Byronosaurus

Byronosaurus is a genus of troodontid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of Mongolia.

| Byronosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram showing known remains | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

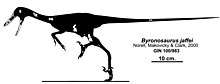

| Genus: | †Byronosaurus Norell, Makovicky & Clark, 2000 |

| Species: | †B. jaffei |

| Binomial name | |

| †Byronosaurus jaffei Norell, Makovicky & Clark, 2000 | |

Discovery and naming

In 1993, Michael Novacek, a member of an American Museum of Natural History expedition to the Gobi Desert, discovered the skeleton of a small theropod at Ukhaa Tolgod. This was further excavated in 1994 and 1995. The find was illustrated in a publication in 1994.[1] On 15 July 1996, at the Bolor's Hill site, about eight kilometers (five miles) away from the original location, a second specimen was discovered, a skull.

In 2000, Mark Norell, Peter Makovicky and James Clark named and described the type species Byronosaurus jaffei. The species name as a whole honoured Byron Jaffe, "in recognition of his family's support for the Mongolian Academy of Sciences-American Museum of Natural History Paleontological Expeditions".[2]

The holotype, IGM 100/983, was found in a layer of the Djadochta Formation dating from the late Campanian. It consists of a partial skeleton with skull. It contains a partial skull with lower jaws, three neck vertebrae, three back vertebrae, a piece of a sacral vertebra, four partial tail vertebrae, ribs, the lower end of a thighbone, the upper ends of a shinbone and calf bone, a second metatarsal and three toe phalanges. The paratype, specimen IGM 100/984, is the skull found in 1996, of which only the snout has been preserved. Both specimens are of adult individuals.[2]

In 2003, the skeleton was described in detail.[3]

In 2009, two front skulls and lower jaws of very young, perhaps newly hatched, individuals, specimens IGM 100/972 and IGM 100/974, were referred to Byronosaurus, after originally having been identified as Velociraptor exemplars.[4]

Description

Byronosaurus is a troodontid, a group of small, bird-like, gracile maniraptorans. All known troodontids share unique features of the skull, such as closely spaced teeth in the lower jaw, and large numbers of teeth. Troodontids have sickle-claws and raptorial hands, and some of the highest non-avian encephalization quotients, meaning they were behaviourally advanced and had keen senses. Byronosaurus is one of few troodontids that have no serrations on its teeth, similar to its closest relative Xixiasaurus.[5] Byronosaurus was 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long and 50 cm (20 in) tall.[6] It weighed only about 4 kilograms (9 lbs).[6] Unlike most other troodontids, its teeth seem to lack serrations. They are instead needle-like, probably best suited for catching small birds, lizards and mammals. Specifically, they resemble those of Archaeopteryx.

The holotype skull measures about twenty-three centimeters long (nine inches). The snout is pneumatised, with a sinus in each maxilla.[3]

Hatchling skulls and nests

Mark Norell and colleagues described two "perinate" (hatchlings or embryos close to hatching) specimens of Byronosaurus (specimens IGM 100/972 and IGM 100/974) in 1994. The two specimens were found in a nest of oviraptorid eggs in the Late Cretaceous "Flaming Cliffs" of the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia. The nest is quite certainly that of an oviraptorosaur, since an oviraptorid embryo is still preserved inside one of the eggs. The two partial skulls were first described by Norell et al. (1994) as dromaeosaurids, but reassigned to Byronosaurus after further study.[4][7] The juvenile skulls were either from hatchlings or embryos, and fragments of eggshell are adhered to them although it seems to be oviraptorid eggshell. The presence of tiny Byronosaurus skulls in an oviraptorid nest was considered an enigma. Hypotheses explaining how they came to be there included that they were the prey of the adult oviraptorid, that they were there to prey on oviraptorid hatchlings, or that an adult Byronosaurus may have laid eggs in a Citipati nest (see nest parasite).[8] These have all been shown to not be the case, as later a Byronosaurus nest was found two metres uphill from the oviraptorid nest, with the oviraptorid nest at the end of a drainage course from the Byronosaurus nest. The baby Byronosaurus skulls must have been washed from one nest to the other.[9] The eggs of Byronosaurus are not paired, suggesting the layer had only one egg tube, the same as in modern birds.[10] This differs from the condition in Citipati and Gigantoraptor where the eggs are laid in pairs.[11]

See also

References

- Novacek, M.J., Norell, M.A, McKenna, M.C. and Clark, J.M, 1994, "Fossils of the Flaming Cliffs", Scientific American 271(6), 60-69

- Norell, M.A., Makovicky, P.J. & Clark, J.M., 2000, "A new troodontid theropod from Ukhaa Tolgod, Mongolia", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(1): 7-11

- Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A.; Clark, J.M.; Rowe, T.E. (2003). "Osteology and relationships of Byronosaurus jaffei (Theropoda: Troodontidae)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3402: 1–32. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)402<0001:oarobj>2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Bever, G.S. and Norell, M.A. (2009). "The perinate skull of Byronosaurus (Troodontidae) with observations on the cranial ontogeny of paravian theropods." American Museum Novitates, 3657: 51 pp.

- Junchang Lü; Li Xu; Yongqing Liu; Xingliao Zhang; Songhai Jia & Qiang Ji (2010). "A new troodontid (Theropoda: Troodontidae) from the Late Cretaceous of central China, and the radiation of Asian troodontids" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55 (3): 381–388. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0047.

- Montague, R. (2006). "Estimates of body size and geological time of origin for 612 dinosaur genera (Saurischia, Ornithischia)". Florida Scientist. 69 (4): 243–257.

- Mackovicky, Peter J.; Norell, Mark A. (2004). "Troodontidae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 184–195. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Norell, Mark A.; Clark, James M.; Dashzeveg, Demberelyin; Barsbold, Rhinchen; Chiappe, Luis M.; Davidson, Amy R.; McKenna, Malcolm C.; Perle, Altangerel; Novacek, Michael J. (November 4, 1994). "A theropod dinosaur embryo and the affinities of the Flaming Cliffs dinosaur eggs". Science. 266 (5186): 779–782. doi:10.1126/science.266.5186.779. PMID 17730398.

- http://dml.cmnh.org/2011Jul/msg00114.html

- https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/byronosaurus-nest-photo-amnh-m-ellison/cQFqet_4BBziYQ

- http://prehistoricbeastoftheweek.blogspot.com/2017/04/byronosaurus-beast-of-week.html

.png)

.png)