Blind Lemon Jefferson

Lemon Henry "Blind Lemon" Jefferson (September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929)[8] was an American blues and gospel singer-songwriter and musician. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s and has been called the "Father of the Texas Blues".[9]

Blind Lemon Jefferson | |

|---|---|

Only known photograph of Jefferson, 1926 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Lemon Henry Jefferson |

| Born | September 24, 1893 Coutchman, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | December 19, 1929 (aged 36) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1912–1929[7] |

Jefferson's performances were distinctive because of his high-pitched voice and the originality of his guitar playing.[9] His recordings sold well, but he was not a strong influence on younger blues singers of his generation, who could not imitate him as easily as they could other commercially successful artists.[10] Later blues and rock and roll musicians, however, did attempt to imitate both his songs and his musical style.[9]

Biography

Early life

Jefferson was born blind, near Coutchman, Texas. He was the youngest of seven[11] (or possibly eight) children born to Alex and Clarissa Jefferson, who were African-American sharecroppers.[9] Disputes regarding the date of his birth derive from contradictory census records and draft registration records. By 1900, the family was farming southeast of Streetman, Texas. Jefferson's birth date was recorded as September 1893 in the 1900 census.[12] The 1910 census, taken in May, before his birthday, confirms his year of birth as 1893 and indicated that the family was farming northwest of Wortham, near his birthplace.[13]

In his 1917 draft registration, Jefferson gave his birthday as October 26, 1894, stating that he lived in Dallas, Texas, and had been blind since birth.[14] In the 1920 census, he is recorded as having returned to Freestone County and was living with his half-brother, Kit Banks, on a farm between Wortham and Streetman.[15]

Jefferson began playing the guitar in his early teens and soon after he began performing at picnics and parties. He became a street musician, playing in East Texas towns in front of barbershops and on street corners.[9] According to his cousin Alec Jefferson, quoted in the notes for Blind Lemon Jefferson, Classic Sides:

They were rough. Men were hustling women and selling bootleg and Lemon was singing for them all night... he'd start singing about eight and go on until four in the morning... mostly it would be just him sitting there and playing and singing all night.

In the early 1910s, Jefferson began traveling frequently to Dallas, where he met and played with the blues musician Lead Belly.[9] Jefferson was one of the earliest and most prominent figures in the blues movement developing in the Deep Ellum section of Dallas. It is likely that he moved to Deep Ellum on a more permanent basis by 1917, where he met Aaron Thibeaux Walker, also known as T-Bone Walker. Jefferson taught Walker the basics of playing blues guitar in exchange for Walker's occasional services as a guide.[16] By the early 1920s, Jefferson was earning enough money for his musical performances to support a wife and, possibly, a child.[9] However, firm evidence of his marriage and children has not been found.

Beginning of recording career

Prior to Jefferson, few artists had recorded solo voice and blues guitar, the first of which were the vocalist Sara Martin and the guitarist Sylvester Weaver, who recorded "Longing for Daddy Blues", probably on October 24, 1923.[17] The first self-accompanied solo performer of a self-composed blues song was Lee Morse, whose "Mail Man Blues" was recorded on October 7, 1924.[18] Jefferson's music is uninhibited and represented the classic sounds of everyday life, from a honky-tonk to a country picnic, to street corner blues, to work in the burgeoning oil fields (a reflection of his interest in mechanical objects and processes).[19]

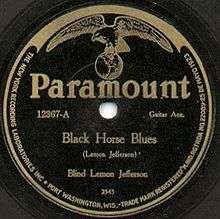

Jefferson did what few had ever done before him – he became a successful solo guitarist and male vocalist in the commercial recording world.[20] Unlike many artists who were "discovered" and recorded in their normal venues, Jefferson was taken to Chicago in December 1925 or January 1926 to record his first tracks. Uncharacteristically, his first two recordings from this session were gospel songs ("I Want to Be Like Jesus in My Heart" and "All I Want Is That Pure Religion"), released under the name Deacon L. J. Bates. A second recording session was held in March 1926.[21] His first releases under his own name, "Booster Blues" and "Dry Southern Blues", were hits. Their popularity led to the release of the other two songs from that session, "Got the Blues" and "Long Lonesome Blues", which became a runaway success, with sales in six figures. He recorded about 100 tracks between 1926 and 1929; 43 records were issued, all but one for Paramount Records. Paramount's studio techniques and quality were poor, and the recordings were released with poor sound quality. In May 1926, Paramount re-recorded Jefferson performing his hits "Got the Blues" and "Long Lonesome Blues" in the superior facilities at Marsh Laboratories, and subsequent releases used those versions. Both versions appear on compilation albums.

Success with Paramount Records

Largely because of the popularity of artists such as Jefferson and his contemporaries Blind Blake and Ma Rainey, Paramount became the leading recording company for the blues in the 1920s.[22] Jefferson's earnings reputedly enabled him to buy a car and employ chauffeurs (this information has been disputed); he was given a Ford car "worth over $700" by Mayo Williams, Paramount's connection with the black community. This was a common compensation for recording rights in that market. Jefferson is known to have done an unusual amount of traveling for the time in the American South, which is reflected in the difficulty of placing his music in a single regional category.

Jefferson's "old-fashioned" sound and confident musicianship made it easy to market him. His skillful guitar playing and impressive vocal range opened the door for a new generation of male solo blues performers, such as Furry Lewis, Charlie Patton, and Barbecue Bob.[20] He stuck to no musical conventions, varying his riffs and rhythm and singing complex and expressive lyrics in a manner exceptional at the time for a "simple country blues singer." According to the North Carolina musician Walter Davis, Jefferson played on the streets in Johnson City, Tennessee, during the early 1920s, at which time Davis and the entertainer Clarence Greene learned the art of blues guitar.[23]

Jefferson was reputedly unhappy with his royalties (although Williams said that Jefferson had a bank account containing as much as $1500). In 1927, when Williams moved to Okeh Records, he took Jefferson with him, and Okeh quickly recorded and released Jefferson's "Matchbox Blues", backed with "Black Snake Moan".[21] It was his only Okeh recording, probably because of contractual obligations with Paramount. Jefferson's two songs released on Okeh have considerably better sound quality than his Paramount records at the time. When he returned to Paramount a few months later, "Matchbox Blues" had already become such a hit that Paramount re-recorded and released two new versions, with the producer Arthur Laibly. In 1927, Jefferson recorded another of his classic songs, the haunting "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" (again using the pseudonym Deacon L. J. Bates), and two other uncharacteristically spiritual songs, "He Arose from the Dead" and "Where Shall I Be". "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" was so successful that it was re-recorded and re-released in 1928.

Death and grave

Jefferson died in Chicago at 10:00 a.m. on December 19, 1929, of what his death certificate said was "probably acute myocarditis".[24] For many years, rumors circulated that a jealous lover had poisoned his coffee, but a more likely explanation is that he died of a heart attack after becoming disoriented during a snowstorm. Some have said that he died of a heart attack after being attacked by a dog in the middle of the night. In his 1983 book Tolbert's Texas, Frank X. Tolbert claims that he was killed while being robbed of a large royalty payment, by a guide escorting him to Chicago Union Station to catch a train home to Texas. Paramount Records paid for the return of his body to Texas by train, accompanied by the pianist William Ezell.[25]

Jefferson was buried at Wortham Negro Cemetery (later Wortham Black Cemetery). His grave was unmarked until 1967, when a Texas historical marker was erected in the general area of his plot; however, the precise location of the grave is still unknown. By 1996, the cemetery and marker were in poor condition, and a new granite headstone was erected in 1997. The inscription reads: "Lord, it's one kind favour I'll ask of you, see that my grave is kept clean." The words come from the lyrics of his own song, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean".[26] In 2007, the cemetery's name was changed to Blind Lemon Memorial Cemetery, and his gravesite is kept clean by a cemetery committee in Wortham.[27][28]

Discography and awards

Jefferson had an intricate and fast style of guitar playing and a particularly high-pitched voice. He was a founder of the Texas blues sound and an important influence on other blues singers and guitarists, including Lead Belly and Lightnin' Hopkins.

He was the author of many songs covered by later musicians, including the classic "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean". Another of his songs, "Matchbox Blues", was recorded more than 30 years later by the Beatles, in a rockabilly version credited to Carl Perkins, who did not credit Jefferson on his 1955 recording. Fellow blues artist B.B. King credited Jefferson as one of his biggest musical influences, next to Lonnie Johnson, Louis Jordan and T-Bone Walker.[29]

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame selected Jefferson's 1927 recording of "Matchbox Blues" as one of the 500 songs that shaped rock and roll.[30] Jefferson was among the inaugural class of blues musicians inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980.

Cover versions

- Canned Heat, "One Kind Favor," on "Living the Blues", released in 1968, (credited: "Arr. & Adpt. by L.T.Tatman III")

- Bukka White, "Jack o' Diamonds", on 1963 Isn't 1962, released in the 1990s

- Bob Dylan, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on Bob Dylan

- Grateful Dead, "One Kind Favor" (a version of "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean"), on Birth of the Dead

- Merl Saunders, Jerry Garcia, John Kahn, Bil Vitt, "One Kind Favor", on Keystone Encores Volume I

- John Hammond, "One Kind Favor", on John Hammond Live

- B.B. King, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on One Kind Favor

- Peter, Paul & Mary, "One Kind Favor", on In Concert

- Kelly Joe Phelps, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on Roll Away the Stone

- The Dream Syndicate, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on Ghost Stories

- Counting Crows, "Mean Jumper Blues". Counting Crows lead singer Adam Duritz accidentally claimed credit for "Mean Jumper Blues" in the liner notes of the deluxe edition reissue of the album August and Everything After. The cover was featured as part of a selection of early demo tracks. Immediately after the error was brought to his attention, Duritz apologized in his personal blog.[31]

- Laibach, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on SPECTRE[32]

- Pat Donohue, "One Kind Favor", live on Garrison Keillor's radio program A Prairie Home Companion and later released on the CD Radio Blues

- Corey Harris, "Jack o' Diamonds", on Fish Ain't Bitin', released in 1997

- Diamanda Galás, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", on The Singer

- Phish, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean", live at Madison Square Garden, New York, August 4, 2017

- Scott H. Biram, "Jack of Diamonds" on Nothin' But Blood released in 2014

- Steve Suffet, "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" on Now the Wheel Has Turned, released in 2005.[33]

In popular culture

- In 2009, the Grammy-nominated R&B act Yarbrough and Peoples were featured in the off-Broadway play Blind Lemon Blues.

- A tribute song, "My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon", was recorded for Paramount Records in 1932 by King Solomon Hill. The record was long considered lost, but a copy was located by John Tefteller in 2002.

- Geoff Muldaur refers to Jefferson in the song "Got to Find Blind Lemon" on the album The Secret Handshake.

- Art Evans portrayed Jefferson in the 1976 film Leadbelly, directed by Gordon Parks.

- Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds recorded the song "Blind Lemon Jefferson" on the album The Firstborn Is Dead.

- The 2010 video game Fallout: New Vegas, in one of its downloadable add-ons Old World Blues, features an AI jukebox named Blind Diode Jefferson.[34] The AI claims to have been a blues musician before his music hard drives were stripped from him. The voicing of the AI can be characterized as a Southern drawl in homage to Jefferson.

- In the 2003 movie Masked and Anonymous, Bobby Cupid (Luke Wilson) gives his friend Jack Fate (Bob Dylan) Jefferson's guitar, which he claims was used in recording "Matchbox Blues".

- Cheech & Chong parodied Jefferson as "Blind Melon Chitlin'" on their self-titled 1971 album Cheech and Chong, on their 1985 album Get Out of My Room, and in a stage routine that can be seen in their 1983 film Still Smokin'.

- Chet Atkins called Jefferson "one of my first finger-picking influences" in the song "Nine Pound Hammer", on the album The Atkins–Travis Traveling Show.

- A practical joke played on Down Beat magazine editor Gene Lees in the late 1950s took on a life of its own and became a long-running hoax when one of his correspondents included a reference to the blues legend "Blind Orange Adams" in an article published in the magazine, an obvious parody of Jefferson's name. References to the nonexistent Adams appeared in subsequent articles in Down Beat over the next few years.[35]

- The American dramatic film Black Snake Moan was named after one of his only songs recorded for Okeh Records.

- Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup took the title of his classic song "That's All Right," which launched the career of Elvis Presley, from a lyric in Jefferson's "Black Snake Moan".[36]

- According to some sources, the "Jefferson" in the name of the rock group Jefferson Airplane references Blind Lemon Jefferson: founding member and blues guitarist Jorma Kaukonen was nicknamed "Blind Lemon Jefferson Airplane" by a friend, and suggested the last part as the name of the band.[37] However, other sources give other origins for the name, involving Blind Lemon Jefferson either more indirectly or not at all.[38]

See also

References

- Bourne, Michael (June 24, 2018). "The Creators of 'Lonesome Blues' Discuss Its Inspiration, Blind Lemon Jefferson, on Blues Break". WBGO. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Campilongo, Jim (March 1, 2019). "Vinyl Treasures: 'The Immortal Blind Lemon Jefferson'". Guitar World. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Davies, David Martin (May 19, 2016). "Texas Matters: The History Of Texas Blues". Texas Public Radio. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Tucker, Simon (September 11, 2013). "Blind Lemon Jefferson: The Rough Guide To Blind Lemon Jefferson – album review". Louder Than War. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Hitchcock, Paul (April 6, 2019). "Blind Lemon Jefferson". WMKY. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- JAZZ AND BLUES LEGENDS The Rough Guide To Blues Legends: Blind Lemon Jefferson World Music Network. Retrieved June 29, 2019

- Obrecht, Jas. "Black Snake Moan / Matchbox Blues" (PDF). Loc.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- Some sources indicate Jefferson was born on October 26, 1894.

- Dicaire, David (1999). Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Legendary Artists of the Early 20th Century. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company. pp. 140–144. ISBN 0-7864-0606-2.

- Charters, Samuel (1977). The Blues Makers. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80438-7.

- "Blind Lemon Jefferson: American Musician". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- 1900 US Census. Census place: Justice precinct 5, Freestone, Texas. Roll T623 1636, p. 3A. Enumeration district 37.

- 1910 US Census. Census place: Justice precinct 6, Navarro, Texas. Roll T624_1580, p. 17B. Enumeration district 98. Image 982.

- World War I Draft Registration records, Dallas County, Texas. Roll 1952850. Draft board 2.

- 1920 US Census. Census place: Kirvin, Freestone, Texas. Roll T625_1805, p. 3A. Enumeration district 24. Image 231.

- Robert Palmer. Deep Blues. Penguin Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- Gibbs, Craig Martin (2012). Black Recording Artists, 1877–1926: An Annotated Discography. McFarland & Company. p. 175.

- Nyback, Dennis W. "Miss Lee Morse: The First Recorded Jazz Singer" (PDF). Washingtonhistory.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Specht, Joe W. (2010). "Oil Well Blues: African-American Oil Patch Songs". Paper presented at joint annual meeting of the East Texas Historical Association and West Texas Historical Association, Fort Worth, February 27, 2010.

- Evans, David (2000). "Music Innovation in the Blues of Blind Lemon Jefferson". Black Music Research Journal. 20 (1): 83–116. JSTOR 779317.

- Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 12. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- Dixon, R. M. W.; Godrich, J. (1970). "Recording the Blues". Reprinted in Oliver, Paul; Russell, Tony; Dixon, Robert M. W.; Godrich, John; Rye, Howard (2001). Yonder Come the Blues. Cambridge. p. 288. ISBN 0-521-78777-7.

- Erbsen, Wayne (1981). "Walter Davis: Fist and Skull Banjo". Bluegrass Unlimited, March 1981. pp. 22–26.

- The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No. 1: The Musicians, the Records & the Music of the 78 Era. Frog Records. 2010. ISBN 0956471706.

- "William Ezell - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean (Blind Lemon Jefferson)". Keeponliving.at. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Jefferson, Blind Lemon". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. May 30, 2010. "In 2007 the name of the cemetery was changed to Blind Lemon Memorial Cemetery."

- "Blind Lemon's Headstone - Picture of Blind Lemon Memorial Cemetery, Wortham". Tripadvisor.co.za. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "B.B. King Clinic 1/5 - Influences". YouTube. March 8, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- "500 Songs That Shaped Rock". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Laibach Spectre". Spectre.laibach.org. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- "♫ Now The Wheel Has Turned - Steve Suffet". Store.cdbaby.com.

- "Blind Diode Jefferson". Falloutwiki.com. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Crow, Bill (1990). Jazz Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–176, ISBN 9780195071337.

- "Big Boy's "That's All Right"". Scotty Moore. 2005-01-16. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Paula Mejia (January 29, 2016). "Jefferson Airplane, Starship Co-Founder Paul Kantner Dies at 74". Newsweek. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

The group was forged shortly afterward with vocalist Grace Slick, bassist Jack Casady and guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, who provided the name for the band, drawn from a blues name he’d been given by a friend (Blind Lemon Jefferson Airplane).

- Clayton Funk and N. G. "Jefferson Airplane". AAEP 1600 (Art and Music since 1945), course materials. Ohio State University. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

Sources

- Govenar, Alan; Brakefield, Jay F. (1998). Deep Ellum and Central Track: Where the Black and White Worlds of Dallas Converged. Denton: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 1-57441-051-2.

Further reading

- Evans, David (2000). "Musical Innovation in the Blues of Blind Lemon Jefferson". Black Music Research Journal. Vol. 20, no. 1, Blind Lemon Jefferson (Spring 2000). pp. 83–116.

- Monge, Luigi (2000). "The Language of Blind Lemon Jefferson: The Covert Theme of Blindness". Black Music Research Journal. Vol. 20, no. 1, Blind Lemon Jefferson (Spring 2000). pp. 35–81.

- Monge, Luigi; Evans, David (2003). "New Songs of Blind Lemon Jefferson". Journal of Texas Music History. Vol. 3, no. 2 (Fall 2003).

- Pisigin, Valeriy (2013). The Coming of the Blues (Пришествие блюза). Vol. 4. Country Blues. Blind Lemon Jefferson. — M.: 2013. — C.320. ISBN 978-5-9902482-7-4.

- Uzzel, Robert L. (2002). Blind Lemon Jefferson: His Life, His Death, and His Legacy. Austin, Texas: Eakin Press. ISBN 9781571686565.