Hormizd IV

Hormizd IV (also spelled Hormozd IV or Ohrmazd IV; Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭬𐭦𐭣; New Persian: هرمز چهارم) was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 579 to 590. He was the son and successor of Khosrow I (r. 531–579) and his mother was a Khazar princess.

| Hormizd IV 𐭠𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭬𐭦𐭣 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iran and Aniran | |

Coin of Hormizd IV, minted at Spahan. | |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| Reign | 579–590 |

| Predecessor | Khosrow I |

| Successor | Bahram Chobin (rival king) Khosrow II (successor) |

| Born | c. 540 |

| Died | 590 (aged 49–50) Ctesiphon |

| Spouse | See below |

| Issue | See below |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Khosrow I |

| Mother | Khazar princess |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

During his reign, Hormizd IV had the high aristocracy and Zoroastrian priesthood slaughtered, whilst supporting the landed gentry (the dehqan). His reign was marked by constant warfare: to the west, he fought a long and indecisive war with the Byzantine Empire, which had been ongoing since the reign of his father; and to the east, the Iranian general Bahram Chobin successfully contained and defeated the Western Turkic Khaganate during the First Perso-Turkic War. Jealous of Bahram's success, Hormizd IV had him disgraced and dismissed, which led to a rebellion led by Bahram, which marked the start of the Sasanian civil war of 589-591. Another faction, led by two other dissatisfied nobles, Vistahm and Vinduyih, had Hormizd IV deposed and killed, and elevated his son Khosrow II as the new king (shah).

Hormizd IV was noted for his religious tolerance, declining appeals by the Zoroastrian priesthood to persecute the Christian population of the country. Contemporary sources generally considered him to be a tyrannical figure, due to his policies. Modern historiography presents a milder view of him, and considers him a well-meaning ruler who strived to continue his father's policies, albeit overambitiously.

Etymology

Hormizd (also spelled Ōhrmazd, Hormozd) is the Middle Persian version of the name of the supreme deity in Zoroastrianism, known in Avestan as Ahura Mazda.[1] The Old Persian equivalent is Auramazdā, while the Greek transliteration is Hormisdas.[1][2]

Ancestry

Hormizd was the son of Khosrow I, one of the most celebrated of the Sasanian shahs. Oriental sources and modern scholars have associated Hormizd's maternal grandfather with Istemi, the khagan of the Turks, who allied himself with Khosrow I in c. 560 to put an end to the Hephthalites, which the two allied powers accomplished at the Battle of Gol-Zarriun.[3] Khosrow I was given the daughter of Istemi in marriage, who reportedly gave birth to Hormizd.[4] Hormizd is thus called a Torkzad(a) in the Shahnameh, or 'son of a Turk'.[4] This is, however, rejected by the Iranologist Shapur Shahbazi, who called such a relationship a "chronological difficulty", due to sources mentioning Hormizd being sent by his father to contain the threat posed by Istemi, following the division of Hephthalite territory between the Sasanians and Turks.[4]

Historians consider it more plausible that Hormizd was born around 540: his son Khosrow II was thus born in c. 570.[4][5] The 7th-century Armenian historian Sebeos called Hormizd's mother a "daughter of the khagan of the Turks" and referred to her as Kayen, whilst Mas'udi called her Faqom, stating that she was the daughter of the ruler of the Khazars.[4] Shahbazi supported the German orientalist Josef Markwart in his deduction that Hormizd's maternal grandfather was the khagan of the Khazars (who are frequently called Turks in other sources),[4] and that Sebeos had referred to Hormizd's mother by her father's name (or title).[4] The medieval Iranian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh also mentioned Khosrow I and the Khazar king organizing to marry each other's daughters.[4] Hormizd was thus not only an offspring of the highly esteemed Khosrow I of the ruling family of Iran, but also belonged to a royal Turkic dynasty, which according to Sebeos "made Hormizd even greater than his paternal ancestors and equally greater and wilder than his maternal relatives".[4]

Policies and personality

%22%2C_Folio_from_a_Shahnama_(Book_of_Kings)_MET_DP215844.jpg)

Khosrow I, aware that Hormizd had showed himself as a leader of quality, appointed Hormizd as his heir.[4] The decision was also politically motivated, due to Hormizd's maternal line being of noble lineage, whilst the mothers of Khosrow I's other sons were more lowly.[4] Hormizd came to the throne in 579: according to the narratives included in the history of al-Tabari, Hormizd was well learned and full of good aspirations of kindness toward the poor and weak.[6] Hormizd appears to have strived his best to continue the policies of his father—supporting the landed gentry (the dehqan) against the aristocracy and protecting the rights of the lower classes, as well as thwarting efforts by the Zoroastrian priesthood to reassert themselves.[7] He did, however, resort to executions in order to maintain his father's policies, and as a result became the subject of hostility by the Zoroastrians.[7] He declined an appeal by the priesthood to persecute the Christian population by asserting his wish that "all his subjects were to exercise their religion freely".[4] He reportedly had many members of the priesthood killed, including the chief priest (mowbed) himself.[4]

He strained his relationship with the aristocracy by having thousands of them killed.[4] Many had been distinguished figures under Hormizd's father, such as the latter's famous minister (wuzurg framadar) Bozorgmehr; the military commander (spahbed) of Khwarasan, Chihr-Burzen; the spahbed of Nemroz, Bahram-i Mah Adhar; the distinguished dignitary Izadgushasp; the spahbed of the southwest (Khwarwaran), Shapur, an Ispahbudhan nobleman who was the father of Vistahm; Vinduyih; and an unnamed daughter whom Hormizd had married.[8][9] Hormizd was himself related to the family, with his paternal grandmother being a sister of Bawi, the father of Shapur.[10] Hormizd was not the first Sasanian shah to kill a close relative from the Ispahbudhan family: his father Khosrow I had ordered the execution of Bawi in the early 530s.[11] Nevertheless, the Ispahbudhans continued to enjoy such a high status that they were acknowledged as "kin and partners of the Sasanians", with Vistahm being appointed as the successor of his father by Hormizd.[9][8]

Due to his persecutions against the nobility and clergy, Hormizd thus became viewed with hostility in Persian sources.[4][12] This was not unusual: the 5th-century Sasanian ruler Yazdegerd I is portrayed very negatively in Persian sources due to his tolerant policy towards his non-Zoroastrian subjects, and his refusal to comply with the demands of the aristocracy and priesthood, thus becoming known as the "sinner".[13] Although met with hostility in medieval sources, Hormizd is portrayed in a more positive light in modern sources. The German orientalist Theodor Nöldeke deemed the negative portrayal of Hormizd as unreasonable, and considered the shah to be "a well-meaning sovereign who intended to restrain the nobility and clergy and ease the burden of the lower classes: his effort was on the whole justified, but the unhappy outcome shows that he was not the man to reach such lofty goals with peace and competence".[4]

War against the Byzantines

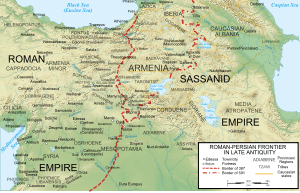

From his father, Hormizd had inherited an ongoing war against the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Negotiations of peace had just begun with the Emperor Tiberius II, who offered to give up all claims to Armenia and interchange the Byzantine-occupied Arzenere for the Iranian-occupied Dara (which was an important Byzantine stronghold).[4][14] Hormizd, however, further demanded the payment of the yearly tribute that was made during the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), and thus caused the negotiations to be broken off.[15] No campaign in Mesopotamia was undertaken by either of the empires due to the negotiations, however they continued to clash in Armenia, where Varaz Vzur succeeded Tamkhosrow as the new Sasanian governor of Armenia.[16]

The Byzantines were successful at their endeavors, securing a noteworthy victory under the commanders Cours and John Mystacon, albeit also suffering a defeat at the hands of the Sasanians.[16] In early 580, the clients and vassals of the Sasanians, the Lakhmids, were defeated at the hands of the Ghassanids, vassals of the Byzantines.[16] In the same year, a Byzantine army ravaged Garamig ud Nodardashiragan, reaching as far as Media.[17][4] Around the same time, Hormizd appointed Khosrow as the governor of Caucasian Albania, who negotiated with the Iberian aristocracy and won their support, so successfully bringing Iberia back under Sasanian rule.[17][5]

The following year, an ambitious campaign by the Byzantine commander Maurice, supported by Ghassanid forces under al-Mundhir III, targeted the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon. The combined force moved south along the river Euphrates, accompanied by a fleet of ships. The army stormed the fortress of Anatha and moved on until it reached the region of Beth Aramaye in central Mesopotamia, near Ctesiphon. There they found the bridge over the Euphrates destroyed by the Iranians.[18][19] In response to Maurice's advance, the Iranian general Adarmahan was ordered to operate in northern Mesopotamia, threatening the Byzantine army's supply line.[20] Adarmahan raided Osrhoene, and was successful in capturing its capital, Edessa.[21] He then marched his army toward Callinicum on the Euphrates. With the possibility of a march to Ctesiphon gone, Maurice was forced to retreat. The retreat was arduous for the tired army, and Maurice and al-Mundhir exchanged recriminations for the expedition's failure. However, they cooperated in forcing Adarmahan to withdraw, and defeated him at Callinicum.[22]

Tiberius tried afterwards to renew negotiations by sending Zachariah to the frontier to meet Andigan.[23] The negotiations broke off once more after Andigan attempted to pressurize him by drawing the attention of the nearby Iranian contingent led by Tamkhosrow.[23] In 582, Tamkhosrow, along with Adarmahan, invaded Byzantine territory and headed for the town of Constantina. Maurice, who had been expecting and preparing for such an attack, fought the Iranians outside the city in June 582. The Iranian army suffered a heavy defeat, and Tamkhosrow was killed.[24][23] Not long afterwards, the deteriorating physical condition of Tiberius forced Maurice to return immediately to Constantinople to assume the crown.[4] Meanwhile, John Mystacon, who had replaced Maurice as the commander of the east, attacked the Sasanians at the junction of the Nymphius and the Tigris, but was defeated and forced to withdraw.[25] He was shortly replaced by Philippicus.[25] The war continued inconclusively through raids and counter-raids, punctuated by abortive peace talks—the one significant clash was a Byzantine victory at the Battle of Solachon in 586.[26] The war ultimately achieved very little for either side.[4]

Turkic incursions in the east

.jpg)

In 588, the Turkic Khagan Bagha Qaghan (known as Sabeh/Saba in Persian sources), together with his Hephthalite subjects, invaded the Sasanian territories south of the Oxus, where they attacked and routed the Sasanian soldiers stationed in Balkh. After conquering the city, they proceeded to take Talaqan, Badghis, and Herat.[27] In a council of war, Bahram Chobin of the Parthian Mihranid family was chosen to lead an army against them and was given the governorship of Khorasan. Bahram's army, supposedly consisting of 12,000 hand-picked horsemen,[28] ambushed a large army of Turks and Hephthalites in April 588, at the Battle of Hyrcanian Rock.[29] In 589 he retook Balkh, where he captured the Turkic treasury and the golden throne of the Khagan.[30] He then proceeded to cross the Oxus river and won a decisive victory over the Turks, personally killing Bagha Qaghan with an arrowshot.[28][31] He managed to reach as far as Baykand, near Bukhara, and also contain an attack by the son of the deceased Khagan, Birmudha, whom Bahram had captured and sent to Ctesiphon.[30]

Birmudha was well received there by Hormizd, who forty days later had him sent back to Bahram with the order that the Turkic prince should get sent back to Transoxiana.[30] The Sasanians now held suzerainty over the Sogdian cities of Chach and Samarkand, where Hormizd minted coins.[30][lower-alpha 1] After Bahram's great victory against the Turks he was sent to Caucasus to repel an invasion of nomads, possibly the Khazars, where he was victorious. He was once again made commander of the Sasanian forces against the Byzantines, and successfully defeated a Byzantine force in Georgia. However, he then suffered a minor defeat by a Byzantine army on the banks of the Aras. Hormizd, who was jealous of Bahram, used this defeat as an excuse to dismiss him from his office, and had him humiliated.[32][28]

According to one source, Bahram was the subject of jealousy by others after his victory against the Turks. Hormizd's minister Azen Gushnasp, who was reportedly jealous of Bahram, accused him of having kept the best part of the booty for himself and only sending a small part to Hormizd.[33] According to other sources, it was Birmudha or the courtiers that raised Hormizd's suspicion.[33] Regardless, Hormizd could not tolerate the rising fame of Bahram, and thus had him disgraced and removed from office for supposedly having kept some of the booty for himself. Furthermore, Hormizd sent him a chain and a spindle to show that he considered him as a lowly slave "as ungrateful as a woman".[28] Enraged, Bahram, who was still in the east, rebelled against Hormizd.[28] The version of Bahram rebelling after his defeat against the Byzantines was supported by Nöldeke in 1879. However, a source found ten years later confirmed Bahram's rebellion took in fact place while he was still in the east.[28]

Overthrow and death

Due to his noble status and great military knowledge, Bahram's soldiers and many others joined the rebellion,[28] which marked the start of the Sasanian civil war of 589-591. Bahram then appointed a new governor for Khorasan, and afterwards set for Ctesiphon.[28] The legitimacy of the House of Sasan had been established in the credence that the halo of kingship, the xwarrah, was given to the first Sasanian shah, Ardashir I (r. 224–242) and his family following the latter's conquest of the Parthian Empire.[34] This was now, however, disputed by Bahram, thus marking the first time in Sasanian history that a Parthian dynast challenged the legitimacy of the Sasanian family by rebelling.[35][34] Azen Gushnasp was sent to suppress the rebellion, but was murdered in Hamadan by Zadespras, one of his own men. Another force under Sarames the Elder was also sent to stop Bahram, who defeated him and had him trampled to death by war elephants.[36] The route taken by Bahram was presumably the northern edge of the Iranian plateau, where in 590 he had repelled a Byzantine-funded attack by Iberians and others on Adurbadagan, and suffered a minor setback by a Byzantine force employed in Transcaucasia.[5] He then marched southwards Media, where Sasanian monarchs, including Hormizd, ordinarily resided during the summer.[5]

Hormizd then left for the Great Zab in order to cut communications between Ctesiphon and the Iranian soldiers on the Byzantine border.[5] Around that time the soldiers, who were situated outside Nisibis, the chief city in northern Mesopotamia, rebelled against Hormizd and pledged their allegiance to Bahram.[5] The influence and popularity of Bahram continued to grow: Sasanian loyalist forces sent north against the Iranian rebels at Nisibis were flooded with rebel propaganda.[5] The loyalist forces eventually also rebelled and killed their commander, which made the position of Hormizd become unsustainable. He decided to navigate the Tigris river and take sanctuary in al-Hira, the capital of the Lakhmids.[5]

During Hormizd's stay at Ctesiphon, he was overthrown in a seemingly bloodless palace revolution by his brothers-in-law Vistahm and Vinduyih, who according to the Syriac writer Joshua the Stylite, both "equally hated Hormizd".[5][8] They had Hormizd blinded with a red-hot needle, and put his oldest son Khosrow II (who was their nephew through his mother's side) on the throne.[37][5] Sometime in the summer of 590, the two brothers then had Hormizd killed, with at least the implicit approval of Khosrow II.[5] Nevertheless, Bahram continued his march to Ctesiphon, now with the pretext of claiming to avenge Hormizd.[30] Hormizd's death continued to be a controversial matter—a few years later, Khosrow II ordered the execution of both his uncles as well as other nobles who had a hand in the killing of his father.[5] A few decades later, Khosrow II, after being overthrown in a coup by his son Kavad II, was accused of regicide against his father.[38]

Religious policy and beliefs

Hormizd, like all other Sasanian rulers, was an adherent of Zoroastrianism.[39] Since the 5th-century, the Sasanian monarchs had been made aware of the significance of the religious minorities in the realm, and as a result tried to homogenize them into a structure of administration where according to legal principles, all would be treated straightforwardly as mard / zan ī šahr, i.e. "man/woman citizen (of the Empire)".[40] Jews and (notably) Christians had accepted the concept of Iran and considered themselves part of the nation.[40] Hormizd, aware of the importance of the Christians and their support, refused to attack them when asked by the Zoroastrian clergy, whom he reportedly urged to acknowledge the input of the Christians.[41] According to al-Tabari's History of Prophets and Kings and the Chronicle of Seert, which both drew some of their work from the Middle Persian history book Khwaday-Namag ("Book of Lords"), Hormizd told the clergy:[42]

"Just as our royal throne cannot stand on its two front legs without the two back ones, our kingdom cannot stand or endure firmly if we cause the Christians and adherents of other faiths, who differ in belief from ourselves, to become hostile to us. So refrain from harming the Christians and become assiduous in good works, so that the Christians and the adherents of other faiths may see this, praise you for it, and feel themselves drawn toward your religion."

Hormizd was himself married to a Christian woman and prayed to the martyr St. Sergius, a military saint whose cult rapidly increased beyond political and cultural borders from the 5th to the 7th-century.[43][44] He was as a result suspected of harboring Christian beliefs.[43] However, his son Khosrow II also paid tribute to Sergius, more than once.[5][44] Hormizd superstitiously wore a talisman against death, and stressed the importance of astrology.[43]

Family

Two of Hormizd's wives are known, one of them being an Ispahbudhan noblewoman, who was the daughter of Bawi,[9] whilst the other one was a Christian woman.[43]

Besides Khosrow II (r. 590–628), Hormizd also had an unnamed daughter, who married Shahrbaraz of the House of Mihran.[45]

Notes

- The Sasanians only managed to retain Chach and Samarkand for a few years, until it was re-captured by the Turks, who seemingly also conquered the eastern Sasanian province of Kadagistan.[30]

References

- Shayegan 2004, pp. 462–464.

- Vevaina & Canepa 2018, p. 1110.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 141.

- Shahbazi 2004, pp. 466–467.

- Howard-Johnston 2010.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 295.

- Axworthy 2008, p. 63.

- Shahbazi 1989, pp. 180–182.

- Pourshariati 2008, pp. 106–108.

- Pourshariati 2008, pp. 110–111.

- Pourshariati 2008, pp. 112, 268–269.

- Kia 2016, pp. 249–250.

- Kia 2016, pp. 282–283.

- Kia 2016, p. 249.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 160–162.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 162.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 163.

- Shahîd 1995, pp. 413–419.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 163–165.

- Shahîd 1995, p. 414.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 164.

- Shahîd 1995, p. 416; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 165.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 166.

- Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 1215–1216.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 167.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 167–169; Whitby & Whitby 1986, pp. 44–49.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 177.

- Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514–522.

- Jaques 2007, p. 463.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 178.

- Litvinsky & Dani 1996, pp. 368–369.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 172.

- Tafazzoli 1988, p. 260.

- Shayegan 2017, p. 810.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 96.

- Warren, p. 26.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 49.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 155.

- Payne 2015, p. 2.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 56.

- Payne 2015, p. 167.

- Payne 2015, pp. 166–167.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 337.

- Payne 2015, p. 172.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 205.

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Axworthy, Michael (2008). A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind. New York: Basic Books. pp. 1–368. ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard-Johnston, James (2010). "Ḵosrow II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 27 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1–1354. ISBN 9780313335389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Litvinsky, B. A.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. III. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231032110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Payne, Richard E. (2015). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. pp. 1–320. ISBN 9780520961531.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran (PDF). London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (registration required)

- Shahbazi, A. Sh. (1988). "Bahrām VI Čōbīn". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. London et al. pp. 514–522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1989). "Besṭām o Bendōy". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 2. pp. 180–182.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozd IV". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 466–467.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2004). "Hormozd I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 462–464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2017). "Sasanian political ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–1021. ISBN 9780190668662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tafazzoli, A. (1988). "Āẕīn Jošnas". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 3. p. 260.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vevaina, Yuhan; Canepa, Matthew (2018). "Ohrmazd". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warren, Soward. Theophylact Simocatta and the Persians. Sasanika.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitby, Michael; Whitby, Mary (1986). The History of Theophylact Simocatta. Oxford, United Kingdom: Claredon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822799-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781848846128.

- Foss, Clive (1975). The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity. The English Historical Review. 90. Oxford University Press. pp. 721–47. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721. (subscription required)

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

- Oman, Charles (1893). Europe, 476-918, Volume 1. Macmillan.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. London and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–558. ISBN 9780199330799.

- Rawlinson, George (2004). The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 9781593331719.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

Hormizd IV | ||

| Preceded by Khosrow I |

King of kings of Iran and Aniran 579–590 |

Succeeded by Bahram Chobin (rival king) Khosrow II (successor) |