Battle of Kostiuchnówka

The Battle of Kostiuchnówka was a World War I battle that took place July 4–6, 1916, near the village of Kostiuchnówka (Kostyukhnivka) and the Styr River in the Volhynia region of modern Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. It was a major clash between the Russian Army and the Polish Legions (part of the Austro-Hungarian Army) during the opening phase of the Brusilov Offensive.

| Battle of Kostiuchnówka | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Brusilov Offensive during the First World War | |||||||

Polish Legionnaires at Kostiuchnówka | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(Polish Legions) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Józef Piłsudski | Alexey Kaledin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,500[1]-7,300[2] | 13,000[1] or more[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000[3] | Unknown | ||||||

Polish forces, numbering 5,500–7,300, faced Russian forces numbering over half of the 46th Corps of 26,000. The Polish forces were eventually forced to retreat, but delayed the Russians long enough for the other Austro-Hungarian units in the area to retreat in an organized manner. Polish casualties were approximately 2,000 fatalities and wounded. The battle is considered one of the largest and most vicious of those involving the Polish Legions in World War I.[3][4]

Background

In World War I, the partitioners of Poland fought each other, with the German Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire aligned against the Russian Empire. The Polish Legions were created in Austro-Hungary in order to exploit these divisions, serving as one of his primary tools for restoring Polish independence.[5]

The Polish Legions first arrived in the vicinity of Kostiuchnówka during the advance of the Central Powers in the summer and autumn of 1915, taking Kostiuchnówka on September 27, 1915.[6] That autumn they experienced heavy fighting, with each side trying to take control of the region; a less known battle of Kostiuchnówka took place from November 3 to 10; the Russians managed to make some advances, taking the Polish Hill, but were expelled by the Polish forces on September 10.[4] Polish forces held Kostiuchnówka, and due to their successes in defending their positions, several landmarks in the Kostiuchnówka region became known as "Polish" (called such by Polish as well as by allied German-speaking troops): a key hill overlooking the area became the Polish Hill (Polish: Polska Góra), a nearby forest – the Polish Forest (Polski Lasek), a nearby bridge over the Garbach – the Polish Bridge (Polski Mostek), and the key fortified trench line – Piłsudski's Redoubt (Reduta Piłsudskiego).[6] Polish soldiers built several large wooden camps; the larger of which was known as Legionowo (where the Polish HQ was located).[4] During the preceding late autumn, winter and spring there were no major moves by either side, but this changed drastically with the launching of the Brusilov Offensive in June 1916.[6] It would be a major Russian victory, and the greatest of Austro-Hungarian defeats.[7]

Opposing forces

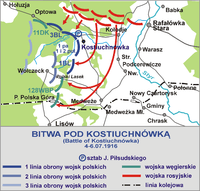

Facing the major Russian offensive, the II Brigade of the Polish Legions was deployed out of Kostiuchnówka, at Gruziatyn and Hołzula.[2] The I Brigade held the lines advancing down the Polish Hill, Kostiuchnówka village; the III Brigade, positioned to its left, held the lines near the Optowa village; the Piłsudski's Redoubt was the most advanced Polish position, just about 50 metres (164 ft) facing head on the most advanced Russian redoubt, called the "Eagle's Nest".[2] Further down the Polish Hill the Hungarian 128th Honvédség Brigade took positions opposite the Polish right flank, the Hungarian 11th Cavalry Division opposite the left flank.[2] Two Polish fall-back lines were drawn beyond the first line of defense: one drawn through the Polish Forest and the Engineer's Forest, and the second one through the villages of Nowe Kukle, Nowy Jastków, the camp of Legionowo and Nowa Rarańcza. The Polish Legions at Kostiuchnówka numbered from 5,500[1] to 7,300 (6,500 infantry and 800 cavalry), with forty-nine machine guns, fifteen mortars and twenty-six artillery units.[2] The Russian forces, composed of the most part of the 46th Corps (primarily the 110th and 77nd Infantry Division), numbered 23,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and were backed up by a larger artillery force consisting of 120 units.[2]

The battle

Starting on June 6, a major Russian push was directed against the 40 km line between Kołki and Kostiuchnówka,[4] with the aim of taking the position and then advancing towards Kovel.[2] With Polish legionnaires staying put and holding the ground, more Russian reinforcements were thrown in, while the battle of Kostiuchnówka had become one of the major struggles in the area during World War I.[2] Polish forces launched a counterattack, pushing back the Russians – who had not expected such a bold move – on the night of June 8 and 9.[2]

The major Russian push came on July 4, after a major artillery pre-emptive assault.[8] The advancing Russian infantry, numbering around 10,000, faced about 1,000 Polish troops in the front lines (the rest were held in reserve), but the Russians were stopped by heavy machine gun fire and forced to retreat.[8] The Hungarian forces at Polish Hill were pushed back, however, and the Russians advancing on the Poles' right flank, threatened to take the high ground in the area.[9] A counterattack by the Poles was not successful; as the Hungarian units were retreating, the Polish forces sustained very heavy losses and had to fall back either to the remaining part of the first defense line or, in the area of Polish Hill, to the second line.[9] Another Polish counterattack, launched during the night of July 4/5, was also beaten back.[9] Throughout the day, the Russian offensive managed to push the Polish forces further back; although the Poles managed to temporarily retake Polish Hill, a lack of support from the Hungarian forces once again tipped the battle towards the Russians, and even German reinforcements – deployed after Piłsudski sent a report to the army's headquarters about the possibility of a Russian breakthrough – failed to turn the tide away.[10] Eventually, on July 6, the Russian offensive forced the Central Powers' armies to retreat along the entire frontline; Polish forces were among the last to retreat,[10] having sustained approximately 2,000 casualties during the battle.[3]

Aftermath

Brusilov's offensive was stopped only in August 1916, with reinforcements from the Western Front. Despite being forced to retreat, the performance of the Polish forces impressed Austro-Hungarian and German commanders, and contributed to their decision to recreate some form of Polish statehood in order to boost the recruitment of Polish troops.[3] Their limited concessions, however, did not satisfy Piłsudski; in the aftermath of the Oath Crisis he was arrested and the Legions disbanded.[3]

The presence of Piłsudski, who would later become the dictator of Poland, during the battle, became a subject of several patriotic Polish paintings, including one by Leopold Gottlieb, then also a soldier of the Legions,[11] as well as of another painting by Stefan Garwatowski.[12] Wincenty Wodzinowski created a series of drawings and sketches on the dead and wounded from the battle.[12] During the Second Polish Republic, several monuments and a mound were raised nearby to commemorate the battle. A 16 m mound with a stone obelisk and a museum with two additional obelisks were raised during the years 1928–1933;[13] a military cemetery was also built.[10] They fell into disrepair during the rule of the Soviet Union (which often purposefully tried to erase traces of Polish history – the mound was for example lowered by 10 m). In recent years restoration work has taken place through various Polish-Ukrainian projects, with notable projects carried out by Polish boy scouts.[10][13]

The battle is considered one of the largest and most vicious of those involving the Polish Legions in World War I.[4] Piłsudski in his order of July 11, 1916 wrote that "the heaviest of our current fights took place in the recent days."[3]

Notes

- Polish Ministry of Defence

- Bitwa..., p.6

- Bitwa..., p.12

- Rakowski, p.109-111

- Urbankowski, p. 155-165

- Bitwa..., p.5

- Graydon A. Tunstall, “Austria-Hungary and the Brusilov Offensive of 1916,” The Historian 70.1 (Spring 2008): 52.

- Bitwa..., p.7

- Bitwa..., p.8

- Bitwa..., p.10

- "Józef Pilsudski Institute of America - Gallery". Pilsudski.org. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- "Rosjanie – Polacy, czterech na jednego (galeria zdjęć)" (in Polish). rp.pl. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- Sobczak

References

- (in Polish) Bitwa pod Kostiuchnówką, Zwycięstwa Oręża Polskiego Nr 16. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Various authors and editors, primarily Tomasz Matuszak. June 17, 2006

- (in Polish) 90. rocznica bitwy pod Kostiuchnówką 90th anniversary of the battle on the pages of Polish Ministry of Defence

- (in Polish) Grzegorz Rąkowski, Wołyń: przewodnik krajoznawczo-historyczny po Ukrainie Zachodniej, Oficyna Wydawnicza "Rewasz", 2005, ISBN 83-89188-32-5, Google Print, p.109

- (in Polish) Jerzy Sobczak, Kopce na ziemiach kresowych, Magazyn Wileński 2003/3

- (in Polish) Bohdan Urbankowski – Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg, Wydawnictwo ALFA, Warsaw, 1997, ISBN 83-7001-914-5, p. 155-165 (rozdział IV Legiony, podrozdział I 'Dzieje idei')

Further reading

- (in Polish) Stanisław Czerep, Kostiuchnówka 1916, Bellona, Warszawa, 1994, ISBN 83-11-08297-9

- (in Polish) Szlakiem Józefa Piłsudskiego 1914–1939, Warszawa, nakł. Spółki Wydawniczej "Ra", 1939 (reported to have several photos from the battle of Kostiuchnówka)

- (in Polish) Michał Klimecki, Pod rozkazami Piłsudskiego : bitwa pod Kostiuchnówką 4–6 lipca 1916 r., z serii "Bitwy Polskie", Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy Związków Zawodowych, 1990, ISBN 83-202-0932-3

- (in Polish) Włodzimierz Kozłowski, Artyleria polskich formacji wojskowych podczas I wojny światowej, Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź, 1993, ISBN 83-7016-697-0

External links

- Map of the battle

- (in Polish) Uroczystości w Kostiuchnówce na Ukrainie

- (in Polish) Dariusz Nowiński, Kostiuchnówka 1916. Największa polska bitwa I wojny światowej, Komendant, Naczelnik, Marszałek. Józef Piłsudski i jego czasy