Baltistan

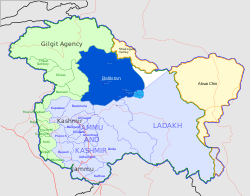

Baltistan (Urdu: بلتستان, Balti: སྦལ་ཏི་སྟཱན), also known as Baltiyul or Little Tibet (Balti: སྦལ་ཏི་ཡུལ་།), is a mountainous region in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan-administered Kashmir. It is located near the Karakoram mountains just south of K2 (the world's second-highest mountain), and borders Gilgit to the west, China's Xinjiang to the north, Ladakh to the southeast, and the Kashmir Valley to the southwest.[1][2] Its average altitude is over 3,350 metres (10,990 ft).

A map of the Baltistan region, in Gilgit-Baltistan and Ladakh | |

| Coordinates: 35°18′N 75°37′E | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Region | Gilgit-Baltistan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 72,000 km2 (28,000 sq mi) |

| Languages | |

Prior to 1947, Baltistan was part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, having been conquered by Raja Gulab Singh's armies in 1840.[3] Baltistan and Ladakh were administered jointly under one wazarat (district) of the state. Baltistan retained its identity in this set-up as the Skardu tehsil, with Kargil and Leh being the other two tehsils of the district.[4] After the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India, Gilgit Scouts overthrew the Maharaja's governor in Gilgit and captured Baltistan. The Gilgit Agency and Baltistan have been governed by Pakistan ever since.[5] The Kashmir Valley and the Kargil and Leh tehsils were retained by India. A small portion of Baltistan, including the village of Turtuk in the Nubra Valley, was incorporated into Ladakh after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[6][7]

The region is inhabited primarily by Balti people of Tibetan descent. The vast majority of the population follows Islam. Baltistan is strategically significant to Pakistan and India; the Kargil and Siachen Wars were fought there.

Geography

The 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica characterises Baltistan as the western extremity of Tibet,[8] whose natural limits are the Indus river from its abrupt southward bend around the map point 35.86°N 74.72°E and the mountains to the north and west. These features separate a comparatively peaceful Tibetan population from the fiercer Indo-Aryan tribes to the west. Muslim writers around the 16th century speak of Baltistan as the "Little Tibet", and of Ladakh as the "Great Tibet", emphasising their ethnological similarity.[8] According to Ahmad Hassan Dani, Baltistan spreads upwards from the Indus river and is separated from Ladakh by the Siachen glacier.[9] It includes the Indus valley and the lower valley of the Shyok river.[10]

Baltistan is a rocky mass of lofty mountains, the prevailing formation being gneiss. In the north is the Baltoro Glacier, the largest out of the arctic regions, 56 kilometres (35 mi) long, contained between two ridges whose highest peaks to the south are 7,600 m (25,000 ft) and to the north 8,615 m (28,265 ft).[8]

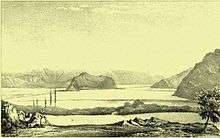

The Indus river runs in a narrow gorge, widening after receiving the Shyok river at 35.23°N 75.92°E. It then forms a 32-kilometre (20 mi) crescent-shaped plain varying between 2 and 8 kilometres (1 and 5 mi) wide.[11] The main inhabitable valleys of Kharmang Khaplu, Skardu and Roundu are along the routes of these rivers.

Valleys and districts

| Valley | District | Area (km2) | Population (1998) | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khaplu | Ghanche | 9,400 | 88,366 | Khaplu |

| Skardu | Skardu | 18,000 | 219,209 | Skardu |

| Shigar | Shigar | 6,450 | 60,295 | Center Shigar |

| Kharmang | Kharmang | 5,520 | 62,522 | Tolti |

| Roundu | Skardu | 80,000 | Thowar | |

| Gultari | Skardu | |||

| Shyok° | Leh, India | 4,000 (2011) | Turtuk |

°Although under Indian control since 1971, geographically, the Turtuk part of Shyok Valley, is part of Baltistan region.

History

For centuries, Baltistan consisted of small, independent valley states connected by the blood relationships of its rulers (rajas), trade, common beliefs and cultural and linguistic bonds.[12] The states were subjugated by the Dogra rulers of Kashmir during the 19th century.[13] On 29 August 2009 the government of Pakistan announced the creation of Gilgit–Baltistan, a provincial autonomous region with Gilgit as its capital and Skardu its largest city.

Baltistan was known as Little Tibet, and the name was extended to include Ladakh.[8] Ladakh later became known as Great Tibet. Locally, Baltistan is known as Baltiyul and Ladakh and Baltistan are known as Maryul ("red country").[14]

Origins

Tibetan Khampa entered in Khaplu through Chorbat Valley and Dardic tribes came to Baltistan through Roundu Valley from Gilgit prior to civilization, and these groups eventually settled down, creating the Balti people.[15]

Today, the people of Kharmang and Western Khaplu have Tibetan features and those in Skardu, Shigar and the eastern villages of Khaplu are Dards.[16] It was believed that the Balti people were in the sphere of influence of Zhangzhung. Baltistan was controlled by the Tibetan king in 686. Culturally influenced by Tibet, the Bon and animist Baltis began to adopt Tibetan Buddhism. Religious artifacts such as gompas and stupas were built, and lamas played an important role in Balti life.[17] [18][19] During the 14th century, Muslim scholars from Kashmir crossed Baltistan's mountainous terrain to spread Islam.[20] The Noorbakshia Sufi order further propagated the faith in Baltistan and Islam became dominant by the end of the 17th century. With the passage of time a large number also converted to Shia Islam and a few converted to Sunni Islam.[21]

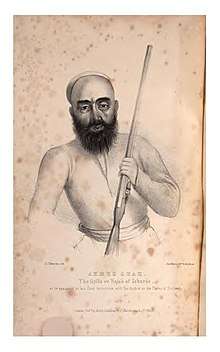

The Kharmang came under the control of the Namgyal royal family and developed a close relationship with Ladakh when the raja of Ladakh, Jamyang Mangyal, attacked the principalities in Kargil. Mangyal annihilated the Skardu garrison at Kharbu and put to the sword a number of petty Muslim rulers in the principalities of Purik (Kargil). Ali Sher Khan Anchan, raja of Khaplu and Shigar, left with a strong army via Marol. Passing the Laddakhi army, he occupied Leh (the capital of Ladakh) and the raja of Ladakh was taken prisoner.[22][23][24]

Ali Sher Khan Anchan included Gilgit and Chitral in his kingdom of Baltistan,[25] reportedly a flourishing country. The valley from Khepchne to Kachura was flat and fertile, with abundant fruit trees; the sandy desert now extending from Sundus to Skardu Airport was a prosperous town. Skardu had hardly recovered from the shock of the death of Anchan when it was flooded. In 1845, the area was seized by the Dogras.[26]

Tourism

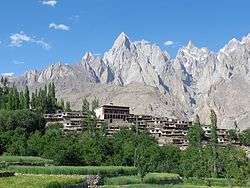

Skardu has several tourist resorts and many natural features, including plains, mountains and mountain-valley lakes. The Deosai plain, Satpara Lake and Basho also host tourists. North of Skardu, the Shigar Valley offers plains, hiking tracks, peaks and campsites. Other valleys in Baltistan region are Khaplu, Rondu, Kachura Lake and Kharmang.

Glaciers

Baltistan is a rocky wilderness of around 70,000 square kilometres (27,000 sq mi),[27] with the largest cluster of mountains in the world and the biggest glaciers outside the polar regions. The Himalayas advance into this region from India, Tibet and Nepal, and north of them are the Karakoram range. Both ranges run northwest, separated by the Indus River. Along the Indus and its tributaries are many valleys. Glaciers include Baltoro Glacier, Biafo Glacier, Siachen Glacier, Trango Glacier and Godwin-Austen Glacier.

Mountaineering

Baltistan is home to more than 20 peaks of over 6,100 metres (20,000 ft), including K2 (the second-highest mountain on earth.[17] Other well-known peaks include Masherbrum (also known as K1), Broad Peak, Hidden Peak, Gasherbrum II, Gasherbrum IV and Chogolisa (in the Khaplu Valley). The following peaks have been scaled:

| Name | Height | Date climbed | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K2 |  | 8,610 m (28,250 ft) | 31 July 1954 | Shigar District |

| Gasherbrum I |  | 8,030 m (26,360 ft) | 7 July 1956 | Ghanche District |

| Broad Peak |  | 8,090 m (26,550 ft) | 9 June 1957 | Ghanche District |

| Muztagh Tower |  | 7,300 m (23,800 ft) | 6 August 1956 | Ghanche District |

| Gasherbrum II |  | 7,960 m (26,120 ft) | 4 July 1958 | Ghanche District |

| Hidden Peak |  | 8,070 m (26,470 ft) | 4 July 1957 | Ghanche District |

| Khunyang Chhish | 7,852 m (25,761 ft) | 4 July 1971 | Skardu District | |

| Masherbrum |  | 7,821 m (25,659 ft) | 4 August 1960 | Ghanche District |

| Saltoro Kangri |  | 7,700 m (25,400 ft) | 4 June 1962 | Ghanche District |

| Chogolisa |  | 7,665 m (25,148 ft) | 4 August 1963 | Ghanche District |

Demographics

The region has a population of about 322,000. It is a blend of ethnic groups, predominantly Baltis,[28] Tibetans, and Monpas. A few Kashmiris settled in Skardu, practicing agriculture and woodcraft.

Religion

Before the arrival of Islam, Tibetan Buddhism and Bön (to a lesser extent) were the main religions in Baltistan. Buddhism can be traced back to before the formation of the Tibetan Empire in the region during the seventh century. The region has a number of surviving Buddhist archaeological sites. These include the Manthal Buddha Rock, a rock relief of the Buddha at the edge of the village (near Skardu) and the Sacred Rock of Hunza. Nearby are former sites of Buddhist shelters.

Islam was brought to Baltistan by Sufi missionaries during the 16th and 17th centuries, and most of the population converted to Noorbakshia Islam. The scholars were followers of the Kubrawiya Sufi order.[29] Most Noorbakhshi Muslims live in Ghanche and Shigar districts, and 30 percent live in the Skardu district.[30]

Fauna

Baltistan has been called a living museum for wildlife.[31] Deosai National Park, in the southern part of the region, is habitat for predators since it has an abundant prey population. Domestic animals include yaks (including hybrid yaks), cattle, sheep, goats, horses and donkeys. Wild animals include ibex, markhor, musk deer, snow leopards, brown and black bears, jackals, foxes, wolves and marmots.

Culture

Balti music and art

According to Balti folklore, Mughal princess Gul Khatoon (known in Baltistan as Mindoq Gialmo—Flower Queen) brought musicians and artisans with her into the region and they propagated Mughal music and art under her patronage.[32] Musical instruments such as the surnai, karnai, dhol and chang were introduced into Baltistan.

Dance

Classical and other dances are classified as sword dances, broqchhos and Yakkha and ghazal dances.[33] Chhogho Prasul commemorates a victory by the Maqpon rajas. As a mark of respect, the musician who plays the drum (dang) plays for a long time. A Maqpon princess would occasionally dance to this tune. Gasho-Pa, also known as Ghbus-La-Khorba, is a sword dance associated with the Gasho Dynasty of Purik (Kargil). Sneopa, the marriage-procession dance by pachones (twelve wazirs who accompany the bride), is performed at the marriage of a raja.

Architecture

Balti architecture has Tibetan and Mughul[34] influences, and its monastic architecture reflects the Buddhist imprint left on the region. Buddhist-style wall paintings can be seen in forts and Noorbakhshi khanqahs, including Chaqchan Mosque in Khaplu, Amburik Mosque in Shigar, Khanqah e Muallah Shigar, Khaplu Fort, Shigar Fort and Skardu Fort.

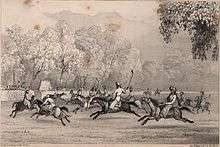

Polo

Polo is popular in Baltistan, and indigenous to the Karakoram region, having been played there since at least the 15th–16th century.[35] The Maqpon ruler Ali Sher Khan Anchan introduced the game to other valleys during his conquests beyond Gilgit and Chitral.[36] The English word polo derives from the Balti word polo, meaning "the ball used in the game of polo".[37] The game of polo itself is called shagran in Balti.[38]

Media

The Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation[39] has radio and television stations in Khaplu that broadcast local programs, and there are a handful of private news outlets. The Daily K2[40] is an Urdu newspaper published in Skardu serving Gilgit-Baltistan for long time, and it is the pioneer of print media in Gilgit Baltisatn. Bad-e-Shimal claims the largest daily circulation in Gilgit and Baltistan.[41] Nawa-e-Sufia is a monthly magazine covering Baltistan's Nurbakshi sect.[42]

See also

Notes

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, p. 8, ISBN 1860648983

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, p. 30, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Proceedings - Punjab History Conference. Punjabi University. 1968.

- Kaul, H. N. (1998), Rediscovery of Ladakh, Indus Publishing, p. 88, ISBN 978-81-7387-086-6

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, pp. 65–66, ISBN 1860648983

- Atul Aneja, A 'battle' in the snowy heights, The Hindu, 11 January 2001.

- "In pictures: Life in Baltistan". bbc.com. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dani 1998, p. 219.

- Pirumshoev & Dani 2003, p. 243.

- Karim 2009, p. 62.

- "A Socio-Political Study of Gilgit Baltistan Province" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gertel, Jörg; Richard Le Heron (2011). Economic Spaces of Pastoral Production and Commodity Systems. Ashgate. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-4094-2531-1.

- Yousaf Hussain Abadi, A view on Baltistan

- Tarar, Mustansar Hussain (1991), Nanga Parbat (in Urdu)

- Where Indus is Young

- Afridi, Banat Gul (1988). Baltistan in history. Peshawar, Pakistan: Emjay Books International.

- Tarekh e jammu, molvi hashmatullah

- Hussainabadi, Muhammad Yousuf: Baltistan per Aik Nazar 1984

- "Baltistan - North Pakistan". Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- "Little Tibet: Renaissance and Resistance in Baltistan". Himal Southasian. 30 April 1998. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Hussainabadi, Muhammad Yousuf: Tareekh-e-Baltistan 2003

- Tikoo, Tej K. (2012). Kashmir: Its Aborigines and Their Exodus. Lancer International Incorporated. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-935501-34-3.

- Stobdan, P.; Chandran, D. Suba (April 2008). The last colony: Muzaffarabad-Gilgit-Baltistan. India Research Press with Centre for Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu.

- Ramble, Charles; Brauen, Martin (1993). Proceedings of the International Seminar on the Anthropology of Tibet and the Himalaya: September 21-28 1990 at the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich. Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich. ISBN 978-3-909105-24-3.

- Ali, Manzoom (12 June 2004). Archaeology of Dardistan.

- "ABOUT GILGIT-BALTISTAN". Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Hussain, Ejaz. "Geography and Dempgraphy of Gilgit Baltistan (GB Scouts)". www.gilgitbaltistanscouts.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "NYF".

- "Sofia Imamia Noorbakhshia". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- "Beautiful Gilgit Baltistan". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- "BALTI MUSIC AND ART".

- Hussainabadi, Muhammad Yousuf: Balti Zaban 1990

- Wallace, Paul (1996) . A History of Western Himalayas . Penguin Books, London.

- Malcolm D. Whitman, Tennis: Origins and Mysteries, Published by Courier Dover Publications, 2004, ISBN 0-486-43357-9, p. 98.

- Dani, Ahmad Hassan: History of Northern Areas of Pakistan, National Institute of Historical Research, Islamabad, 1991.

- Skeat, Walter William (1898). A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Harper. p. 629.

- Afridi, Banat Gul (1988). Baltistan in history. Peshawar, Pakistan: Emjay Books International. p. 135.

- "Radio Pakistan".

- "dailyk2".

- "Daily Bad e Shimal".

- "Nuwa-e-Sufia".

Bibliography

- Aggarwal, Ravina (2004), Beyond Lines of Control: Performance and Politics on the Disputed Borders of Ladakh, India, Duke University Press, pp. 199–, ISBN 0-8223-3414-3

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1998), "The Western Himalayan States", in M. S. Asimov; C. E. Bosworth (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV, Part 1 – The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century – The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO, pp. 215–225, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Karim, Afsir (2009), "Strategic dimensions of the trans-Himalayan frontiers", in K. Warikoo (ed.), Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives, Routledge, pp. 56–66, ISBN 978-1-134-03294-5

- Pirumshoev, H. S.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003), "The Pamirs, Badakhshan and the Trans-Pamir States", in Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib (eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. V – Development in contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, UNESCO, pp. 225–246, ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Baltistan. |