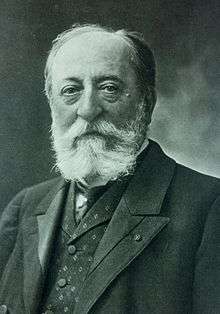

Symphony No. 3 (Saint-Saëns)

The Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78, was completed by Camille Saint-Saëns in 1886 at what was probably the artistic peak of his career. It is also popularly known as the Organ Symphony, even though it is not a true symphony for organ, but simply an orchestral symphony where two sections out of four use the pipe organ. The composer inscribed it as: Symphonie No. 3 "avec orgue" (with organ).

Of composing the work Saint-Saëns said "I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again."[1] The composer seemed to know it would be his last attempt at the symphonic form, and he wrote the work almost as a type of "history" of his own career: virtuoso piano passages, brilliant orchestral writing characteristic of the Romantic period, and the sound of a cathedral-sized pipe organ.

The symphony was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society in England, and the first performance was given in London on 19 May 1886, at St James's Hall, conducted by the composer. After the death of his friend Franz Liszt on 31 July 1886, Saint-Saëns dedicated the work to Liszt's memory. The composer also conducted the symphony's French premiere in January 1887.[2]

Structure

Although the symphony seems to follow the normal four-movement structure, and many recordings divide it in this manner, it was actually written in two movements: Saint-Saëns intended to create a novel two-movement symphony. The composer did note in his own analysis of the symphony, however, that while it was cast in two movements, "the traditional four movement structure is maintained."

A typical performance of the symphony lasts about 35 minutes. One of its most outstanding and original features is Saint-Saëns' ingenious use of keyboard instruments—piano, scored for both two and four hands at various places, and the pipe organ (Saint-Saëns was famous as an organist in 19th-century Paris). The symphony makes cyclic use of its thematic material, derived from fragments of plainsong, as a unifying device; each melody appears in more than one movement. Saint-Saëns also employs Liszt's method of thematic transformation, so that these subjects evolve into different guises throughout the duration of the symphony.[3][4]

Instrumentation and score

The symphony is scored for an orchestra comprising 3 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, piano (two and four hands), organ, and strings.

- Adagio – Allegro moderato – Poco adagio

- Allegro moderato – Presto – Maestoso – Allegro

After its slow introduction, the first movement leads to a theme of Mendelssohnian (or Schubertian) character, followed by a second subject of a gentler cast, with various secondary themes played in major, and soon after repeated in minor forms; chromatic patterns play an important role in both movements. This material is worked out in fairly classical sonata-allegro form, and gradually fades to a quieter mood, which becomes a slightly ominous series of plucked notes in cello and bass, ending on a G pitch, followed by a slow and soft sustained A♭ note in the organ, resolving into the new key of D♭ major for the Poco adagio section of the movement. This evolves as a beautiful dialogue between organ and strings, recalling the earlier main theme of the movement before the recapitulation. The movement ends in a quiet morendo.

The second movement opens with an energetic string melody, which gives way to a Presto version of the main theme, complete with extremely rapid scale passages in the piano. The Maestoso is introduced by a full C major chord in the organ. Piano four-hands is heard at the beginning with the strings, now playing the C major evolution of the original theme. The theme is then repeated in powerful organ chords, interspersed with brass fanfares. This well-known movement is considerably varied, including as it does polyphonic fugal writing and a brief pastoral interlude, replaced by a massive climax of the whole symphony characterised by a return to the introductory theme in the form of major scale variations.

Performances

The first performance was given in London on 19 May 1886, at St James's Hall, conducted by the composer. The French premiere was on 9 January 1887, conducted by the composer, at a concert of the Société des Concerts.[2] The United States premiere was given on 19 February 1887, conducted by Theodore Thomas, at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York City.[2] In May, 1915, Saint-Saëns traveled to San Francisco as France's Official Representative to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. He attended a performance of the Symphony No. 3 at the 3,782 seat Festival Hall. Karl Muck conducted the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. The composer was given a standing ovation at the performance, which was also attended by composer John Philip Sousa. Saint-Saëns composed another piece especially for the occasion called "Hail California," which included Sousa's famous band.[5]

The symphony was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the 2009 BBC Proms season as the finale to a concert celebrating the 800th anniversary of the University of Cambridge, as the composer was awarded an honorary doctorate by the university in 1893.[6] In the 2011 season, it was performed again by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and in 2013, it returned to the BBC Proms, this time with Paavo Järvi conducting the Orchestre de Paris.[7]

Recordings

The symphony continues to be a frequently performed and recorded part of the standard repertoire. One of the most renowned recordings is by Charles Munch leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Berj Zamkochian at the organ. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra recorded the Symphony No. 3 several times, with Virgil Fox, E. Power Biggs, and Michael Murray as the organists.

In 2006, the Ondine label recorded Olivier Latry performing the symphony at the inaugural concert of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ in Verizon Hall, with Christoph Eschenbach conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. Ondine released the recording in 2007 on SACD in 5.0 surround sound.[8] Another well-regarded recording of the work is the Mercury Records "Living Presence" recording made in 1957 with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under Paul Paray with Marcel Dupré on organ. It has been reissued on CD as Mercury #432719-2. Simon Preston made a recording in 1986 with James Levine conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for Deutsche Grammophon.[9]

Source of the themes

Influences

The Dutch conductor Daan Admiraal has noticed a strong relationship to various Gregorian Alleluia chant-formulas, especially for the major form of the principal theme of the Maestoso to Sacratum hoc templum Dei.[4]

It has also been suggested that themes within the symphony could be derived from the Gregorian plainsong melody Dies Irae, the Sequence for the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass.[10][11] While this may not constitute as straightforward a use of the Dies Irae theme as can be found in such works as the Totentanz of Franz Liszt, the Maestoso melody and chord progression might also be seen as a direct quote of the Ave Maria attributed to Franco-Flemish Renaissance composer Jacques Arcadelt from an 1842 arrangement by French composer Pierre-Louis Dietsch (1808-1865), which Liszt also arranged for solo piano and published in 1865 as Chanson D'Arcadelt "Ave Maria" (S.183).

Modern interpretations

The entire main theme of the Maestoso was later adapted and used in the 1977 pop-song "If I Had Words" by Scott Fitzgerald and Yvonne Keeley. The Maestoso movement is also included as the final piece of music in the soundtrack for the film Impressions de France, which plays in the France pavilion at Epcot at the Walt Disney World Resort. The song and the symphony were used as the main theme in the 1995 family film Babe and its 1998 sequel Babe: Pig in the City and can be heard in the 1989 comedy How to Get Ahead in Advertising.

The piece is also featured in the Blue Stars Drum and Bugle Corps 2008 show "Le Tour: Every Second Counts" in the finale. The tune of the symphony also serves as the national anthem of the micronation of the Empire of Atlantium under the name "Auroran Hymn". Although not included in the soundtrack, the Maestoso movement can be heard along with Dvořák's 9th Symphony in Emir Kusturica's film Underground. The Maestoso also served as the opening work on Laserium's first all-classical show (and the first to have an actual plot), Crystal Odyssey. The composer Philip Sparke created a brass band test piece based on the symphony which was then assigned to Fourth Section bands for the National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain in 2010.

References

- Camille Saint-Saëns quoted in David Dubal, The Essential Canon of Classical Music, New York, 2003, p. 337.

- BSO Program Notes Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Service, Tom (25 February 2014). "Symphony guide: Saint-Saëns's Third (the Organ symphony)". the Guardian.

- "Saint-Saëns, Symphony 3 'Organ'. A short introduction with 15 musical examples". Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- "Saint-Saëns: "Finale" to HAIL! CALIFORNIA". Mad Monk Music Press. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- "Proms 27 July 2009". BBC Proms.

- "Proms 67 Sep 2013". BBC Proms.

- "Ondine Release". www.ondine.net.

- "SAINT-SAËNS / DUKAS / BERLIOZ Levine - Download - Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft". www.deutschegrammophon.com.

- "Houston Symphony Blog". Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- "Saint-Saens' Organ Symphony: the work that could not be surpassed". Retrieved 2017-05-03.

Further reading

- Deruchie, Andrew. 2013. The French Symphony at the Fin de Siècle. New York: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-382-9. Chapter 1.

External links

- Symphony No. 3: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Full score of this piece

- West Point Military Band; Diane Bish (organ). Saint Saëns, Finale From Symphony No. 3. YouTube.

- Camille Saint-Saëns' "Organ-Symphony". Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra (together with works of Debussy and Fauré).