Battle of Trapani

The Battle of Trapani took place in 1266 off Trapani, Sicily, between the fleets of the Republic of Genoa and the Republic of Venice, as part of the War of Saint Sabas. The Genoese had an advantage in numbers, but the Genoese commander, Lanfranco Borbonino, ordered his ships to take up a defensive position, bound together with chains, near the shore. As the Venetian fleet attacked, many of the Genoese ships' crews, composed in large part of hired foreigners, lost heart and abandoned their ships. The battle was a crushing Venetian victory, as they captured the entire Genoese fleet almost intact. On their return to Genoa, Borbonino and most of his captains were tried and fined large sums for cowardice.

Background

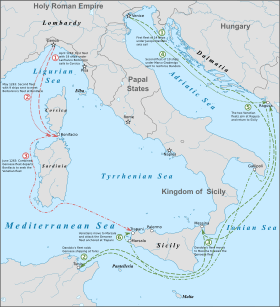

The War of Saint Sabas between the rival Italian maritime republics of Venice and Genoa broke out over access to and control of the ports and markets of the Eastern Mediterranean. In the Battle of Acre in 1258 and again in the Battle of Settepozzi in 1263, the Venetian navy had demonstrated its superiority over its Genoese counterpart.[1][2] Consequently the Genoese avoided direct confrontations with the Venetian battle fleet and engaged in commerce raiding against the Venetian merchant convoys, a type of warfare exemplified by the Battle of Saseno in August 1264, when the annual Venetian trade convoy (muda) to the Levant was captured by the Genoese.[3][4]

At the same time, the Venetians' diplomatic position improved, as the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, broke his treaty of alliance with Genoa, due to the poor Genoese performance against Venice. In 1264, he expelled the Genoese from Constantinople and sought a rapprochement with Venice that culminated in a provisional non-aggression pact in 1265, although it was not finally ratified until three years later.[5][6] At sea, 1265 saw no major combat at sea, and the fleet of 16 galleys under Giovanni Delfino successfully escorted the year's trade convoy to Syria and back to Venice. The Genoese fleet of ten galleys, under Simone Guercio, had tarried in sailing, so that the Venetians were already back in the Adriatic Sea.[7] According to the naval historian Camillo Manfroni, there were several reasons why warfare was conducted in such an almost desultory manner: both sides faced severe financial shortages,[8] and furthermore, were confronted with the landing of the ambitious Charles I of Anjou in Italy, leading both naval powers to adopt a cautious stance.[7]

Opening moves

For the 1266 raiding campaign, Genoa prepared a fleet comprising eighteen galleys and a large nave,[lower-alpha 1] under Lanfranco Borbonino. As the fleet departed for Corsica in late April, news arrived of increased Venetian naval strength, and nine more galleys were ordered into action; they joined the rest of the fleet at Bonifacio later in May.[10][11]

In reality, the Venetian fleet only counted 15 galleys according to the Venetian chronicler Martino da Canal (the Annali Genovesi report only ten).[10][11] Jacopo Dondulo (often erroneously called Dandolo), an experienced sailor who was said to "know the harbours and holes where the Genoese lay in hiding", was appointed as its commander.[12][13] Due to financial constraints, the bulk of the fleet was to be furnished by the Venetian colonies—four from Crete, three from Zara, and three galleys and a galleot from Negroponte—while only four galleys were to be equipped in Venice itself. [8][12]

Dondulo led his fleet to Tunis, where they captured a Genoese ship in a night attack, removed its crew and cargo, and burned it. The next day, a small merchant vessel from Savona was likewise captured, while on the way back to Messina, the Venetians encountered and defeated a pirate squadron of two galleys and a saetta[lower-alpha 2] from Porto Venere, capturing one of the galleys with most of its crew.[10][11]

The Venetians may have hoped to encounter the Genoese battle fleet at or near the Straits of Messina, but luckily for them, given the actual correlation of forces, the Genoese remained at Bonifacio. The Venetians, after unloading their booty at Messina, set sail for Venice. In the meantime, however, news had reached Venice of the large Genoese fleet, and a further ten galleys under the veteran commander Marco Gradenigo had been dispatched to join with Dondulo. The two squadrons met at Ragusa, and their commanders decided to return to Sicily to search for the Genoese fleet.[10][15] Faced with the apparent inactivity of the Genoese fleet, which recalled the previous year, many of the Venetian patricians serving with the fleet were growing anxious to leave so that they could participate in the summer trade convoy which would soon depart for the Levant, so the Venetian fleet had to stop at Apulia—likely at Gallipoli—and allow them to disembark and make their way to Venice over land.[16][17]

Battle

In the meantime, Borbonino received reports that the Venetians had assembled thirty galleys or even more, whereas in reality he had a slight numerical advantage. As a result, he decided to abandon the nave, and distribute its crew to the other vessels to enhance their combat strength. Finally, in early June Borbonino led his fleet out of Bonifacio to confront the Venetians.[18] On 22 June, the Genoese were at Trapani, when they received intelligence that the Venetian fleet was at Marsala nearby, and that it was smaller than Borbonino had feared. Borbonino convened a council of war with his three councillors and the galley captains. The Genoese captains did not trust their crews, many of whom, according to the sources, were Lombards and other foreigners hired as substitutes by Genoese citizens eager to avoid the hardships and dangers of rowing in a war galley. As a result, the council resolved to attack the Venetians from the direction of the open sea, so that the crews would not be tempted to abandon their posts and swim for the shore.[18][19][17]

However, soon Borbonino decided otherwise. Possibly influenced by previous Venetian victories in open combat, he decided to adopt a purely defensive position, chaining his ships together, with their sterns turned to the safety of the shore, and their prows directed seaward. This tactic offered many advantages to the defender, especially, according to historian John Dotson, "in the face of a more skillful, aggressive opponent": it ensured that his fleet would not be flanked or split apart, and that reinforcements could be quickly moved to any threatened ship. On the other hand, it presupposed that the defenders would possess discipline and steadfastness.[18][20] To further bolster his crews, Borbonino hired large numbers of local Trapanese, offering them one gold agostaro coin per day.[21]

Borbonino's order was carried out during the night, and when, next day, the Venetian fleet arrived at Trapani, they found the Genoese galleys bound and chained together. Taking this as a sign of poor morale among their opponents, and despite the contrary wind, the Venetians eagerly advanced upon them Genoese, raising loud shouts to further discourage them.[22][12][23] Twice the Venetian attempts to break the Genoese line failed, but on the third attempt they succeeded in detaching three Genoese galleys from the main body. The Genoese had tried to counter the Venetian attacks by setting a burning raft adrift against their enemy's ships, but when they saw the Venetian success, panic began to spread among the Genoese crews.[24][25] Already disheartened by their commander's apparent lack of confidence, the Genoese began to abandon their ships and swim ashore to safety, so that in the end the Venetians were able to capture all 27 Genoese galleys, as well as some of the crews who remained behind. 24 of them were towed away, while three were burned on the spot. Some 1,200 Genoese drowned, many were killed, and 600 were taken captive.[24][25][26]

Aftermath

Borbonino and his officers were able to escape, but on their return to Genoa they were tried and, except for five, were found guilty of cowardice and incompetence. Their possessions were confiscated and large fines were imposed on them.[26][27] Indeed, while Da Canal provides a vivid and detailed account of the battle, the Annali Genovesi simply report that the Genoese crews abandoned their ships, almost as soon as the Venetians were sighted. As Manfroni comments, the Genoese government and its chronicler were probably eager to put the entire blame of the defeat on Borbonino's shoulders and excuse the disaster through his supposed cowardice.[27]

Dondulo was acclaimed a hero on his return to Venice in July, towing the captured ships, and was duly elected as Captain-General of the Sea.[13] He soon fell out with Doge Reniero Zeno, however: the Doge insisted that the fleet restrict itself to escorting the merchant convoys, whereas Dondulo strongly supported the idea that the fleet should, rather than return to Venice once the convoys were safely under way, remain at sea seeking to attack Genoese shipping. As a result of this disagreement, Dondulo resigned and was replaced by his lieutenant, Marco Zeno.[13]

The Venetian triumph at Trapani did not immediately impact the course of the war.[20] Genoa was still more than capable of quickly replenishing its losses. Already in August another fleet of 25 ships under Oberto D'Oria set sail and made for the Adriatic, while the victorious Venetian fleet remained at Venice, its inactivity prolonged by the squabbles between Dondulo and the Doge.[28]

Marco Zeno's cautious leadership and strict adherence to the Doge's orders left the seas open to the Genoese raiders.[13] D'Oria moved east and sacked the town of Canea on Crete sometime in September. On his return journey, his fleet encountered the Venetian trade convoy sailing east, protected by Zeno's thirty galleys. Numerically inferior and encumbered with the loot and captives of Canea, D'Oria avoided combat and fled. Despite having the advantage over his enemy, Zeno was content to see the Genoese retreating, and did not pursue them.[28] As a result, in spring 1267, Dondulo was recalled to command. This time he carried out his chosen strategy, keeping the fleet at sea and attacking the Genoese fleet that was blockading Acre in August. The Genoese again tried to escape, so that the Venetians only captured five ships; and when the two fleets met again at Tyre, the Genoese again refused to offer battle and escaped.[13]

The stalemate between the two powers continued, until in 1269 King Louis IX of France, keen to use the Venetian and Genoese fleets in his planned Eighth Crusade, coerced both to sign a five-year-truce in the Treaty of Cremona.[20][29] This truce would hold and be renewed a number of times, until the heightening of Genoese–Venetian antagonism in the wake of the conquest of the last Western outposts in the Levant by the Mamluks of Egypt led both powers to the War of Curzola in 1294.[30]

Notes

- A nave, plural navi, was a type of large, broad-beamed cargo vessel equipped with lateen sails. Due to their size, high sides, and capacity to carry hundreds of marines, and even siege engines, they were almost impossible to defeat in battle except by another nave.[9]

- A saetta, plural saette, was a type of smaller and narrower galley, with only one oarsman per bench rather than two or three, optimized for speed rather than carrying capacity.[14]

References

- Stanton 2015, pp. 160–163.

- Dotson 1999, pp. 167–168.

- Stanton 2015, pp. 163–164.

- Dotson 1999, pp. 168–176.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 18–19, 30.

- Wiel 1910, pp. 175–176.

- Manfroni 1902, p. 19.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 19–20.

- Dotson 2006, pp. 65–67.

- Dotson 1999, p. 176.

- Manfroni 1902, p. 20.

- Wiel 1910, p. 174.

- Pozza 1992.

- Dotson 2006, pp. 65–66.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 20–21.

- Dotson 1999, pp. 176, 178.

- Manfroni 1902, p. 21.

- Dotson 1999, p. 178.

- Stanton 2015, pp. 164–165.

- Stanton 2015, p. 165.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 21–22.

- Dotson 1999, pp. 178, 179.

- Manfroni 1902, p. 22.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 22, 23.

- Wiel 1910, p. 175.

- Dotson 1999, p. 179.

- Manfroni 1902, pp. 22–23.

- Manfroni 1902, p. 24.

- Wiel 1910, p. 176.

- Stanton 2015, pp. 165–166.

Sources

- Dotson, John E. (1999). "Fleet Operations in the First Genoese-Venetian War, 1264-1266". Viator. Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 30: 165–180. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.300833. ISSN 0083-5897.

- Dotson, John E. (2006). "Ship Types and Fleet Composition at Genoa and Venice in the Early Thirteenth Century". In Pryor, John (ed.). Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 30 September to 4 October 2002. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 63–76. ISBN 978-0-7546-5197-0.

- Manfroni, Camillo (1902). Storia della marina italiana, dal Trattato di Ninfeo alla caduta di Costantipoli (1261–1453) [History of the Italian Navy, from the Treaty of Nymphaeum to the Fall of Constantinople (1261–1453)] (in Italian). Livorno: R. Accademia navale. OCLC 265927738.

- Pozza, Marco (1992). "DONDULO, Giacomo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 41: Donaggio–Dugnani (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Stanton, Charles D. (2015). Medieval Maritime Warfare. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-5643-1.

- Wiel, Alethea (1910). The Navy of Venice. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company. OCLC 4198755.