Atakapa

The Atakapa /əˈtɑːkəpə/[1] are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, who spoke the Atakapa language and historically lived along the Gulf of Mexico. The competing Choctaw people used this term for this people, and European settlers adopted the term from them. The Atakapan people were made up of several bands. They called themselves the Ishak in their own language, pronounced "ee-SHAK", which translates as "The People."[2] Within the tribe there were two moieties, and the Ishak identified as "The Sunrise People" or "The Sunset People".[3][4] Although the people were decimated by infectious disease after European contact and declined as a tribe, survivors joined other tribes. Their descendants still live in the traditional territory of southern Louisiana and Texas. People identifying as Atakapa-Ishak had a gathering in 2006.

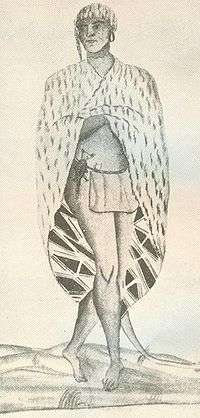

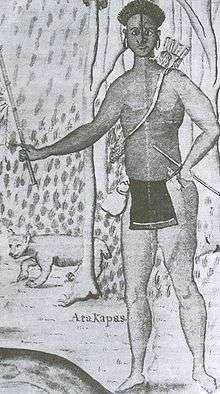

An Attakapas, by Alexandre De Batz, 1735 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 450 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

( | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Spanish, historically Atakapa | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, historically traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| isolate language group, intermarried with Caddo and Koasati |

Their name was also spelled Attakapa, Attakapas, or Attacapa. The Choctaw used this term, meaning "man eater", for their practice of ritual cannibalism. Europeans encountered the Choctaw first during their exploration, and adopted their name for this people to the west.[5][6] The peoples lived in river valleys, along lake shores, and coasts from present-day Vermilion Bay, Louisiana to Galveston Bay, Texas.[1]

After 1762, when Louisiana was transferred to Spain following French defeat in the Seven Years' War, little was written about the Atakapa as a tribe. Due to a high rate of deaths from infectious disease epidemics of the late 18th century, they ceased to function as a tribe. Survivors generally joined the Caddo, Koasati, and other surrounding tribes, although they kept some traditions. Some culturally distinct Atakapan descendants survived into the 20th century.[7]

Subdivisions or bands

Atakapa-speaking peoples are called Atakapan, while Atakapa refers to a specific tribe.[8] Atakapa-speaking peoples were divided into bands which were represented by totems, such as snake, alligator, and other natural life.

Eastern Atakapa

The Eastern Atakapa (Hiyekiti Ishak, "Sunrise People") groups live in present-day Acadiana parishes in southwestern Louisiana and are organized as three major regional bands:

- The Ciwāt or Alligator Band[9] lived along the Vermilion River and near Vermilion Bay in southwestern Iberia Parish and southeastern Vermilion Parish in south central Louisiana. This inlet of the Gulf of Mexico is separated from it by Marsh Island; they also occupied a portion of the Louisiana mainland in southeastern Vermilion Parish. The alligator was very important to this band. In addition to consuming its meat as food, they used its oil for cooking and to treat minor arthritis and eczema symptoms. They used its scales as arrowheads.

- The Otse, Teche Band, or Snake Band lived on the prairies and coastal marshes in the Mermentau River watershed, along the Bayou Nezpique, Bayou des Cannes, and Bayou Plaquemine Brule, containing the freshwater Grand and White lakes,[1] and around St. Martinville on Bayou Teche in present-day St. Martin, Lafayette, St. Landry, St. Mary, Acadia and Evangeline parishes in southern Louisiana.[10] They are named for the snake, which symbolizes the winding and twisting course of Bayou Teche.

- The Tsikip, Appalousa (Opelousa),[11] Opelousas Band ("Blackleg") or Heron Band, painted their lower legs and feet black during mourning ceremonies, mimicking the long black legs of the heron. Before European contact in the 18th century, they lived between the Atchafalaya River and Sabine River (at the present-day border of Texas-Louisiana) to the west of the lower Mississippi River. Later they were centered in the area around present-day Opelousas, Louisiana and the prairies around St. Landry Parish. They were at times associated with the neighboring Eastern Atakapa and Chitimacha peoples. They were warlike and preyed on neighbors to defend their own territory. In 1760 Chief Kinemo of the Eastern Atakapa sold the tribal lands between the Vermilion River and Bayou Teche to Frenchman Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire; the angry Appalousa exterminated the Eastern Atakapa bands for selling off communal lands. The Opelousa Band reportedly spoke the Eastern Atakapan dialect.

Western Atakapa

The Western Atakapa (Hikike Ishak, "Sunset People") reside in southeastern Texas. They are organized as follows.

- Atakapa (proper) groups, divided into major regional bands:

- The Katkoc or Eagle Band (named after the eagles in the area), were also known as Calcasieu Band, because they were living along Calcasieu River between the Calcasieu Lake in southwest Louisiana and Sabine Lake on the Louisiana-Texas border.

- The Red Bird Band, living on the prairies and coastal areasof what is now Cameron Parish, in South Western Louisiana; they were represented by the cardinal or red bird.

- The Niāl or Panther Band, living in the areas around the Sabine River of South East Texas, they took the panther as their totem.[12]

- The Akokisa, Arkokisa, or Orcoquiza ("river people"), westernmost Atakapa tribe, lived in the mid-18th century in five villages along the lower course of the Trinity and San Jacinto rivers and the northern and eastern shores of Galveston Bay in present-day Texas. In 1805, their surviving people were reported to be living in villages on the lower Colorado and Neches rivers.[13][14]

- The Quasmigdo, better known as Bidai (a Caddo language name meaning "brushwood"),[15] were based around Bedias Creek, ranging from the Brazos River to Neches River, Texas.[1]

- The Deadose, a band of Bidai that separated in the early 18th century, lived north of the other Bidai between the confluence of the Angelina River and Neches River and the upper end of Galveston Bay in east-central Texas. Around 1720 they moved westward between the Brazos and Trinity rivers; later they settled near missions on the San Gabriel River (with the Bidai and Akokisa) in the Texas Hill Country. Between 1749 and 1751 they gathered (with the Akokisa, Orcoquiza, Bidai, and Patiri) at the short-lived San Ildefonso Mission near the mouth of Brushy Creek; some settled near the Alamo Mission in San Antonio.[1] In the second half of the 18th century, the Deadose were closely associated with Tonkawan groups (Ervipiame (?), Mayeye, and Yojuane). Suffering high mortality from epidemics of measles and smallpox, survivors joined kindred Bidai, Akokisa and Tonkawa. They lost their distinctive tribal identity in the latter part of the 18th century.[16]

- The Patiri, Petaros, or Pastia lived north of the San Jacinto River valley between the Bidai to the north and the Akokisa in the south of Texas. This places them in the Piney Woods of East Texas, west of the Trinity River in the area between Houston and Huntsville. Little is known about them; perhaps they were a southern Bidai band.[1]

- The Tlacopsel, Acopsel, or Lacopspel — it is believed that they lived in the same general area as the kindred Bidai and Deadose. The location of their settlements in southeast Texas are unknown. They are known only from Spanish documents of the eighteenth century, when they were referred to for requesting missions from the Spanish in east central Texas.[17]

History

Atakapa oral history says that they originated from the sea. An ancestral prophet laid out the rules of conduct.[18]

The first European contact with the Atakapa may have been in 1528 by survivors of the Spanish Pánfilo de Narváez expedition. Men in Florida had made two barges, in an attempt to sail to Mexico, and these were blown ashore on the Gulf Coast. One group of survivors met the Karankawa, while the other probably landed on Galveston Island. The latter recorded meeting a group who called themselves the Han, who may have been the Akokisa.[1]

In 1703, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, the French governor of La Louisiane, sent three men to explore the Gulf Coast west of the Mississippi River. The seventh nation they encountered were the Atakapa, who captured, killed and cannibalized one member of their party.[1] In 1714 this tribe was one of 14 that were recorded as coming to Jean-Michel de Lepinay, who was acting French governor of Louisiana between 1717 and 1718,[19] while he was fortifying Dauphin Island, Alabama.[20]

The Choctaw told the French settlers about the "People of the West," who represented subdivisions or tribes. The French referred to them as les sauvages. The Choctaw used the name Atakapa, meaning "people eater" (hattak 'person', apa 'to eat'), for them.[18] It referred to their practice of ritual cannibalism related to warfare.

A French explorer, Francois Simars de Bellisle, lived among the Atakapa from 1719 to 1721.[1] He described Atakapa feasts including consumption of human flesh, which he observed firsthand.[21] The practice of cannibalism likely had a religious, ritualistic basis. French Jesuit missionaries urged the Atakapa to end this practice.

The French historian Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz lived in Louisiana from 1718 to 1734. He wrote:[22]

Along the west coast, not far from the sea, inhabit the nation called Atacapas, that is, Man-Eaters, being so called by the other nations on account of their detestable custom of eating their enemies, or such as they believe to be their enemies. In the vast country there are no other cannibals to be met with besides the Atacapas; and since the French have gone among them, they have raised in them so great a horror of that abominable practice of devouring creatures of their own species, that they have promised to leave it off: and, accordingly, for a long time past we have heard of no such barbarity among them.

— Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz

Louis LeClerc Milfort, a Frenchman who spent 20 years living with and traveling among the Muscogee (Creek), came upon the Atakapa in 1781 during his travels. He wrote:[23]

The forest we were then in was thick enough so that none of my men could be seen. I formed them into three detachments, and arranged them in such a way as to surround these savages, and to leave them no way of retreat except by the pond. I then made them all move forward, and I sent ahead a subordinate chief to ascertain what nation these savages belonged to, and what would be their intentions toward us. We were soon assured that they were Atakapas, who, as soon as they saw us, far from seeking to defend themselves, made us signs of peace and friendship. There were one hundred and eighty [180] of them of both sexes, busy, as we suspected, smoke-drying meat. As soon as my three detachments had emerged from the forest, I saw one of these savages coming straight toward me: at first sight, I recognized that he did not belong to the Atakapas nation; he addressed me politely and in an easy manner, unusual among these savages. He offered food and drink for my warriors which I accepted, while expressing to him my gratitude. Meat was served to my entire detachment; and during the time of about six hours that I remained with this man, I learned that he was a European; that he had been a Jesuit; and that having gone into Mexico, these people had chosen him as their chief. He spoke French rather well. He told me that his name was Joseph; but I did not learn from what part of Europe he came.

He informed me that the name Atakapas, which means eaters of men, had been given to this nation by the Spaniards because every time they caught one of them, they would roast him alive, but that they did not eat them; that they acted in this way toward this nation to avenge their ancestors for the torture that they made them endure when they had come to take possession of Mexico; that if some Englishmen or Frenchmen happened to be lost in this bay region, the Atakapas welcomed them with kindness, would give them hospitality; and if they did not wish to remain with them they had them taken to the Akancas, from where they could easily go to New Orleans.

He told me: "You see here about one-half of the Atakapas Nation; the other half is farther on. We are in the habit of dividing ourselves into two or three groups in order to follow the buffalo, which in the spring go back into the west, and in autumn come down into these parts; there are herds of these buffalo, which go sometimes as far as the Missouri; we kill them with arrows; our young hunters are very skilful at this hunting. You understand, moreover, that these animals are in very great numbers, and as tame as if they were raised on a farm; consequently, we are very careful never to frighten them. When they stay on a prairie or in a forest, we camp near them in order to accustom them to seeing us, and we follow all their wanderings so that they cannot get away from us. We use their meat for food and their skins for clothing. I have been living with these people for about eleven years; I am happy and satisfied here, and have not the least desire to return to Europe. I have six children whom I love a great deal, and with whom I want to end my days."

When my warriors were rested and refreshed, I took leave of Joseph and of the Atakapas, while assuring them of my desire to be able to make some returns for their friendly welcome, and I resumed my Journey.

— Louis LeClerc Milfort

In 1760, the French Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire came into the Attakapas Territory, and bought all the land between Vermilion River and Bayou Teche from the Eastern Atakapa Chief Kinemo. Shortly after that a rival Indian tribe, the Appalousa (Opelousas), coming from the area between the Atchafalaya and Sabine rivers, exterminated the Eastern Atakapa. They had occupied the area between Atchafalaya River and Bayou Nezpique (Attakapas Territory).

William Byrd Powell (1799–1867), a medical doctor and physiologist, regarded the Atakapan as cannibals. He noted that they traditionally flattened their skulls frontally and not occipitally, a practice opposite to that of neighboring tribes, such as the Natchez Nation.[24]

The Atakapa traded with the Chitimacha tribe.[25] In the early 18th century, some Atakapa married into the Houma tribe of Louisiana.[26] Members of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe joined the Atakapa tribe in the late 18th century.[27]

Culture

The Atakapan ate shellfish and fish. The women gathered bird eggs, the American lotus (Nelumbo lutea) for its roots and seeds, as well as other wild plants. The men hunted deer, bear, and bison, which provided meat, fat, and hides. The women cultivated varieties of maize. They processed the meats, bones and skins to prepare food for storage, as well as to make clothing, tent covers, tools, sewing materials, arrow cases, bridles and rigging for horses, and other necessary items for their survival.[18][28]

The men made their tools for hunting and fishing: bows and arrows, fish spears with bone-tipped points, and flint-tipped spears. They used poisons to catch fish, caught flounder by torchlight, and speared alligators in the eye. The people put alligator oil on exposed skin to repel mosquitoes. The Bidai snared game and trapped animals in cane pens. By 1719, the Atakapan had obtained horses and were hunting bison from horseback. They used dugout canoes to navigate the bayous and close to shore, but did not venture far into the ocean.[28]

In the summer, families moved to the coast. In winters, they moved inland and lived in villages of houses made of pole and thatch. The Bidai lived in bearskin tents. The homes of chiefs and medicine men were erected on earthwork mounds made by several previous cultures including the Mississippian.[18]

Today

It is believed that most Western Atakapa tribes or subdivisions were decimated by the 1850s, mainly from infectious disease and poverty. Armojean Reon, of Lake Charles, Louisiana, who lived at the start of the 20th century, was noted as a fluent Atakapa speaker.[29]

Descendants exist and have begun to organize to be recognized as a tribe. Numerous descendants today share a mixed lineage of Atakapa-Ishak and other ethnic ancestry, but they have maintained a sense of community and culture.[30]

The names of present-day towns in the region can be traced to the Ishak; they are derived both from their language and from French transliteration of the names of their prominent leaders and names of places. The town of Mermentau is a corrupted form of the local chief Nementou. Plaquemine, as in Bayou Plaquemine Brûlée and Plaquemines Parish, is derived from the Atakapa word pikamin, meaning "persimmon". Bayou Nezpiqué was named for an Atakapan who had a tattooed nose. Bayou Queue de Tortue was believed to have been named for Chief Celestine La Tortue of the Atakapas nation.[31] The name Calcasieu is a French transliteration of an Atakapa name: katkosh, for "eagle", and yok, "to cry".

On October 28, 2006, the Atakapa-Ishak Nation met for the first time in more than 100 years as "one nation". A total of 450 people represented Louisiana and Texas. Rachel Mouton, the mistress of ceremony and newly appointed Director of Publications and Communications, introduced Billy LaChapelle, who opened the afternoon with a traditional prayer in English and in Atakapa.[32]

The city of Lafayette, Louisiana is planning a series of trails, funded by the Federal Highway Administration, to be called the "Atakapa-Ishak Trail". It will consist of a bike trail connecting downtown areas along the bayous Vermilion and Teche, which are now accessible only by foot or boat.[33][34]

Current Atakapa-Ishak members have unsuccessfully petitioned Louisiana, Texas, and the United States for status as a recognized tribe.[35] A member of the tribe claiming to be trustee, monarch, and deity of the "Atakapa Indian de Creole Nation" filed a number of lawsuits in federal court claiming, among other things, that the governments of Louisiana and the United States seek to "monopolize intergalactic foreign trade." The suits were dismissed as frivolous.[36]

Atakapa language

The Atakapa language is a language isolate, once spoken along the Louisiana and East Texas coast and believed extinct since the mid-20th century.[37] John R. Swanton in 1919 proposed a Tunican language family that would include Atakapa, Tunica, and Chitimacha. Mary Haas later expanded this into the Gulf language family with the addition of the Muskogean languages. As of 2001, linguists generally do not consider these proposed families as proven.[38]

See also

- USS Atakapa (ATF-149)

- Attakapas Parish

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

Notes

- Sturtevant, 659

- Times of Acadiana.com

- Southwest Louisiana: A Treasure Revealed, by Jeanne Owens - HPN Books - p.13

- "Atkapa-Ishak Nation". Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- Swanton, John R. (January–March 1915). "Linguistic Position of the Tribes of Southern Texas and Northeastern Mexico". American Anthropologist. Blackwell Publishing. 17 (1): 17–40. doi:10.1525/aa.1915.17.1.02a00030. JSTOR 660145.

- Butler, Joseph T. (Spring 1970). "The Atakapas Indians: Cannibals of Louisiana". Louisiana History. Louisiana Historical Association. 11 (2): 167–176. JSTOR 4231120.

- Sturtevant, 660.

- "The Atakapa-Ishak Nation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- Atakapa Ishak Nation - Constitution of the Atakapa-Isak Nation of S.E. Texas and S.W. Louisiana (source for Band and Clan names)

- Bradshaw, Jim. "Iberia Parish was once part of Attakapas District" Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Advertiser, 25 November 1997 (retrieved 8 June 2009).

- The Opelousas

- Constitution of the Atakapa-Isak Nation of S.E. Texas And S.W. Louisiana - Listing of Tribes and Totems

- Campbell, Thomas N. (June 15, 2010). ""Akokisa Indians"". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Blake, Robert Bruce (June 15, 2010). ""Orcoquiza Indians"". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "The Bidai, Tribe of Intrigue. Who were they, Really?". Archived from the original on 2017-08-30. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- The Bidai Indians of Southeastern Texas

- Campbell, Thomas N. (June 15, 2010). ""Tlacopsel Indians"". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Sturtevant, 662.

- enlou.com Archived 2007-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Atakapa" Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Lutherans Online

- Newcomb, 327.

- "Attakapas", The Cajuns.com.

- Milfort, Louis Leclerc. Memoirs or A Quick Glance at my various travels and my sojourn in the Creek Nation, Chapter 15, Rootsweb Homepages.

- Powell, William Byrd. Letter to Samuel G. Morton. 12 August 1839. American Philosophical Society, L.S. 2p. 127.

- Pritzker, 374.

- Pritzker, 382.

- Pritzker, 393.

- Sturtevant, 661.

- Sturtevant, 660-61.

- timesofacadiana.com "This isn't Cajun Country", Times of Acadiana, 25 July 2007.

- thecajuns.com "Arrow points and place names are reminders of Attakapas", The Cajuns.

- Atakapa Ishak Nation SE Texas and SW Louisiana Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Issue No. 1, November 2006, at Lutherans Online.

- "Blazing a T.R.A.I.L.", The Independent

- "Atakapa-Ishak Trail" Archived 2012-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Lafayette, Louisiana website

- Besson, Eric (2014-09-02). "SE Texas' Atakapa tribe seeking federal designation". Beaumont Enterprise. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "Atakapa Indian de Creole Nation v. Louisiana, No. 19-30032 (5th Cir. 2019)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Gatschet, Albert S.; Swanton, John Reed; Smithsonian Institution (1932). A dictionary of the Atakapa language. Bureau of American Ethnology. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- Mithun, Marianne (2001). The Languages of Native North America (First paperback ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 302, 344. ISBN 0-521-23228-7.

References

- Newcomb, William Wilmon, Jr. The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0-292-78425-3.

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Nezat, Jack Claude. The Nezat and Allied Families 1630–2007. 2007. ISBN 978-0-615-15001-7.

- Pritzer, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000: 286-7. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

External links

- Tribes in Louisiana

- Handbook of Texas Online

- BP Oil Spill Threatens Future of Indigenous Communities in Louisiana – video report by Democracy Now!

- Atakapa-Ishak Nation