Boston and Lowell Railroad

The Boston and Lowell Railroad was a railroad that operated in Massachusetts in the United States. It was one of the first railroads in North America and the first major one in the state. The line later operated as part of the Boston and Maine Railroad's Southern Division.

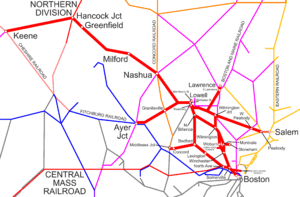

Map of the Southern Division as it was in 1887, just before it was leased by the Boston and Maine Railroad, including the original Boston to Lowell mainline | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Boston to Lowell, Massachusetts and beyond into New Hampshire and Vermont |

| Dates of operation | 1835– |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

Beginnings

In the early 19th century, Francis Cabot Lowell and his friends and colleagues established in Waltham, Massachusetts, the Boston Manufacturing Company—the first integrated textile mill in the United States. After Lowell's death in 1817, his partners searched for a new location with greater waterpower to expand textile production and add calico printing to their capabilities. In 1821 they purchased property adjoining the Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack River, an area also served by the Middlesex Canal.[1] In 1823 the Merrimack Manufacturing Company began producing cotton cloth in the "Middlesex Village" hamlet in East Chelmsford.[1]:134–141 In 1826, the area was incorporated as the town of Lowell, Massachusetts, named in honor of Francis Cabot Lowell.

The mill's problems

Before the railroad, there were several ways of moving goods between Lowell and the port of Boston warehouses. The Middlesex Canal, which opened in stages between 1804 and 1814[1]:124–135 and linked Boston with Concord, New Hampshire, was usable eight months a year, being closed during the winter months. Boating services by a variety of independent operators (called "transients" by canal management[1]) and the few big boating operators were regularly reaching towns of eastern Vermont and western New Hampshire, in the Green Mountains and White Mountains respectively, with small boats known to service towns 150 miles (240 km) from the mouth of the Merrimack.[1] Despite the innate high bulk handling advantages of canal boats, stagecoaches and cartiers' heavy-haul wagons offered competitive freight hauling rates and often competed successfully with the Middlesex Canal[lower-alpha 1] and ran effectively when the weather was dry on the road between Boston and Lowell. Large horse-drawn wagons carried freight, but along with environmental risks and delays, there were additional significant charges for carriage within the city and for unloading by stevedores, so cartage was also not ideal to get finished cloth to the dock warehouses — therein the canal boats had the edge, for they delivered directly without extra charges. These sufficed for some time, but as Lowell grew and more industrialists built mills there, problems with both modes soon motivated them to learn more of the newfangled railways that had been in the European news increasingly since 1820.

The beginning of an avalanche

The first uses of railroads in North America for heavy haulage were visible in at least three periods. A portable temporary funicular cable railway was first employed in 1795 by Charles Bulfinch, architect of the State House and other prominent Boston properties, to reshape (raze and shave) Boston's "Tri-mount" – or "the Tremont" – which were the three peaks dominating the colonial era's goosenecked peninsula's eastern and northern topography.[2]:4 The hills' summits and sides were systematically cut down at different times before 1816,[lower-alpha 2] with the first cuttings occurring in 1795 to build the Massachusetts State House on Beacon Hill at a more desirable lower elevation. Fredrick Gamst believes the same hardware was then relocated and used again in 1799–1804 and 1809–1815 to transfer hilltop materials into land reclamation and real-estate speculation, that began creating Boston's famed Back Bay neighborhoods from the long mud flats of the Charles River by creation of the duck pond and public gardens near the Boston Common.

The second operational and chartered "meant to be permanent" railway in the country[lower-alpha 3] was the Granite Railroad, chartered and built in 1826 in nearby Quincy. It was a 3-mile (5 km), horse-powered railroad, built to move large granite stones from the quarries in Quincy to the Neponset River in Milton. As was believed to be the most sturdy method at the time, it was built on a deep foundation of granite, setting a precedent for all railroads that could afford it.

1824–1826 brought news of multiple charter applications and grants for a variety of canal and turnpike and rail projects in the eastern and near midwestern states, then early March 1827 brought electric news to American financial markets: word that rails were being laid on the 9-mile (14 km) wagon road's mountain descent from the anthracite mines at Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, to the Lehigh Canal at Mauch Chunk by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company — conversion of a well-known engineering marvel into a railroad. The project was engineered by Josiah White and superintended by Erskine Hazard, whose towering reputations[3] as the two men who had both shown how[4] to end the energy crises, and provided the means to do so, almost immediately made railway systems credible; they became transport solutions to be considered seriously within investor circles.

During the summer of 1827,[lower-alpha 5] a railroad was built from the mines at Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk. With one or two unimportant exceptions, this was the first railroad in the United States.

— James E. Held, Archaeology[6]

The canal was a very efficient way of moving large amounts of heavy goods cheaply and with minimal labor. But White and Hazard had single-handedly spurred canal construction up and down the East Coast by taming the Lehigh River with navigations in less than two years, and four years ahead of promises to investors. Unfortunately, the northern canals would freeze in the winter, and their towpaths were muddy in spring and late fall. This made it impractical for a burgeoning mill town that needed year-round freight transportation, but if LC&N Co. was putting monies into railroads, other businessmen were going to have to take a hard careful look. With steamboat tugs proven on the Merrimack and Middlesex Canal themselves, and news of railroads building in Europe and now, the United States, investors would need to adopt new techniques sooner or miss opportunities.

Stagecoaches provided the passenger aspect of the transport, moving 100 to 120 passengers per day. There were six stagecoaches in operation at the time of the building of the railroad, for a total of 39 fully loaded round trips per week. This was sufficient passenger service for people who had to make an occasional trip but was much too expensive for daily use or what we would now call commuting.

The investors in the Lowell textile companies decided they needed to do something about their transportation situation. They looked toward the railroads budding in England, and now in America, for inspiration and took operations on the Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk Railroad and the construction ongoing on the Allegheny Portage Railroad and Baltimore & Ohio and a handful of other ventures as omens and inspiration. A railroad could run year round, was expandable with as many tracks as they might need, and could use the new locomotives that were being highly praised in England at the heart of recent news stories. By 1829 the B&O was testing a locally produced steam locomotive, the Tom Thumb, and opened for passenger operations in May 1830. With well-publicized and ambitious plans to scale one of the gaps of the Allegheny and cross the Ohio River, and New York and Pennsylvania's canal mania sprinkled with railroads, Massachusetts and New England investors were looking at bold plans everywhere.

Charter

Patrick Tracy Jackson led the task of convincing the state legislature to fund the project. This proved difficult, as the investors of the Middlesex Canal were against building a new form of transportation designed to replace their canal.

Because, prior to 1872, there was no provision in Massachusetts state law for chartering railroads, all had to be chartered by special acts of legislature. This made it slow and inefficient to charter a railroad because the politicians had to agree; the issue would become partisan. This also meant that the legislature would not let the investors build the line unless they could show it was completely necessary.

The investors were successful because they convinced the legislature that the canal was inherently incapable of providing what they needed: reliable, year-round freight transport. Investors in the Boston and Lowell Railroad received a charter on June 5, 1830, with no provision for reparations to the Middlesex Canal's investors. It was a favorable charter because in addition to the right to build and operate a railroad between Lowell and Boston, it gave a thirty-year monopoly on the right to have a railroad there. The people along the road and in terminal-end cities bought large amounts of stock, financing half the company.

Construction

The Board of Directors of the Boston and Lowell Railroad, armed with a charter, now had the task of surveying and building the line. They brought in James Fowle Baldwin, son of Col. Loammi Baldwin, who had engineered the Middlesex Canal, to do the surveying, and charged him with finding a gently sloped path from Lowell to Boston, with few grade crossings and well away from town centers. This latter point ended up being quite inconvenient later on. No one had any idea of the future possibility of railroads acting as public transportation, or if they did they were not paid any attention by the builders or financiers of the road.

The right-of-way that Baldwin surveyed did well in each of these characteristics. The path sloped up at a gentle ten feet per mile at the maximum, and there were only three grade crossings over the entire 26-mile (42 km) distance. The path was close to the older Middlesex Canal path, but was straighter - as boats can turn more sharply than trains. To achieve this superior linearity, it needed small amounts of grade elevation in places. The route ignored Medford center entirely, going through West Medford instead, and totally bypassed Woburn and Billerica. This would have to be corrected later with various spurs (the one to Medford being built off the Boston and Maine Railroad), but were always sources of annoyance to both riders and operators.

The proposed route was accepted by the Board of Directors of the Boston and Lowell Railroad, and work began on the building phase. The road was begun from both ends at once, and some sources say that they both started on the right hand side of the right-of-way, missing in the middle and having to put in an embarrassing reverse curve to tide them over until they built the other side. Yankee and Irish laborers were hired to construct the railroad, which was made especially difficult and because the Directors wanted to make the road using the best techniques then known. This, for them, meant laying imported British iron rails with a 4-foot-deep (1.2 m) wall of granite under each rail. They did this because it was commonly believed that the train would sink into the ground if the rails did not have strong support.

The first track was completed in 1835, and freight service began immediately. On May 27, 1835, it made its maiden trip to Boston, with Patrick Tracy Jackson, George Washington Whistler, and James Baldwin aboard.[7] The solid granite roadbed proved to be much too rigid, jolting the engine and cars nearly to pieces. Repairs on the locomotives (there were two at the time) would sometimes take most of the night, trying to get them ready for the next day's service. The much poorer Boston and Worcester Railroad could not afford a granite bed and so was built with modern wooden ties. This turned out to be far superior, so the owners of the Boston and Lowell decided they would upgrade their entire roadbed to wood when they added a second track.

The original Boston terminal was at the north corner of Causeway Street and Andover Street (halfway between Portland and Friend streets), at the westernmost edge of the current North Station. The bridge over the Charles River to access it was the first movable railroad bridge in the United States. The original Lowell terminal was at the south corner of Merrimack Street and Dutton Street.

Early operation

The quantity of freight traffic on the Boston and Lowell Railroad was large from the start (as was expected) with Lowell's textile companies bringing in raw materials and sending out finished goods. The high level of passenger traffic, however, was not anticipated.[8]:92 Trains traveled on unwelded rails which were laid on a granite roadbed, which made for an extremely bumpy ride. The railroad switched to wooden ties.[8]:84

The Boston and Lowell was faced with a new problem; it had a reputation for speed which made it very popular and highly competitive with stagecoaches. Many people wanted to go not only from Lowell to Boston but to places in between. The Boston and Lowell ordered another locomotive and cars for local passenger rail in 1842, and had them make six stops along the route. Passenger rail proved to be almost as profitable as freight.[9]

Locomotives

The first locomotives on the B&L were copies of the successful Planet class 2-2-0 built locally in Lowell.[10]

The Boston and Maine Railroad

Another railroad was chartered in the early 1840s whose fortunes would be closely tied to those of the Boston and Lowell. This was the Boston and Maine Railroad. This railroad ran down from Portland, Maine, through a bit of southern New Hampshire, to Haverhill in northeastern Massachusetts, connected to the Boston and Lowell in Wilmington, and then used Boston and Lowell track to Boston. This route was conceptualized in 1834, but took a long time to be built, mostly because, unlike the Boston and Lowell, it did not have a secure base of funding like the Lowell textile companies. It took two years to get to Andover, another year to get to Haverhill, three more to get to Exeter, New Hampshire, and did not get to Portland until 1852.

This extra traffic on the Boston and Lowell Railroad, especially with the line still over granite, provided the extra impetus to double track and upgrade. In 1838, the B&L began two years of extensive track improvements, first laying a second track on wood, and with that one built, going back and re-laying the old track on the more forgiving wood as well. Boston and Lowell traffic continued to increase, and even with double tracks the schedule became tight enough that the Boston and Maine trains, as renters, began to be pushed around to annoying hours, often having to wait over an hour in Wilmington before being allowed to proceed on to Boston.

The B&M soon tired of what they perceived as selfishness and decided to build its own track to Boston from Haverhill so that it would not have to rely on the B&L. The B&L tried to fight the B&M in court but failed because the monopoly granted in its charter was only good for traffic between Boston and Lowell. The shortcut, part of today's Haverhill/Reading Line, was started in 1844 and was in use by 1848. While the B&M was building it, they were still running their trains to Boston on the B&L. This made for a lot of conflict, with the B&L trying to squeeze every last penny out of the B&M before it lost the opportunity. The B&M tried to deal with this in court, and got the judge to forbid the B&L from raising rates until the case was done, but by the time they were close to an agreement, the bypass was complete.

With B&M business gone, the B&L realized how much they had been relying upon their renters. Additionally, the Lowell mills began to decline somewhat and there was less freight traffic for the line to move. Over the next four decades, the B&L declined until the more successful B&M leased it on April 1, 1887.

Branches

The B&L built or leased many branches to serve areas not on its original line. Immediately before its lease by the B&M in 1887, it had five divisions—the Southern Division (including the original line), the Northern Division, the White Mountains Division, the Vermont Division, and the Passumpsic Division. Additionally, it leased the Central Massachusetts Railroad in 1886.

Southern Division

The main part of the Southern Division was the mainline between Boston and Lowell.

- Charlestown

The Charlestown Branch Railroad was not itself taken over by the B&L, but as originally built in 1840 it was a short spur from the B&L to wharves in Charlestown. In 1845 the Fitchburg Railroad leased it and incorporated it into their main line.

- Mystic River

The Mystic River Branch served the Mystic River waterfront on the north side of Charlestown.

- Woburn Loop

The Woburn Branch Railroad (aka the Woburn Loop) opened in 1844, connecting Woburn to the main line towards Boston. The Horn Pond Branch Railroad was a short freight-only branch off the Woburn Branch to ice houses on Horn Pond. The northern loop, built in 1885, continued the line back north to the main line at North Woburn Jct. in South Wilmington. The Horn Pond branch line was abandoned in 1911, the northern loop in 1961, and the original line in 1982.

- Stoneham

The Stoneham Branch Railroad was built in 1862 to connect to Stoneham.

- Lowell and Lawrence

The Lowell and Lawrence Railroad was chartered in 1846 to build a line between Lowell and Lawrence, which opened in 1848. In 1858 the B&L leased the line.

- Salem and Lowell

The Salem and Lowell Railroad was chartered in 1848 as a branch from the Lowell and Lawrence at Tewksbury Junction to the Essex Railroad at Peabody, along which it used trackage rights to Salem. The line was opened in 1850 and operated by the Lowell and Lawrence until 1858, when the B&L leased it along with the Lowell and Lawrence.

- Wilmington (Wildcat) Branch

The Wilmington Branch, now known as the Wildcat Branch, was built just west of the original Boston and Maine Railroad alignment to connect the main line at Wilmington to the Salem and Lowell at Wilmington Junction, providing a shorter route between Boston and Lawrence.

- Lexington and Arlington (Middlesex Central Railroad)

The Lexington and West Cambridge Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened in 1846, connecting the Fitchburg Railroad at West Cambridge to Lexington, although the "West Cambridge" in the name referred to what is now the town of Arlington. It was operated by the Fitchburg from opening, and leased to the Fitchburg from 1847 to 1859. The line was reorganized as the Lexington and Arlington Railroad in 1868, following the renaming of Arlington. The B&L bought the line in 1870 and built a new connection to their main line at Somerville Junction.

The Middlesex Central Railroad was chartered in 1872 and opened in 1873, extending the line from Lexington to Concord. It was leased from completion to the B&L. An extension west to the Nashua, Acton and Boston Railroad at Middlesex Junction was built in 1879.[11]

- Billerica and Bedford

The Billerica and Bedford Railroad was built in 1877 as a narrow gauge line between the Middlesex Central at Bedford and the B&L at North Billerica. It was sold and abandoned in 1878, and the rails were taken to Maine for the Sandy River Railroad. A new standard gauge branch was built by the B&L in 1885, mostly on the same right-of-way.[11]

- Lowell and Nashua

The Lowell and Nashua Railroad was chartered in 1836 as an extension of the B&L from Lowell north to the New Hampshire state line. The Nashua and Lowell Railroad, chartered in 1835, would continue the line in New Hampshire to Nashua. The two companies merged in 1838 to form a new Nashua and Lowell Railroad, and the road opened later that year. In 1857 the B&L and N&L agreed to operate as one company from 1860, and in 1880 the B&L leased the N&L.

- Stony Brook

The Stony Brook Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened in 1848, connecting the Nashua and Lowell at North Chelmsford with Ayer. The N&L leased the Stony Brook in 1848.

- Nashua to Keene

The Wilton Railroad was chartered in 1844. It opened a line from Nashua west to Danforth's Corner in 1848, to Milford in 1850 and to East Wilton in 1851. Since completion it was operated by the N&L.

The Peterborough Railroad was chartered in 1866 to continue the Wilton Railroad northwest to Greenfield, New Hampshire. In 1873 the N&L leased it; the road opened in 1874.

The Manchester and Keene Railroad was chartered in 1864 and opened in 1878, continuing the Peterborough Railroad west from Greenfield to the Connecticut River Railroad in Keene. In 1880 the company went bankrupt, and it was operated by the Connecticut River Railroad until 1882, when it was bought half-and-half by the B&L and the Concord Railroad.

Other divisions

- Central Massachusetts Railroad

The Massachusetts Central Railroad was chartered in 1869 to build a line east-west across the middle of the state, between the Boston and Albany Railroad and the Fitchburg Railroad. The first section opened in 1881, splitting from the B&L's Lexington and Arlington Branch at North Cambridge Junction, and the company was reorganized as the Central Massachusetts Railroad in 1883. The B&L leased the line in 1886, a year before the B&M leased the B&L.

- Northern Division

The Boston, Concord and Montreal Railroad was chartered in 1844, and opened in stages from 1848 to 1853, eventually running from Concord to Woodsville, New Hampshire. That railroad, along with its branches, became part of the B&L Northern Division in 1884, when the B&L leased the BC&M.

The Northern Railroad was also chartered in 1844, opening in 1847 from Concord to Lebanon, New Hampshire, and later extending to White River Junction, Vermont. The B&L leased it in 1884 as another part of its Northern Division.

The only connection between the Southern and Northern divisions was at Hancock Junction, where the Manchester and Keene Railroad (Southern) and Peterborough and Hillsborough Railroad (Northern) met.

In 1889 the BC&M merged with the Concord Railroad to form the Concord and Montreal Railroad, taking it out of B&M control until 1895, when the B&M leased the C&M.

- White Mountains Division

The White Mountains Railroad was chartered in 1848 and opened a line from Woodsville to Littleton, New Hampshire, in 1853. Along with extensions and branches, it was leased to the Boston, Concord and Montreal Railroad in 1859 and consolidated into it in 1872, becoming its White Mountains Division. In 1884 the B&L leased the BC&M and the old White Mountains Railroad became the B&L's White Mountains Division.

The Northern and White Mountains Divisions were connected at Woodsville.

- Vermont Division

The Essex County Railroad (chartered 1864), Montpelier and St. Johnsbury Railroad (chartered 1866) and Lamoille Valley Railroad (chartered 1867) were consolidated into the Portland and Ogdensburg Railroad in 1875 as their Vermont Division. The line was finished in 1877, and in 1880 it was reorganized as the St. Johnsbury and Lake Champlain Railroad, which was taken over by the B&L as their Vermont Division. The line did not stay in the B&M system, and the easternmost part was leased to the Maine Central Railroad in 1912.

The White Mountains and Vermont Divisions were connected at Scott's Mills, New Hampshire.

- Passumpsic Division

The Connecticut and Passumpsic Rivers Railroad was organized in 1846 and opened a line from White River Junction on the Northern Railroad to the border with Quebec, Canada, in 1867, junctioning the Northern and White Mountains Divisions at Wells River and the Vermont Division at St. Johnsbury. The Massawippi Valley Railway, leased in 1870, continued to Sherbrooke, Quebec, where it junctioned the Grand Trunk Railway among others. The B&L leased the line on January 1, 1887, three months before the B&M acquired the B&L.

Life as a B&M line

Over the next 70 years or so, things were reasonably stable and constant for the Lowell Line as a part of the B&M's Southern Division. Passenger train round trips per day hovered in the low 20s, and while freight from Lowell itself did not last too long, the Lowell line got some traffic from railroads that connected from the west.

Modern times

In the early 20th century the economics of railroading began to change. With the advent of the internal combustion engine, trains slowly began to lose their advantage as a transportation option. Automobiles and trucks began to increase in popularity as highways improved, siphoning ridership and freight traffic off railroads. The advent of the Interstate Highway System tipped the economic balance by increasing mobility as factories and offices were now able to be located further away from the fixed routes of the railroads. The decline in both passenger and freight traffic occurred at a point when the B&M, like most other railroads, had just switched over to diesel locomotives, meaning that they had large debts. The pressure from the debts and the large infrastructure costs associated with operating a disparate passenger and freight network amongst declining traffic forced the B&M to cut costs. The most noticeable effect to the general public was the reductions in passenger operation. In the late 1950s the B&M began to eliminate routes and substituted Multi-Unit diesel-powered passenger cars on many of its routes. The effort did not succeed, as the B&M was bankrupt by 1976.

As its fortunes declined, the B&M shed its passenger operation in 1973 by selling the assets to the MBTA. The new state agency bought the Lowell line, along with the Haverhill and all other commuter operations in the Greater Boston area. Along with the sale, the B&M contracted to run the passenger service on the Lowell line for the MBTA. After bankruptcy, the B&M continued to run and fulfill its commuter rail contract under the protection of the Federal Bankruptcy Court, in the hopes that a reorganization could make it profitable again. It emerged from the court's protection when newly formed Guilford Transportation Industries (GTI) bought it in 1983.

When GTI bought the B&M, commuter rail service was in jeopardy. The MBTA had owned the trains and the tracks since 1973, but it had outsourced the operation to the B&M. When GTI bought the B&M in 1983, it had to honor the B&M contract, but GTI management was very much against passenger rail, and, in 1986, as soon as the contract expired, they let the job go to Amtrak.

From 1986 until 2003, Amtrak managed the entirety of Boston's commuter rail. It did decently, though at times had strained relations with the MBTA. Quibbles centered on equipment failures, numbers of conductors per train, and who took responsibility when trains are late. Because of these bad relations and Amtrak's repeated announcements that the contract was unreasonable, few people were surprised at Amtrak's decision not to bid again for the commuter rail contract when it came up for renewal in 2003.

When the MBTA asked for new bids on the commuter rail operation contract, Amtrak did not bid, but Guilford and the Massachusetts Bay Commuter Railroad Company did. The MBCR ended up getting the contract and began operating the commuter rail in July 2004.

Guilford's main line between Mattawamkeag, Maine, and Mechanicville, New York, now uses the Stony Brook Branch and the old main line north of Lowell. At Lowell it shifts to the B&M's original Lowell Branch to get to the B&M main line towards Maine.

During the years since B&M bankruptcy, highway congestion has increased significantly, resulting in growing demand for passenger and freight options. During this time frame, the MBTA has been slowly investing in some infrastructure changes in its rail operations. In 1995 a new North Station was opened. In 2001 it opened the Anderson Regional Transportation Center on the Boston & Lowell to centralize ridership and provide a superstation with convenient access to Interstates 93 and 95 (Route 128). In southern Maine, frustration with bus service drove the state to explore restarting passenger service, resulting in contracting with Amtrak to operate the Downeaster, which runs from North Station to Haverhill and up to Portland. Due to scheduling conflicts with the MBTA, the Downeaster runs up the Lowell Line to Wilmington and then out the old B&M Wildcat Branch to the Haverhill/Reading Line. This route allows the Downeaster to pass a commuter train on the Haverhill/Reading Line without schedule conflicts. The route is also historically significant because it is the same route that the original B&M used to Portland.

Station listing

| Milepost | City | Station | Opened | Closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | Boston | North Station | 1893 | Replaced original terminal on Nashua Street. | |

| 0.8 | Boston Engine Terminal | A flag stop for railroad employees only. | |||

| 0.9 | Cambridge | East Cambridge | 1927 | Closed when North Station approaches were realigned | |

| 1.8 | Somerville | Prospect Hill | 1835 | 1927 | Originally Milk Row; closed when North Station approaches were realigned |

| 2.4 | Winter Hill | 1835 | c. 1930s | Formerly Taylors Ledge and Somerville Center | |

| 2.8 | Somerville Junction | c. 1940s | Originally Somerville. Junction with Lexington and Arlington Branch. | ||

| 3.6 | North Somerville | May 18, 1958 | Formerly Cambridge Road and Willows Bridge | ||

| 4.0 | Medford | Tufts University | c. 1889

September 15, 1977 |

May 18, 1958

October, 1979 |

Formerly Stearns Steps, College Hill, and Tufts College |

| 4.6 | Medford Hillside | May 18, 1958 | Formerly Medford and Medford Steps | ||

| 5.5 | West Medford | Originally Medford Gates | |||

| 7.3 | Winchester | Wedgemere | c. 1850 | Previously called Mystic, Bacons Bridge, and Symmes Bridge | |

| 7.8 | Winchester Center | Junction with Woburn Branch. Originally South Woburn. | |||

| 9.0 | Winchester Highlands | June 1978 | Originally Winchester Heights | ||

| 9.8 | Woburn | Montvale | Junction with Stoneham Branch; originally East Woburn. | ||

| 10.5 | Walnut Hill | January 17, 1965 | Originally Woburn and Water Place | ||

| 10.9 | Lechmere Warehouse | 1979 | 1996 | ||

| 11.6 | Mishawum | September 24, 1984 | Originally North Woburn | ||

| 12.7 | Anderson/Woburn | April 28, 2001 | Former station was South Wilmington | ||

| 13.9 | Wilmington | North Woburn Junction | Junction with Woburn Branch (never a station) | ||

| 15.2 | Wilmington | c. 1836 | Junction with Wildcat Branch | ||

| 17.0 | Silver Lake | June 27, 1965 | |||

| 19.2 | Billerica | East Billerica | June 27, 1965 | Originally Billerica & Tewksbury | |

| 21.8 | North Billerica | Junction with Billerica and Bedford Branch. Originally Billerica Mills. | |||

| 23.3 | Lowell | South Lowell | 1932[12][13] | ||

| 24.6 | Bleachery | Junction with Lowell and Lawrence Railroad, Lowell Branch (B&M), and Framingham and Lowell Railroad (NYNH&H) | |||

| 25.3 | Lowell | Junction with Nashua and Lowell Railroad; formerly called Middlesex Street | |||

| 26.0 | Merrimack Street | 1905 |

Notes

- Wagon haulage was competitive to canal rates to the point the canal directors repeatedly adjusted their fee structure each year[1]:141 and conducted new studies. By the early 1820s their fee structure was stabilized and the Harvard study shows they changed little thereafter. The close accounting research showed the mill owners were systematically playing the cartiers off against the canal operation, leading the canal to create a new class of goods for finished cloth at a reduced rate to bulk freight tonnage fees. This was successful in nailing the fabric business — but could not overcome the seasonality problems, nor occasional outages from flood breaks in the canal's services. These remained to be viewed negatively by mill owners.

- The hills' summits and sides were systematically razed and cut down at different times before 1816 and after. When systematic excavations were stopped is unknown. Whether it has fully stopped is also inexact, for it can be said every foundation hole dug contributed to relocation, so building up new land. What can be said is landfill to create lots for land speculators to sell has long ceased to be ongoing. There is 1840s-'50s photographic evidence documenting that the land reclamation (creation) projects went on for decades, fill being brought in by other railways for some decades to fill the Back Bay and Brookline (west of the public gardens) well past the Civil War and Reconstruction years.

- The first chartered, the Leiper Railroad in Philadelphia,[2] was a railway resorted to when the owner could not get a charter to build a canal over the same 3-mile (4.8 km) distance, and like the Granite Railroad was a quarry railroad destined to become part of a longer, larger common carrier railroad.

- Brenckman's history of Carbon County

- "Summer of 1827" should be taken as a turn of phrase for the sake of simplification in an article focused on a wider topic – the American Canal Age. The prepositional phrase should have read "by the Summer of 1827", as the literal reading ignores the intent to be ready before the seasonal melt hazards gave way to a summer canal season. A literal interpretation is in direct conflict with highly detailed account by Brenckman and other more local (and more contemporary) historians.[3] Brenckman's account details the stockpiling of wood, iron, tools and materials over the entire preceding winter and fall. Work commenced as soon as thawing soil allowed workers to lay sleepers in March and April, with the aim of not affecting coal deliveries to the canal head, so it could resume operations as soon as ice and flooding permitted. Further, framework, couplings, tires and other iron castings were carried out in the LC&N Co.'s own foundries in Mauch Chunk, the company having financed at least eight of the first ten blast furnaces north of Easton,[lower-alpha 4] so triggering the iron and steel industries of Bethlehem and Allentown, Pennsylvania, south of the Blue Mountain escarpment. In his account of White and Hazard's attempt to smelt iron in Mauch Chunk from the late 1820s-middle 1830s Brenckman accounts for two of the first blast furnaces in Pennsylvania. LC&NC records with the state department account their costs.[5]

References

- Roberts, Christopher (1938). The Middlesex Canal 1793-1860. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, Harvard Economic Studies, Volume LXI, 386 R.

- Frederick C. Gamst, University of Massachusetts, Boston. The Transfer of Pioneering British Railroad Technology to North America. Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum, Copyright © 2004 CPRR.org. [Last updated 11/13/2004].CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fred Brenckman, Official Commonwealth Historian (1884). HISTORY OF CARBON COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA (2nd (1913) ed.). Also Containing a Separate Account of the Several Boroughs and Townships in the County, J. Nungesser, Harrisburg, PA ([archive.org/details/historyofcarbonc00inbren Archive.org project 1913 edition, pdf e-reprint]). p. 627.

- Bartholomew, Ann M.; Metz, Lance E.; Kneis, Michael (1989). Delaware and Lehigh Canals (First ed.). Oak Printing Company, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Center for Canal History and Technology, Hugh Moore Historical Park and Museum, Inc., Easton, Pennsylvania. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0930973097. LCCN 89-25150.

- Samuel Thomas, Catasauqua, PA (1899). Address delivered California meeting 1899, republished from Advanced Sheets of Vol. XXIX of the Transactions (ed.). "Early Anthracite-Iron Industry". American Institute of Mining Engineers.

(with illustrations)

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - James E. Held (July 1, 1998). "The Canal Age". Archaeology (online). A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America (July 1, 1998). Retrieved 2016-06-12.

During the summer of 1827, a railroad was built from the mines at Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk. With one or two unimportant exceptions, this was the first railroad in the United States.

- Schexnayder, Cliff (2015). Builders of the Hoosac Tunnel. Peter E. Randall Publisher. ISBN 9781942155089.

- Harlow, Alvin Fay (1946). Steelways of New England. Creative Age Press.

- Stacey, Barbara. "FAQs". www.rta.org. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-11. Retrieved 2012-04-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Boston & Maine asks right to abandon three stations". Boston Daily Globe. April 21, 1932. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "B. & M. is granted right to abandon four stations". Boston Daily Globe. June 25, 1932. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- Wall & Gray. 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts. Map of Massachusetts. USA. New England. Counties - Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Essex and Norfolk, Boston - Suffolk,Plymouth, Bristol, Barnstable and Dukes (Cape Cod). Cities - Springfield, Worcester, Lowell, Lawrence, Haverhill, Newburyport, Salem, Lynn, Taunton, Fall River. New Bedford. These 1871 maps of the Counties and Cities are useful to see the extent and names of the rail lines.

- Beers, D.G. 1872 Atlas of Essex County Map of Massachusetts Plate 5. Click on the map for a very large image. This map and the 1871 map of Middlesex County shows the original Boston and Lowell Railroad route through Billerica, Wilmington, Woburn, Winchester, and Medford. It also show the slightly later competing track of the Boston and Maine Railroad through Andover, Reading, Wakefield, Melrose, and Malden. The Wildcat Branch connector in Wilmington is shown in the 1872 maps but not the 1871 map. Also see detailed map of 1872 Essex County Plate 7.

- Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district (PDF)

- Railroad History Database

- 1886 Boston and Lowell Railroad Map

External links

Archives and records

- Nashua & Lowell Railroad records at Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School.