Nieuwe Zakelijkheid

Nieuwe Zakelijkheid, translated as New Objectivity or New Pragmatism, is a Dutch period of modernist architecture that started in the 1920s and continued into the 1930s. The term is also used to denote a (brief) period in art and literature (especially the early novels Blokken, Knorrende Beesten, and Bint by Ferdinand Bordewijk[1]). Related to and descended from the German movement Neue Sachlichkeit, Nieuwe Zakelijkheid is characterized by angular shapes and designs that are generally free of ornamentation and decoration. The architecture is based on functional considerations and often included open layouts that allowed spaces to be used with flexibility. Sliding doors were included in some of the designs.[2]

The movement is associated with Het Nieuwe Bouwen (new building) and was contemporary and related to cubism and De Stijl, and applies similar design principles to architecture.[3] Dutch architects working in this style included Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld, and J.J.P. Oud.[4] The architectural style is similar to the artwork of Piet Mondrian, who was working contemporaneously with the architects. Common influences are also seen in furniture designs.

Some critics associated the style with dogmatic Marxism or Capitalism, seeing in the buildings a reflection of the mass-produced values that comes with a focus on economy rather than craftsmanship.

Dutch East Indies

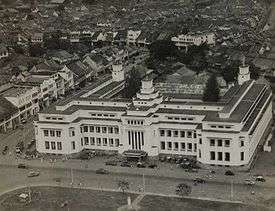

By the end of the 1920s, Nieuwe Zakelijkheid had become popular in the Dutch East Indies. The style was slightly conformed to the tropical climate of Indonesia with the addition of the 'double facade' concept, a typical element of tropical Indische architecture. The earliest example of this is the office of the Netherlands Trading Society building (1929) in Batavia, Dutch East Indies now Bank Mandiri Museum, built under a well-planned spatial planning around the station square Stationsplein of Kota Station, a sample of pre-World War II urban planning which for Southeast Asia was completely unprecedented. Other notable examples are Palembang City Hall (Snuyf, 1928-1931, nicknamed Gedung Ledeng, Indonesian "plumb building") and Kota Post Office Building (Baumgartner, 1929).[5]

See also

References

- There continues to be disagreement as to whether Bordewijk really "belonged" to that style. See Ralf Grüttemeier, "Bordewijk en de Nieuwe Zakelijkheid," in "Ralf Grüttemeier, 'Bordewijk en de Nieuwe Zakelijkheid' · DBNL". Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse taal- en letterkunde. 115: 334–55. 1999. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- D. J. M. van der Voordt, Herman B. R. Wegen Architecture in Use page 56

- Dennis Sharp The Illustrated encyclopedia of architects and architecture 1991

- Van Der Voordt, D. J. M; Wegen, Herman B. R (2005). Architecture in use: An introduction to the programming, design and evaluation of buildings. ISBN 978-0-7506-6457-8.

- Het Indische bouwen: architectuur en stedebouw in Indonesie : Dutch and Indisch architecture 1800-1950. Helmond: Gemeentemuseum Helmond. 1990. pp. 28–31. Retrieved March 30, 2015.