Benznidazole

Benznidazole is an antiparasitic medication used in the treatment of Chagas disease.[2] While it is highly effective in early disease this decreases in those who have long-term infection.[3] It is the first-line treatment given its moderate side effects compared to nifurtimox.[1] It is taken by mouth.[2]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Rochagan, Radanil[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.153.448 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

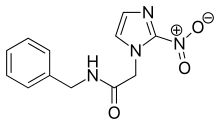

| Formula | C12H12N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 260.253 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 188.5 to 190 °C (371.3 to 374.0 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects are fairly common.[4] They include rash, numbness, fever, muscle pain, loss of appetite, and trouble sleeping.[4][5] Rare side effects include bone marrow suppression which can lead to low blood cell levels.[1][5] It is not recommended during pregnancy or in people with severe liver or kidney disease.[4][3] Benznidazole is in the nitroimidazole family of medication and works by the production of free radicals.[5][6]

Benznidazole came into medical use in 1971.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] It is not commercially available in the United States, but can be obtained from the Centers of Disease Control.[2] As of 2012 Laboratório Farmacêutico do Estado de Pernambuco, a government run pharmaceutical company in Brazil was the only producer.[8]

Medical uses

Benznidazole has a significant activity during the acute phase of Chagas disease, with a success rate of up to 80%. Its curative capabilities during the chronic phase are, however, limited. Some studies have found parasitologic cure (a complete elimination of T. cruzi from the body) in children during the early stage of the chronic phase, but overall failure rate in chronically infected individuals is typically above 80%.[6]

Some studies indicate treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase, even if incapable of producing parasitologic cure because it reduces electrocardiographic changes and delays worsening of the clinical condition of the patient.[6]

Benznidazole has proven to be effective in the treatment of reactivated T. cruzi infections caused by immunosuppression, such as in people with AIDS or in those under immunosuppressive therapy related to organ transplants.[6]

Children

Benznidazole can be used in children, with the same 5–7 mg/kg per day weight-based dosing regimen that is used to treat adult infections.[9] A formulation for children up to two years of age is available.[10] It was added to the WHO Essential Medicines List for Children in 2013.[11] Children are found to be at a lower risk of adverse events compared to adults, possibly due to increased hepatic clearance of the drug. The most prevalent adverse effects in children were found to be gastrointestinal, dermatologic, and neurologic in nature. However, the incidence of severe dermatologic and neurologic adverse events is lower in the pediatric population compared to adults.[12] It use for Chagas in children was approved by the FDA in the US in 2017.[13]

Side effects

Side effects tend to be common and occur more frequently with increased age.[16] The most common adverse reactions associated with benznidazole are allergic dermatitis and peripheral neuropathy.[1] It is reported that up to 30% of people will experience dermatitis when starting treatment.[14][17] Benznidazole may cause photosensitization of the skin, resulting in rashes.[1] Rashes usually appear within the first 2 weeks of treatment and resolve over time.[17] In rare instances, skin hypersensitivity can result in exfoliative skin eruptions, edema, and fever.[17] Peripheral neuropathy may occur later on in the treatment course and is dose dependent.[1] It is not permanent, but takes time to resolve.[17]

Other adverse reactions include anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, insomnia, and dysguesia, and bone marrow suppression.[1] Gastrointestinal symptoms usually occur during the initial stages of treatment and resolves over time.[17] Bone marrow suppression has been linked to the cumulative dose exposure.[17]

Contraindications

Benznidazole should not be used in people with severe liver and/or kidney disease.[16] Pregnant women should not use benznidazole because it can cross the placenta and cause teratogenicity.[14]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Benznidazole is a nitroimidazole antiparasitic with good activity against acute infection with Trypanosoma cruzi, commonly referred to as Chagas disease.[14] Like other nitroimidazoles, benznidazole's main mechanism of action is to generate radical species which can damage the parasite's DNA or cellular machinery.[18] The mechanism by which nitroimidazoles do this seems to depend on whether or not oxygen is present.[19] This is particularly relevant in the case of Trypanosoma species, which are considered facultative anaerobes.[20]

Under anaerobic conditions, the nitro group of nitroimidazoles is believed to be reduced by the pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase complex to create a reactive nitro radical species.[18] The nitro radical can then either engage in other redox reactions directly or spontaneously give rise to a nitrite ion and imidazole radical instead.[19] The initial reduction takes place because nitroimidazoles are better electron acceptors for ferredoxin than the natural substrates.[18] In mammals, the principal mediators of electron transport are NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH, which have a more positive reduction potential and so will not reduce nitroimidazoles to the radical form.[18] This limits the spectrum of activity of nitroimidazoles so that host cells and DNA are not also damaged. This mechanism has been well-established for 5-nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole, but it is unclear if the same mechanism can be expanded to 2-nitroimidazoles (including benznidazole).[19]

In the presence of oxygen, by contrast, any radical nitro compounds produced will be rapidly oxidized by molecular oxygen, yielding the original nitroimidazole compound and a superoxide anion in a process known as "futile cycling".[18] In these cases, the generation of superoxide is believed to give rise to other reactive oxygen species.[19] The degree of toxicity or mutagenicity produced by these oxygen radicals depends on cells' ability to detoxify superoxide radicals and other reactive oxygen species.[19] In mammals, these radicals can be converted safely to hydrogen peroxide, meaning benznidazole has very limited direct toxicity to human cells.[19] In Trypanosoma species, however, there is a reduced capacity to detoxify these radicals, which results in damage to the parasite's cellular machinery.[19]

Pharmacokinetics

Oral benznidazole has a bioavailability of 92%, with a peak concentration time of 3–4 hours after administration.[21] 5% of the parent drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which implies that clearance of benznidazole is mainly through metabolism by the liver.[22] Its elimination half-life is 10.5-13.6 hours.[21]

Interactions

Benznidazole and other nitroimidazoles have been shown to decrease the rate of clearance of 5-fluorouracil (including 5-fluorouracil produced from its prodrugs capecitabine, doxifluridine, and tegafur).[23] While co-administration of any of these drugs with benznidazole is not contraindicated, monitoring for 5-fluorouracil toxicity is recommended in the event they are used together.[24]

The GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide may slow down the absorption and activity of benznidazole, presumably due to delayed gastric emptying.[25]

Because nitroimidazoles can kill Vibrio cholerae cells, use is not recommended within 14 days of receiving a live cholera vaccine.[26]

Alcohol consumption can cause a disulfiram like reaction with benznidazole.[1]

References

- Bern, Caryn; Montgomery, Susan P.; Herwaldt, Barbara L.; Rassi, Anis; Marin-Neto, Jose Antonio; Dantas, Roberto O.; Maguire, James H.; Acquatella, Harry; Morillo, Carlos (2007-11-14). "Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States: A Systematic Review". JAMA. 298 (18): 2171–81. doi:10.1001/jama.298.18.2171. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 18000201. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07.

- "Our Formulary | Infectious Diseases Laboratories | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- "Chagas disease". World Health Organization. March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC - Chagas Disease - Resources for Health Professionals - Antiparasitic Treatment". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- Castro, José A.; de Mecca, Maria Montalto; Bartel, Laura C. (2006-08-01). "Toxic side effects of drugs used to treat Chagas' disease (American trypanosomiasis)". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 25 (8): 471–479. doi:10.1191/0960327106het653oa. ISSN 0960-3271. PMID 16937919.

- Urbina, Julio A. "Nuevas drogas para el tratamiento etiológico de la Enfermedad de Chagas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Treatment for Chagas: Enter Supplier Number Two | End the Neglect". endtheneglect.org. 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Carlier, Yves; Torrico, Faustino; Sosa-Estani, Sergio; Russomando, Graciela; Luquetti, Alejandro; Freilij, Hector; Vinas, Pedro Albajar (2011-10-25). "Congenital Chagas Disease: Recommendations for Diagnosis, Treatment and Control of Newborns, Siblings and Pregnant Women". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 5 (10): e1250. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001250. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3201907. PMID 22039554. Archived from the original on 2017-08-31.

- "Paediatric Benznidazole – DNDi". www.dndi.org. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children 4th list (April 2013) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/93143/EMLc_4_eng.pdf;jsessionid=E14AB3B91001367EBF107EB43C039A0C?sequence=1 retrieved 13 February 2020

- Altcheh, Jaime; Moscatelli, Guillermo; Moroni, Samanta; Garcia-Bournissen, Facundo; Freilij, Hector (2011-01-01). "Adverse Events After the Use of Benznidazole in Infants and Children With Chagas Disease". Pediatrics. 127 (1): e212–e218. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1172. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 21173000. Archived from the original on 2016-02-20.

- "Press Announcements - FDA approves first U.S. treatment for Chagas disease". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Pérez-Molina, José A.; Pérez-Ayala, Ana; Moreno, Santiago; Fernández-González, M. Carmen; Zamora, Javier; López-Velez, Rogelio (2009-12-01). "Use of benznidazole to treat chronic Chagas' disease: a systematic review with a meta-analysis". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 64 (6): 1139–1147. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp357. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 19819909.

- Coronel, María Verónica Pacheco; Frutos, Laura Oriente; Muñoz, Eva Calabuig; Valle, Diana Kury; Rojas, Dolores Hernández Fernández de (February 2017). "Adverse systemic reaction to benznidazole". Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 50 (1): 145–147. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0071-2016.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC - Chagas Disease - Resources for Health Professionals - Antiparasitic Treatment". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Grayson, M. Lindsay; Crowe, Suzanne M.; McCarthy, James S.; Mills, John; Mouton, Johan W.; Norrby, S. Ragnar; Paterson, David L.; Pfaller, Michael A. (2010-10-29). Kucers' The Use of Antibiotics Sixth Edition: A Clinical Review of Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antiviral Drugs. CRC Press. ISBN 9781444147520. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Edwards, David I (1993). "Nitroimidazole drugs - action and resistance mechanisms. I. Mechanism of action". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 31: 9–20. doi:10.1093/jac/31.1.9.

- Eller, Gernot. "Synthetic Nitroimidazoles: Biological Activities and Mutagenicity Relationships". Scientia Pharmaceutica. 77: 497–520. doi:10.3797/scipharm.0907-14. Archived from the original on 2016-11-06.

- Cheng, Thomas C. (1986). General Parasitology. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-12-170755-5.

- Raaflaub, J; Ziegler, WH (1979). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of the trypanosomicide benznidazole in man". Arzneimittelforschung. 29 (10): 1611–1614.

- Workman, P.; White, R. A.; Walton, M. I.; Owen, L. N.; Twentyman, P. R. (1984-09-01). "Preclinical pharmacokinetics of benznidazole". British Journal of Cancer. 50 (3): 291–303. doi:10.1038/bjc.1984.176. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 1976805. PMID 6466543.

- Product Information: Teysuno oral capsules, tegafur gimeracil oteracil oral capsules. Nordic Group BV (per EMA), Hoofddorp, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Product Information: TINDAMAX(R) oral tablets, tinidazole oral tablets. Mission Pharmacal Company, San Antonio, TX, 2007.

- Product Information: ADLYXIN(TM) subcutaneous injection, lixisenatide subcutaneous injection. sanofi-aventis US LLC (per manufacturer), Bridgewater, NJ, 2016.

- Product Information: VAXCHORA(TM) oral suspension, cholera vaccine live oral suspension. PaxVax Inc (per manufacturer), Redwood City, CA, 2016.

External links

- "Rochagan [Patient Information]" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Hoffmann-La Roche. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- "Benznidazole". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.