Bathurst Basin

Bathurst Basin is a small triangular basin adjoining the main harbour of the city of Bristol, England. The basin takes its name from Charles Bathurst, who was a Bristol MP in the early 19th century.[1]

.jpg)

The basin was built on an area of an old mill pond, Trin Mills.[lower-roman 1] The pond was supplied by the River Malago, from Bedminster to the South. It lost its water supply as the New Cut was created in 1809, running to the South of the enlarged Floating Harbour and catching the flow of the Malago. After this it formed a connecting basin, through two sets of locks, between the Floating Harbour and the tidal River Avon in the New Cut.[2] The connection enabled smaller vessels to bypass the main entrance locks in Cumberland Basin. From 1865 a deep water dock with a stone quay front was built. The area used to be an industrial dock with warehouses and numerous shipyards at the adjoining Wapping Shipyard and Docks, including Hilhouse, William Scott & Sons and William Patterson. Now there is a small marina, with residential quayside properties.

The Bristol Harbour Railway connected to the main line system at Temple Meads, via a lifting bascule bridge over the northern entrance dock to the basin and a tunnel beneath St Mary Redcliffe. The tunnel still exists, but is now blocked,[lower-roman 2] and the original railway bridge has been replaced with a swing footbridge. This bridge is manually swung by a hydraulic pump action.[lower-roman 3]

Bristol General Hospital is located on the Eastern quay of the basin. When constructed in 1859, the hospital was built with basement warehouse space to defray its operating costs.[3] The Southern quay has never had any substantial buildings on it and for many years was used by Holms Sand & Gravel Co. as a depot for building materials, brought in by boat and offloaded into road vehicles. A travelling crane on an overhead gantry was used to handle these.[3][4]

1888 fire

On 21 November 1888 the Basin was the scene of a serious explosion and fire. The ketch United was laden with 310 barrels of naphtha, distilled from coal tar in Brislington, and ready for departure to London. The cargo had been loaded the previous day at Welsh Back and the Master, Henry Cartwright, was now waiting for strong winds to drop. Knowing the risk of fire for this flammable cargo, all flames had been banned from around the vessel and it had been kept in the entrance lock, not the main basin, overnight. Just after 11am, a sudden explosion rocked the basin. ‘A high wall of flame of appalling fierceness’ followed by ‘a cloud of smoke of the blackest description’, typical of burning naphtha, hurled one of the crew across the harbour to land with a broken leg. The explosion broke windows around the basin, including all those in the lower floor of the Hospital. Although rescuers boarded the Union, they were unable to rescue the trapped crew owing to the heat of the fire and three of the four crew burned to death. Liquid, burning naphtha floated across the surface of the basin and set fire to the ships there, with flames reaching masthead height. After three hours the fire burned out, aided by the efforts of horse-drawn fire engines and the docks' fire float.

Decline of the Basin

The lock to the New Cut was blocked at the beginning of World War II to ensure that in case of damage by bombing, the waters of the Floating Harbour could not drain into the river.[3] It was shut permanently in 1952.

Decline of the docks

Use for leisure

The basin is the home for Cabot Cruising Club who own the lightvessel John Sebastian, which was commissioned in 1886. It was acquired by the club in 1954 and opened as its headquarters a few years later in 1959. Facilities at the basin include a toilet and shower block, a water tap and refuse and chemical toilet disposal points.

Also in the surroundings of the basin are the Ostrich and Louisiana (originally the Bathurst Hotel) pubs.

References

- Also known as Treen, Trimm or Trim Mills

- The tunnel mouth may be seen to the right of the Ostrich

- The slowness of the manual bridge swing was a source of some local amusement when the TV hospital drama Casualty filmed an accident involving it, and a victim who couldn't escape the inexorable movement of the presumably mechanised automatic monster.

- Cork, Tristan (12 March 2017). "Forget Colston, here's five Bristol landmarks named after other slave trade businessmen". bristolpost. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Walker, F. (April 1939). "The Port of Bristol". Econ. Geogr. Taylor & Francis. 15 (2): 109–124. doi:10.2307/141420. JSTOR 141420.

- Lewis, Brian. Hotwells and the City Docks. Bygone Bristol. pp. 44–45. ISBN 1-899388-28-1.

- Fray Bentos (3 August 1975). "Death rattle of Bristol's port: Sand boat in Bathurst Basin" (photograph). 1970s photographs of lost Bristol.

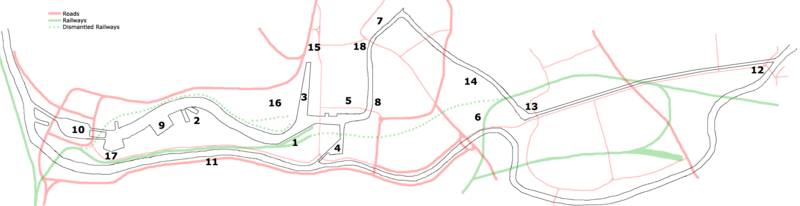

Location within Bristol harbour

- Prince's Wharf, including M Shed, Pyronaut and Mayflower adjoining Prince Street Bridge

- Dry docks: SS Great Britain, the Matthew

- St Augustine's Reach, Pero's Bridge

- Bathurst Basin

- Queen Square

- Bristol Temple Meads railway station

- Castle Park

- Redcliffe Quay and Redcliffe Caves

- Baltic Wharf marina

- Cumberland Basin & Brunel Locks

- The New Cut

- Netham Lock, entrance to the Feeder Canal

- Totterdown Basin

- Temple Quay

- The Centre

- Canons Marsh, including Millennium Square and We The Curious

- Underfall Yard

- Bristol Bridge

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bathurst Basin. |