Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge

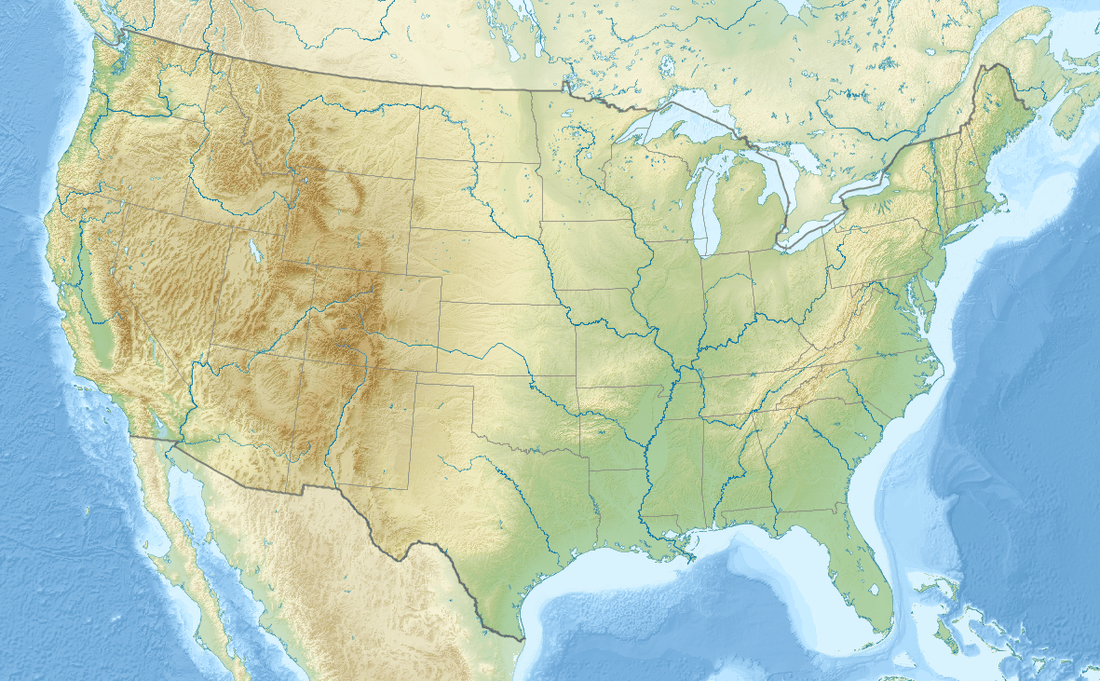

Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (CPNWR) is located in southwestern Arizona in the United States, along 56 miles (90 km) of the Mexico–United States border. It is bordered to the north and to the west by the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, to the south by Mexico's El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, to the northeast by the town of Ajo, and to the southeast by Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

| Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge | |

|---|---|

IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) | |

El Camino Del Diablo at the eastern entrance to CPNWR, 2014 | |

Map of the United States  Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (Arizona) | |

| Location | Yuma County / Pima County, Arizona, United States |

| Nearest city | Yuma, Arizona |

| Coordinates | 32°19′N 113°26′W |

| Area | 860,010 acres (3,480.3 km2)[1] |

| Established | 1939 |

| Governing body | United States Fish and Wildlife Service |

| Website | Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge |

Located within the Yuma Desert, a lower-elevation section of the Sonoran Desert, the refuge was originally established in 1939 to protect desert bighorn sheep.[2] It is home to more than 275 different species of animals and nearly 400 species of plants.[3]

CPNWR is the third largest national wildlife refuge in the lower 48 states. Its total area is 860,010 acres (3,480 km2),[1] which is greater than that of the state of Rhode Island. The refuge is administered from a small headquarters building, located in Ajo.

The area is an active corridor for illegal entry and smuggling into the U.S.[4] Since 2017 the skeletal remains of at least forty people have been found here, migrants crossing who died due to lack of water and/or from extreme temperatures. The Trump administration tightened rules against leaving food, water and clothing in such areas even if meant to save lives. Humanitarian aid volunteers were convicted of a misdemeanor in 2019 for doing so, and the incident touched off a debate about moral authority.[5][6]

Etymology

Spanish for "dark head," the refuge's name comes from the Cabeza Prieta Mountains in the refuge's northwest part.

Wilderness designation

803,418 acres (3,251 km2) — amounting to 93% of the total area of CPNWR — was preserved in 1990 as the Cabeza Prieta Wilderness.[7] Author Edward Abbey, a frequent visitor, described the refuge as "the best desert wilderness left in the United States"[8] and is reputedly buried there.

Access

There are only three public-use roads in the refuge: El Camino Del Diablo, Christmas Pass Road and Charlie Bell Road. All of these are unpaved, and they are frequently very difficult to travel because of deep mud and sand, sharp rocks, vegetation, and other obstacles. Four-wheel drive vehicles are required on El Camino Del Diablo and Christmas Pass Road. Charlie Bell Road can be traversed in a 2-wheel drive vehicle, provided the vehicle has a high clearance.[9]

There are no facilities on the refuge, including gasoline, sanitation or potable water. Visitors are advised to carry two spare tires and other spare mechanical parts in case of a breakdown.[9]

Parts of the refuge are sometimes temporarily off-limits to visitors during training exercises on the adjacent Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, or because of law enforcement concerns with respect to illegal trafficking of people and drugs from Mexico.[10][11] Additionally, parts of the refuge are temporarily off-limits to visitors between mid-March and mid-July, during the fawning season for the Sonoran pronghorn (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis), an endangered species endemic to the Sonoran Desert. The purpose of this closure is to minimize disturbance to herds containing fawns, which can result in the loss of fawns.[12]

Fauna

CPNWR is located within the Yuma Desert, a lower-elevation section of the Sonoran Desert. Despite the harshness of the desert environment, the refuge is home to more than 275 different species of animals and nearly 400 species of plants. Many species of birds are permanent residents of CPNWR, while many others migrate through during the spring and fall.[3] Most of the fauna are xerocoles, and they tend to be either nocturnal or crepuscular, most active at dawn and dusk so as to escape the heat.

These fauna include:[13]

- American badger (Taxidea taxus berlandieri)

- Arizona pocket mouse (Perognathus amplus)

- Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus pallidus)

- Big free-tailed bat (Nyctinomops macrotis)

- Black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus)

- Bobcat (Lynx rufus baileyi)

- Broad-billed hummingbird (Cynanthus latirostris)

- Collared peccary (Pecari tajacu)

- Common collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris)

- Cougar (Puma concolor)

- Coyote (Canis latrans)

- Curve-billed thrasher (Toxostoma curvirostre)

- Desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni)

- Desert kangaroo rat (Dipodomys deserti)

- Desert pocket mouse (Chaetodipus penicillatus)

- Elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi)

- Gambel's quail (Callipepla gambelii)

- Giant desert hairy scorpion (Hadrurus arizonensis)

- Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), a near-threatened species

- Gila woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis)

- Golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)

- Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

- Greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus)

- Harris's antelope squirrel (Ammospermophilus harrisii)

- Kit fox (Vulpes macrotis)

- Lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae)

- Morafka's desert tortoise (Gopherus morafkai), a vulnerable species

- Desert mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus eremicus)

- Phainopepla (Phainopepla nitens)

- Red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis)

- Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus yumanensis)

- Round-tailed ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus tereticaudus)

- Sonoran Desert centipede (Scolopendra polymorpha)

- Sonoran Desert sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes cercobombus)

- Sonoran pronghorn (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis), an endangered species

- Vermilion flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus)

- Western pipistrelle (Pipistrellus hesperus)

- Western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis leucoparia)

History

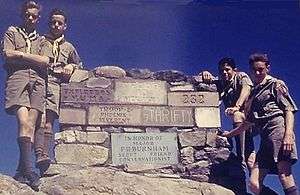

In 1936, the Arizona boy scouts mounted a statewide campaign to save the desert bighorn sheep, leading to the creation of CPNWR. The Scouts first became interested in the sheep through the efforts of Major Frederick Russell Burnham, the noted conservationist who has been called the "Father of Scouting". Burnham observed that fewer than 150 of these sheep still lived in the Arizona mountains. He called George F. Miller, then scout executive of the boy scout council headquartered in Phoenix, with a plan to conserve them.[14]

Several other prominent Arizonans joined the movement and a Save the Bighorns poster contest was started in schools throughout the state. The contest-winning bighorn emblem was made up into neckerchief slides for the 10,000 Boy Scouts, and talks and dramatizations were given at school assemblies and on radio. The National Wildlife Federation, the Izaak Walton League, and the National Audubon Society also joined the effort.[14]

On January 18, 1939, over 1,500,000 acres (6,070 km2) of Arizona were set aside at CPNWR and at Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was set up to develop high mountain waterholes for the sheep. A brick and stone monument was erected on a hill near Tule Well, and Major Burnham delivered the dedication speech opening CPNWR in 1941.

The desert bighorn sheep is now the official mascot for the Arizona Boy Scouts and the number of sheep in these parks have increased substantially.[14] In 1989, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of this refuge, the stone monument on the site was re-dedicated to the Arizona Boy Scouts and Major Burnham.[15]

Gallery

- Tule Well, located on El Camino Del Diablo in CPNWR (2014)

- El Camino Del Diablo at the eastern entrance to CPNWR, 2014

Wildflowers at CPNWR

Wildflowers at CPNWR Sunset at CPNWR

Sunset at CPNWR- Brick and stone monument at Tule Well commemorating the dedication of CPNWR, 2014

See also

- Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge

- Category: Fauna of the Sonoran Desert

- Category: Protected areas of the Sonoran Desert

- Gran Desierto de Altar

- List of flora of the Sonoran Desert Region by common name

- Sierra Pinta

- Tule Desert (Arizona)

- El Camino del Diablo

Notes

- Center for Biological Diversity (2011-05-19). "Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge Puts Fragile Pronghorn Population at Risk From Motorized Mayhem". Press releases. Tucson, Arizona: Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved 2014-04-18.

- Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (2013). "About the Refuge". Ajo, Arizona: United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (2013). "Wildlife & Habitat". Ajo, Arizona: United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Brean, Henry (August 15, 2019). "Trump administration delays border wall work in Arizona preserves". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Gershman, Jacob (Dec 6, 2018). "Aid for Immigrants on Desert Trek Stirs Religion-Freedom Fight". Retrieved May 13, 2019 – via www.wsj.com.

- "Guilty Verdict in first #Cabeza9 case". Jan 18, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Science Applications Team; United States Fish and Wildlife Service (2013). "Bringing Sonoran Pronghorn Back from the Brink" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service: Southwest Science Applications - Our Stories. Albuquerque, New Mexico: United States Department of the Interior, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region. Retrieved 2014-04-18.

- Abbey, E (2006). Postcards from Ed: dispatches and salvos from an American iconoclast. Milkweed Press. ISBN 1-57131-284-6.

- Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (2013). "Plan Ahead". Ajo, Arizona: United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Slivka, J (2003-10-30). "Border Crime Ravaging Parks In Arizona In 'Smugglers Crescent,' Public Is Losing Out As Rangers Are Forced To Act As Border Police". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, southeast of Yuma, has more crimes per visitor than any other piece of public land in the West.

- Ingley, K (2005-05-15). "Ghost highways - Arizona desert scarred by illegal immigration traffic". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, southeast of Yuma, has more crimes per visitor than any other piece of public land in the West.

- Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (2013). "Fawning Season". Ajo, Arizona: United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Powell, TR (2014). "Animals of the Sonoran Desert and Refuge". Ajo, Arizona: Cabeza Prieta Natural History Association. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Edward H. Saxton (1978). "Saving the Desert Bighorns". Desert Magazine. 41 (3). Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- Steffens, JC; Macomber, RH (1997). "CPNWR - Tule Well". Retrieved June 30, 2013.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. |

- Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, official United States Fish and Wildlife Service website

- Cabeza Prieta Natural History Association

- The short film Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge Desert Wilderness (2006) is available for free download at the Internet Archive (produced by the National Conservation Training Center of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service)