Ashton Avenue Bridge

The Ashton Avenue Bridge is a former road-rail bridge in Bristol, England.[1] Grade II listed,[2][3] it was constructed as part of the Bristol Harbour Railway, and now carries a guided busway and a local access cycle path.

Ashton Avenue Bridge | |

|---|---|

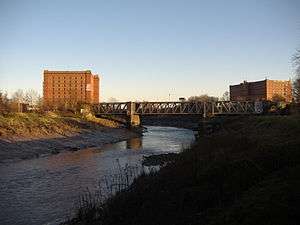

View of the New Cut across the Ashton Avenue Bridge | |

| Coordinates | 51.4461°N 2.6219°W |

| Carries | Pill Pathway rail trail |

| Crosses | River Avon at New Cut |

| Other name(s) | Ashton Swing Bridge |

| Owner | Bristol City Council |

| Characteristics | |

| Material | Iron |

| Total length | 582 feet (177 m) |

| No. of spans | 3 |

| History | |

| Designer | J.C. lnglis |

| Engineering design by | J.C. lnglis |

| Constructed by | John Lysaght and Co. |

| Fabrication by | John Lysaght Armstrong Whitworth (Hydraulics) |

| Construction start | 1905 |

| Construction end | 1906 |

| Construction cost | £70,389 |

| Opened | 3 October 1906 |

| Closed | Road: 1965 Rail: 1987 |

| |

Bristol Harbour Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a business proposal by Isambard Kingdom Brunel to shorten the travel time between London and the new world of North America, accessed via New York City. Able to gain finance from the City of Bristol, the first Act of Parliament allowed for the construction of the GWR from London to Bristol via Reading, Swindon and Bath, Somerset.

The original Bristol Harbour Railway (BHR) was a joint venture by the GWR and sister company the Bristol and Exeter Railway.[1] It opened in 1872 between Bristol Temple Meads and the Floating Harbour. Its route included a tunnel under St Mary Redcliffe church, and a steam-powered bascule bridge over the entrance locks at Bathurst Basin. In 1876 the railway was extended by .5 miles (0.80 km) west to Wapping Wharf.[1]

Construction

By Act of Parliament of 1897, the GWR was authorised to make an eastwards connection between the BHR and the Portishead Railway, and then create the West Loop at Ashton Gate which would face south towards Taunton and Exeter Central. This connection would allow a doubling of BHR rail access capacity to the Great Western main line.[4]

In 1905, it was proposed to undertake the authorised extension of the BHR from Wapping Wharf across Spike Island. It would then junction into two branches: a western branch to Wapping via a line alongside the New Cut; and to Canons Marsh on the northside of the River Avon, which would then merge with the Portishead Railway (Butterfly Junction).[2]

Under a joint agreement, Bristol Corporation and the GWR engaged as their Chief Engineer J.C. lnglis. The building contractor was John Lysaght and Co., while Armstrong Whitworth were engaged to design the hydraulic movement system.[1][2] Construction of the 582 feet (177 m) span-bridge started in 1905, with two squared rock-faced limestone piers, the southern one of which would pivot the swinging span.[2] This supported a moveable 202 feet (62 m) Whipple Murphy truss span, weighing 1,000 long tons (1,000 t), with total metal work of the entire bridge weighing in at 1,500 long tons (1,500 t).[1] With the bridge able to operate both ways, each opening/closing cycle consumed 182 imperial gallons (830 l; 219 US gal) of water from the Floating Harbour.[1][2] The bridge control cabin, road and railway signal boxes, and the reversible hydraulic motor were all housed in a single structure perched on stilts above the upper road deck.[1]

The original estimate for the bridge was £36,500, with the GWR agreeing to pay half.[2] The final cost was £70,389,[1] to which Bristol Corporation asked the GWR to increase its contribution. After further negotiation the GWR contributed £22,000.

Operations

Designed and opened as the freight-only Wapping Wharf Branch, the bridge was opened on 3 October 1906 by the Lady Mayoress, Mrs A.J.Smith. With both railway and road operations and bridge maintenance undertaken by the GWR, it opened on average ten times a day until February 1934.[1][2] The controlling railway signals were interlocked with the signal boxes on either side of the river, making it impossible for signals to be cleared unless the bridge span was locked in the closed position.[1]

Decommissioning

Bristol Corporation rescinded the GWR's obligation to maintain the swing apparatus in 1951,[1][2] after which it was welded shut. After the completion of a new A370 road dual carriageway system in the docks area, and the opening of the replacement Plimsoll Bridge to the west in 1965,[2] the road deck and signal cabin were removed.[1]

The BHR's connection with Temple Meads was closed and the track lifted in 1964, and the Canons Marsh branch closed the following year. The Western Fuel Company continued to use the line from the Portishead branch over the swing bridge and Wapping marshalling yard for commercial coal traffic.[1] The rail line over the bridge was singled in 1976, and shut operationally after Western Fuel ceased railway operations in 1987.[1][2] The bridge was revisited by GWR Pannier Tank No.1369 in 1996, prior to the re-opening of the residual BHR as a visitor attraction.[1]

Present

Grade II listed in May 2000,[2] The single track rail line remained in place over the bridge, but was highly overgrown. Network Rail later lifted the track from the bridge to Ashton Gate.[1] The other side of the railway level has been converted into rail trail foot and cycle path, part of the Pill pathway.[1] It is listed on the Heritage at Risk Register.[3]

In 2015 it was announced that the bridge would close for a period of 12 months from the autumn for a complete renovation in connection with the MetroBus project. The bridge now carries a separate single bus lane and a wider cycle and pedestrian path.[5][6]

See also

- Bristol Harbour Railway

- List of road-rail bridges

References

- Biddle, Gordon, Britain's Historic Railway Buildings, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198662475 (2003)

- Biddle, Gordon & Nock, O.S., The Railway Heritage of Britain : 150 years of railway architecture and engineering, Studio Editions, ISBN 1851705953 (1990)

- Biddle, Gordon and Simmons, J., The Oxford Companion to British Railway History, Oxford, ISBN 0 19 211697 5 (1997)

- Bonavia, Michael, Historic Railway Sites in Britain, Hale, ISBN 0 7090 3156 4 (1987)

- Conolly, W. Philip, British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas And Gazetteer, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0-7110-0320-3 (1958/97)

- Jowett, Alan, Jowett's Railway Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland, Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-8526-0086-1. (March 1989)

- John Lord and Jem Southam, The Floating Harbour, The Redcliffe Press, 1983, pps 47-8,64–5,77–8.

- E.T.MacDermot, History of the Great Western Railway, Ian Allan, revised ed. 1964,

Vol II, p 228.

- Morgan, Bryan, Railways: Civil Engineering, Arrow, ISBN 0 09 908180 6 (1973)

- Morgan, Bryan, Railway Relics, Ian Allan, ISBN 0 7110 0092 1 (1969)

- Simmons, J., The Railways of Britain, Macmillan, ISBN 0 333 40766 0 (1961–86)

- Simmons, J. The Victorian Railway, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0 500 25110X (1991)

- Smith, Martin, British Railway Bridges and Viaducts, Ian Allan, ISBN 0 7110 2273 9 (1994)

- Turnock, David, An Historical Geography of Railways, Ashgate, ISBN 1 85928 450 7 (1998)

- "Ashton Swing Bridge". Forgotten Relics. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Ashton Swing Bridge, Bristol". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Ashton Avenue Bridge". Travel West. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- E T MacDermot, The Great Western Railway, volume 2, published by the Great Western Railway, London, 1931

- "Closure of Ashton Avenue Swing Bridge". Travel West. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "First Bristol named as Metrobus operator". BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashton Avenue Bridge. |