Berardius

Four-toothed whales or giant beaked whales are beaked whales in the genus Berardius. They include Arnoux's beaked whale (Berardius arnuxii, minami-tsuchi) in cold Southern Hemisphere waters, and Baird's beaked whale (Berardius bairdii, "tsuchi-kujira") in the cold temperate waters of the North Pacific. A third species, Berardius minimus, (Latin transliteration="least four-toothed whale", commonly called "kuro-tsuchi" or Sato's beaked whale) was distinguished from B. bairdii in the 2010s.[1]

| Berardius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo of Arnoux's beaked whale | |

| |

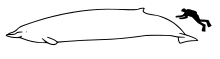

| Illustration of Baird's beaked whale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Ziphiidae |

| Subfamily: | Berardiinae |

| Genus: | Berardius Duvernoy, 1851 |

| Species | |

| |

| |

| Arnoux's beaked whale range | |

| |

| Baird's beaked whale range | |

Arnoux's and Baird's beaked whales are so similar that researchers have debated whether or not they are simply two populations of the same species. However, genetic evidence and their wide geographical separation has led them to be classified as separate.[2] Lifespan estimates, based on earwax plug samples, indicate these whales can live up to 85 years.[3] At ~4m at birth, growing to ~10m, these are the largest whales belonging to the family Ziphiidae. The kurotsuchi is much smaller, with adult males having a length of ~7m.

This article currently largely treats four-toothed whales as monospecific, due to a lack of species-specific information.

Species

Berardius was once classified as containing only two species: Arnoux's beaked whale (Berardius arnuxii) in the Southern Hemisphere waters, and Baird's beaked whale (Berardius bairdii) in the North Pacific.[4] Arnoux's beaked whale was described by Georges Louis Duvernoy in 1851. The genus name honors admiral Auguste Bérard (1796-1852), who was captain of the French corvette Le Rhin (1842-1846), which brought back the type specimen to France where Duvernoy analyzed it; the species name honors Maurice Arnoux, the ship's surgeon who found the skull of the type specimen on a beach near Akaroa, New Zealand.[5] Baird's beaked whale was first described by Leonhard Hess Stejneger in 1883 from a four-toothed skull he had found on Bering Island the previous year. The species is named for Spencer Fullerton Baird, a past Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.[6]

Researchers have debated over whether the northern and southern populations represent distinct species or whether they are simply geographic variants.[7] Several morphological characters have been suggested to distinguish them, but the validity of each has been disputed;[8][9][10] currently, it seems that there are no significant skeletal or external differences between the two forms, except for the smaller size of the southern specimens known to date.[11][12] The morphological similarity gave rise to the hypothesis that the populations were sympatric as recently as the last Pleistocene Ice Age, approximately 15,000 years ago,[4][13] but subsequent genetic analyses suggest otherwise.[2] Phylogenetic analyses of the mitochondrial DNA control region (D-loop) revealed that Baird's and Arnoux's beaked whales were reciprocally monophyletic — lineages from each of the species grouped together to the exclusion of lineages from the other species. Diagnostic DNA substitutions were also found. These results are consistent with the current classification of Baird's and Arnoux's beaked whales as distinct species. Further, the degree of differentiation between the northern and southern forms of Berardius suggest that the species may already have been separated for several million years.[2]

Genetic evidence suggests that the Baird's and Arnoux's whales separated from one another after their common ancestor separated from the kurotsuchi;[14] however, this is not certain.[1] They are deep divers that can spend long periods of time submerged below the surface of the water and thus are difficult to study.[15][16] They are considered part of the smaller mysticetes in regards to overall size.[17]

Possible species

Sightings during whale watching tours and studies of stranded individuals suggest the possibility of another form of Berardius in the Sea of Okhotsk inclusive of the coast of northern Hokkaido especially around Shiretoko Peninsula and off Abashiri,[18] or to Sea of Japan off Korean Peninsula and north pacific and Bering Sea off Alaska.[19] These whales are generally much smaller than known species (6–7 m or 20–23 ft), darker in color, and inhabit shallow waters closer to coastal areas, enough to be trapped within fixed nets for salmon.[20] Local whalers had called them "kurotsuchi" (= black Berardius)[21][1] or "karasu" (= ravens); it is not known whether these terms are synonyms or identify two separate species.[1] Genetic studies indicate that kurotsuchi are Berardius minimus, recognized as a distinct species in the 2010s.[1][14]

"Bottlenose whales in the Sea of Okhotsk" had been reported since the time of the Soviet Union's whaling,[22] and an unknown type of beaked whale resembling Baird's beaked whales having four tusks on upper and lower jaws has also been recorded by traditional whalers in Japan.[23] It is unknown whether these records correspond with this new form.

An unknown type of large beaked whale of similar size to fully grown Berardius bairdii have been reported to live in the Sea of Okhotsk, somewhat resembling Longman's beaked whale. The "Moore's Beach monster", an initially unidentified carcass found in 1925 on Moore's Beach on Monterey Bay, was identified by the California Academy of Sciences as a Baird's beaked whale.[24][25] There have been claims that records of strandings of these whales exist along the areas within and adjacent to Tatar Strait in the 2010s.[26]

Physical description

The two established species have very similar features and would be indistinguishable at sea if they did not exist in disjoint locations.[27] Both whales reach similar sizes, have bulbous melons, and long prominent beaks. Their lower jaw is longer than the upper, and the front teeth are visible even when the mouth is fully closed.[27][28] The Baird’s and Arnoux beaked whales in the family Ziphiidae are the only whales in this family that both sexes have erupted teeth.[17] The teeth in the Ziphiidae are used by the males for fighting and competition of females. The teeth are called ‘battle teeth. Ziphidae has the most prevalent and pronounced markings caused by teeth scaring among the cetaceans. These modified teeth are presumed to be used for battle.[17]

This can result in having their front facing teeth being covered in barnacles after many years.[28] Baird's and Arnoux's also have similarly shaped small flippers with rounded tips, and small dorsal fins that sit far back on their body.[28] Adult males and females of both species pick up numerous white linear scars all over the body as they age, and may be a rough indicator of age.[17] These traits are similar in both sexes as there is little sexual dimorphism in either species.[27][28]

Although fairly similar, there exist some differences between both species. Baird's beaked whales are around 4.6 meters when born, and can reach lengths of 11.1 meters as adults, making them the largest members of the beaked whale family. Female Baird’s and Arnoux beaked whales are slightly larger than the males.[17]

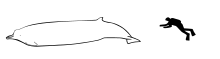

Baird's have fairly narrow body shapes despite their large size, and have dorsal fins that are rounded at the tips. Their coloration is fairly uniform and can range from brown to grey.[28] Arnoux's beaked whales are around four meters as calves and can reach lengths up to 9.75 meters as adults.[27] Their bodies are not as narrow as the Baird's, and resemble a spindle. Unlike the Baird's beaked whale, Arnoux's have slightly hooked dorsal fins.[27] Arnoux's beaked whales have a dark coloration that ranges from brown to orange due to a buildup of algae on its body.[27]

A third species, B. minimus, (known by the Japanese common name "kurotsuchi", which means "black Berardius") was formally named in 2019,[1][29] after being distinguished in 2016, based on differences in haplotypes from mtDNA.[30] It generally has a short beak (~4% body length). While other four-toothed whales are generally grey with scars, kurotsuchis usually have few linear scars, so that the dark, smooth skin contrasts highly with round, white scars of about 5 cm diameter (from cookiecutter shark bites).[31] The tip of the rostrum is also white. The kurotsuchi is shorter than other four-toothed whales, around 6-7m long at maturity, hence the species name, B. minimis (="smallest"). No females of this species have yet been described in the research literature.[1]

Population and distribution

The total population is not known for two of the three species. Estimates for Baird's are of the order of 30,000 individuals. Nothing is known at all about the population size of the third species of Berardius, first scientifically described in the 2010s.[31][1] Baird's and Arnoux's beaked whales have an allopatric (non-overlapping) antitropical distribution;[32] kurotsuchis are known to live in the North Pacific.[1]

Arnoux's

Arnoux's beaked whales inhabit great tracts of the Southern Ocean. Large groups of animals, pods of up to 47 individuals, have been observed off Kemp Land, Antarctica.[32] Beachings in New Zealand and Argentina indicate the whale may be relatively common in the Southern Ocean between those countries and Antarctica; sporadic sightings have been recorded in polar waters, such as in McMurdo Sound.[33] It has also been spotted close to South Georgia and South Africa, indicating a likely circumpolar distribution. The northernmost stranding was at 34 degrees south, indicating the whales inhabit cool and temperate, as well as polar, waters. There is no stock report for the Arnoux’s beaked whale to date by NOAA.

Baird's

Baird's beaked whale is found in the North Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan and the southern part of the Sea of Okhotsk.[34] They appear to prefer seas over steep cliffs at the edge of the continental shelf, but are known to migrate to oceanic islands and to near shore waters where deep cliffs locate next to landmasses such as at Rishiri Island and in Tsugaru Strait, Shiretoko Peninsula, Tokyo Bay, and Toyama Bay.[28]

The continental shelf was reported in the Alaska stock report as the whales migrate to the shelf in the summer months during when the water temperature are at the highest.[35] According to the California/Oregon/Washington NOAA stock assessment report the Baird’s beaked whales can be found in the deep waters along the continental slopes of the North Pacific Ocean.[4][36][37] They are often seen along the slope between late spring to early fall.

Specimens have been recorded as far north as the Bering Sea and as far south as the Baja California Peninsula.[38][36] They are also found on the east side and the southern islands (Izu and Bonin Islands) of Japan on the west although it is unclear whether records at these islands are of Berardius bairdii. Southern limits of historical occurrences in east Asian were unclear, while there had been either a stranding or a catch in East China Sea at Zhoushan Islands in the 1950s,[39][40] and was a disentanglement at Kamae, Ōita.[41] Whales off the east coast of North America seems to approach coasts less frequently than in the western North Pacific, but they may travel further south than in Japan. Historical distributions of southward migrations or vagrants in Asian waters are unknown as the whales wintering from Bōsō Peninsula and in Tokyo Bay to Sagami Bay and around Izu Ōshima have been severely depleted or nearly wiped out by modern whaling (recently whalers shifted their major hunting grounds from Bōsō Peninsula to further north due to the very small numbers of whales still migrating to the former habitats). Within the Sea of Japan, the first scientific approaches to the species were made in Peter the Great Gulf, and the whales can widely distribute more on Japanese archipelago from west of Rebun Island to west of Oki Islands on unknown regularities, and major whaling grounds were in Toyama Bay and Oshima Peninsula.[42][40]

The historic and current status of the northern species in northwestern coastal Pacific outside the Japanese EEZ are vague, especially within North and South Korea and China. Some groups still survive in the Japanese archipelago but are under serious threat by commercial whaling activities. The species is not thought to occur in Chinese waters (or at least is not resident), and the origin of a skeletal specimen at the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, although claimed to be national, is unreliable.[43] However, archaeological and capture records by Japanese whalers suggest that there may have been historical migrant groups of Baird's beaked whales that once regularly reached the Yellow and Bohai Seas, especially around the island of Lingshan off Jiaozhou Bay and off Dalian, at least until the mid-16th century, until being wiped out by Japanese whalers.[44] This may have included regions at least as far south as the Zhoushan archipelago.[39] See also Wildlife of China for natural histories of large cetaceans in this region. 12 individuals were caught as by-catch along the east coasts of the Korean Peninsula between 1996 and 2012.[45] Canada; Japan; Korea, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; Mexico; Russian; United States, (Taylor et al. 2008). Endemic to the North Pacific Ocean and the adjacent seas. There are two different stocks of Baird beaked whales that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) keeps track of for management of the species, the Alaska stock and the California-Oregon-Washington stock. (NOAA website). According to the Alaska 2017 stock report, the range of the Baird's beaked whale is north of the Cape Navarn (62o N) and Central Sea of Okhotsk (57o N) that spans to St. Matthew Island, the Pribilof Islands, and the northern Gulf of Alaska. (Alaska Stock assessment report and Balcomb 1989).

The seasonal distribution can be observed when the Baird’s beaked whales spend the summer months in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea between April–May to October. (Tomilin 1957, Kasuya 2002, Alaska Stock assessment report 2017). The wintering habitats is assumed to be located in the northern Gulf of Alaska which was determined by using acoustic detection, (Baumann-Pickering et al. 2012b. and Alaska Stock assessment report 2017.)

Behavior

Little is known about the behavior of Arnoux's beaked whale, but it is expected to be similar to that of Baird's. Distinctions between the two species are so slight that they are speculated to be the same, although genetic makeup and geographic distribution show otherwise.[2] Baird's beaked whales generally move in pods of 5 to 20 individuals, with groups of 50 observed in rarer circumstances.[46] Congregating groups of Baird's Beaked whales are led by a single large male. Scarring among males indicate competition for this leadership position that must entail more breeding opportunities and gives evidence that the species' behaviors portray sexual selection.[47] Potentially one of the deepest diving cetaceans, they can dive for an hour at a time, predating on deep-water and bottom-dwelling fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. When not diving, they drift along the surface.[15] The deep diving whales can dive to depths of 800–1200 meters, and when feeding, they generally prefer deep waters near the continental shelf or around seamounts, where high biological activity is present in shallower waters.[48] The deepest recorded dive is 1777 meters.[49][50]

Diel variation in behavior suggests that beaked whales spend less time at the surface during the day than they do at night, so as to avoid surface predators like sharks and killer whales.[51] Considering the extent of whaling on the Baird's species, the pod's uninfluenced structure is not well known. To date, two-thirds of the whales caught have been male, despite the fact that females are somewhat larger than males and would be thought to be the preferred targets for whalers.[17] Despite their still being hunted by whalers and researchers near Japan, there isn't sufficient enough data to predict its IUCN status and whether or not it is endangered or vulnerable.[52] They are not listed as “threatened” or “endangered” under the endangered species act nor depleted under the MMPA.[37] They are not being hunted for research due to Japan pulling out of the whaling commission in 2018/2019.

Observations of Arnoux's beaked whales in Doubtful Sound, New Zealand in the same seasons in 2009[53] and in 2010[54] indicate that this species may possess a form of bond to locations similar to those of other species such as right whales. Another 4 or 5 sightings have been recorded in the Doubtful Sound between 2007 and in 2011.[55][56] Underwater recordings, made in the austral summer in the Antarctic of a large (47 animal) group of Arnoux's beaked whales showed that these whales are highly vociferous animals at this time. Animals produced clicks, click trains, and frequency modulated pulses and whistles which gives their vocalizations a characteristic warbling aural impression.[32] Animals swam in coordinated positions along the ice edge, groups of whales splitting and reassembling.[32]

Reproduction

Mating in Baird's beaked whales happens in the months of October and November and calving occurs in March and April after a 17-month gestational period.[47] Scarring among males indicate competition for leadership position that must entail more breeding opportunities and gives evidence that the species' behaviors portray sexual selection.[47][17] The sex ratio seems to be skewed in favor of males from observational data; with some observations indicating as high is 3:1.[57] Males are recorded to live longer. Males live 39 years longer than females with the adult sex ratio strongly biases toward males and the female’s exhibit high annual ovulation.[17] It is possible that these results are seasonal abundances of different sexes in the region studied. They exhibit a slight reverse sexual dimorphism with females tending to be larger than males in size. The females have no post-reproductive stage.[58][17] Cetaceans in general have a interbirth interval which is the time between births of new calves. The mysticetes tend to have two or three years or relative to body size intervals whereas the odontocete interbirth intervals are more varied.[17] Baird beaked whales have interbirth intervals similar to mysticeti to their size than they do with other odontocetes.[17] In July 2006, in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico, there was summer stranding event of 10 males of mixed age composition that was highly suggestive of male alloparental care.[59][38] Females are slightly larger than the males and exhibit high annual ovulation and pregnancy rates. Males live about 30 years longer than the females with this sex ratio biased toward males it is speculated that the males provide alloparetnel care to offspring which in turn allows the females to have a shorten birth interval frequency.[17]

Feeding

Baird's beaked whale has a diet that consists primarily of deep sea fish and cephalopods found at its preferred dive depths (1000–1777m).[49][50] On rare occasions, it has been known to eat octopus, lobster, crab, rockfish, herring, starfish, pyrosomes and sea cucumbers.[34] Baird’s beaked whales in the southern Sea of Okhotsk diet consists of deep-water gadiform fishes and cephalopods.[34] The species has a mean dive time of about 1 hour, which suggests a long search and handling time.[35][34] Its generalist feeding strategy may be reflective of limited prey availability at such depths or regions, as mammals become more general feeding strategists as prey diversity decreases. It may also explain the species' migrational patterns around the North Pacific.[34] In summer months, Baird's beaked whale can be found off the Pacific coast of Japan where demersal fish are abundant.[34] Stomach content analysis's found that Baird's beaked whale feeds in benthic zones both day and night. This behavior differs from its other Odontocete relatives (namely the common dolphin and Dall's porpoise) who feed in mesopelagic regions during the day when the light can penetrate the water column.[60] This suggests that Baird's beaked whale does not rely as much on its sense of sight and has evolved to navigate and hunt competently with echolocation.[61] There is little information on the foraging behavior of Baird’s beaked whales and their ecological role in the marine ecosystem.[34]

Conservation

_(20525816381).jpg)

Arnoux's beaked whale has rarely been exploited, and although no abundance estimates are available, the population is not believed to be endangered. Arnoux's beaked whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU).[62]

The conservation status of Baird's beaked whales is not known globally;[63] the Mammalogical Society of Japan lists them as rare in Japanese coastal waters. The Baird's beaked whale is listed on Appendix II [64] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II [64] as it has an unfavorable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. It is considered Data Deficient by the IUCN.[63] They are not listed as “threatened” or “endangered” under the endangered species act nor depleted under the MMPA.[37] There is preliminary evidence of the Baird's beaked whale being sensitive to anthropogenic aquatic noise pollution, as other odontocete species are.[65][66] Anthropogenic sound sources such as military sonar and seismic testing. The testing of military sonar has been recorded to effect the diving behavior of beaked whales. This implication on the whales effects their ability to decompress upon surfacing and results in the whales suffering the bends, increase nitrogen gas bubbles in the blood.[15][37]

In the 20th century, Baird's beaked whales were hunted primarily by Japan and to a lesser extent by the USSR, Canada and the United States. The USSR reported killing 176 before hunting ended in 1974. Canadian and American whalers killed 60 before halting in 1966. Japan killed around 4000 individuals before the 1986 moratorium on whaling (about 300 were killed in the most prolific year, 1952). Baird's beaked whales are not protected under the International Whaling Commission's moratorium on commercial whaling, as Japan argues they are a 'small cetacean' species, despite being larger than minke whales, which are protected. Each year, 62 Baird's beaked whales are hunted commercially in Japan, with the meat sold for human consumption. A landing and processing of a Baird's beaked whale was filmed[67] by the Environmental Investigation Agency on 7 August 2009. Meat and blubber food products of the whales have been found to contain high levels of mercury and other pollutants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Population status

Estimates of the abundance of populations are unavailable.[37] They are not listed as “threatened” or “endangered” under the endangered species act nor depleted under the MMPA.[37]

Threats

Hunted by Japan. As of 2019, Japan pulled out of the International whaling commission to continue harvesting whales.[68] The California large mesh drift gillnet fishery has known to interact with the CA-OR-WA population. There are habitat concerns for the Alaska stock, in areas with oil and gas activities or shipping and military activities are high.[37] For the Baird’s beaked whale.[69][70][71] Anthropogenic sound sources such as military sonar and seismic testing. The testing of military sonar has been recorded to effect the diving behavior of beaked whales. This implication on the whales effects their ability to decompress upon surfacing and results in the whales suffering the bends, increase nitrogen gas bubbles in the blood.[15][37]

Common names

- B. arnuxii is known as Arnoux's beaked whale, southern four-toothed whale, southern beaked whale, New Zealand beaked whale, southern giant bottlenose whale, and southern porpoise whale. In Japanese it is known as minami-tsuchi (ミナミツチ), literally "Southern hammer (i.e. Berardius)".

- B. bairdii is known as Baird's beaked whale, northern giant bottlenose whale, North Pacific bottlenose whale, giant four-toothed whale, northern four-toothed whale, and North Pacific four-toothed whale. In Japanese, it is called tsuchi-kujira (ツチクジラ), where tsuchi means "hammer", in reference to the way the head vaguely resembles a traditional Japanese hammer or mallet, and kujira means "whale"[72]

- The newly-described species, B. minimus, is traditionally known to Japanese whalers as kuro-tsuchi (黒ツチ),[1] where kuro means "black" and tsuchi means "hammer".[72] The Society for Marine Mammalogy lists Sato's beaked whale as an additional common name for B. minimus.[73]

Specimens

- MNZ MM002654 B. arnuxii Arnoux's beaked whale, collected Riverton, near Invercargill, New Zealand, 27 January 2006

See also

References

- Yamada, Tadasu K.; Kitamura, Shino; Abe, Syuiti; Tajima, Yuko; Matsuda, Ayaka; Mead, James G.; Matsuishi, Takashi F. (30 August 2019). "Description of a new species of beaked whale (Berardius) found in the North Pacific". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 12723. Bibcode:2019NatSR...912723Y. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46703-w. PMC 6717206. PMID 31471538.

- Dalebout (2002). Species identity, genetic diversity and molecular systematic relationships among the Ziphiidae (beaked whales). PHD Thesis, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand (Thesis).

- "Berardius bairdii". The Moirai - Aging Research. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Balcomb (1989). "Baird's beaked whale, Berardius bairdii Stejneger, 1883: Arnoux's beaked whale, Berardius arnuxii Duvernoy, 1851". Handbook of Marine Mammals. 4. London: Academic Press. pp. 261–288.

- Beolens, Bo, Michael Watkins, and Michael Grayson. 2009. The eponym dictionary of mammals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 38, 54.

- Sharks and Whales (Carwardine et al. 2002), p. 356.

- McCann (1975). "A study of the genus Berardius". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 27: 111–137. ISSN 0083-9086.

- Kasuya (1973). "Systematic consideration of recent toothed whales based on the morphology of the tympano-periotic bone". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 21: 1–103.

- McLachlan (1966). "A record of Berardius arnouxi from the South-East Coast of South Africa". Annals of the Cape Provincial Museum (Natural History). 5: 91–100.

- Slipp (1953). "The beaked whale Berardius on the Washington Coast". Journal of Mammalogy. 34 (1): 105–113. doi:10.2307/1375949. JSTOR 1375949.

- Rice (1998). Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publication Number 4. The Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- Ross (1984). "The smaller cetaceans of the south east coast of southern Africa". Annals of the Cape Provincial Museum (Natural History). 15: 173–410.

- Davies (1963). "The antitropical factor in cetacean speciation". Evolution. 17 (1): 107–116. doi:10.2307/2406339. JSTOR 2406339.

- Kennedy, Merrit (27 July 2016). "Mysterious and Known as the 'Raven': Scientists Identify New Whale Species". NPR. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Cox, Tara. M.; et al. (2006). "Understanding the impacts of anthropogenic Sound on beaked whales". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 7: 177–187.

- Baumann-Pickering, S.; et al. (2012b). "Passive Acoustic Monitoring for Marine Mammals in the Gulf of Alaska Temporary Maritime Activities Area 2011-2012". Marine Physical Laboratory, Scripps Institute of Oceanography. 538.

- Mann, J.; et al. Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales. Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 231, 261.

-

- Kitano S., 2013. DNAで未知の鯨種に挑む-日本近海のツチクジラについて-. Cetoken Newsletter No.32. Retrieved on January 26, 2014

- Shiretoko Nature Cruise. 2013. 羅臼の海大集合! 知床ネイチャークルーズ ニュース Archived 19 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 January 2014

- Uni Y., Koyama K., Nakagun S., Maeda M., 2014. Sighting Records of Cetaceans and Sea Birds in the Southern Okhotsk Sea, off Abashiri, Hokkaido Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Bulletin of the Shiretoko Museum 36: pp.29–40. Retrieved on 30 May 2014

- Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, 2016, New species of beaked whale_or is it ? Archived 14 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Uni Y., Photos from Abashiri Nature Cruise Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- the term "tsuchi" is used for the whole genus

- Uni Y.,2006 Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises off Shiretoko Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Bulletin of the Shiretoko Museum 27: pp.37-46. Retrieved on 26 January 2014

- T. Kasuya, 2011. イルカ―小型鯨類の保全生物学. University of Tokyo Press. Retrieved on 26 January 2014

- Long, Douglas (18 November 2014). "Lies, Damned Lies, and Cryptozoology". Deep Sea News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- McLellan Davidson, M.E. (November 1929). "Baird's Beaked Whale at Santa Cruz, California". General Notes. Journal of Mammalogy. 4 (10): 356–358. doi:10.2307/1374126. JSTOR 1374126.

- Smolin S. (2010). "Зубатый кит выброшен на брекватер Невельского порта". Сахалин и Курилы. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- "Arnoux's beaked whale". Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- "Baird's beaked whale". WDC, Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "tsuchi" is also used to describe the entire genus, including Arnoux's, not just Baird's as suggested by the research paper.

- Morin, P. A.; Scott Baker, C.; Brewer, R. S.; Burdin, A. M.; Dalebout, M. L.; Dines, J. P.; Fedutin, I.; Filatova, O.; Hoyt, E.; Jung, J.-L.; Lauf, M.; Potter, C. W.; Richard, G.; Ridgway, M.; Robertson, K. M.; Wade, P. R. (2016). "Genetic structure of the beaked whale genus Berardius in the North Pacific, with genetic evidence for a new species". Marine Mammal Science. 33: 96–111. doi:10.1111/mms.12345. S2CID 88899974.

- Morin, Phillip A. (2017). "Genetic structure of the beaked whale genus Berardius in the North Pacific, with genetic evidence for a new species". Marine Mammal Science. 33: 96–111. doi:10.1111/mms.12345. S2CID 88899974.

- Rogers, Tracey L.; Brown, Sarah M. (1970). "Acoustic observations of Arnoux's beaked whale (Berardius arnuxii) off Kemp Land, Antarctica". Marine Mammal Science. 15: 192–198. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00789.x.

- "Mystery Whales Put on Show at Scott Base | EveningReport.nz". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Walker, William A.; Mead, James G.; Brownell, Robert L. (October 2002). "Diets of Baird's Beaked Whales, Berardius bairdii, in the Southern Sea Of Okhotsk and O the Paci c Coast Of Honshu, Japan". Marine Mammal Science. 18 (4): 902–919. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01081.x.

- Kasuya, T (1986). "DISTRIBUTION AND BEHAVIOR OF BAIRD'S BEAKED WHALES OFF THE PACIFIC COAST OF JAPAN". Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 37.

- MacLeod, Colin D., et al. "Known and inferred distributions of beaked whale species (Cetacea: Ziphiidae)." Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 7.3 (2006): 271-286.

- Carretta, J.V.; et al. (2019). "U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments-2018". U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-617: 157–172.

- Urban, Jorge & Cárdenas Hinojosa, Gustavo & Gomez Gallardo Unzueta, Alejandro & González-Peral, U & Del Toro-Orozco, Wezddy & Brownell Jr, RL. (2007). Mass stranding of Baird's beaked whales at San Jose Island, Gulf of California, Mexico. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 6. 83-88. 10.5597/lajam00111.

- Huogen W.; Yu W. (1998). "A Baird's Beaked Whale From the East China Sea". Fisheries Science, 1998-05: CNKI – The China National Knowledge Infrastructure. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Kasuya T.(jp). 2017. Small Cetaceans of Japan: Exploitation and Biology Archived 25 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. "13.3.2 Regional distribution and population structure". CRC Press. Retrieved on September 25, 2017

- Hirano K.. 第四章 哺乳動物 Archived 26 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine (pdf). Retrieved on February 27, 2017

- Nishimura, Saburo (1970). "Recent Records of Baird's Beaked Whales in Japan Sea" (PDF). Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory. 18 (1): 61–68. doi:10.5134/175618. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Kaiya, Zhou; Leatherwood, Stephen; Jefferson, Thomas A. (1995). "Records of Small Cetaceans in Chinese Waters: A Review" (PDF). Asian Marine Biology. 12: 119–39. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Kamio A. (1942). "About the accidents in history of Southeastern Santô peninsula". Geographical Review of Japan. 18 (7): 605–609. doi:10.4157/grj.18.605.

- Chang K.; Zhang C.; Park C.; Kang D.; Ju S.; Lee S.; Wimbush M., eds. (2015). Oceanography of the East Sea (Japan Sea). Springer International Publishing. p. 380. ISBN 9783319227207. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- "Baird's beaked whale". WDC, Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- "Berardius bairdii (Baird's beaked whale)". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "Baird's beaked whale". WDC, Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Gregory S. Schorr; Erin A. Falcone; David J. Moretti; Russel D. Andrews (2014). "First long-term behavioral records from Cuvier's beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris) reveal record-breaking dives". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e92633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092633. PMC 3966784. PMID 24670984.

- Lee, Jane J. (26 March 2014). "Elusive Whales Set New Record for Depth and Length of Dives Among Mammals". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- Baird, Robin (21 July 2008). "Diel variation in beaked whale diving behavior". Marine Mammal Science. 24 (3): 630–642. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.578.8208. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00211.x. hdl:10945/697.

- Taylor. "Berardius bairdii (Baird's Beaked Whale, Four-toothed Whale, Giant Bottle-nosed Whale, Northern Four-toothed Whale, North Pacific Bottlenose Whale, Pacific Giant Bottlenosed Whale)". www.iucnredlist.org. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Matthews Z., Whales at Doubtful Sound, Fiordland Kindergarten-Blog of Fiordland Nature Discovery, 28 April 2009, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)., Retrieved 4 May 2014

- Department of Conservation, April 2011, Fiordland Coastal Newsletter - Conservation for prosperity – Tiakina te taiao, kia puawai, http://www.fiordlandhelicopters.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Fiordland-Coastal-Newsletter-April-2011.pdf Archived 13 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Retrieved 4 May 2014

- Rockwell D.H., 2009, When in Rome, Do as the Whales Do! Archived 4 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Hudgins J., Bachara W., 2014. Multiple Opportunistic Observations of Arnoux’s beaked whales in Doubtful Sound (Patea). SC/65b/SM19. Retrieved 14 May 2014

- Omura, Hideo, Kazuo Fujino, and Seiji Kimura. "Beaked whale Berardius bairdi of Japan, with notes on Ziphius cavirostris." Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 10 (1955): 89-132.

- "Baird's Beaked Whale (Berardius bairdii)". Marine Species Identification Portal. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Riedman, Marianne L. (1982). "The Evolution of Alloparental Care and Adoption in Mammals and Birds". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 57 (4): 405–435. doi:10.1086/412936. ISSN 0033-5770.

- Ohizumi, H. , Isoda, T. , Kishiro, T. and Kato, H. (2003), Feeding habits of Baird's beaked whale Berardius bairdii, in the western North Pacific and Sea of Okhotsk off Japan. Fisheries Science, 69: 11-20. doi:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00582.x

- Shingo Minamikawa, Toshihide Iwasaki and Toshiya Kishiro, Diving behaviour of a Baird's beaked whale, Berardius bairdii, in the slope water region of the western North Pacific: first dive records using a data logger, Fisheries Oceanography, 16, 6, (573-577), (2007)

- "CMS Pacific Cetaceans MOU for Cetaceans and their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region". Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Taylor, B.L.; Baird, R.; Barlow, J.; Dawson, S.M.; Ford, J.; Mead, J.G.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. (2008). "Berardius bairdii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T2763A9478643. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T2763A9478643.en.

- "Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

- Stimpert, A. K.; DeRuiter, S. L.; Southall, B. L.; Moretti, D. J.; Falcone, E. A.; Goldbogen, J. A.; Friedlaender, A.; Schorr, G. S.; Calambokidis, J. (13 November 2014). "Acoustic and foraging behavior of a Baird's beaked whale, Berardius bairdii, exposed to simulated sonar". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 7031. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E7031S. doi:10.1038/srep07031. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4229675. PMID 25391309.

- Quick, Nicola; Scott-Hayward, Lindesay; Sadykova, Dina; Nowacek, Doug; Read, Andrew (May 2017). "Effects of a scientific echo sounder on the behavior of short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus)" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 74 (5): 716–726. doi:10.1139/cjfas-2016-0293. hdl:10023/9555. ISSN 0706-652X.

- "Video: Aftermath of a Japanese whale hunt". Archived from the original on 21 September 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Fobar, Rachel (26 December 2018). "Japan will resume commercial whaling and leave the IWC". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019.

- 11) Aguilar deSoto, N (2006). "Does intense ship noise disrupt foraging in deep diving Cuvier's beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris)?". Marine Mammal Science. 22 (3): 690–699. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00044.x. S2CID 13705374.

- Tyack, P.L.; et al. (2011). "Beaked Whales Respond to Simulated and Actual Navy Sonar". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17009. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617009T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017009. PMC 3056662. PMID 21423729.

- McCarthy, E (2011). "Changes in spatial and temporal distribution and vocal behavior of Blainville's beaked whales (Mesoplodon densirostris) during multiship exercises with mid-frequency sonar". Marine Mammal Science. 27 (3): 206–226. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00457.x.

- 1995, 大辞泉 (Daijisen) (in Japanese), Tōkyō: Shogakukan, ISBN 4-09-501211-0

- "List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies|May 2020". Society for Marine Mammalogy. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Giant Beaked Whales" in the Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals pages 519-522 Teikyo Kasuya, 1998. ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World Reeves et al., 2002. ISBN 0-375-41141-0.

- Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises Carwardine, 1995. ISBN 0-7513-2781-6

- An image of a Baird's Beaked Whale at monteraybaywhalewatch.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Berardius. |

- The Environmental Investigation Agency

- Whale & Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS)

- Baird's Beaked Whale - ARKive bio

- Arnoux's Beaked Whale - ARKive bio

- Arnoux's beaked whale - The Beaked Whale Resource

- Baird's beaked whale - The Beaked Whale Resource

- Rare whale gathering sighted - BBC News

- Species Convention on Migratory species page on Baird's Beaked Whale

- Voices in the Sea - Sounds of the Baird's (Giant) beaked Whale