Battlefield

A battlefield, battleground, or field of battle is the location of a present or historic battle involving ground warfare. It is commonly understood to be limited to the point of contact between opposing forces, though battles may involve troops covering broad geographic areas. Although the term implies that battles are typically fought in a field – an open stretch of level ground – it applies to any type of terrain on which a battle is fought. The term can also have legal significance, and battlefields have substantial historical and cultural value—the battlefield has been described as "a place where ideals and loyalties are put to the test".[1] Various acts and treaties restrict certain belligerent conduct to an identified battlefield. Other legal regimes promote the preservation of certain battlefields as sites of historic importance.

Modern military theory and doctrine has, with technological advances in warfare, evolved the understanding of a battlefield from one defined by terrain to a more multifaceted perception of all of the factors affecting the conduct of a battle and is conceptualised as the battlespace.

Choice of battlefields

The occurrence of a battle at a particular location may be entirely accidental, if an encounter between hostile forces occurs with neither side having expected the encounter. Typically, however, the location is chosen deliberately, either by agreement of the two sides or, more commonly, by the commander of one side, who attempts to either initiate an attack on terrain favorable to the attack, or position forces on ground favorable to defense, if anticipating an attack.

Agreed battlefields

Although many battlefields arise in the course of military operations, there have been a number of occasions where formal conventions have ordained the nature and site of the battlefield. It has been suggested, on the basis of anthropological research, that ritual warfare involving battles on traditional "fighting grounds", bound by rules to minimise casualties, may have been common among early societies.[2]

In the European Middle Ages, formal pre-arrangement of a battlefield occasionally occurred. The Vikings had the concept of the "hazelled field", where an agreed site was marked out with hazel rods in advance of the battle.[3]

Formal arrangements by armies to meet one another on a certain day and date were a feature of Western Medieval warfare, often related to the conventions of siege warfare. This arrangement was known as a journée. Conventionally, the battlefield had to be considered a fair one, not greatly advantaging one side or the other. Arrangements could be very specific about where the battle should take place. For example, at the siege of Grancey in 1434, it was agreed that the armies would meet at "the place above Guiot Rigoigne's house on the right side towards Sentenorges, where there are two trees".[4]

In a pitched battle, although the battlefield is not formally agreed upon, either side can choose to withdraw rather than engaging in the battle. The occurrence of the battle therefore generally reflects the belief by both sides that the battlefield and other circumstances are advantageous for their side.

Geography and the choice of battlefield

Some locations are chosen for certain features giving advantage to one side or another.

In the 1820s, General Joseph Rogiat, of Napoleon Bonaparte's Grande Armée, spoke at great length of the circumstances that make for a good battlefield. He divided the battlefield in two: one favorable for attack and one for defense, and argued that the greater the benefit of one over the other, the stronger a position was.[5] He went on to say that easy movement of troops to the front, and distribution of forces across the front, was also important, since this allowed support and reinforcement as needed. He mentions the high ground as a means of observing the enemy, and concealing friendly forces;[5] while this has been mitigated by aerial reconnaissance, improved communication (field telephone and radio), and indirect fire, it remains important. (For instance, "hull down" firing positions for tanks were desired well into World War Two.)

Rogiat also discussed cover, in reference to exposure to cannon fire; in earlier times, it would have been to slingers (in Ancient Greek and Roman times) or archers (such as the Welsh longbowmen or Mongol horse archers) from ancient times well into the 1400s, while slightly later, it would be to riflemen.)

Rogniat describes a "disadvantageous field of battle" as one:

which is everywhere seen and commanded from heights within cannon and musket shot, and which is encumbered with marshes, rivers, ravines, and defiles of every kind. The enemy moves upon it with difficulty, even in column; he cannot deploy for the contest, and is made to suffer under a shower of projectiles without being able to return evil for evil.[5]

This may be called an ideal defensive position, however. He then advises that troops should be situated so that the ground they defend is favorable, while the ground through which the enemy must advance is unfavorable:

A position which combines these two kinds of fields of battle is doubly strong, both by its situation, and by the obstacles which cover it. But if it fulfils only one of these conditions, it ceases to be easy of defence. Suppose that a position, for instance, offers to the defenders a field of battle well situated, but admitting of easy access upon all points; the assailants, finding no obstacle to their deployment for the contest, will be able to force it in a tolerably short time. Suppose another position presents to the assailants a field of battle abounding with obstacles and defiles, but without offering at the same time, in the rear, favourable ground for the deployment of the defenders; these could then only act upon it with difficulty, and would be forced to fight the assailants in the defiles themselves, without any advantage. In general, the best positions are those, the flanks of which are inaccessible, and which command from their front a gently inclined ground, favourable for attack as well as defence; farther, if the lines lean on villages and woods, each of which forms, by its saliency, a sort of defensive bastion, the army becomes almost impregnable, without being reduced to inaction.[5]

During World War One, for instance, the An Nafud behind Aqaba seemed impassible, until a force of Arab rebels led by T. E. Lawrence successfully crossed it to capture the town. In World War Two, the Pripyat Marsh was an obstacle to vehicles, and the Red Army successfully employed cavalry there specifically because of that, while in North Africa, the Qattara Depression was used as an "anchor" for a defensive line.

The belief that a location is impregnable will lead to it being chosen for a defensive position, but may produce complacency. During the Jewish Rebellion in 70 AD, Masada was thought to be unassailable; determined Roman military engineering showed it was not. In World War One, Aqaba was considered safe. During World War Two, Monte la Difensa was revealed to be vulnerable by the First Special Service Force. (All three instances would later be used in films.)

Crossing obstacles remains a problem. Even a seemingly open field, such as that faced by George Pickett at Gettysburg, was broken by fences which had to be climbed—while his division was constantly exposed to fire from the moment it left the trees. On modern battlefields, introducing obstacles to slow an advance has risen to an art form: everything from anti-tank ditches to barbed wire to dragon's teeth to improvised devices, have been employed, in addition to minefields. The nature of the battlefield influences the tactics used; in Vietnam, heavy jungle favored ambush.

Historically, military forces have sometimes trained using methods suitable for a level battlefield, but not for the terrain in which they were likely to end up fighting. Mardonius illustrated the problem for the Ancient Greeks, whose phalanges were ill-suited for combat except on level ground without trees, watercourses, ditches, or other obstacles that might break up its files,[6] a perfection rarely obtained. Rome had the same preference.[6] By the 20th Century, many military organizations had specialist units, trained to fight in particular geographic areas, like mountains (Alpine units), desert (such as the LRDG), or jungle (such as Britain's Chindits and later U.S. Special Forces), or on skis. Others were trained for delivery by aircraft (air portable), glider, or parachute (airborne); after the development of helicopters, airmobile forces developed. The increasing number of amphibious assaults, and their particular hazards and problems, led to the development of frogmen (and later SeALs). These specialist forces opened up new fields of battle, and added new complexities to both attack and defense: when the battlefield ceased to be physically connected to the supply base, as at Arnhem, or in Burma, or in Vietnam, the geography of the battlefield could not only dictate how a battle was fought, but with what weapons, and both reinforcement and logistics could be critical. At Arnhem, for instance, there were failures in both, while in Burma, aerial supply deliveries enabled the Chindits to do something that would otherwise have been impossible. Armies generally avoided fighting in cities, when possible, and modern armies dislike giving up the freedom of maneuver; as a result, when compelled to fight for control of a city, such as Stalingrad or Ortona, weapons, tactics, and training are ill-suited for the environment. Urban combat is the one specialty that has not yet arisen.

Technology and the choice of battlefield

New technologies also affect where battles are fought. The adoption of chariots makes flat, open battlefields desirable, and larger fields than for infantry alone, as well as offering opportunities to engage an enemy sooner.

During the American Civil War, rail transport influenced where and how battles would be, could be, fought, as did telegraphic communication. This was a major factor in the execution of the German invasion of France in WW1: German forces could only travel as far from railheads as their ability to transport fodder allowed; the ambitious plan was doomed before it launched. Single battles, such as Cambrai, can depend on the inception of new technology, such as (in this instance) tanks.

The synergy between technologies can also affect where battles take place. The arrival of aerial reconnaissance has been credited with the development of trench warfare, while the combination of high explosives in ammunition and hydraulic recoil mechanisms in artillery, added to aircraft observation, made its subsequent spread necessary, and contributed to the stalemate of WW1. The proliferation of tanks and aircraft changed the dynamics again in WW2.

In both Burma in World War Two, and in Vietnam, air supply played an important part in where battles took place. Some, such as Arnhem or the A Sầu, would not have happened at all, absent the development of aircraft and helicopters. So, too, has the introduction of landing craft; combined with naval gunfire support, they have made beach landings the site of battles, where, in ancient times, the very idea of contesting a landing was unheard of.

The Vietnamese preference for ambush against a more sophisticated opponent was a function of less access to sophisticated technology.

As much as technology has changed, terrain still cannot be ignored, because it not only affects movement on the battlefield, but movement to and from it, and logistics are critical: a battlefield, in the industrial age, may be a railway line or a highway As technology grows more sophisticated, the length of the "tail", upon which the troops at the front depend, gets longer, and the number of places a battle can be decided (beyond the immediate point of contact) grows.

Legal implications

The concept of the battlefield arises at various points in the law of war, the international law and custom governing geographic restrictions on the use of force, taking of prisoners of war and the treatment afforded to them, and seizure of enemy property. With respect to the seizure of property, it has been noted that in ancient times it was understood that a prevailing enemy was free to take whatever was left on the battlefield by a fleeing enemy—weapons, armor, equipment, food, treasure—although, customarily, "capture of booty may take place some distance from the battlefield; it may transpire a few days after the battle, and it may even occur in the total absence of any pitched battle".[7]

Historic battlefields

Location

The locations of ancient battles can be apocryphal. In England, this information has been more reliably recorded since the time of the Norman conquest.[1] Battles are usually named after some feature of the battlefield geography, such as the name of a town, forest or river, commonly prefixed "Battle of...", but the name may poorly reflect the actual location of the event. Where documentary sources describe a battle, "whether such references are contemporary or reliable needs to be assessed with care".[1] Locating battlefields is important in attempts to recreate the events of battles:

The battlefield is a historical source demanding attention, interpretation and understanding like any written or other account. To understand a battle, one has to understand the battlefield.[8]

Battlefield preservation

Many battlefields from specific historic battles are preserved as historic landmarks.[9]

The study area of a battlefield includes all places related to contributing to the battle event: where troops deployed and maneuvered before, during, and after the engagement; it is the maximum delineation of the historical site and provides more of the tactical context of a battle than does the core area. The core area of a battlefield is within the study area and includes only those places where the combat engagement and key associated actions and features were located; the core area includes, among other things, what often is described as "hallowed ground".[10]

A battlefield is typically the location of large numbers of deaths. Given the intensity of combat, it may not be possible to easily retrieve bodies from the battlefield leading to the observation that "[a] battlefield is a graveyard without the gravestones".[11]

Battlefield commemoration

Battlefields can host memorials to the battles that took place there. These might commemorate the event itself or those who fell in the battle. This practice has a long history. It was common among the Ancient Greeks and Romans to raise a trophy on the field of battle, initially of arms stripped from the defeated enemy. Later these trophies might be replaced by more permanent memorials in stone or bronze.[12]

Another means by which historic battles are commemorated is historical reenactment. Such events are typically held at the location of the original battle, but if circumstances make that inconvenient, reenactors may replicate the battle in an entirely different location. For example, in 1895, members of the Gloucestershire Engineer Volunteers reenacted their famous stand at Rorke's Drift in Africa, 18 years earlier, with the reenactment occurring at the Cheltenham Winter Gardens in England.[13] The first documented Korean War reenactment was held in North Vernon, Indiana, by members of the 20th Century Tactical Studies Group portraying Canadian and North Korean troops, on March 15, 1997.[14]

Gallery of battlefield images

Reenactors at a 2011 reenactment of the Battle of Marathon, which occurred in 490 BC.

Reenactors at a 2011 reenactment of the Battle of Marathon, which occurred in 490 BC.- A 2006 reenactment of the Battle of Hastings, which occurred in 1066.

American Revolutionary War artillery on display at the site of the 1781 Siege of Yorktown.

American Revolutionary War artillery on display at the site of the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. Painting of the defeat of the Russian Trinity Infantry Regiment in the Battle of Sultanabad, in 1812.

Painting of the defeat of the Russian Trinity Infantry Regiment in the Battle of Sultanabad, in 1812. Illustration of two nurses treating a soldier on the battlefield during the Franco-Prussian War, c. 1870.

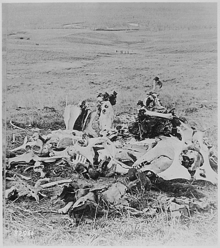

Illustration of two nurses treating a soldier on the battlefield during the Franco-Prussian War, c. 1870. A pile of bones, including those of cavalry horses, on the battlefield of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in 1876.

A pile of bones, including those of cavalry horses, on the battlefield of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in 1876._landed_on_eastern_side_of_Guantanamo_Bay%2C_Cuba_on_10_June_1898.jpg) First Marine Battalion (United States) hoisting the flag at the Battle of Guantánamo Bay during the Spanish–American War, in 1898.

First Marine Battalion (United States) hoisting the flag at the Battle of Guantánamo Bay during the Spanish–American War, in 1898. Iraqi armored personnel carriers, tanks and trucks destroyed in a Coalition attack along a road in the Euphrates River Valley during Operation Desert Storm, in 1991.

Iraqi armored personnel carriers, tanks and trucks destroyed in a Coalition attack along a road in the Euphrates River Valley during Operation Desert Storm, in 1991.

See also

| Look up battlefield or battleground in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battlefields. |

- Battlefield archaeology

- Battlespace

- Virtual battlefield

References

- Veronica Fiorato, Anthea Boylston, Christopher Knüsel, Blood Red Roses: The Archaeology of a Mass Grave from the Battle of Towton AD 1461 (2007), p. 3.

- Keegan, John (1993). A History of Warfare. London: Hutchinson. pp. 98–103. ISBN 0091745276.

- Paddy, Griffith (1995). The Viking Art of War. London: Greenhill Books. p. 118. ISBN 1853672084.

- Keen, Maurice (1965). The Laws of War in the Late Middle Ages. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 129.

- Joseph Rogniat (général de division), quoted in The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine (1829), p. 160.

- Philip Sabin, Hans van Wees, Michael Whitby, The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare (2007), p.

- Yoram Dinstein, "Booty in Warfare", in Frauke Lachenmann, Rüdiger Wolfrum, editors, The Law of Armed Conflict and the Use of Force: The Max Planck Encyclopedia (2015), p. 141.

- Rayner, Michael, ed. (2006). Battlefields:Exploring the Arenas of War 1805-1945. London: New Holland. p. 8. ISBN 978-1845371753.

- United States National Park Service, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield: Final General Management Plan (2003), p. 169.

- Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report (1994), p. 54.

- Richard Lusardi, quoted in Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Draft General Management Plan (2003), p, 169.

- Jutta Stroszeck, "Greek Trophy Monuments," in Myth and Symbol II: Symbolic Phenomena in Ancient Greek Culture, ed. Synnøve des Bouvrie, The Norwegian Institute at Athens (2004), p.303

- Howard Giles. "A Brief History of Re-enactment".

- Battle Cry: The Newspaper of Reenacting' Vol. 3, no. 2, Summer, 1997.