Boscobel (mansion)

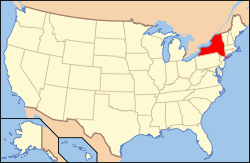

Boscobel is a historic house museum in Garrison, New York, overlooking the Hudson River. The house was built in the early 19th century by States Dyckman. It is considered an significant example of the Federal style of American architecture, augmented by Dyckman's extensive collection of period decorations and furniture.

Boscobel | |

Boscobel front facade, 2017 | |

| Location | Garrison, New York |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Beacon |

| Coordinates | 41°24′40″N 73°56′21″W |

| Area | 45 acres (18 ha) |

| Built | 1804-1808[1] |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000971 |

| Added to NRHP | 1977 |

It was originally located in the Westchester County village of Montrose. Restoration efforts in the mid-20th century moved it 15 miles (24 km) upriver to where it currently stands, on New York State Route 9D a mile south of the village of Cold Spring in Putnam County.

House

Boscobel's distinguishing feature is the unusual delicacy conveyed by the front facade and its ornamentation. Unique among Federal style buildings, carved wooden swags in the shape of drapery, complete with tassels and bowknots, grace the top of the second-story balcony. Nearly one-third of the face is glass, with flanking lights integrated into contemporary windows used in the restoration to enhance the effect. The windows are slightly recessed, and the front clapboards are closely fitted and matched in an apparent effort to suggest masonry.[2]

Some alterations during the relocation and reconstruction include the rear entrance and stairway, required by contemporary fire code, were added in 1958 during, and a former dirt-floored room in the basement was turned into a visitors' bathroom.[3]

Adjacent to the house is a permanent sculpture garden with ten bronze busts of significant Hudson River School artists.[4] The work of Greg Wyatt, director of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation Academy of Art, they were donated by the foundation. Boscobel was chosen because of its location in the Hudson Highlands, a popular subject of the school's painters, and rough geographic center of Hudson River School artist homes and the landscapes that they painted.[5]

History

Construction

States Dyckman, a descendant of early Dutch settlers of Manhattan, had managed to retain his family fortune despite being an active Loyalist and working in the British Army's Quartermaster Corps for most of the war, keeping the accounts of various quartermasters. When Sir William Erskine, Quartermaster General, returned to England in 1779 to face an audit and investigation for war profiteering, he asked Dyckman to accompany him. He remained in England ten years, participating in other investigations of quartermasters and only returned to the newly independent United States in 1789.[1]

While in London he associated with many wealthy members of society and acquired their tastes, particularly for the neoclassical buildings of Robert Adam. He bought many furnishings and decorative objects, such as a Wedgwood dinner service, and had them shipped back to the United States with him.[3] With the interest on a sizable life annuity granted him by Sir William Erskine, Dyckman intended to build an estate on 250 acres (1 km²) near Montrose and named it Boscobel, perhaps after Boscobel House in Shropshire (itself named for the Italianate bosco bello, "pretty woodland"), symbolizing his Anglophilia.[6] According to one biographer, he saw himself as a "conspicuously well-fixed farmer, surrounded with objects of taste...who did not farm too seriously".[1] He began this process by marrying Elizabeth Corne, daughter of another Loyalist family, in 1794. But within a year he faced financial difficulties, the halt of Erskine's annuity by his heirs after his death and his own lavish tastes and generous gifts to less fortunate family members contributing to reduce his circumstances.

Dyckman returned to London in 1799, expecting to mend his fortunes and return to his wife, son and daughter within a year.[1] Instead he remained three years, finishing the remaining quartermasters' investigation under John Dalrymple, himself once one of the inquiry's targets. He restored his fortunes by persuading the Erskines to restore their annuity and negotiating an extremely generous settlement with Dalrymple and the other quartermasters whom he had helped clear, apparently by manipulating evidence.[1]

Wealthier but injured and ailing, Dyckman returned to the United States in 1803 and set about building the house he had long planned. It is possible that he had blueprints drawn up in England, since work began within six months of his return.[3] The architect is not known, although surviving records show that a William Vermilye was heavily involved as construction manager.[3] Dyckman died in 1806, before it was finished. His widow completed it, and she and their surviving son moved into it in 1808.

Restoration

The family retained ownership of the house until 1920. For the next 35 years, under subsequent owners, it frequently faced the possibility of being demolished. In 1955 an organization called Friends of Boscobel saved it from a contractor who had bid $35 to knock it down after the Veterans' Administration had built a hospital on the site. They arranged for it to be moved to a similar location upriver, near Cold Spring, a year later,[2] using photographs from the Historic American Buildings Survey to guide the reconstruction.[3]

Lila Acheson Wallace, co-founder of Reader's Digest, had at first anonymously provided the $50,000 donation to make the move and reconstruction possible. As Friends of Boscobel became Boscobel Restoration, Inc., she took a more public role as a director particularly in overseeing the landscaping and interior decoration.[2] Richard K. Webel designed grounds for the new site that bore little resemblance to its original surroundings, favoring the "country house" style popular in the early 20th century. Large grown trees were planted to give the impression that the house had always been there.[7]

The rebuilt home was formally reopened on May 21, 1961, at a ceremony attended by then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who praised it as "one of the most beautiful homes ever built in America". Lila Acheson Wallace later spearheaded the development of a 40-minute sound and light show on the grounds, which ran twice a week in summers until the late 1970s. Around that time, new papers of Dyckman's were discovered, and the house was closed for six months in 1977 while it was redecorated in a manner more consistent with his recorded tastes. It opened again that summer to high praise.[7]

Tours

The house is open every day of the week (except Tuesdays and holidays) from April through December. The second Tuesday of each month is set aside to allow artists free entry to paint or sketch on the grounds. Visitors are allowed to picnic on the grounds.[8] The Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival performs under a tent during the summer months.[9]

References

Notes

- Lyle, Charles (2003). "Boscobel History". Archived from the original on 2008-01-21. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- Lyle, Charles (2003). "Boscobel History, Continued". Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- Gobrecht, L. E. (February 1977). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Boscobel". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- "Boscobel House and Gardens: 2016 Annual Report" (PDF). Boscobel House and Gardens. 2016. p. 4. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Deffenbaugh, Ryan (September 2017). "Boscobel Sculptures Capture Hudson River School". Wag Magazine. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Faber, Harold (March 3, 1991). "Sunday Outing; Worth $35 to a Wrecker, Boscobel Is Now a Gem". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- Lyle, Charles (2003). "Boscobel History, Continued, Page 3". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- "Boscobel Admission and Hours". Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- "Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival 2008 Season". Archived from the original on 2008-01-21. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

Further reading

- Great Houses of the Hudson River, Michael Middleton Dwyer, editor, with preface by Mark Rockefeller, Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, published in association with Historic Hudson Valley, 2001. ISBN 0-8212-2767-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boscobel (mansion). |

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-5667, "Boscobel, State Route 9D, Garrison, Putnam County, NY", 28 measured drawings