Castle Gate Mine disaster

The Castle Gate mine disaster occurred on March 8, 1924, in a coal mine near the town of Castle Gate, Utah (now dismantled), located approximately 90 miles (140 km) southeast of Salt Lake City. All of the 171 men working in the mine were killed in the series of three violent explosions. One worker, the leader of the rescue crew, died from carbon monoxide inhalation while attempting to reach the victims shortly after the explosion.[1][2]

Explosions

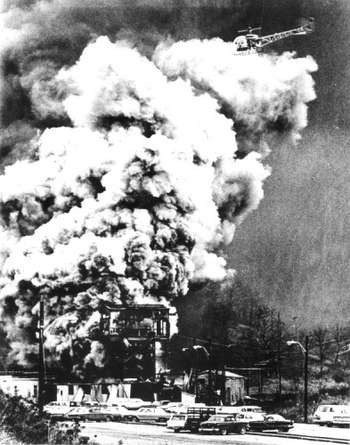

The explosions were determined to have been caused by a failure to properly dampen coal dust in the mine during the previous shift. The first blast occurred between 8:00 a.m. and 8:15 a.m. in a chamber approximately 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from the entrance to the Utah Fuel Company's Castle Gate Mine #2. A fire boss in this chamber was investigating gas near the roof of the mine when his carbide lamp went out. The miner attempted to relight his lamp with a match that ignited the gas and coal dust, setting off a gigantic explosion.[3][4]

The force of the explosion was powerful enough to launch a mining car, telephone poles, and other equipment across the canyon, a distance of nearly a mile from the entrance to the mine.[1] The steel gates of the mine were ripped from their concrete foundations. Inside the mine, rails were twisted, roof supports were destroyed, afterdamp and coal dust filled the air, and the lamps of the surviving miners were blown out. As these men attempted to relight their lamps, a second explosion was sparked, killing the remainder of the workers in the mine.[4] A third explosion occurred approximately 20 minutes later, causing a destructive cave-in.[1]

Aftermath

Recovery of the bodies took nine days. Identification of the victims was only possible, in some cases, by recognizing familiar articles of clothing. The remains of one miner were exhumed from the small cemetery near the mine entrance in order to rebury his body with his head, which was found some distance from the mine entrance subsequent to the hasty funeral service he had initially received.[5]

The nationalities of the men killed in the explosion reflect the labor force of mining industry in the United States in the early 20th century. Of the 171 fatalities, 50 were native-born Greeks, 25 were Italians, 32 English or Scots, 12 Welsh, four Japanese, and three Austrians (or South Slavs).[6] The youngest victim was 15 years old and the oldest was 73.

Two weeks prior to the explosion, the Utah Fuel Company had laid off many of the unmarried miners and miners without dependents during a period of reduced orders for coal.[1] As a result, 114 of the men who were killed in the disaster were married men, leaving behind 415 widows and fatherless children. The death benefits from the Utah State Workmen's Compensation Fund, established in 1917, provided $5,000 per dependent, paid out in $16 per week for six years. However, the Castle Gate Relief Fund, which had solicited funds from each county in Utah, continued to disburse benefits to some dependents as late as 1936.[7]

Conclusion

With this explosion, Carbon County, Utah had suffered both the worst and the third-worst mining disasters in the history of the mining industry in the United States to that point.[8] The Castle Gate mine disaster currently ranks as the 10th worst mining disaster in United States history[9] and the second worst mining disaster in the history of the state of Utah, following the Scofield Mine disaster of 1900, which killed 200 miners.

Notes

- "Hopes for Miners Fading. Head of Rescue Crew Killed by Gas in Tunnel". Ogden Standard Examiner. March 8, 1924. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Last Body Has Been Recovered from Castle Gate Disaster". Vernal Express. March 21, 1924. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Tracing Cause of Coal Mine Disaster". Salt Lake Mining Review. March 30, 1924. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- Watt 1997, p. 149.

- Watt 1997, p. 151.

- Watt 1997, p. 150.

- Watt 1997, p. 152.

- "March 8, Fourth Anniversary of Mine Disaster". News Advocate. March 8, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "The Top Ten US Mining Disasters". Epic Disasters. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

References

- Watt, Ronald G. (1997). A History of Carbon County. Utah State Historical Society. ISBN 0-913738-15-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Costa, Janeen Arnold. "Castle Gate Mine Disaster - Utah History Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2014-10-09. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

External links

- Castle Gate Relief Fund Committee Exhibit Prepared by the Utah History Research Center

- Hopes for Miners Fading. Head of Rescue Crew Killed by Gas in Tunnel Report of disaster in Ogden Standard Examiner published on day of disaster.

- Dead Brought from Mine. Rescue Workers Give up All Hope of Finding Any Survivors at Castle Gate Published in Ogden Standard Examiner March 10, 1924

- Death Claims the Castle Gate Miners Commentary published in Ogden Standard Examiner March 10, 1924

- One Family is Wiped Out Brief account, published in Ogden Standard Examiner March 10, 1924, of one miner who was killed in the Castle Gate explosion whose two older brothers were killed in the Winter Quarters explosion of 1900.

- Dead Are Being Given up at Castlegate as Rescuers Work Report of recovery efforts published in the Southern Utonian March 20, 1924

- Last Body Has Been Recovered from Castle Gate Disaster Article in Vernal Express describes the recovery of the last two bodies and how the town is adapting 10 days after the disaster.

- "Will You Help These Fatherless Children?" Published plea in the Box Elder April 15, 1924, asking readers for financial assistance for the Castle Gate mine dependents.

- "Lest We Forget" Published in the News Advocate (Price, Utah) on the one-year anniversary of the Castle Gate mine disaster

- "Fourth Anniversary of Mine Disaster" Published in the News Advocate March 8, 1928