Bambooworking

Bambooworking is the activity or skill of making items from bamboo, and includes architecture, carpentry, furniture and cabinetry, carving, joinery, and weaving. Its historical roots in Asia span cultures, civilizations, and millennia.

History

Bamboo has hundred of species and grows in large swathes across parts of East, South, and Southeast Asia. Along with wood, stone, sand, clay and animal parts, bamboo was one of the first materials worked by early humans. The development of civilization was closely tied to the development of increasingly greater degrees of skill in working these materials. Just like woodworking, it came to be used for bamboo construction, bamboo textiles, bamboo and wooden slips, bamboo musical instruments, bamboo weaving, and many other areas.

China

Bamboo's long life makes it a Chinese symbol of uprightness. The rarity of its blossoming has led to the flowers' being regarded as a sign of impending famine. This may be due to rats feeding upon the profusion of flowers, then multiplying and destroying a large part of the local food supply. In Chinese culture, the bamboo, plum blossom, orchid, and chrysanthemum (often known as méi lán zhú jú 梅兰竹菊) are collectively referred to as the Four Gentlemen. These four plants also represent the four seasons and, in Confucian ideology, four aspects of the junzi ("prince" or "noble one"). The pine (sōng 松), the bamboo (zhú 竹), and the plum blossom (méi 梅) are also admired for their perseverance under harsh conditions, and are together known as the "Three Friends of Winter" (岁寒三友 suìhán sānyǒu) in Chinese culture. Bamboo, one of the "Four Gentlemen" (bamboo, orchid, plum blossom and chrysanthemum), plays such an important role in traditional Chinese culture that it is even regarded as a behavior model of the gentleman. As bamboo has features such as uprightness, tenacity, and hollow heart, people endow bamboo with integrity, elegance, and plainness, though it is not physically strong. Countless poems praising bamboo written by ancient Chinese poets are actually metaphorically about people who exhibited these characteristics. According to laws, the Tang dynasty Chinese poet, Bai Juyi (772–846), thought that to be a gentleman, a man does not need to be physically strong, but he must be mentally strong, upright, and perseverant. Just as a bamboo is hollow-hearted, he should open his heart to accept anything of benefit and never have arrogance or prejudice.

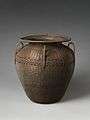

The use of bamboo in Neolithic China is well established as the Chinese were among the first civilizations to employ the use of bamboo.[1][2] The cultivation and application of bamboo has played an important in the development of Chinese civilization from prehistoric times to the present.[3][4][5] From prehistoric times to the present, bamboo has been used extensively in one form or another as the use of bamboo affected the everyday life of Chinese civilization. Chinese poets extolled this plant and Chinese painters cherished the plant's beauty and grace through paintings across various Chinese dynasties.[6] Archaeological ruins signifying the Chinese use of bamboo for vessels and containers, woven baskets to mats dating back to the Neolithic era were unearthed from Qianshanyang, Zhejiang.[7] Around 6000 BC, bamboo motifs were used to decorate the neolithic pottery of the Yangshao culture and bamboo baskets dating back to 2000 BC have been discovered in addition to bamboo slips that were used as a writing surface dating from the Warring States period (475 - 221 BC).[8] Bamboo during prehistoric China was used for a variety of purposes such as rafts, fans, cutting knives, arrowheads, chisels, needles, saw blades, cooking utensils, loomweights and writing tools.[9][10][11]

There are about 300 species of bamboo found in China, the greatest number of any country covering 12,350 square miles.[12] The Chinese appreciated bamboo as the material was strong and pliant. Bamboo leaves were often depicted in Chinese art. In addition, the use of bamboo was employed to make a wide variety of daily items such as containers, chopsticks, hats, trays, mats, baskets, umbrellas, rafts, building materials, fences, drilling materials, weapons, medicine, musical instruments, pipelines and raincoats.[13][14] Thin strips of bamboo were woven together and the stalks were heated and bent to make chairs, beds, drawers, tables, and folding screens.[15][16]

Japan

.jpg)

More than six hundred species of bamboo grow in Japan, including the Phyllostachys bambusoides variety, which can grow to a height of 15–22 m and a diameter of 10–15 cm. Although defined as a subfamily of grasses, bamboo is characterized by its woody culm and a root system that can form either aggressive runners or thick, slowly spreading clusters.[17]

Bamboo is a common theme in Japanese literature and a favoured subject of painters. Along with the evergreen pine and plum, which is the first flower of spring, bamboo is a part of the traditional Three Friends of Winter. The three are a symbol of steadfastness, perseverance, and resilience. Japanese artists have often represented bamboo enduring inclement weather, such as rain or snow, reflecting its reputation for being flexible but unbreakable, and its association with steadfastness and loyalty.[17]

Bamboowork (竹細工, takezaiku) is a traditional Japanese craft with a range of fine and decorative arts, and has been used for traditional architecture as well as for utilitarian objects such as fans, tea scoops, and flower baskets. Objects were used in the 8th century for Buddhist rituals and one of the oldest surviving baskets is housed in the Shōsō-in in Nara. The 16th century tea master Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) advocated for a simple, austere tea style (wabi-cha) with natural or seemingly artless utensils. These tea utensils established a Japanese bamboo art distinct from the imported Chinese style.[17] Examples of tea utensils made out of bamboo are lid rests (futaoki 蓋置), flower vessels (take-hanaire 花入), basketry flower vessels (kago-hanaire) which are usually reserved for use in the warm season, kettle mats (takekamashiki 釜敷), ash receptacle bamboo tubes (haifuki 灰吹), ladles (hishaku 柄杓), tea scoops (chashaku 茶杓), and whisks (chasen 茶筅). Tea masters have traditionally carved their own scoops, providing them with a bamboo storage tube (tsutsu), as well as a poetic name (mei 銘) that will often be inscribed on the storage tube. Recognition of bamboo craftsmanship as a traditional Japanese decorative art began in the end of the 19th century, and became accepted as an art form.[17]

Apart from carving bamboo, another important area is bamboo weaving.

Supplemental usage of bamboo in architecture can include scaffolding, windows, walls, fences, and water pipes such as shishi-odoshi. Items for catching, transporting, and preparing food can include cages, baskets, cooking vessels, rollers, and chopsticks. Items for personal hygiene carved out of bamboo are traditional combs, earpicks, and toothpicks. Personal Items such as hats and shoes out of thin strips were made, as well as parasols and fans. Bamboo was also crafted into weapons such as the yumi and arrows, spears, and for martial arts such as the shinai. Bamboo textiles could be won to be used for ropes and even woven as a fabric. A whole range of musical wind instruments are also crafted out of bamboo, such as the hotchiku, kagurabue, komabue, minteki, nohkan, ryūteki, shakuhachi, shinobue, and yokobue.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry designated it a traditional craft with the following groups:

- Edo Wadanpo (Tokyo)

- Suruga Bamboo Chikusa (Shizuoka)

- Osaka Kanemonen (Osaka)

- Takayama Chara (Nara)

- Katsuyama Bamboo Works (Okayama Prefecture)

- Beppu Bamboo Works (Oita Prefecture)[18][19]

- Miyakonojo big bow (Miyazaki)

Bamboo tea utensils such as the whisk, fan, and scoop

Bamboo tea utensils such as the whisk, fan, and scoop Flower vase Onkyoku, by Sen no Rikyū, 16th century

Flower vase Onkyoku, by Sen no Rikyū, 16th century

_(15516789331).jpg)

Large flower basket, bamboo (madake) with rattan accents, 2nd half of the 19th century, by Hayakawa Shōkōsai I

Large flower basket, bamboo (madake) with rattan accents, 2nd half of the 19th century, by Hayakawa Shōkōsai I

References

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108.

- Qian, Gonglin (2000). Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics. Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1592650200.

- Lu, Yongxiang (2014). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. 3. Springer (published October 20, 2014). p. 469. ISBN 978-3662441626.

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108.

- Needham, Joseph (1981). Science in Traditional China: A Comparative Perspective. The Chinese University Press. pp. 92, 266.

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108.

- Qian, Gonglin (2000). Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics. Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1592650200.

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108.

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108.

- Major, John S.; Cook, Constance A. (2016). Ancient China: A History. Routledge (published September 16, 2016). p. 39. ISBN 978-0765616005.

- Qian, Gonglin (2000). Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics. Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1592650200.

- Perkins, Dorothy (1998). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1579581107.

- Cumo, Christopher Martin (2013). Encyclopedia of Cultivated Plants: From Acacia to Zinnia. ABC-CLIO. p. 80. ISBN 978-1598847741.

- Moore, Marvelene C.; Ewell, Philip. Kaleidoscope of Cultures: A Celebration of Multicultural Research and Practice. R&L Education. p. 59. ISBN 978-1607093015.

- Perkins, Dorothy (1998). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-1579581107.

- Moore, Marvelene C.; Ewell, Philip. Kaleidoscope of Cultures: A Celebration of Multicultural Research and Practice. R&L Education. p. 59. ISBN 978-1607093015.

- Bincsik, Monika; Moroyama, Masanori (2017). Japanese Bamboo Art: The Abbey Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48. ISBN 9781588396143.

- http://www.city.beppu.oita.jp/06sisetu/takezaiku/english/takezaiku.html

- http://www.pref.oita.jp/site/280/

External links

![]()