Battle of Handschuhsheim

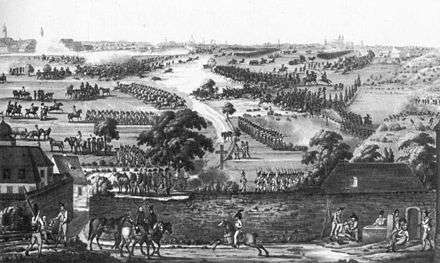

The Battle of Handschuhsheim or Battle of Heidelberg (24 September 1795) saw an 8,000-man force from Habsburg Austria under Peter Vitus von Quosdanovich face 12,000 men from the Republican French army led by Georges Joseph Dufour. Thanks to a devastating cavalry charge, the Austrians routed the French with disproportionate losses. The fight occurred during the War of the First Coalition, part of the French Revolutionary Wars. Handschuhsheim is now a district of Heidelberg, but it was a village north of the city in 1795.

In early 1795 many of France's enemies made peace, leaving only Austria and Great Britain in opposition. In September, the French government ordered the armies of Jean-Charles Pichegru and Jean-Baptiste Jourdan to attack the Austrian armies on the Rhine River. The French scored early successes, capturing two key cities and crossing the river in force. Pichegru sent two divisions to seize the Austrian supply base at Heidelberg, but his troops were bloodily repulsed at Handshuhsheim. Afterward, the Austrian commander François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt turned on Jourdan's army, driving it back across the Rhine. The Austrians later won the battles of Mainz, Pfeddersheim and Mannheim, forcing the French armies back onto the west bank of the Rhine.

Background

On 19 January 1795, the French army of General of Division Jean-Charles Pichegru seized Amsterdam, extinguished the Dutch Republic, and set up the satellite Batavian Republic. The armies of the First French Republic stood victorious on the west bank of the Rhine. The Kingdom of Prussia, intent on joining the Russian Empire in carving up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, desired to exit from the First Coalition. Not wishing to be swamped by thousands of unemployed soldiers at the peace, the French Directory drove a very hard bargain. Nevertheless, Prussia, the Electorate of Saxony, Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Electorate of Hanover, and Kingdom of Spain chose to make peace with France. Only the United Kingdom and Habsburg Austria continued the struggle. The Directory relaxed price controls and soon the cost of food and clothing shot up. Bread riots broke out in Paris during April and May, and mobs invaded the National Convention. The Directory struck back. On 22 May 1795, Pichegru led troops in putting down a revolt in the Faubourg Sainte-Antoine; nine of the arrested ringleaders killed themselves or were executed.[1]

On 4 November 1794, General of Division Jean Baptiste Kléber with a corps of 35,605 Frenchmen captured Maastricht from its Austro-Dutch garrison of approximately 8,000 troops. The French forces included the divisions of Generals of Division Jean Baptiste Bernadotte (9,215), Joseph Léonard Richard (9,961), Guillaume Philibert Duhesme (7,663), and Louis Friant (8,769). In exchange for turning over the fortress with 344 artillery pieces and 31 colors, Prince Frederick of Hesse-Kassel and his soldiers were allowed to march away. French casualties in the siege numbered 300 while their enemies lost 500.[2] Freed for more operations, Kléber moved against Mainz. Lacking the numbers or the heavy guns to place the fortress under regular siege, the French general contented himself with blockading the city starting on 14 December 1794. Another deterrent to more aggressive French action was the presence of an Austrian army under Feldzeugmeister François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt and General der Kavallerie Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser on the east bank of the Rhine.[3] Clerfayt was soon promoted Feldmarschall on 22 April 1795.[4] The futile blockade of the fortress of Mainz on the west bank dragged on through the summer.[3]

The Directory instructed Pichegru with the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle and General of Division Jean-Baptiste Jourdan with the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse to mount two converging thrusts across the Rhine. The plan called for Pichegru to attack anywhere between Mannheim and Strasbourg while Jourdan crossed farther to the north near Düsseldorf.[5] Jourdan struck across the Rhine in early September and advanced toward the County of Nassau-Usingen.[3] Instead of crossing the Rhine farther south, Pichegru moved north until he was opposite enemy-held Mannheim.[6]

On 20 September 1795 Pichegru and 30,000 soldiers secured Mannheim without a shot being fired. After negotiations, Baron von Belderbusch and his 9,200-man garrison from the Electorate of Bavaria handed the city and 471 artillery pieces over to the French and marched away. The Austrians were furious, but powerless to intervene. The loss of Mannheim forced the Austrians to retreat to the north behind the Main River. The next day, a second Bavarian garrison at Düsseldorf surrendered to General of Division François Joseph Lefebvre and 12,600 French soldiers. Count Hompesch and his 2,000 soldiers were allowed to leave by promising not to fight the French for one year, but 168 fortress guns fell into French hands.[7]

Battle

With the capture of Mannheim, Pichegru had a golden opportunity to seize Clerfayt's main supply base at Heidelberg. Clerfayt's army was too far north to save the supply base, while Wurmser's army was still in the process of assembling. However, Pichegru fumbled by sending only two divisions to seize Heidelberg. Worse, the French forces were split by the Neckar River. The 6th Division of General of Division Jean-Jacques Ambert moved on the south bank of the river while the 7th Division of General of Division Georges Joseph Dufour advanced on the north bank.[6] Dufour was in overall command of the 12,000 French soldiers. Generals of Brigade Louis Joseph Cavrois and Pierre Vidalot du Sirat led the brigades in Dufour's division while General of Brigade Louis-Nicolas Davout and Adjutant-General Bertrand headed brigades in Ambert's division. Other than the division and brigade commanders, the French order of battle is not known exactly.[7]

Feldmarschall-Leutnant Peter Vitus von Quosdanovich defended Heidelberg with approximately 8,000 Austrian troops.[7] He posted the brigade of General-major Adam Bajalics von Bajahaza at Handschuhsheim on the north bank, the brigade of General-major Michael von Fröhlich on the south bank at Kirchheim, and the brigade of General-major Andreas Karaczay farther south at Wiesloch.[8] On 23 September, the French were able to press back their adversaries, but Quosdanovich rapidly concentrated the bulk of his forces on the north bank against Dufour's isolated division.[6][note 1]

Quosdanovich's foot soldiers were made up of two battalions each of the Archduke Charles Infantry Regiment Nr. 3, Kaunitz Infantry Regiment Nr. 20, Wartensleben Infantry Regiment Nr. 28, and Slavonier Grenz Infantry Regiment and one battalion each of the Lattermann Infantry Regiment Nr. 45 and Warasdiner Grenz Infantry Regiment. The Austrian cavalry was placed in the hands of Johann von Klenau[7] recently promoted Oberst (colonel) on 8 September.[9] The mounted arm consisted of six squadrons each of the Hohenzollern Cuirassier Regiment Nr. 4 and Szekler Hussar Regiment Nr. 44, four squadrons of the Allemand Dragoon Regiment, an Émigré unit, and three squadrons of the Kaiser Dragoon Regiment Nr. 3.[7]

As Dufour's troops moved through open country, they were charged by Klenau's horsemen. The Austrians first routed six squadrons of French chasseurs à cheval then turned against the foot soldiers. Dufour's division was cut to pieces.[7] Numbers of French soldiers found and crossed a ford to the south bank where they joined Ambert's men.[6] Dufour was wounded and captured, du Sirat was wounded, and at least 1,000 Frenchmen became casualties. The Austrians rounded up 500 prisoners and captured eight guns and nine artillery caissons. Austrian losses were much lower, 35 killed, 150 wounded, and two missing.[7][note 2]

Aftermath

Jourdan wished to concentrate the two French armies near Mannheim, but Pichegru refused to cooperate.[5] While the two French commanders waited on fresh instructions from Paris, Jourdan surrounded Mainz and Pichegru used Mannheim as a base. Soon, Wurmser became strong enough to pin down Pichegru, allowing Clerfayt to launch an offensive against Jourdan. Moving around Jourdan's left flank, the Austrians placed the French in a difficult spot. After a repulse at the Battle of Höchst on 11 and 12 October 1795, Jourdan's army began retreating to the north. By the 20th, the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse had recrossed to the west bank of the Rhine.[3]

Wurmser with 17,000 troops defeated Pichegru with 12,000 in the Battle of Mannheim on 18 October 1795. For the loss of 709 killed, wounded, and missing, the Austrians inflicted 1,500 casualties on the French. In addition, Wurmser's army captured 500 soldiers, three guns, and one color. The Austrians overran the French camp outside Mannheim and placed the city under siege.[10] On 29 October, Clerfayt mounted a surprise attack on the French lines near Mainz.[3] In the Battle of Mainz, 27,000 Austrians defeated 33,000 French under General of Division François Ignace Schaal. The Austrians suffered 1,600 casualties while the French lost 4,800 killed, wounded, and missing, plus 138 guns and 494 wagons.[10] Clerfayt then turned south to deal with the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle. Winning the Battle of Pfeddersheim on 10 November and other actions, the Austrians relentlessly drove Pichegru's army south down the west bank of the Rhine until Mannheim was completely isolated.[5] On 22 November the Siege of Mannheim ended when the 10,000-man French garrison surrendered to Wurmser's 25,000 Austrians.[10]

Pichegru's fidelity by this time was highly dubious. He was disenchanted with the French Revolution and hoped for a popular monarchy. Worse, since 1794 he had been in contact with Émigré leader Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé's agents. The Directory doubted his loyalty but was unable to act because Pichegru was a national hero. After the Coup of 18 Fructidor in 1797, Pichegru's treasonous correspondence was made public and he was exiled. However, he escaped and fled to Great Britain. In 1803 he returned to France with royalist conspirator Georges Cadoudal, was caught by Napoleon's secret police, and died in suspicious circumstances in a prison cell.[5]

Notes

- Footnotes

- Rickard stated that the battle was fought on 25 November, while Smith and Boycott-Brown gave the 24th.

- Smith stated that the French lost 1,000 killed without giving the numbers of wounded.

- Citations

- Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1975). The Age of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: MJF Books. pp. 84–85. ISBN 1-56731-022-2.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. pp. 94–95. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rickard, J. "Siege of Mainz, 14 December 1794-29 October 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Smith, Digby; Kudrna, Leopold. "Austrian Generals of 1792-1815: Clerfayt de Croix". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 21 January 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rickard, J. "Jean-Charles Pichegru, 1761-1804". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Rickard, J. "Combat of Heidelberg, 23-25 September 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Smith (1998), pp. 104-105

- Boycott-Brown, Martin. "Quosdanovich, Peter Vitus von". historydata.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Smith, Digby; Kudrna, Leopold. "Austrian Generals of 1792-1815: Klenau und Janowitz, Johann Joseph Cajetan Graf von". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 22 January 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith (1998), p. 107-108

References

- Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1975). The Age of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: MJF Books. ISBN 1-56731-022-2.

- Boycott-Brown, Martin. "Quosdanovich, Peter Vitus von". historydata.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Rickard, J. "Combat of Heidelberg, 23-25 September 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Rickard, J. "Jean-Charles Pichegru, 1761-1804". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Rickard, J. "Siege of Mainz, 14 December 1794-29 October 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.