Beorhtwulf of Mercia

Beorhtwulf (Old English: [beorxtwulf], meaning "bright wolf"; also spelled Berhtwulf; died 852) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 839 or 840 to 852. His ancestry is unknown, though he may have been connected to Beornwulf, who ruled Mercia in the 820s. Almost no coins were issued by Beorhtwulf's predecessor, Wiglaf, but a Mercian coinage was restarted by Beorhtwulf early in his reign, initially with strong similarities to the coins of Æthelwulf of Wessex, and later with independent designs. The Vikings attacked within a year or two of Beorhtwulf's accession: the province of Lindsey was raided in 841, and London, a key centre of Mercian commerce, was attacked the following year. Another Viking assault on London in 851 "put Beorhtwulf to flight", according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; the Vikings were subsequently defeated by Æthelwulf. This raid may have had a significant economic impact on Mercia, as London coinage is much reduced after 851.

| Beorhtwulf | |

|---|---|

| King of Mercia | |

| Reign | 840 – 852 AD |

| Predecessor | Wiglaf |

| Successor | Burgred |

| Died | 852 AD |

| Consort | Sæthryth |

| Issue | Beorhtric Beorhtfrith |

| House | Mercia |

Berkshire appears to have passed from Mercian to West Saxon control during Beorhtwulf's reign. The Welsh are recorded to have rebelled against Beorhtwulf's successor, Burgred, shortly after Beorhtwulf's death, suggesting that Beorhtwulf had been their overlord. Charters from Beorthwulf's reign show a strained relationship with the church, as Beorhtwulf seized land and subsequently returned it.

Beorhtwulf and his wife, Sæthryth, may have had two sons, Beorhtfrith and Beorhtric. Beorhtric is known from witnessing his father's charters, but he ceased to do so before the end of Beorhtwulf's reign. Beorhtfrith appears in later sources which describe his murder of Wigstan, the grandson of Wiglaf, in a dispute over Beorhtfrith's plan to marry Wigstan's widowed mother Ælfflæd. Beorhtwulf's death is not recorded in any surviving sources, but it is thought that he died in 852.

Background and sources

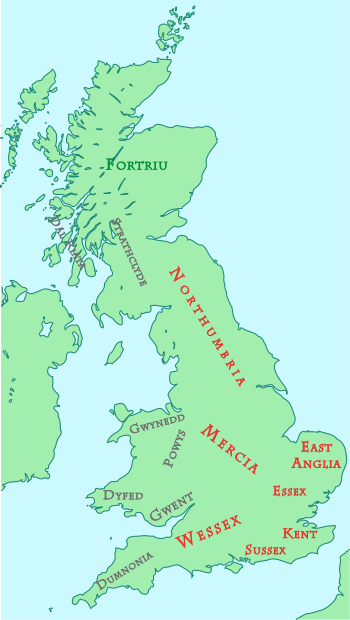

For most of the 8th century, Mercia was the dominant Anglo-Saxon kingdom.[1] Mercian influence in the south-eastern kingdoms of Kent, East Anglia, and Essex continued into the early 820s under Coenwulf of Mercia.[2] However, Coenwulf's death in 821 marked the beginning of a period in which Mercia suffered from dynastic conflicts and military defeats that redrew the political map of England.[3] Four (possibly five) kings, from what appear to be four different kin-groups, ruled Mercia throughout the next six years. Little genealogical information about these kings has survived, but since Anglo-Saxon names often included initial elements common to most or all members of a family, historians have suggested that kin-groups in this period can be reconstructed on the basis of the similarity of their names. Three competing kin-groups are recognizable in the charters and regnal lists of the time: the C, Wig and B groups. The C group, which included the brothers Coenwulf, Cuthred of Kent, and Ceolwulf I, was dominant in the period following the deaths of Offa of Mercia and his son Ecgfrith in 796. Ceolwulf was deposed in 823 by Beornwulf, perhaps the first of the B group, who was killed fighting against the East Anglians in 826. He was followed by Ludeca, not obviously linked to any of the three groups, who was killed in battle the following year. After Ludeca's death, the first of the Wig family came to power: Wiglaf, who died in 839 or 840. Beorhtwulf, who succeeded to the throne that year, is likely to have come from the B group, which may also have included the ill-fated Beornred who "held [power] a little while and unhappily" after the murder of King Æthelbald in 757.[4]

An alternative model of Mercian succession is that a number of kin-groups may have competed for the succession. The sub-kingdoms of the Hwicce, the Tomsæte, and the unidentified Gaini are examples of such power-bases. Marriage alliances could also have played a part. Competing magnates—those called in charters "dux" or "princeps" (that is, leaders)—may have brought the kings to power. In this model, the Mercian kings are little more than leading noblemen.[4]

An important source for the period is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals in Old English narrating the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The Chronicle was a West Saxon production, however, and is sometimes thought to be biased in favour of Wessex.[5] Charters dating from Beorhtwulf's reign have survived; these were documents which granted land to followers or to churchmen and were witnessed by the kings who had the authority to grant the land.[6][7] A charter might record the names of both a subject king and his overlord on the witness list appended to the grant. Such a witness list can be seen on the Ismere Diploma, for example, where Æthelric, son of king Oshere of the Hwicce, is described as a "subregulus", or subking, of Æthelbald of Mercia.[8]

Accession and coinage

It is possible that Beorhtwulf is the same person as the Beorhtwulf who witnessed a charter of Wiglaf's in 836. If so, this is Beorhtwulf's first appearance in the historical record.[9] His accession to the throne of Mercia is usually thought to have occurred in about 840.[10] The date is not given directly in any of the primary sources, but it is known from regnal lists that he succeeded Wiglaf as king. Historian D. P. Kirby suggests that Wiglaf's death occurred in 839, basing this date on the known chronology of the reigns of Beorhtwulf and Burgred, the next two Mercian kings. It is possible that Wigmund, the son of Wiglaf, was king briefly between Wiglaf and Beorhtwulf. The evidence for this possibility comes only from a later tradition concerning Wigmund's son, Wigstan, so it is uncertain whether he actually did so.[11]

Almost no Mercian coins are known from the 830s, after Wiglaf regained Mercia from Egbert of Wessex. Beorhtwulf restarted a Mercian coinage early in his reign, and the extended gap in the 830s has led to the suggestion that Wiglaf's second reign was as a client king of Egbert's, without permission to mint his own coinage. Beorhtwulf's coinage would then indicate his independence of Mercia. However, it is more usually thought that Wiglaf took Mercia back by force. An alternative explanation for Beorhtwulf's revival of the coinage is that it was part of a plan for economic regeneration in the face of the Viking attacks. The Viking threat may also account for the evident cooperation in matters of currency between Mercia and Wessex which began in Beorhtwulf's reign and lasted until the end of the independent Mercian kingdom on the death of King Ceolwulf II in the years around 880.[12]

The earliest of Beorhtwulf's coins were issued in 841–842, and can be identified as the work of a Rochester die-cutter who also produced coins early in the reign of Æthelwulf of Wessex. After ten years without any coinage, Beorhtwulf would have had to go outside Mercia to find skilled die-cutters, and Rochester was the closest mint. Hence the link to Rochester probably does not indicate that the coins were minted there; it is more likely that they were produced in London, which was under Mercian control. Subsequent coins of Beorhtwulf's are very similar to Æthelwulf's. One coin combines a portrait of Beorhtwulf on the reverse side with a design used by Æthelwulf on the obverse; this has been interpreted as indicating an alliance between the two kingdoms, but it is more likely to have been the work of a forger or an illiterate moneyer reusing the design of a coin of Æthelwulf's. A different coinage appears later in the 840s, and was probably ended by the Viking attacks of 850–851. There are also coins without portraits that are likely to have been produced at the very end of Beorhtwulf's reign.[13][14]

Reign

Beorhtwulf's kingship began auspiciously. In the battle of Catill[15] or Cyfeiliog,[16] he killed King Merfyn Frych of Gwynedd[16] and later sources imply (see below) that he was able to subjugate the northern Welsh after this.

However, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records Viking raids in 841 against the south and east coasts of Britain, including the Mercian province of Lindsey, centred on modern Lincoln. The city of London, chief centre of Mercia's trade, was attacked the following year. The Chronicle states that there was "great slaughter" in London, and large coin hoards were buried in the city at this time.[17]

Berkshire appears to have passed out of Mercian hands and become a part of the kingdom of Wessex at some point during the late 840s. In 844 Ceolred, the bishop of Leicester, granted Beorhtwulf an estate at Pangbourne, in Berkshire, so the area was still in Mercian hands at that date. Asser, writing in about 893, believed that King Alfred the Great was born between 847 and 849 at Wantage in Berkshire. The implication is that Berkshire had previously come under the control of Wessex, though it is also possible the territory was divided between the two kingdoms, possibly even before Beorhtwulf's accession. Whatever the nature of the change, there is no record of how it occurred. It appears that the Mercian ealdorman Æthelwulf remained in office afterwards, implying a peaceful transition.[10][18][19][20][21]

In 853, not long after Beorhtwulf's death, the Welsh rebelled against Burgred and were subdued by an alliance between Burgred and Æthelwulf.[22][23]

Charters

The synod at Croft held by Wiglaf in 836, which Beorhtwulf may have attended, was the last such conclave called together by a Mercian king. During Beorhtwulf's reign and thereafter, the kingdom of Wessex had more influence than Mercia with the Archbishop of Canterbury.[10] A charter of 840 provides evidence of a different kind concerning Beorhtwulf's relations with the church. The charter concerns lands that had originally been granted by Offa to the monastery of Bredon in Worcestershire. The lands had come under the control of the church in Worcester, but Beorhtwulf had seized the land again. In the charter Beorhtwulf acknowledges the church's right to the land, but forces a handsome gift from the bishop in return: "four very choice horses and a ring of 30 mancuses and a skilfully wrought dish of three pounds, and two silver horns of four pounds ... [and] ... two good horses and two goblets of two pounds and one gilded cup of two pounds."[24] This is not an isolated case; there are other charters that show Mercian kings of the time disputing property with the church, such as a charter of 849 in which Beorhtwulf received a lease on land from the bishop of Worcester, and promised in return that he would be "more firmly the friend of the bishop and his community" and, in the words of historian Patrick Wormald, "would not rob them in future".[25] Wormald suggests that this ruthless behaviour may be explained by the fact that landed estates were becoming harder to find, as so much land had been granted to monasteries. The problem had been mentioned over a century before by Bede, who in a letter to Egbert, the Archbishop of York, had complained of "a complete lack of places where the sons of nobles and of veteran thegns can receive an estate".[26] Beorhtwulf's concession of wrongdoing suggests that he could not rely on his nobles to support him in such a disagreement, and may indicate that his hold on the throne was insecure.[21]

Holders of land were under an obligation to the king to support the king's household, though exemptions could be obtained. A charter of the late 840s released the monastery of Breedon on the Hill from the requirement to supply food and lodging to Beorhtwulf's servants and messengers, including "the royal hawks, huntsmen, horses, and their attendants". The exemption cost a substantial sum, and did not release the monastery from every burden; the obligation to feed messengers from neighbouring kingdoms or from overseas was excluded from the exemption.[27][28]

End

In 851, a Viking army landed at Thanet, then still an island, and over-wintered there. A second Viking force of 350 ships is reported by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to have stormed Canterbury and London, and to have "put to flight Beorhtwulf, king of Mercia, with his army".[23] The Vikings were defeated by Æthelwulf and his sons, Æthelstan and Æthelbald, but the economic impact appears to have been significant, as Mercian coinage in London was very limited after 851.[29]

No surviving contemporary source records Beorhtwulf's death, but according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle his successor, Burgred, reigned for twenty-two years and was driven from his throne by the Vikings in 874, implying that Beorhtwulf died in 852. From Burgred's charters it is known that his reign began before 25 July 852.[11] It has been suggested that an otherwise unknown king named Eanred may have reigned briefly between Beorhtwulf and Burgred; the evidence for this consists of a single silver penny inscribed "EANRED REX", which has similarities to some of Beorhtwulf's and Æthelwulf's pennies and hence is thought to have been produced after 850. The only recorded King Eanred ruled in Northumbria and is thought to have died in 840, though an alternative chronology of the Northumbrian kings has been proposed that would eliminate this discrepancy. Generally the penny is considered to belong to "an unknown ruler of a southern kingdom", and it cannot be assumed that an Eanred succeeded Beorhtwulf.[30][31]

Family

Beorhtwulf was married to Sæthryth, apparently a figure of some importance in her own right as she witnessed all of his charters between 840 and 849, after which she disappears from the record.[21][32] Beorhtwulf is said to have had two sons, Beorhtfrith and Beorhtric.[33] Beorhtric is known from witnessing his father's charters, but he ceased to do so before the end of Beorhtwulf's reign.[34]

The story of Beorhtwulf's other known son, Beorhtfrith, is told in the Passio sancti Wigstani, which may include material from a late 9th-century source, with some corroboration in the chronicle of John of Worcester. Beorhtfrith wished to marry the royal heiress Ælfflæd, King Ceolwulf's daughter, widow of Wiglaf's son Wigmund and mother of Wigstan. Wigstan refused to allow the marriage, since Beorhtfrith was a kinsman of Wigmund's and was also Wigstan's godfather. In revenge, Beorhtfrith murdered Wigstan, who was subsequently venerated as a saint. The story, though of late origin, is regarded as plausible by modern historians.[21][35]

Notes

- Hunter Blair, Roman Britain, p. 274.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 121.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 185

- Simon Keynes, "Mercia and Wessex in the Ninth Century", pp. 314–323; Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 119–122 & table 14. Baldred of Kent (ruled 821?–825) may have been a member of the B family. Finally, a possible East Anglian link, with King Beonna of East Anglia and the Beodric for whom Bury St Edmunds was originally named, has been mooted; Plunkett, Steven (2005), Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, Stroud: Tempus, pp. 187 & 196, ISBN 0-7524-3139-0

- Campbell, Anglo-Saxon State, p. 144.

- Hunter Blair, Roman Britain, pp. 14–15.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, pp. 95–98.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 67, pp. 453–454.

- Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England, "Beorhtwulf 3 (Male)"; Keynes, "Mercia and Wessex in the Ninth Century", p. 317.

- Zaluckyj & Zaluckyj, "Decline", pp. 238–239.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 194.

- Williams, "Mercian coinage", pp. 223–226.

- Blackburn & Grierson, Medieval European Coinage, pp. 292–293.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 195.

- The Annals of Wales (B text), p. 10.

- Chronicle of the Princes, entry 838.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pp. 62–65, Ms. A, s.a. 838 & 839, Ms. E. s.a. 837 & 839; Cowie, "Mercian London", pp. 207–208.

- Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, p. 228, note 2; Kirby, p. 195; Williams, pp. 65–66.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 234.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 87, pp. 480–481.

- Kelly, "Berhtwulf"

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 192, 195.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pp. 64–65, Ms. A, s.a. 850 & 853, Ms. E. s.a. 850 & 852.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 86, pp. 479–480. A mancus was about 4 grams (0.14 oz) of gold; see Campbell, "The East Anglian Sees Before the Conquest", p. 119.

- Wormald, "The Ninth Century", p. 139.

- Wormald, "The Ninth Century", p. 139. Wormald includes the quote from Bede, which is from chapter 11 of Bede's letter to Egbert.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 125.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 289.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 211.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 198.

- Blackburn & Grierson, Medieval European Coinage, p. 301.

- Stafford, "Political women in Mercia", pp. 42–43.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, table 14.

- Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England, "Beorhtric 2 (Male)".

- Thacker, "Kings, Saints and Monasteries", pp. 12–14; Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 194; Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 119–122. The detail of Wigmund having been king is regarded as suspect, however; see Kirby, for example.

References

Primary sources

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (1983), Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044409-2

- Swanton, Michael (1996), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-92129-5

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968), English Historical Documents v.l. c.500–1042, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode

Secondary sources

- Blackburn, Mark & Grierson, Philip, Medieval European Coinage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, reprinted with corrections 2006. ISBN 0-521-03177-X

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1966), Roman Britain and Early England: 55 B.C. – A.D. 871, W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-00361-2

- Campbell, James (2000), "The East Anglian Sees Before the Conquest", The Anglo-Saxon State, Hambledon and London, ISBN 1-85285-176-7

- Cowie, Robert (2001), "Mercian London", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.), Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 194–209, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- Hunt, William (1885). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Kelly, S.E. "Berhtwulf". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Keynes, Simon (2001), "Mercia and Wessex in the Ninth Century", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.), Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 310–328, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- Kirby, D.P. (1991), The Earliest English Kings, London: Unwin Hyman, ISBN 0-04-445691-3

- Stafford, Pauline (2001), "Political women in Mercia, Eighth to Tenth centuries", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.), Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 35–49, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- Thacker, Alan (1985), "Kings, Saints and Monasteries in Pre-Viking Mercia" (PDF), Midland History, 10: 1–25, ISSN 0047-729X, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008, retrieved 10 January 2008

- Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred; Kirby, D.P. (1991), A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain, London: Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-047-2

- Williams, Gareth (2001), "Mercian Coinage and Authority", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.), Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 210–228, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- Williams, Gareth (2001), "Military Institutions and Royal Power", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.), Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 295–309, ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- Williams, Ann (1999), Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066, Basingstoke: Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-56798-6

- Wormald, Patrick (1982), "The Ninth Century", in James Campbell; et al. (eds.), The Anglo-Saxons, London: Phaidon, pp. 132–159, ISBN 0-14-014395-5

- Yorke, Barbara (1990), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London: Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-027-8

- Zaluckyj, Sarah (2001), Mercia: the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Central England, Almeley: Logaston Press, ISBN 1-873827-62-8