Battle of Ronas Voe

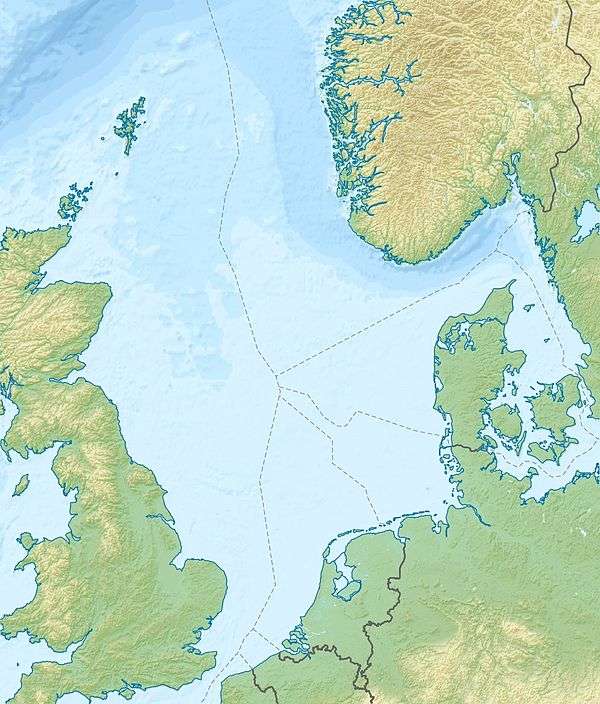

The Battle of Ronas Voe was a naval engagement between the English Royal Navy and the Dutch East India ship Wapen van Rotterdam on 14 March 1674 in Ronas Voe, Shetland as part of the Third Anglo-Dutch War. Having occurred 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster, it is likely to have been the final battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

Shortly after embarking on a journey towards the Dutch East Indies with trade goods and a company of soldiers, extreme weather conditions caused Wapen van Rotterdam to lose its masts and rudder and it was forced to take shelter in Ronas Voe for a number of months. A whistleblower in Shetland informed the English authorities of the ship's presence, and in response three Royal Navy men-of-war and a dogger were dispatched to capture the ship. After a short battle, the ship was captured and taken back to England as a prize of war.

An unknown number of up to 300 of the ship's crew were killed in the battle and were buried nearby in Heylor. A modern memorial to the Dutch crew is erected where they are believed to be buried, bearing the inscription "The Hollanders' Graves".

Background

.jpg)

Wapen van Rotterdam[lower-roman 1] was an East Indiaman with a capacity of 1,124 tons[1] and between 60[2] and 70[3] guns. On 16 December 1673, it departed the Texel bound for the Dutch East Indies[1] with both trade goods and a company of soldiers from the Dutch East India Company's private army, along with an army captain.[4] The ship itself was captained by Jacob Martens Cloet.

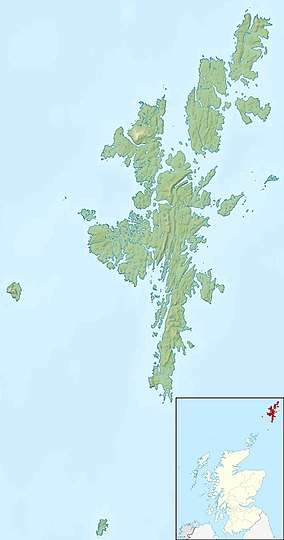

To avoid conflict with the English (with whom, due to the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch were at war), rather than passing through the English Channel, the ship was directed northwards where the plan would be to sail around the north of the British Isles (known as "going north about", which was commonly practised by Dutch East India ships at that time),[5] before heading southwards again.[6] Due to the extreme weather conditions in its journey northwards, the ship lost its masts and rudder,[7][8] and southerly winds prevented the ship from being able to pass through either the Pentland Firth or the Fair Isle Channel, so the ship was (probably with considerable difficulty)[6] taken into Ronas Voe in the north-west of Northmavine, Mainland, Shetland to shelter until the weather improved,[2] and to allow the ship to be repaired.[6] The voe (Shetland dialect for an inlet or fjord)[9] forms a crescent shape around Ronas Hill, which would have allowed the ship to lie sheltered regardless of the direction of the wind.[10] A combination of prevailing southerly winds,[6] and, presumably, a scarcity of suitable wood available in Shetland at that time to replace its masts[11][12][lower-roman 2] prevented the ship from continuing its journey, and as such it remained in Ronas Voe until March 1674.[14]

During their stay, the crew of the ship would have most likely traded Dutch goods such as Hollands gin and tobacco (and perhaps also goods on the ship originally destined for the Dutch East Indies) with the Shetlanders, in exchange for local foodstuffs available at that time, such as kale,[15] meal and mutton – either fresh or reestit.[6] The Shetlanders probably would have had quite a lot in common with the Dutch.[16] The native language of the local Shetlanders at that time would have been Norn, though English would have been understood and used fluently by most.[17] Many Shetlanders (of both the affluent and Commoners) were also fluent in Dutch, despite never having never left Shetland, due to the amount of trade done by Dutch ships in Shetland's ports,[18] as well as with German traders of the Hanseatic League.[19]

From 1603, the Kingdoms of England, Ireland and Scotland had all shared the same monarch with the Union of the Crowns, who by 1674 was Charles II. As such, Scotland was actively involved in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, despite not being included in the conflict's name.[20] Shetland, being a part of the Kingdom of Scotland, was therefore at war with the Dutch, however the local Shetland residents of Heylor and adjacent areas in direct contact with the Dutch may not have been aware of the conflict, and would not have considered the visitors as "enemies".[6] A letter must have been sent by someone with an understanding of the political situation (most likely a laird, minister, merchant, or some other member of the gentry in Shetland) to inform the authorities of the Dutch ship's presence,[6] and that it could not proceed due to it losing its masts and rudder.[8] As a result, a total of four Royal Navy ships – HMS Cambridge,[21] captained by Arthur Herbert (later the Earl of Torrington);[22] HMS Newcastle,[23] captained by John Wetwang (later Sir John Wetwang);[24] HMS Crown,[25] captained by Richard Carter;[26] and Dove,[27] captained by Abraham Hyatt[28] – were ordered to set sail for Shetland and to capture the ship.

Call to arms

_-_02.jpg)

Captain Herbert (Cambridge) was the first to receive his orders in a letter sent 21 February [O.S. 11 February] 1674 by the Royal Navy's Chief Secretary to the Admiralty Samuel Pepys.[29] He stated the orders were "at the desire of the Royal Highness", and stressed that the orders were to be carried out swiftly, as the Treaty of Westminster concluding the war was expected to be published within eight days, and any subsequent hostilities were to last no longer than twelve days.[29] The Treaty of Westminster had in fact been signed two days prior to this letter being sent, and was ratified in England the day before the letter was sent.[30]

The following day letters were sent to both Captains Wetwang (Newcastle) and Carter (Crown) enclosing the same orders.[31] Pepys also wrote again to Captain Herbert (Cambridge) to convey he had arranged for a pilot knowledgeable of Shetland's coast to be sent to him, as well as to inform him that Crown and Dove would accompany his ship.[32]

On 25 February [O.S. 15 February] Captain Herbert (Cambridge) wrote to Pepys to inform him that neither the pilot nor Dove had yet arrived. Pepys replied on 28 February [O.S. 18 February] to say he had sent instruction to hasten the pilot, and had enquired into Dove's delay.[33]

On 3 March [O.S. 21 February] Captain Taylor stationed at Harwich wrote to Pepys to inform him that Cambridge and Crown had passed by on their way to Shetland.[34] The same day, Pepys replied to a letter from Carter (Crown) to inform him that his five weeks' supply of victuals were enough to support his crew until their return from Shetland.[35]

On 6 March [O.S. 24 February], Dove was wrecked on the coast of Northumberland on the journey northwards, leaving the three remaining ships to continue towards Shetland.[27]

Battle

The battle is commonly reported to have occurred in February 1674,[1][2][37][6] however the only known extant contemporary report of the battle indicates that it occurred on 14 March [O.S. 4 March] 1674.[14] This was one day after Pepys' original twenty day deadline for the completion of his orders sent to Captain Herbert,[29] and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster.[30]

Upon their arrival, Cambridge, Newcastle and Crown entered Ronas Voe, where a short, one-sided battle ensued.[6] While a single East Indiaman might have stood a chance, however small, against three much more manoeuvrable men-of-war on open seas, in the confined space of Ronas Voe and most likely still without replacement masts (evidenced by the fact the ship had not left Ronas Voe), Wapen van Rotterdam was completely outmatched.[6]

It is recorded that Newcastle captured Wapen van Rotterdam, and it was taken back to England as a prize of war.[10][4] A contemporary Dutch newspaper reported that while 400 crew were originally on board Wapen van Rotterdam, later only 100 prisoners were being transported by Crown,[14] suggesting up to 300 crew may have been killed, although additional prisoners might have been transported on the other English ships. Those killed in the battle were buried nearby in Heylor.[16] Both Cloet and the army captain survived the battle and were taken back to England with the rest of the surviving crew.[4]

Aftermath

Crown took aboard one hundred Dutch prisoners. When the ship returned to England, it experienced extremely bad weather (in which it was reported that 10 valuable ships between Great Yarmouth and Winterton-on-Sea had to be stranded, some of which were destroyed) and was unable to land before it reached Dover on 29 March [O.S. 19 March] 1674.[14] Samuel Pepys wrote to Captain Carter (Crown) on 31 March [O.S. 21 March], telling him "His Majesty and his Royal Highness are well pleased with his account of the good success of the Cambridge and Newcastle."[38] The ships returned to the Downs by 3 April [O.S. 24 March].[10] Pepys wrote to Captain Herbert (Cambridge) on 4 April [O.S. 25 March] and passed on that the Lords had commented, "Long may the civility which you mention of the Dutch to his Majesty's ships continue."[39]

Captain Wetwang directed the Dutch ship to Harwich on 7 April [O.S. 28 March] en route to the River Thames.[4] The remaining Dutch crew were put ashore in Harwich, after which Cloet and the army captain set sail back to the Dutch Republic in a packet boat.[4] Before departing, the Dutch captains valued Wapen van Rotterdam (and presumably also the trade goods on board) at approximately £50,000[4] – equivalent to £7,300,000 in 2019. In June the same year, the Lord Privy Seal Arthur Annesley asked the Principal Commissioners of Prizes and the Lord High Treasurer to award Captain Wetwang £500 – equivalent to £73,000 in 2019 – for his capture of the ship and its safe return to the Thames. This prize was to be funded from the sale of the goods aboard the ship, or if the value raised was insufficient to fund this prize, the Privy Seal instructed the Lord High Treasurer "to find out some other proper way for payment thereof, as a free gift."[40]

Letters carried by Wapen van Rotterdam were captured, and still survive in the English admiralty archives. They were partly published in 2014.[41]

Goods put up for sale

On 24 May [O.S. 14 May] 1674, many of the goods aboard the ship were put up for sale at the East India House, City of London:

| Item | Quantity | Notes | Maximum total sale value[lower-roman 3] | Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Metric equivalent

(approx) |

1674 value | Equivalent value

(2019) | |||||

| £ | s | d | ||||||

| Scarlet | 229 yards | 209 Metres | 148 | 17 | 0 | £21,601 | [42] | |

| Crimson cloth | 234 yards | 214 metres | 140 | 8 | 0 | £20,375 | ||

| Crimson cloth | 209 yards | 191 metres | 83 | 12 | 0 | £12,132 | ||

| Red cloth | 223 yards | 204 metres | 78 | 1 | 0 | £11,327 | ||

| Scarlet and crimson cloth | 41 yards | 37 metres | 3 remnants | 20 | 10 | 0 | £2,975 | |

| Amber | 2 small cases | |||||||

| Mum brown Hollands beer | 180 barrels | 28,281 Litres | Sale programme states "or what it is" | 120 | 0 | 0 | £17,415 | |

| Spanish wine | 10 leadgers and 1 puncheon | Sale programme states "or what it is" | ||||||

| Rhenish wine | 8 leadgers | |||||||

| Vinegar | 21 puncheons | 6,636 – 6,720 litres | 84 | 0 | 0 | £12,190 | ||

| Rack | 5 rundlets | 340 litres | 6 | 0 | 0 | £871 | ||

| Butter | 4 firkins | 100 Kilograms | In barrels of pickle | 4 | 12 | 0 | £668 | |

| Oil | 15 rundlets | 1,020 litres | 27 | 0 | 0 | £3,918 | ||

| Malay language New Testaments | 220 | 11 | 0 | 0 | £1,596 | |||

| Small Books | 6 bundles | 6 | 13 | 8 | £969 | |||

| Prayer books | 283 | |||||||

| Rushes | 150 bundles | 1 | 17 | 6 | £273 | |||

| Prunes | 10 drum hogsheads and 1 butt | |||||||

| Glue | 2 tierces | 316–320 litres | ||||||

| Spruce beer | 40 gallons | 185 litres | Among 3 rundlets | 5 | 0 | 0 | £726 | |

| Isinglass | 2 cases | |||||||

| Round shaves | 47 | 1 | 11 | 4 | £228 | [43] | ||

| Howells | 42 | 1 | 1 | 0 | £152 | |||

| Percers | 192 | 2 | 8 | 0 | £348 | |||

| Gilt leaf | 5 boxes | 1 | 0 | 0 | £145 | |||

| Iron plates | 100 | |||||||

| Tew irons cast for bellows | 20 | |||||||

| Beak irons for smiths | 5 | |||||||

| Pairs of wooden screws | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | £145 | |||

| Copper Kettles | 23 | |||||||

| Copper plates or bottoms | 21 | |||||||

| Pairs of pinchers | 75 | 0 | 18 | 9 | £136 | |||

| Drills | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | £36 | |||

| Small Brushes | 100 | 0 | 12 | 6 | £91 | |||

| Carpenters' brass compasses | 156 | With iron points | 6 | 10 | 0 | £943 | ||

| Iron collars or turners | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0 | £65 | |||

| Handvices | 36 | 1 | 16 | 0 | £261 | |||

| Brass cocks | 30 | 1 | 10 | 0 | £218 | |||

| Small cabin Bells | 30 | |||||||

| Sea compasses | 49 | 6 | 2 | 6 | £890 | |||

| Square Glasses for compasses | 34 | 0 | 4 | 3 | £30 | |||

| Cards for compasses | 72 | 1 | 4 | 0 | £174 | |||

| Round glasses for compasses | 18 | 0 | 1 | 6 | £12 | |||

| Half-hour glasses | 46 | 0 | 15 | 4 | £112 | |||

| Cardis | 1 chest | 1 | 11 | 0 | £225 | |||

| Wormwood | 1 chest | 1 | 11 | 0 | £225 | |||

| Roots | 1 cask | In sand | 1 | 11 | 0 | £225 | ||

| Empty cases lined with sheet lead | 4 | 1 | 11 | 0 | £225 | |||

Remaining goods

Those goods still remaining on the ship following the sale, along with the sails and cables not offered for sale were catalogued and stored at his Majesties stores in Woolwich Dockyard by 2 July [O.S. 22 June] 1674:

| Item | Quantity | Notes | Total estimated weight | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Metric

kg | ||||||

| cwt | qr | lbs | |||||

| Nails | 98 Barrels | 601 | 0 | 14 | 30,539 | [44] | |

| Holland's duck canvas | 82 bales | 17,712 Yards (16.2 kilometres) | |||||

| Fine canvas | 5 bales | 1,292 yards (1,181 metres) | |||||

| Beef | 1 puncheon | Damaged | |||||

| Butter | 9 casks | 31 | 1 | 10 | 1,592 | ||

| Butter | 4 small casks | 0 | 0 | 280 | 127 | ||

| Pork | 32 casks | 105 | 1 | 20 | 5,356 | ||

| Rosin | 40 barrels | 153 | 0 | 16 | 7,780 | ||

| Pitch | 25 barrels | 90 | 2 | 21 | 4,607 | ||

| Tar | 77 barrels | 281 | 0 | 4 | 14,277 | ||

| Tallow | 8 casks | 47 | 2 | 13 | 2,419 | ||

| Grout | 25 Hogsheads | ||||||

| Grout & pea gravel mix | 13 hogsheads | ||||||

| Grout | 13 butts, pipes and puncheons | ||||||

| Rusk | 53 casks | ||||||

| Pea gravel | Twelve hogsheads | ||||||

| Oil | 4 Rundlets | ||||||

| Twine | 10 | 3 | 12 | 552 | |||

| Sail needles | 2400 | ||||||

| Herbs | 3 chests | Damaged | |||||

| Hogs' Bristles | 2 casks | 10 | 1 | 13 | 527 | ||

| Swines | 2 casks | ||||||

| Leather | 100 backs | ||||||

| Grindstones | 39 | ||||||

| Blacking | 255 barrels | ||||||

| Housing and marlings | Damaged, 1,345 small lines | 13 | 1 | 7 | 676 | ||

| Ram block with 4 brass Sheaves | 1 | Containing 4 Fathoms 11 Inches (7.59 metres) | |||||

| Ram block with lignum vities | 11 | Containing 21 fathoms 10 inches (38.66 metres) | |||||

| Block with ash sheaves | 63 | Containing 67 fathoms (122.5 metres) | |||||

| Anchors | 2 | 55 | 1 | 2 | 2,808 | ||

| Anchor | 1 | 6 | 0 | 24 | 316 | ||

| Grapnels | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 68 | ||

| Flour | 2 casks | 3 | 0 | 23 | 163 | ||

| Small cordage | 197 coils | 152 | 1 | 16 | 7,742 | [45] | |

| Sail | Size | Material | Condition | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Metric | ||||||

| Width

(cloths) |

Depth

(yards) |

Width

(metres)[lower-roman 4] |

Depth

(metres)[lower-roman 5] | ||||

| Bonnet | 29 | 1 ¾ | 53 | 1.5 | Duck canvas | ½ worn | [44] |

| Topsail | 21 | 14 | 38 | 12.75 | Duck canvas | ||

| Mizzen sail | 12 | 14 | 22 | 12.75 | Duck canvas | ||

| Spritsail | 22 | 5 ½ | 40 | 5 | ½ worn | ||

| Foresail | 29 | 8 ¼ | 53 | 7.5 | 20 yards damaged | ||

| Main canvas | 33 | 10 ¼ | 60 | 9.25 | |||

| Studding sail | 7 | 16 ¾ | 13 | 15.25 | Small canvas | ||

| Mainsail (piece) | 15 | 9 | 27 | 8.25 | ⅓ worn | ||

| Mizzen topsail | 13 | 7 ¾ | 24 | 7 | Small canvas | ||

| Boat sail | 5 ½ | 9 ½ | 10 | 8.75 | Duck canvas | ||

| Boat sail | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7.25 | Small canvas | ||

| Mizzen sail | 11 ½ | 17 | 21 | 15.5 | Duck canvas | ½ worn | [46] |

| Topsail | 15 | 8 | 27 | 7.25 | |||

| Topsail | 12 | 7 ¾ | 22 | 7 | Small canvas | ||

| Bonnet | 29 | 1 ¾ | 53 | 1.5 | Duck canvas | ||

| Boat sail | 2 ½ | 7 | 5 | 6.5 | Duck canvas | ||

| Course sail | 24 | 8 ½ | 44 | 7.75 | Duck canvas | ½ worn | |

| Staysail | 9 ½ | 10 | 17 | 9.25 | Duck canvas | New | |

| Bonnet | 29 | 2 | 53 | 1.75 | Duck canvas | New | |

| Topsail | 15 | 9 | 27 | 8.25 | Small cloth | ¾ worn | |

| Course sail (piece) | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7.25 | Duck canvas | ||

| Topsail | 13 | 7 ½ | 24 | 6.75 | ½ small canvas | ||

| Awning (piece) | 5 | 11 | 9 | 10 | Duck canvas | ½ worn | |

| Item | Size | Notes | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Metric | |||||

| Circumference

(Inches) |

Length

(Fathoms) |

Diameter

(mm) |

Length

(m) | |||

| Shroud hawser | 8 | 92 | 65 | 168 | [46] | |

| 8 | 66 | 65 | 121 | |||

| 8 | 93 | 65 | 170 | |||

| 7 ½ | 93 | 61 | 170 | |||

| 8 | 91 | 65 | 166 | |||

| Cable | 9 ¾ | 88 | 79 | 161 | ||

| 9 ½ | 87 | 77 | 159 | |||

| 11 | 87 | 89 | 159 | |||

| 11 | 89 | 89 | 163 | |||

| 10 ½ | 90 | 85 | 165 | |||

| 11 ½ | 86 | 93 | 157 | |||

| 8 ¾ | 87 | 71 | 159 | |||

| 8 ¾ | 90 | 71 | 165 | |||

| 8 ½ | 90 | 69 | 165 | |||

| 8 ½ | 93 | 69 | 170 | |||

| 8 ½ | 89 | 69 | 163 | |||

| 9 | 94 | 73 | 172 | |||

| 9 | 89 | 73 | 163 | |||

| 10 ½ | 9 | 85 | 16 | |||

| 7 ½ | 174 | 61 | 318 | |||

| 9 | 27 | 73 | 49 | |||

| 7 ½ | 86 | 61 | 157 | |||

| 8 | 87 | 65 | 159 | |||

| 12 | 86 | 97 | 157 | |||

| 11 | 94 | 89 | 172 | |||

| 13 | 90 | 105 | 165 | |||

| 13 | 90 | 105 | 165 | |||

| 15 | 87 | 121 | 159 | |||

| 17 | 86 | 137 | 157 | |||

| 15 ½ | 90 | 125 | 165 | |||

| 16 | 47 | 129 | 86 | |||

| 16 ½ | 88 | 133 | 161 | |||

| 20 | 89 | 162 | 163 | |||

| 20 | 89 | 162 | 163 | [45] | ||

| Rope with 4 strands | 5 ½ | 53 | 44 | 97 | ||

| Tacks | Two pieces | |||||

| Warp | 5 | 69 | 40 | 126 | ||

| Shot | 21 | 265 | 170 | 485 | ⅓ worn | |

| Tack | ||||||

| Tack | ½ worn | |||||

Fate of Wapen van Rotterdam

Wapen van Rotterdam was renamed HMS Arms of Rotterdam and was refitted as an unarmed hulk. In 1703 Arms of Rotterdam was broken down in Chatham.[47]

The Hollanders' Graves

The site where the bodies of those killed in the battle were buried is known as the Hollanders' Knowe, and the site is marked by a small granite cairn with a plaque that reads "The Hollanders' Graves". These are likely to be the first War graves recorded in Shetland.[16]

Notes

- "Wapen van Rotterdam" is Dutch for "Coat of arms of Rotterdam".

- Shetland supports only a small number of trees as of June 2014, although since the 1950s the number of trees has gradually increased[13]

- The value of the goods listed is the item's maximum sale value, not including advances that were offered to those buying all the goods in a single lot.

- Width given to the nearest metre

- Depth given to the nearest 25cm

References

- VOCsite 2019.

- Bruce 1914, p. 101.

- Three Decks 2019.

- London Gazette 27 March 1674, p. 2.

- Bruce 1914, p. 103.

- Edwardson.

- Pepys 1923, p. 30.

- London Gazette 2 March 1674, p. 2.

- DSL 2004.

- Bruce 1914, p. 102.

- Jack 1999, p. 349.

- BBC Guernsey 2008.

- Shetland.org 2014.

- Amsterdamsche Courant 10 April 1674.

- SASA.

- HEARD 2006.

- Graham 1979.

- Brand 1809, p. 767.

- Jack 1999, p. 359.

- Murdoch, Little & Forte 2005, p. 37.

- Three Decks – Cambridge 2019.

- Three Decks – Arthur Herbert 2019.

- Three Decks – Newcastle 2019.

- Three Decks – John Wetwang 2019.

- Three Decks – Taunton 2019.

- Three Decks – Richard Carter 2019.

- Three Decks – Dove 2019.

- Three Decks – Abraham Hyatt 2019.

- Pepys 1904, p. 247.

- Davenport 1929, p. 229.

- Pepys 1904, pp. 249–250.

- Pepys 1904, p. 249.

- Pepys 1904, p. 256.

- Pepys 1904, p. 261.

- Pepys 1904, p. 258.

- Shetland Museum SEA 7691.

- Three Decks – Wapen van Rotterdam 2019.

- Pepys 1904, p. 280.

- Pepys 1904, p. 281.

- Daniell 1904, pp. 291–292.

- Brouwer 2014, p. 49.

- A Sale of His Majesties Prize Goods by the Arms of Rotterdam, etc. 1674, p. 1.

- A Sale of His Majesties Prize Goods by the Arms of Rotterdam, etc. 1674, p. 2.

- Burgess 1674, p. 1.

- Burgess 1674, p. 3.

- Burgess 1674, p. 2.

- Three Decks – Arms of Rotterdam 2019.

Sources

- Brand, John (1809) [1701]. Pinkerton, John (ed.). A brief description of Orkney, Zetland, Pightland Firth, and Caithness, etc (In Pinkerton, John, Ed. A general collection of the best and most interesting voyages and travels). London. pp. 767. OCLC 1041608289. OL 13997155M.

Engliſh is the common language among them, yet many of the people ſpeak Norſe, or corrupt Daniſh, eſpecially ſuch as live in the more northern iſles; yea, ſo ordinary is it in ſome places, that it is the firſt language their children ſpeak. Several here alſo ſpeak good Dutch, even ſervants, though they have never been out of the country, becauſe of the many Dutch ſhips which do frequent their ports. And there are ſome who have ſomething of all theſe languages, Engliſh, Dutch and Norſe.

- Brouwer, Judith (2014). Levenstekens: Gekaapte brieven uit het Rampjaar 1672 [Signs of Life: Hijacked letters from the Disaster Year 1672]. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 49. ISBN 9789087044053.

- Bruce, R. Stuart (1914). Johnston, Alfred W.; Johnston, Amy (eds.). "Part III – Replies – Naval Engagement, Rønis Vo, Shetland" (PDF). Old-Lore Miscellany of Orkney Shetland Caithness and Sutherland. London: Viking Society for Northern Research. VII (Old-Lore Series Vol. VIII): 101–103 – via Viking Society Web Publications.

- Burgess, John (1674). An account of the p[r]u[vi]sions Rec[eive]d into his Ma[jesties] stores at Woolw[i]ch brought from on board the Armes of Rotterdam VIZ. ADM 106/295/327 (Letter). Woolwich, England. pp. 1–3.

- Daniell, Francis Henry Blackburne, ed. (1904) [1674]. Charles II: June 1674. Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles II, 1673-5. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 291–292. Retrieved 6 April 2019 – via British History Online.

Privy Seal to the Principal Commissioners of Prizes and the Lord High Treasurer for payment of 500l. to Capt. John Wetwang, commander of the Newcastle, out of the proceeds of sale of the goods out of the Arms of Amsterdam, bound for the East Indies and seized by him near the Shetland Isles and brought safe to the Thames, and, if the said goods do not produce the said sum, the Lord High Treasurer is to find out some other proper way for payment thereof, as a free gift. [S.P. Dom., Car. II. 359, p. 30.]

- Davenport, Frances Gardiner (1929). Jameson, J. Franklin (ed.). European treaties bearing on the history of the United States and its dependencies. 2. Robarts – University of Toronto. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. pp. 229–240. OCLC 717779114.

- Edwardson, John W. F. "Hollanders' Grave, and the Battle of Ronas Voe". roymullay.com. Eshaness, Shetland: Tangwick Haa Museum. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Graham, John J. (1979). "Introduction to The Shetland Dictionary". Shetland ForWirds. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Jack, William (1999) [1794]. Sinclair, Sir John (ed.). "Northmaven". The Statistical Account of Scotland Drawn up from the Communications of the Ministers of the Different Parishes. University of Edinburgh, University of Glasgow: Edinburgh: William Creech. 12 (27): 359. OCLC 1045293275. Retrieved 4 April 2019 – via The Statistical Accounts of Scotland online service.

- Murdoch, Steve; Little, Andrew; Forte, Angelo (2005). "Scottish Privateering, Swedish Neutrality and Prize Law in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672–1674". Forum Navale. 59: 37 – via academia.edu.

- Pepys, Samuel (1904) [1674]. Tanner, J. R. (ed.). "Admiralty Letters". Publications of the Navy Records Society. A Descriptive Catalogue of The Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. The Navy Record Society. 27 (2): 247–285. OCLC 848547357. OL 24226048M. Retrieved 26 March 2019 – via archive.org.

- Pepys, Samuel (1923) [1674]. Tanner, J. R. (ed.). "Admiralty Journal". Publications of the Navy Records Society. A Descriptive Catalogue of The Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. The Navy Record Society. 57 (4): 30. OCLC 827219323. OL 14003544M. Retrieved 26 March 2019 – via archive.org.

- A Sale of His Majesties Prize Goods by the Arms of Rotterdam, to be made at the East-India-House, on Thursday the 14th. of May 1674, at Eight of the Clock in the Morning; the particulars are, VIZ. sn. 1674. pp. 1–2.

- "Abraham Hyatt". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Arthur Herbert (1648–1716)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Barshot from the battle between V.O.C. Het Wapen van Rotterdam and the British squadron of HMS Newcastle, Crown, Buck, Cambridge. In Ronas Voe, Dec. 1674. ca. 1673. [Cast iron]. At: Shetland Museum and Archives. SEA 7691.

- "British 'Dove' (1672)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "British Fourth Rate ship of the line 'Newcastle' (1653)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "British Fourth Rate ship 'Taunton' (1654)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "British Third Rate ship of the line 'Arms of Rotterdam' (1674)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "British Third Rate ship of the line 'Cambridge' (1666)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "De VOCsite : gegevens VOC-schip Wapen Van Rotterdam (1666)" [The VOCsite: details of the VOC ship Wapen van Rotterdam (1666)]. www.vocsite.nl. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Dutch Merchantman east indiaman 'Wapen van Rotterdam' (1666)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Facts about Shetland". www.bbc.co.uk. 13 October 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Harwich, March 27" (PDF). The London Gazette (872). The Savoy: The Newcomb (published 30 March 1674). 27 March 1674. p. 2. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Hollanders Grave". www.heard.shetland.co.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Londenden 3 April" [London 3 April]. Engelandt. Amsterdamsche Courant (in Dutch) (15). Amsterdam: Mattheus Cousart (published 10 April 1674). 3 April 1674. p. 1. Retrieved 23 March 2019 – via Delpher.

- "Richard Carter (d.1692)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Shetland Cabbage/Kale: the oldest Scottish local vegetable variety?". SASA (Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture). Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Sir John Wetwang (d.1684)". threedecks.org. 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Sunderland, Febr. 22" (PDF). The London Gazette (864). The Savoy: The Newcomb (published 2 March 1674). 22 February 1674. p. 2. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Treeless? That's Changing..." Shetland.org. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Voe n". Dictionary of the Scots Language. Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd. 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

External links

- Dutch Prize Papers – Archive of papers aboard Wapen van Rotterdam when it was captured.

.jpg)