Buffalo Creek flood

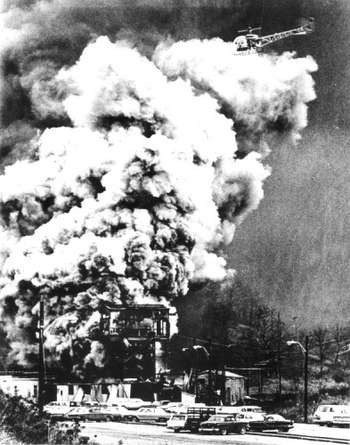

The Buffalo Creek flood was a disaster that occurred on February 26, 1972, when the Pittston Coal Company's coal slurry impoundment dam #3, located on a hillside in Logan County, West Virginia, burst, four days after having been declared "satisfactory" by a federal mine inspector.[1]

| Date | February 26, 1972 |

|---|---|

| Location | Pittston Coal Company's coal slurry impoundment dam #3, located on a hillside in Logan County, West Virginia |

| Cause | Coal Mine dam failure |

| Casualties | |

| 125 were killed, 1,121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless | |

The resulting flood unleashed approximately 132 million US gallons (500,000 cubic metres; 500 million litres) of black waste water, cresting over 30 feet (9.1 m) high, upon the residents of sixteen coal towns along Buffalo Creek Hollow. Out of a population of 5,000 people, 125 were killed, 1,121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless. 507 houses were destroyed, in addition to 44 mobile homes and 30 businesses.[1] The disaster destroyed or damaged homes in Saunders, Pardee, Lorado, Craneco, Lundale, Stowe, Crites, Latrobe, Robinette, Amherstdale, Becco, Fanco, Braeholm, Accoville, Crown and Kistler.[2] In its legal filings, Pittston Coal referred to the accident as "an Act of God."

Dam #3, constructed of coarse mining refuse dumped into the Middle Fork of Buffalo Creek starting in 1968, failed first, following heavy rains. The water from dam #3 then overwhelmed dams #2 and #1. Dam #3 had been built on top of coal slurry sediment that had collected behind dams # 1 and #2, instead of on solid bedrock. Dam #3 was approximately 260 feet (79 m) above the town of Saunders when it failed.

Investigation

Two commissions investigated the disaster. The first, the Governor's Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry, appointed by Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr., was made up entirely of either members sympathetic to the coal industry or government officials whose departments might have been complicit in the genesis of the flood. One of the investigators was Jack Spadaro, a man who devoted his time to regulating dam construction for safety. After then-president of the United Mine Workers Arnold Miller and others were rebuffed by Gov. Moore regarding their request that a coal miner be added to the governor's commission, a separate citizen's commission was assembled to provide an independent review of the disaster.

The Governor's Commission of Inquiry report[3] called for new legislation and further inquiry by the local prosecutor. The citizen's commission report,[4] concluded that the Buffalo Creek-Pittston Coal Company was guilty of murdering at least 124 men, women and children. Additionally, the chair of the citizen's commission and Deputy Director of the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources, Norman Williams, called for the legislature to outlaw coal strip mining throughout the state. Williams testified before the legislature that strip mining could not exist as a profit-making industry unless it is allowed by the state to pass on the costs of environmental damage to the private landowner or the public.[5]

The state of West Virginia also sued the Buffalo Creek-Pittston Coal Company for $100 million (equivalent to $422 million today) in disaster and relief damages, but a smaller settlement was reached for just $1 million ($4.2 million today) with Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. three days before he left office in 1977. The lawyers for the plaintiffs, Arnold & Porter of Washington, D.C., donated a portion of their legal fees for the construction of a new community center. West Virginia has yet to build the center, though the center was promised by Governor Moore in May 1972. [6]

Gerald M. Stern, an attorney with Arnold & Porter, wrote a book entitled The Buffalo Creek Disaster about representing the victims of the flood. The book includes descriptions of his experiences dealing with the political and legal environment of West Virginia, where the influence of large coal mining corporations is intensely significant to the local culture and communities. Sociologist Kai T. Erikson, son of psychologist and sociologist Erik Erikson, was called as an expert witness and published a study on the effects of the disaster entitled Everything In Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood (1978).[7] Erikson's book later won the 1977 Sorokin Award, granted by the American Sociological Association for an "outstanding contribution to the progress of sociology."[8]

Simpson-Housley and De Man (1989) found that, 17 years later, the residents of Buffalo Creek scored higher on a measure of trait anxiety in comparison to the residents of Kopperston, a nearby coal town that did not experience the flood. [9]

Results

Dennis Prince and some 625 survivors of the flood sued the Pittston Coal Company, seeking $64 million in damages (equivalent to $331.8 million today). They settled in June 1974 for $13.5 million ($70 million today), or approximately $13,000 for each individual after legal costs ($67,000 today). A second suit was filed by 348 child survivors, who sought $225 million ($1.17 billion today); they settled for $4.8 million in June 1974 ($24.9 million today). [10]

Kerry Albright became known as the "miracle baby" of the disaster. Running from the leading edge of the water, his mother threw him just above the flood level moments before she drowned. He survived with few ill effects, and was reared by his father. His survival gave hope and inspiration to other survivors.[11]

See also

- Aberfan disaster

- Coal slurry impoundment

- Martin County coal slurry spill

- Sludge

- The Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act of Man, a 1974 documentary film about the disaster

References

- Rhee, William. "Buffalo Creek Timeline | College of Law | West Virginia University". www.law.wvu.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- "Towns Along Buffalo Creek". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- "The Buffalo Creek Disaster: Official Report From The Governor's Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry" (PDF).

- "Disaster on Buffalo Creek: A Citizen's Report on Criminal Negligence in a West Virginia Mining Community" (PDF).

- Montrie, Chad (2003). To Save the Land and People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 122.

- "Rebuilding A Community: The Buffalo Creek Case". Arnold and Porter. 1996. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Kai T. Erikson (1976). Everything In Its Path. Simon and Schuster. pp. 284. ISBN 0-671-24067-6.

- Kai T. Erikson (1998), "Trauma at buffalo creek", Society, 35 (2): 153–161, doi:10.1007/BF02838138, ProQuest 206714941

- Simpson-Housley, Paul; De Man, Anton (1989). "Flood Experience and Posttraumatic Trait Anxiety in Appalachia". Psychological Reports. 64 (3): 896–898. doi:10.2466/pr0.1989.64.3.896. ISSN 0033-2941.

- "Buffalo Creek Legal Suites". www.marshall.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Buffalo Creek 'miracle baby' tells story to Reader's Digest". www.webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-29.

Bibliography

- Kai T. Erikson (1976). Everything In Its Path. Simon and Schuster. pp. 284. ISBN 0-671-24067-6.

- Gerald M. Stern, The Buffalo Creek Disaster ISBN 0-394-72343-0

External links

- "Voices of Buffalo Creek". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on April 5, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2005.

- "Buffalo Creek Flood". Marshall University Special Collections. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- "Buffalo Creek Flood". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- "Survivor recounts Buffalo Creek disaster". West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "Guide to the Council of Southern Mountains Records includes documents pertaining to Buffalo Creek interviews, articles, activism". Berea College Special Collections and Archives. Retrieved August 3, 2009.