Burkittsville, Maryland

Burkittsville is a historic village in Frederick County, Maryland, United States. The village lies in the southern Middletown Valley along the eastern base of South Mountain.

Burkittsville, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| Town of Burkittsville | |

Main Street in Burkittsville | |

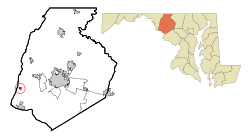

Location of Burkittsville, Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°23.5′N 77°37.6′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | 1894[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.46 sq mi (1.19 km2) |

| • Land | 0.45 sq mi (1.18 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 587 ft (179 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 151 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 165 |

| • Density | 363.44/sq mi (140.25/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 21718 |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-11400 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0589853 |

| Website | Burkittsville-MD.gov |

Burkittsville is a residential area with an economy based in agriculture and tourism. The village was the scene of the Battle of Crampton's Gap, part of the Battle of South Mountain during the Maryland Campaign of the Civil War on September 14, 1862. Burkittsville was also made a subject of national attention when it was used as the setting of the 1999 horror film The Blair Witch Project. Nearby attractions include the Gathland State Park and the Appalachian Trail.

The population was 151 as of the 2010 census.

Geography

Burkittsville is located at 39°23.5′N 77°37.6′W (39.3915, -77.6271).[5]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.45 square miles (1.17 km2), all land.[6]

_between_Main_Street_and_Lake_Side_Drive_in_Burkittsville%2C_Frederick_County%2C_Maryland.jpg)

Transportation

The main method of travel to and from Burkittsville is by road. The only significant highway serving the town is Maryland Route 17, which follows Potomac Street within the town limits. To the north, MD 17 connects to Middletown and eventually reaches Interstate 70 in Myersville. Heading south, MD 17 interchanges with U.S. Route 340 just before reaching Brunswick.

History

English settlement in this region began in the early 18th century. Land was being surveyed and patented in the south-western portion of the Middletown Valley beginning in the 1720s. The first land tract to be patented within the present boundaries of Burkittsville was "Dawson's Purchase," dated May 14, 1741.[7] The Harley/Arnold Farm, located on the western border of the village at the base of South Mountain, stands on the "Dawson's Purchase" tract.

Burkittsville was first founded by two property owners: Major Joshua Harley and Henry Burkitt. The western half was first founded as "Harley's Post Office" in 1824. After Harley's passing in 1828, Burkitt renamed it Burkittsville. Over the next thirty years it grew as a community with stores, shops, blacksmiths, a schoolhouse, and a tannery.

On September 13, 1862, Confederate cavalry under command of Colonel Thomas Munford (under General J.E.B. Stuart) occupied Burkittsville. On Sunday, September 14, the forces of the Union and Confederate armies engaged in the Battle of Crampton's Gap, a bloody prelude to the Battle of Antietam. The Reformed and Lutheran churches and adjacent schoolhouse were used as hospitals for the more than 300 wounded of both sides. These buildings still stand today.

Routinely characterized as the trigger to Antietam, victory at Crampton's Gap embodied Union Gen. George B. McClellan's strategic reaction to his acquiring the legendary “Lost Order” at Frederick which disclosed Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's campaign movements. It was McClellan's intention to “cut the enemy in two and beat him in detail”.

After seizing Crampton's Gap Gen. William B. Franklin failed to relieve the besieged Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, and more importantly to prevent Confederate generals James Longstreet and “Stonewall” Jackson from reuniting at Sharpsburg. There Lee hastily stood his ground in the mammoth battle of Antietam, the war's bloodiest day. President Abraham Lincoln then used the marginal Union victory at Antietam as a springboard to his Emancipation Proclamation which changed war aims. Without the fall of Crampton's Gap there would have been no Antietam.

Nearly all of Burkittsville is a historic district, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 20, 1975. The 300 acres (120 ha) district includes about 70 contributing structures.[8] The Burkittsville Historic District is itself part of the larger Crampton's Gap Historic District, which comprises the southern portion of the lands involved in the Battle of South Mountain, extending from the western side of Crampton's Gap, over South Mountain and about a mile to the east of Burkittsville.[9]

Blair Witch

Burkittsville gained uninvited attention with the 1999 release of the film The Blair Witch Project and the franchise it spawned. "The poor town of Burkittsville suddenly found itself overrun with Blair Witch groupies, wandering around in the woods, trying to find the 'real' places where the story had happened."[10] Contrary to popular belief, however, the majority of the film was not filmed in Burkittsville, but in Maryland's Seneca Creek State Park, about 25 miles (40 km) away,[11][12] and the events depicted in the film and the legend of the Blair Witch itself are false.[13] Furthermore, other potentially identifiable landmarks from the Blair Witch story—Coffin Rock, the Black Hills, Black Rock Road, and the local convenience store - are not located in the real Burkittsville or the immediate surrounding area, but are rather in Germantown, Maryland.

A Burkittsville town welcome sign appeared briefly in the film, which featured cursive script with black and white coloring. As thievery of the town's welcome sign became more common due to the Blair Witch's increasing notoriety, the sign was radically redesigned to feature white letters and red stars against a blue background.[14] The new sign also notes that the town has fewer than 200 people, was established in 1824, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[11] Burkittsville returned as the purported site of the film's sequel, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 in 2000. When a third film in the series was released in 2016, the town pre-emptively took down its welcome signs and blocked off alleys to deter tourists.[15]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 293 | — | |

| 1880 | 280 | −4.4% | |

| 1890 | 273 | −2.5% | |

| 1900 | 229 | −16.1% | |

| 1910 | 228 | −0.4% | |

| 1920 | 200 | −12.3% | |

| 1930 | 173 | −13.5% | |

| 1940 | 177 | 2.3% | |

| 1950 | 190 | 7.3% | |

| 1960 | 208 | 9.5% | |

| 1970 | 221 | 6.3% | |

| 1980 | 202 | −8.6% | |

| 1990 | 194 | −4.0% | |

| 2000 | 171 | −11.9% | |

| 2010 | 151 | −11.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 165 | [4] | 9.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2010 census

As of the 2010 census[3]there were 151 people, 69 households, and 42 families residing in the town. The population density was 335.6 inhabitants per square mile (129.6/km2). There were 74 housing units at an average density of 164.4 per square mile (63.5/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 99.3% White and 0.7% Asian. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.3% of the population.

There were 69 households, of which 20.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.7% were married couples living together, 4.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.1% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.19 and the average family size was 2.79.

The median age in the town was 50.5 years. 15.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 3.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 21.9% were from 25 to 44; 43.1% were from 45 to 64; and 15.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 50.3% male and 49.7% female.

2000 census

As of the census[17] of 2000, there were 171 people, 72 households, and 49 families residing in the town. The population density was 415.8 people per square mile (161.0/km2). There were 76 housing units at an average density of 184.8 per square mile (71.6/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 94.74% White, 1.17% African American and 4.09% Asian. 1.8 percent of the population is Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 72 households out of black which 30.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.1% were married couples living together, 5.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.9% were non-families. 26.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 22.8% under the age of 18, 2.3% from 18 to 24, 38.6% from 25 to 44, 28.1% from 45 to 64, and 8.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $50,313, and the median income for a family was $53,125. Males had a median income of $45,833 versus $30,417 for females. The per capita income for the town was $24,919. About 4.1% of families and 4.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including none of those under the age of eighteen and 5.6% of those 65 or over.

Points of interest

- P.J. Gilligan Dry Goods & Mercantile Co. (1821)

- Burkittsville Union Cemetery

- South Mountain Heritage Society Museum (2002)

References

- Burkittsville, Municipalities, Frederick County, Maryland. Maryland Manual On-Line. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- Tracey, Grace; Dern, John (1987). Pioneers of Old Monocacy: The Early Settlement of Frederick County, Maryland 1721-1743. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc. p. 363. ISBN 0-8063-1183-5.

- Way, Lawrence A.; Cooper, H. Austin; Stowell, Walton D.; Winslow, Barbara; Winslow, Mary K. (May 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: Town of Burkittsville". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- Phifer, Paige; Wallace, Edie; Reed, Paula (March 14, 2008). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Crampton's Gap Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- Lyman, Rick (2000-09-10). Film: Evil Lurking; Trying to Be Brilliant, Scary and Thrifty. Twice. New York Times, 10 September 2000.

- Canadian Press (2009-11-17). Maryland town where 'Blair Witch' filmed hopes new signs will deter thieves. The Canadian Press, CBCNews, 17 November 2009. Retrieved on 2009-11-17 from cbc.ca

- Goldman, Michael (1999-08). "Digital Production News; Behind the Blair Witch Project". Millimeter, August 1999.

- "The Blair Witch Cult: Two young filmmakers have set the summer--and the box office on fire with a creepy tale audiences love or hate. The making, and marketing, of a stealth smash". (August 16, 1999). Newsweek 134.7.

- Council passes budget, decides to sell sign made famous by 'Blair Witch' movie Archived June 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Burkittsville prepares for new 'Blair Witch' film

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burkittsville, Maryland. |

- Official website

- Burkittsville Facebook Page Official town Facebook Page

- Burkittsville Historic Trust National Register of Historic Places - Burkittsville Maryland

- Burkittsville, Maryland at Curlie

- South Mountain Heritage Society

- Burkittsville Preservation Association,Inc.