Battle of Mursa Major

The Battle of Mursa was fought on 28 September 351 between the eastern Roman armies led by the Emperor Constantius II and the western forces supporting the usurper Magnentius. It took place at Mursa, near the Via Militaris in the province of Pannonia (modern Osijek, Croatia). The battle, one of the bloodiest in Roman history, was a pyrrhic victory for Constantius.

| Battle of Mursa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman civil war of 350–353 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Empire | Roman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Magnentius | Constantius II | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~36,000[2] | 60,000[3]~80,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

23,760[lower-alpha 1][4]-24,000 Very large number of deaths[1] | 24,000[lower-alpha 2][5]-30,000[4][6] | ||||||

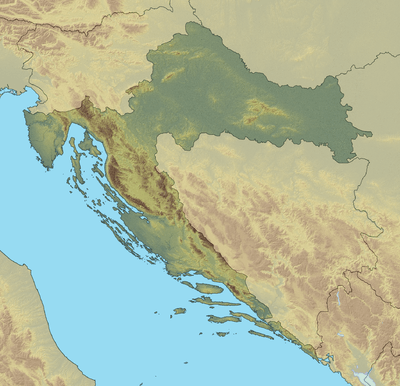

Location of the battle within modern Croatia | |||||||

Background

Following Constantine I's death in 337 the succession was far from clear.[7] Constantine II, Constantius II, and Constans were all Caesars overseeing particular regions of the empire,[7] although none of them were powerful enough to claim the title of Augustus.[8] Fueled by the belief that Constantine wished for his sons to rule in a tripartite after him, the military massacred Constantinian family members.[9] This massacre precipitated a redivisioning of the empire, by which Constantine took Gaul, Hispania, and Britain, while Constans acquired Italy, Africa, Dacia, and Illyricum, and Constantius inherited Asia, Egypt, and Syria.[10]

After attempting to impose his authority over Carthage and being blocked, Constantine II attacked his brother Constans in 340, but was ambushed and killed near Aquilia in northern Italy.[11] Constans took possession of the provinces of the west, and ruled for ten years over two-thirds of the Roman world.[11] In the meantime, Constantius was engaged in a difficult war against the Persians under Shapur II in the east.[11]

In 350, the mismanagement of Constans had alienated his generals and civilian officials and Magnentius had himself proclaimed Augustus of the west, resulting in the murder of Constans.[12] Magnentius quickly marched his army into Italy, appointing Fabius Titanius as praefectus urbi consolidating his influence over Rome.[12] By the time Magnentius' army arrived at the Julian passes, Vetranio, Constans' lieutenant in Illiyricum, had been declared Augustus by his troops.[12] Magnentius initially attempted a political dialogue with Constantius and Vetranio, but the rebellion by Nepotianus changed his intentions from joining the Constantian dynasty to supplanting it.[13] It was during this rebellion that Magnentius promoted his brother Decentius to Caesar.[12]

Constantius' reaction was limited.[13] Already involved in a war with the Sasanian Empire, he was in no position to deal with Magnentius or Vetranio.[13] Following Shapur's retreat from Nisibis, Constantius marched his army to Serdica meeting Vetranio with his army.[14] Instead of a battle, both Constantius and Vetranio appeared before the latter's army whereby Vetranio agreed to abdicate.[15] Constantius then advanced west with his reinforced army to encounter Magnentius.[3]

The battle

Magnentius marched an army of around 36,000 Gallic infantry, auxilia palatinae, Franks, and Saxons down the Via Militaris and besieged Mursa.[2][1] His siege was short-lived as Constantius' army, numbering nearly 80,000, arrived and Magnentius was forced to retreat.[2] Magnentius formed up his army on the open plain north-west of Mursa, near the Drava River,[2] with Constantius' army, which included armoured cavalry and mounted archers, directly across from them.[16]

Once his army was emplaced, Constantius sent his praetorian prefect, Flavius Philippus, with a peace settlement.[17] However, Flavius' true mission was to gather information on Magnentius' forces and sow dissent within the usurper's army.[18] After Flavius' speech to Magnentius' army nearly sparked a revolt, Magnentius had Flavius imprisoned and later executed.[18]

Meanwhile, Magnentius' set an ambush from an abandoned stadium, consisting of four Gallic phalanxes, which was discovered by Constantius' generals and eliminated.[16]

Constantius opened with battle with his cavalry charging both flanks of Magnentius' army.[16] Once Magnentius realized his right flank was nearly enveloped,[19] he fled the field.[16] Despite being abandoned by their Emperor, the Gallic infantry formed a double phalanx to coincide with the counter charge by Magnentius' cavalry.[16] Both Gallic and Saxon infantry refused to surrender, fighting on as berserkers and taking terrible losses.[16] Constantius' Armenian and mounted archers used a version of the Persian shower archery which caused disorder within Magnentius' forces.[20] This, combined with the armoured cavalry from the East, brought about the downfall of the usurper's army.[5]

By nightfall, the battle was all but finished, with two desperate groups of Magnentius' army fleeing the field.[20] One group fled towards the river while the other headed back to their encampment.[6] Both groups took heavy casualties.[6] Constantius, not even present at the battle, heard of his army's victory from the bishop of Mursa while visiting the tomb of a Christian martyr.[lower-alpha 3][4] Whereupon, Constantius informed those of the Christian community that his victory was due to God's aid.[21]

Aftermath

Following his victory at Mursa, Constantius chose not to pursue the fleeing Magnentius, instead spending the next ten months recruiting new troops and retaking towns occupied by Magnentius.[22] In the summer of 352, Constantius moved west into Italy, only to find that Magnentius had chosen not to defend the peninsula.[23] After waiting until September 352, he made Naeratius Ceralis praefectus urbi and moved his army to Milan for winter quarters.[23] It would not be until the summer of 353 that Constantius would move his army further west to confront Magnentius at the Battle of Mons Seleucus.[23]

Historiography of the battle

Numerous contemporary writers considered the loss of Roman lives at Mursa a disaster for the Roman Empire.[16] Crawford states the barbarian contingents took the lion's share of the casualties,[4] and yet the losses suffered at Mursa, according to Eutropius, could have won triumphs from foreign wars and brought peace.[24] Syvanne compares the losses at Mursa to the Roman defeats at Cannae and Adrianople.[6] Zosimus called the battle at Mursa a major disaster, with the army so weakened that it could not counter barbarian incursions,[25] while modern academics have labeled the battle a pyrrhic victory for Constantius.[6][4]

Notes

References

- Angelov 2018, p. 1059.

- Syvanne 2015, p. 324.

- Crawford 2016, p. 77.

- Crawford 2016, p. 80.

- Potter 2004, p. 473.

- Syvanne 2015, p. 326.

- Crawford 2016, p. 29-30.

- Leadbetter 1998, p. 80.

- Crawford 2016, p. 31.

- Crawford 2016, p. 35.

- Crawford 2016, p. 64.

- Barnes 1993, p. 101.

- Crawford 2016, p. 74.

- Crawford 2016, p. 75.

- Crawford 2016, p. 76.

- Syvanne 2015, p. 325.

- Crawford 2016, p. 78.

- Syvanne 2015, p. 322.

- Tucker 2010, p. 158.

- Syvanne 2015, p. 325-326.

- Potter 2004, p. 474.

- Crawford 2016, p. 80-81.

- Crawford 2016, p. 81.

- Lee 2007, p. 73.

- Potter 2004, p. 473-474.

Sources

- Angelov, Alexander (2018). "Mursa and Battles of Mursa". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1047. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnes, Timothy David (1993). Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-05067-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crawford, Peter (2016). Constantius II: Usurpers, Eunuchs, and the Antichrist. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978 1 78340 055 3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leadbetter, Bill (1998). "The illegitimacy of Constantine and the birth of the tetrarchy". In Lieu, Samuel N. C.; Montserrat, Dominic (eds.). Constantine: History, Historiography and Legend. Routledge. p. 74-85. ISBN 0-415-10747-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, A.D. (2007). War in Late Antiquity. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22925-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potter, David S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10058-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). The Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Volume One. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Syvanne, Ilkka (2015). Military History of Late Rome, 284-361. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978 1 84884 855 9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)