost interest in football. Therefore, regardless of a scandal, the game's attendance still would have fallen well below expectations. Canton players were not paid as a result, in addition. To help pay for the Latrobe team's expenses an effort was established in Latrobe, which raised part of the team's $300 expense debt, and the balance of the money was borrowed by the YMCA so that it could be paid.[9]

Meanwhile, the Tigers traveled to Chicago to beat the "All-Western" team. The attendance for that game was a mere 2,000 spectators.[2]

The timing of the betting scandal being made public damaged Canton far more than Massillon. Many allegations stated that Canton threw the second game of series, however, if the story had broken after Massillon's earlier loss to Canton, the Tigers would have been more damaged. However, the scandal engulfed both teams and forced them to fold. Although Massillon could not prove that Canton had indeed thrown the game, it so tarnished Canton's name that virtually no one attended the Latrobe game. The Bulldogs, including Wallace, were now broke. A story by the Pittsburgh Post estimated that team still owed its players $6,000 for the 1906 season. A benefit game between Massillon and Canton to help pay the Bulldog players only drew 500 fans and resulted in a 5–5 tie.[2] The proceeds from the game was only enough to get the remaining Canton players a train ticket home.

The Tigers

The Tigers were also financially broke. However, the team still had enough money to pay its players. The Massillon-area fielded a team of locals in 1907. The "All-Massillons" under Sherburn Wightman went on to win the 1907 Ohio league championship. Wightman and Stewart were still held in high regard in Massillon.[10]

Impact on Ohio pro-football

The scandal was thought to have ruined professional football in Ohio until the mid 1910s. However, the argument can be made that the expense of placing all-star teams on the field each week, also put a hamper on the sport. The Canton Morning News put a $20,000 price tag on the Massillon Tigers 1906 team, while many speculate that the cost of the Bulldogs probably even higher. Still others contend that the games involving top teams like Canton and Massilon were too one-sided and lacked excitement. Many towns in Ohio still fielded clubs over the next several years, and these new pros were consisted more of hometown talent, with only the occasional ringer.[2] Peggy Parratt, Massillon's quarterback, stayed in Massillon for the 1907 season, but he then began moving from team to team in the region, racking up Ohio League titles on a nearly annual basis. A second incarnation of the Bulldogs would be established in 1911 and would later go to win two championships in the National Football League. The diminished stature of Ohio pro football led to other areas of the country building top professional teams, including the Washington Vigilants.[10]

References

- PFRA Research. "Challenge From Canton" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2012.

- "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2010.

- Peterson, Robert W. (1997). Pigskin: The Early Years of Pro Football. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511913-4.

- Ross, Charles K. (2001). Outside the Lines. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-7496-2.

- Lahmen, Sean. "Canton vs. Massillon, 1906". In Lahmen's Terms. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- Cusack, Jack (1987). "Pioneer in Pro Football" (PDF). Professional Football Researchers Association (8). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2012. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- "Sport: Football, Oct. 12, 1936". Time. October 12, 1936. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- "Pro Football, Its Ups and Downs" Harry March, J. B. Lyon Company, Albany, NY 1934

- Van Atta, Robert (1980). "Latrobe, PA: Cradle of Pro Football" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association. 2 (Annual): 1–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- PFRA Research. "Glamourless Gridirons: 1907–09" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2012.